ANTONY

Now, my dearest queen.

CLEOPATRA

Pray you, stand further from me.

ANTONY

What’s the matter?

CLEOPATRA

I know, by that same eye, there’s some good news.

What says the married woman? You may go:

Would she had never given you leave to come!

Let her not say ’tis I that keep you here:

I have no power upon you; hers you are.

ANTONY

The gods best know—

CLEOPATRA

O, never was there queen

So mightily betrayed! yet at the first

I saw the treasons planted.

ANTONY

Cleopatra—

CLEOPATRA

Why should I think you can be mine and true,

Though you in swearing shake the throned gods,

Who have been false to Fulvia? Riotous madness,

To be entangled with those mouth-made vows,

Which break themselves in swearing!

ANTONY

Most sweet Queen—

CLEOPATRA

Nay, pray you, seek no colour for your going,

But bid farewell, and go: when you sued staying,

Then was the time for words: no going then;

Eternity was in our lips and eyes,

Bliss in our brows’ bent; none our parts so poor,

But was a race of heaven: they are so still,

Or thou, the greatest soldier of the world,

Art turned the greatest liar.

ANTONY

How now, lady?

CLEOPATRA

I would I had thy inches, thou shouldst know

There were a heart in Egypt.

ANTONY

Hear me, Queen:

The strong necessity of time commands

Our services awhile; but my full heart

Remains in use with you. Our Italy

Shines o’er with civil swords: Sextus Pompeius

Makes his approaches to the port of Rome:

Equality of two domestic powers

Breed scrupulous faction: the hated, grown to strength,

Are newly grown to love: the condemn’d Pompey,

Rich in his father’s honour, creeps apace,

Into the hearts of such as have not thrived

Upon the present state, whose numbers threaten;

And quietness, grown sick of rest, would purge

By any desperate change: my more particular,

And that which most with you should safe my going,

Is Fulvia’s death.

CLEOPATRA

Though age from folly could not give me freedom,

It does from childishness: can Fulvia die?

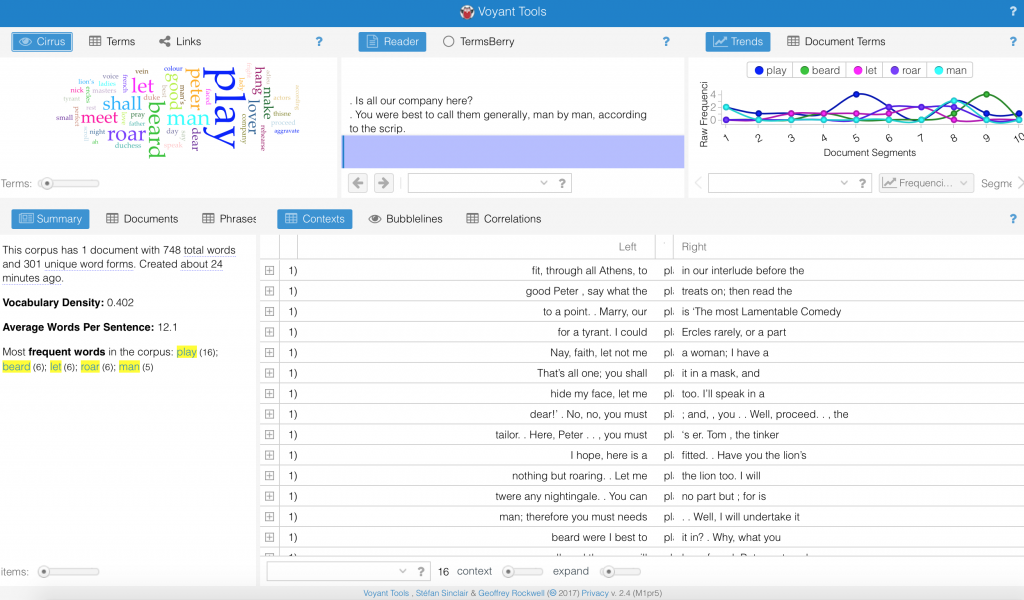

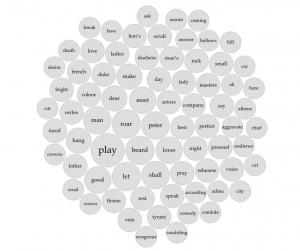

What I find so humorous about this scene is that the exchange between Cleopatra and Antnoy epitomizes the claim that, despite Shakespeare’s title, this is Cleopatra’s play. If we isolate Antony’s lines leading up to the reveal that Fulvia has died, this is what we get:

Now, my dearest queen.

What’s the matter?

The gods best know—

Cleopatra—

Most sweet Queen—

How now, lady?

If left unlabeled, these lines might seem more aligned with the speech of a servant speaking to his mistress instead of the words of a respected general reasoning with his lover. The speech of Cleopatra, in contrast, dances across the page with charisma and a certain degree of childishness, something Cleopatra claims to be rid of.

Using these lines, I would like to consider freedom in Shakespeare’s language: How strict are certain character parameters? How much flexibility do readers and actors have when delivering a character as dynamic as Cleopatra? Take Cleopatra’s last two lines: “Though age from folly could not give me freedom, / It does from childishness: can Fulvia die?” These words carry a lot of weight, but how “should” they be delivered? (With the glee of an adolescent, a degree of snideness, etc.)