Documenting Wealth, Documenting Culture

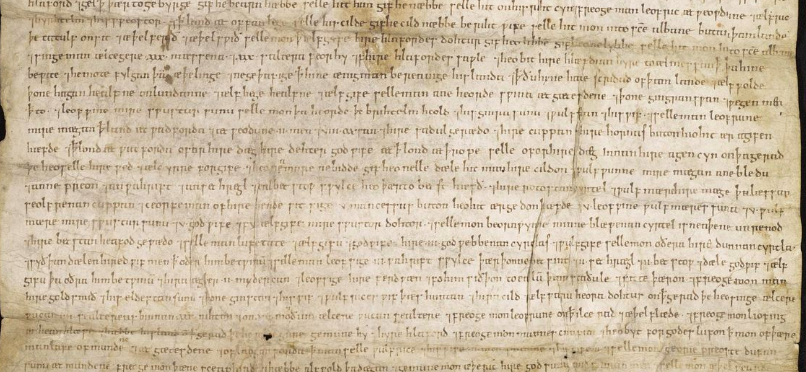

Scheide M140 Front: The document measures 56 x 35 cm and writing for the will itself is on the front of the page only.

Will of Æthelgifu in Old English

England (St. Alban’s?), ca. 990

What is a will? A testimony of the physical wealth that a person possesses and a last act of control as those possessions are divvied out to various benefactors. Money, objects, land holdings, all of these are common within a will, but this example is unusual for other reasons. The Will of Æthelgifu is a lasting document of a woman’s holdings, a well-off woman based on the type and number of things being discussed. Prior to the finding of the Will of Æthelgifu, there were only forty surviving wills that made up the Anglo-Saxon legal funerary cultural literature, none of which are the physical size of this example (56 × 35 cm, or 22 × 14 in), and none of which highlight the variety in day-to-day life as this one does. Through the analysis of this text, both in terms of content, found location and overall preservation of the piece, it becomes possible to gather information regarding slavery in the Anglo-Saxon world, the importance of the Church, agricultural work and familial lineage and even legal documentation regarding court cases.

Endorsement on the back of Scheide M140, likely later than the will itself and thought to be part of a collection cataloguing system.

Looking throughout the text, it largely encompasses the distribution of personal property – land rights, money, household goods, and slaves – to those in Æthelgifu’s inner circle. There is an abundance of named individuals that are both manumitted and given as part of an inheritance to others, with Æthelgifu breaking up families as she freed some members and passed on others to those she deemed worthy. One specific slave, Edwin, stands out because he is a priest in addition to being a slave. The will states that Edwin is to inherit the church which he served during Æthelgifu’s lifetime in addition to a half hide of land and a man, aka a slave of his own, in addition to receiving Byrhstan’s sister, two other women and their children. While this seems like a generous offer, there are stipulations om this, largely that he must keep the church in repair and must perform masses and prayers for Æthelgifu’s soul. This reference to a social interaction brings two realms often regarded as separate together, that a priest can be a slave while still holding some sort of autonomy.

The incorporation of the church does not end with Edwin the priest but is carried throughout the will in multiple ways. There are two types of transactions with the church within the will, transactions that are gifts from Æthelgifu to the church and can be considered social transactions; and those that are payments for services. For examples, St. Albans was given 20 cows as payment for the burial of Æthelgifu but was gifted land at Westwick, land at Goddesden, 30 mancuses of gold, 30 oxen, 150 sheep and a swine heard. It is also frequent within the will that after the initial benefactor’s death, property would be given to St. Albans in exchange for the parish singing masses and dedicating psalters to Æthelgifu. These interactions show that the relationship between the church was mutually beneficial but also complicates the relationship between family ties and religious ties as control over property was dictated for possible generations after the death of the original owner.

Looking closely at the document, which is in excellent condition, minimal decay can be seen in the fold lines of the document where small holes have developed in areas where the folds were subject to greater friction.

A brief but enlightening detail within the will is regarding a legal case around land holdings and the succession of ownership. The will states that Æthelgifu was the benefactor of her husband and obtained her wealth from that, but her sister-in-law took over a land holding despite the will. Æthelgifu then appealed to the King, gave him 20 pounds and he gave her the land back. The will then ends with “If anyone ask that this will may not be allowed to stand, may he be cast on the left hand when the Saviour pronounces his judgement, and may he be as hateful to God as was Judas, who hanged himself; unless she herself change it hereafter, and those be not alive to whom it is now bequeathed.” (Wormald, 16) The ending harkens back to the complications Ætheligifu faced after being left holdings herself as well as harkening back to theological belief of divine intervention/retribution for wrongdoing.

Like wills today, the Will of Æthelgifu is a complex document preserved likely by the St. Albans as benefactor and overseer of interment and then collected by Sir Matthew Hale and later James Farhurst where it made its way into a personal collection. While the unfamiliarity of the scribe’s Insular script and the substantial differences between Old and Modern English make the document unreadable for most people today, the content is telling of Anglo-Saxon culture in relation to social phenomena such as slavery, including who can fall into that category, social and economic transactions with the Christian church and legal cases during the period. The will is also a testament to the agency and power of women throughout the period, factors that are often overlooked or hidden altogether in favor of alternative historical narratives. Through the analysis of documents such as this, the modern world is informed about gender roles, social, theological and legal interactions in ways never before seen.

A possible witness signature on the will, there is debate on if there were at one point additional witness signatures that have been lost based on the possible erasure marks.

Manuscript Citation

Scheide M140. Princeton University Library. [catalog link]

Catalog Reference and Edition

Dorothy Whitelock, The Will of Æthelgifu: A Tenth Century Anglo-Saxon Manuscript (Oxford: Lord Rennell, 1968).

Further Reading

Pat Dutchak, “The Church and Slavery in Anglo-Saxon England,” Past Imperfect 9 (December 2001): 25–42.

Jo Ann McNamara and John E. Halborg with E. Gordon Whately, eds. and trans., Sainted Women of the Dark Ages (Durham: Duke University Press, 1992).

Alexandra O’Hara and Ian Wood, trans., “The Testament of Burgundofara,” in Jonas of Bobbio: Life of Columbanus, Life of John of Réomé, and Life of Vedast, Translated Texts for Historians 64 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017), 311–14.

Linda Tollerton, Wills and Will-Making in Anglo-Saxon England (York: York Medieval Press, 2011).

Digital Facsimile