Here is the passage I choose:

“Here he opened Shakespeare once more. That boy’s business of the intoxication of language—Anthony and Cleopatra—had shrivelled utterly. How Shakespeare loathed humanity—the putting on of clothes, the getting of children, the sordity of the mouth and the belly! This was now revealed to Septimus; the message hidden in the beauty of words. The secret signal which one generation passes, under disguise, to the next is loathing, hatred, despair. Dante the same. Aechylus (translated) the same. There Rezia sat at the table trimming hats. She trimmed hats from Mrs. Filmer’s friends; she trimmed hats by the hour. She looked pale, mysterious, like a lily, drowned, under water, he thought.

“The English are so serious,” she would say, putting her arms round Septimus, her cheek against his.

Love between man and woman was repulsive to Shakespeare. The business of copulation was filth to him before the end. But, Rezia said, they must have children. They have been married for five years.

They went to the Tower together; to Victoria and Albert Museum; stood in the crowd to see the King open Parliament. And there were the shops—hats shops, dress shops, shops with leather bags in the window, where she would stand staring. But she must have a boy.

She must have a son like Septimus, she said. But nobody could be like Septimus; so gentle; so serious; so clever. Could she not read Shakespeare too? Was Shakespeare a difficult author? She asked.”

(Mrs. Dalloway, Oxford World’s Classics, 115-116)

***

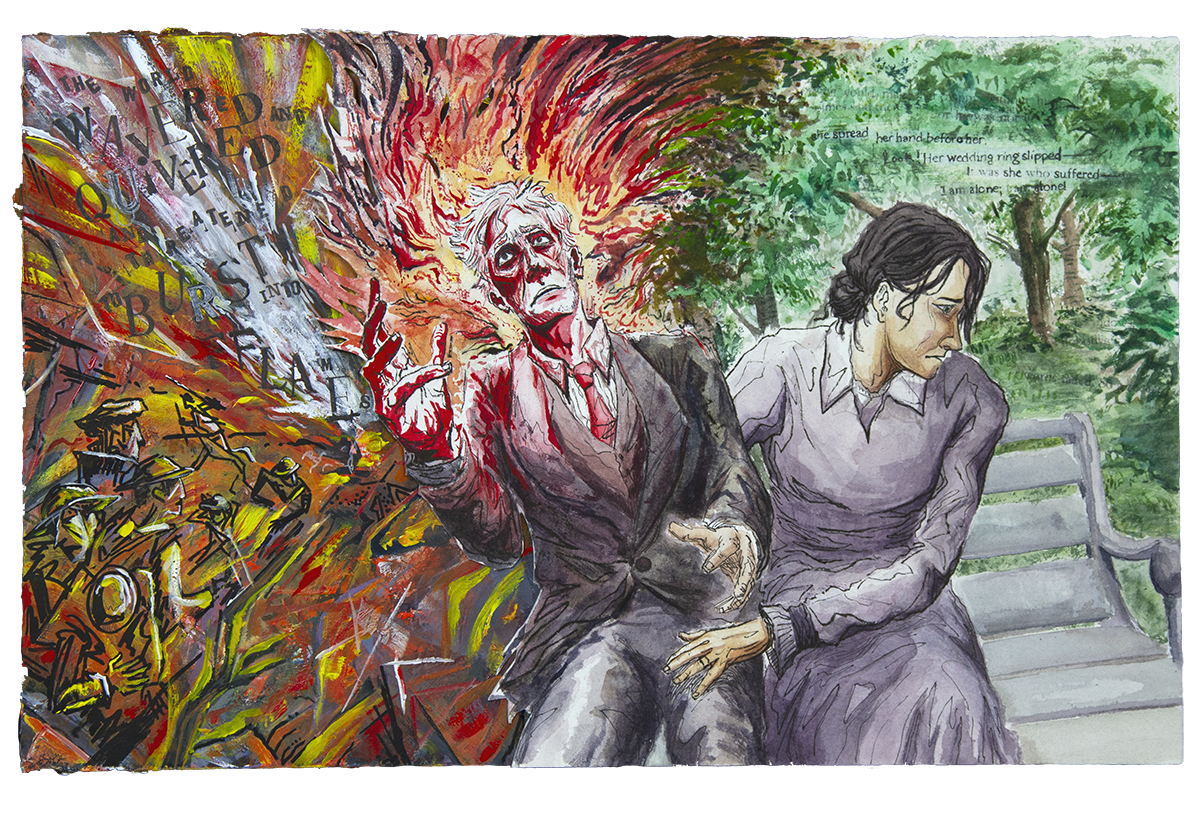

Septimus represents the abstract and Rezia the practical. And as the husband and wife drift apart, their worldviews diverge as well. This passage sketches the deterioration of Septimus’s mind and by extension his marriage.

While Septimus had once found Shakespeare “intoxicating”, he now finds him rather dull. Previously, he had considered Shakespeare a great poet and had even gone to war in his name.

But this has since changed. Now, he merely hears “a boy”, a word he uses to denigrate a poet that is considered a national treasure.

For Septimus, even the act of reading has become “business”, a tiresome chore.

So he assigns Shakespeare a different meaning, one befitting his current state of mind. A parallel is drawn between Septimus’s past and his present: what was once beauty has for him become contempt. He finds life too repetitive and this is captured in the recurring assonance—”putting”, “getting”, and “sordity”. These words deliver the meaninglessness previously only hinted in “business”: what bothers Septimus is not so much life itself but rather the energy and work it requires.

“Beauty” is also contrasted with “loathing, hatred and despair”. This rather defeatist language demonstrates Septimus’s desperation. He moves from one extreme to the other. For him, there is no middle ground. And it all happens in his mind. At one point, he was intoxicated by language. Now, he is depressed by it. Practicality has no significance for him and he is also losing interest in the abstract (represented by Shakespeare)

Rezia is the physical representation of practicality. Her work— the ”trimming” of hats—strikes Septimus as yet another chore. His view of her work can be apprehended in the recurrence of variations of the word “trim”. To Septimus, Rezia is “drowned, under water”. He is unable to make any sense of her work, which is admittedly not done for pleasure but rather out of obligation.

Though practical, Rezia misses to notice the gravity of Septimus’s condition. She is seeking a distraction from work and expects her husband to return her touch, but Septimus remains aloof. Because she is herself a stranger in the country, Rezia attributes her husband’s distance to the nature of the “English”, thus misunderstanding him. Everything she desires is “repulsive” to Septimus: “the business of copulation” and “children”. Rezia even wants “a boy”, the very word Septimus uses to disparage Shakespeare.

In the end, Septimus is repulsed by Rezia as well. His mind is fading and his marriage, too.