…

Quince

Flute, you must take Thisbe on you.

Flute

What is Thisbe? a wandering knight?

Quince

It is the lady that Pyramus must love.

Flute

Nay, faith, let me not play a woman; I have a beard coming.

Quince

That’s all one: you shall play it in a mask, and

you may speak as small as you will.

Bottom

An I may hide my face, let me play Thisbe too, I’ll

speak in a monstrous little voice. ‘Thisne,

Thisne;’ ‘Ah, Pyramus, lover dear! thy Thisbe dear,

and lady dear!’

Quince

No, no; you must play Pyramus: and, Flute, you Thisbe.

Bottom

Well, proceed.

Quince

Robin Starveling, the tailor.

Starveling

Here, Peter Quince.

Quince

Robin Starveling, you must play Thisbe’s mother.

Tom Snout, the tinker.

Snout

Here, Peter Quince.

Quince

You, Pyramus’ father: myself, Thisbe’s father:

Snug, the joiner; you, the lion’s part: and, I

hope, here is a play fitted.

Snug

Have you the lion’s part written? pray you, if it

be, give it me, for I am slow of study.

Quince

You may do it extempore, for it is nothing but roaring.

Bottom

Let me play the lion too: I will roar, that I will

do any man’s heart good to hear me; I will roar,

that I will make the duke say ‘Let him roar again,

let him roar again.’

Quince

An you should do it too terribly, you would fright

the duchess and the ladies, that they would shriek;

and that were enough to hang us all.

All

That would hang us, every mother’s son.

…

(Act I Scene II)

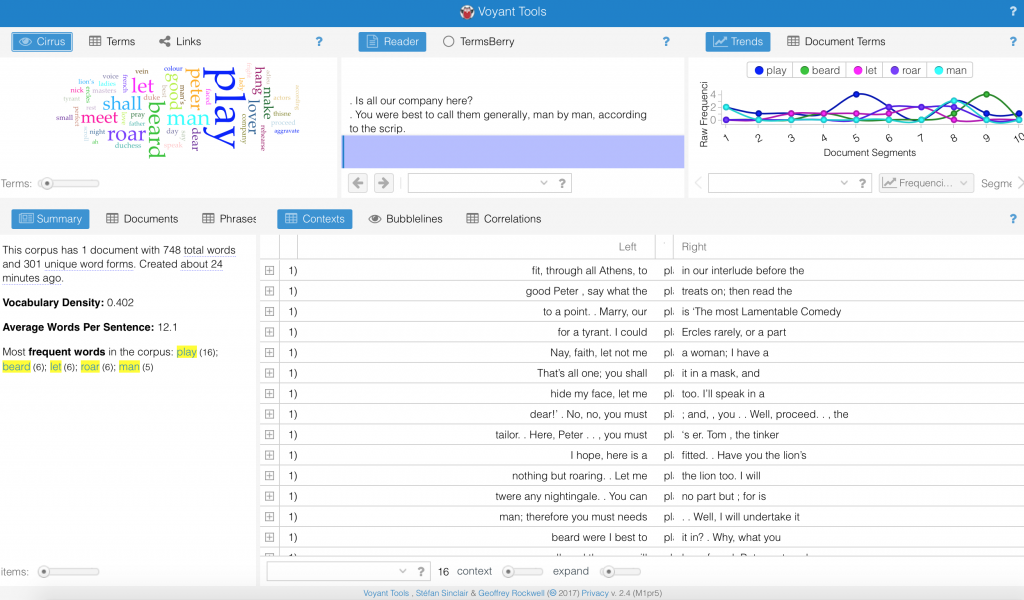

This week’s work with the digital resources proved to be quite the task (despite being the youngest person in the room, I am embarrassingly out of touch with technology). Still, using the suggested platforms proved to be very useful in pushing me to look beyond the immediacy of a small section of text and appreciate larger trends that pervade the entirety of this play. Speaking of play (!!!), I chose to focus my attention on Shakespeare’s ‘play within a play’ structure by unpacking the word’s various forms in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Voyant provided the most visually striking representation of this by mapping out the term’s sixteen occurrences in Act I Scene II (a portion of which is included above).

Though Voyant didn’t give what might be considered a sophisticated breakdown of how “play” was used in each instance (e.g. part of speech, verb tense if applicable), it was certainly helpful in emphasizing the term’s significance in relation to the surrounding text.

The role of “play,” both the idea and word itself, take on a ‘meta importance’ as the story progresses: the players, fairies, lovers, and peacemakers all, quite literally, play their part by simultaneously engaging in lighthearted acts of comedy and carefully engineered performances. Much of this is brought to the surface by the players’ production of Pyramus and Thisbe, but arguably just as much is revealed through the players’ dialogue outside of their performance. “Play” takes on multiple roles in this passage, acting as an activity for amusement (n.), the act of engaging in such activity (v.), and the process of immersing oneself in whimsical pretense (v.). It’s all very dizzying, but this is precisely what Shakespeare wants.

Taking all of this into consideration, how does the multifaceted nature of “play”—as it exists in both this specific passage and the story as a whole—shape our understanding of Snout’s line in Act III Scene I: “Doth the moon shine that night we play our play?”