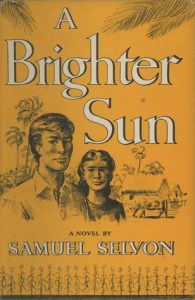

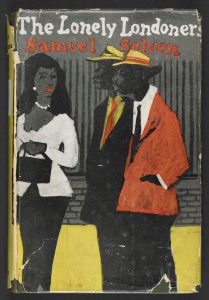

Post-colonialist literature, exemplified by Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners, challenges ideas of race, class and migration within an imperialist context. Kenneth Usongo’s claim that “the movement of the West Indians to England constituted a process of colonization in reverse in that the periphery was moving to the centre” resonates with Selvon’s novel; in many ways, the group of West Indian migrants that Selvon depicts in his text are precisely those unseen voices moving into the forefront (Usongo 182). In the wake of World War Two, West Indians were granted British citizenship as members of the British colonial empire, and began to migrate to London in droves. Although this ‘reverse colonization’ allowed the formerly colonized West Indians to inhabit the same social, political, and economic realms as their former colonizers, Selvon’s novel offers a more complex perspective on the particularly difficult position of West Indian migrants in London. On the one hand, Selvon’s choice to write the novel in dialect subverts British imperial power by allowing the West Indian migrant community to narrate and control their own stories. However, in his depiction of this colonization in reverse, Selvon also acknowledges the continued power white British citizens wield over the formerly colonized West Indian community — particularly via racialized attacks. Throughout the novel, Selvon demonstrates how white Londoners attempt to move the West Indian minority communities back into the periphery of society by employing colonial stereotypes to fetishize Black bodies, ignore Black individuality, or even outright deny the migrants access to skilled labor jobs. The apparent contradiction between Selvon’s subversive use of dialect and his portrayal of these damaging colonial stereotypes reveals the author’s keen awareness of how the particular power structures of ‘reverse colonization’ shaped the unique migration experience of the West Indian community at the heart of his novel.

When examining the style and form of The Lonely Londoners, one of the first things that scholars mention is Selvon’s choice to write the novel completely in dialect. As Kenneth Ramchand notes, the language of the novel is “a careful fabrication, a modified dialect which contains and expresses the sensibility of a whole society” (Ramchand 97). By inflecting his English prose with West Indian dialectical phrasing and terminology, Selvon offers readers a uniquely West Indian lens by which to interpret the migration stories of West Indians. Thus, he grants these migrants ownership over their own narratives and challenges former colonial accounts in which colonizers would rob indigenous populations of agency by writing about them in languages only the colonizers could understand. Additionally, by using dialect to craft his novel, Selvon uses a dual approach of “abrogation” and “appropriation.” Nick Bentley explains that, for a white British reader, the text serves as an “abrogation of the cultural centre” — in other words, the rejection of Standard English exemplifies a rejection of the assumed superiority of white British cultural practices. Meanwhile, for a reader who is a member of the Black migrant community in London, the use of dialect fuels an appropriation process that serves as “an empowering strategy by establishing a specific subcultural identity, and by…subverting the colonial language” (Bentley 76-77). Through this interpretive framework, Selvon’s use of dialect throughout the novel almost becomes a language of resistance as the formerly colonized Black communities take ownership over the language their former colonizers imposed upon them and, in so doing, challenge the authority white Londoners wield over them in cultural spaces. By using this subversive language to narrate a story of West Indian migration, Selvon invites the reader to consider that perhaps migration itself can similarly upend imperialist power dynamics.

But while Selvon’s use of dialect may suggest that West Indian migration subverts British colonial power, he also presents several scenes throughout his novel that demonstrate how white Londoners wield racist stereotypes in order to assert their continued power over the Black West Indian migrants. During his extended prose poem that describes summer in the city, Selvon writes:

“people wouldn’t believe you when you tell them the things that happen in the city but the cruder you are the more the girls like you you can’t put on any English accent for them or play ladeda or tell them you studying medicine in Oxford or try to be polite or civilise they don’t want that sort of thing at all they want to see you live up to the films and stories they hear about black people living primitive in the jungles of the world…” (Selvon 108).

This quote illuminates one of the central problems encountered by the Black West Indian migrants of Selvon’s novel. Despite their migration into the city atmosphere of their former colonizers and their newfound ability to mingle with white women, London is not a fully free sexual space for the migrants. The process of colonization in reverse may allow these peripheral groups to move into the geographical center, but these men are subjected to racist tropes of the ‘native’ or of “black people living primitive” and pushed back into a subjugated role within the dating sphere. They are not viewed as worthy and complex individuals but rather as exotic others who offer only a specific type of crude fantasy for the white women who have sex with them. This discrimination is perhaps most clearly illustrated by Selvon in a separate scene, when an unnamed Jamaican man goes home with a white woman and “the number not interested in passing on any knowledge [about art] she only interested in one thing and in the heat of emotion she call the Jamaican a black bastard” (Selvon 109). In the London that Selvon depicts, Black men are hypersexualized and treated as brutes — racist stereotypes that deny them the opportunity to express their personhood.

Beyond using racialized colonial stereotypes to hypersexualize the West Indian men and fetishize their bodies, the white Londoners of Selvon’s novel also employ colonial tropes in fear mongering efforts against the migrants. Moses notes, “Whatever the newspaper and the radio say in the country, that is the people Bible. Like one time when the newspapers say that the West Indians think that the streets of London paved with gold a Jamaican fellar went to the income tax office to find out something and the first thing the clerk tell him is, ‘You people think the streets of London are paved with gold?’ ” (Selvon 24). The clerk’s use of the phrase “you people” suggests that, to him, the Jamaican man is just one of a nameless, faceless horde of Black West Indians that are streaming into the city in search of work. Additionally, Moses echoes the phrase “streets paved with gold” when he is warning Galahad about what to expect from the white British public in his hunt for a job. “To them you will be just another one of them black Jamaicans who coming to London thinking that the streets paved with gold,” Moses tells Galahad (Selvon 41). The concept of “streets paved with gold” is highly reminiscent of the insatiable lust for gold revealed in the language white colonizers used to describe their hopes for what they might find in new lands like the West Indies. When those hopes were largely dashed, the white colonizers were still able to take control of the new lands, subjugate the indigenous communities, and win acclaim from their home nation. Yet for the West Indians moving to London, the same colonial phrasing is used derisively and employed mostly to suggest the migrants’ incredible ignorance about the city. Rather than arriving into the new cityscape and becoming the conquerors, the West Indian migrants are treated as an uncultured, uneducated mass of “you people.”

But the Black West Indian migrants in Selvon’s novel don’t just face discrimination in the words white Londoners wield against them. Because they are Black, the migrants are also forced into certain jobs due to a filing system used by the government. Moses informs Galahad about a mark that he will see on the records of all of the Black migrants: “J—A, Col.” He elaborates on the meaning of this mark, saying, “That mean you from Jamaica and you black” (Selvon 46). According to Moses, this is helpful because it allows the people who work at the employment office to first find out if a specific firm will hire Black people before they send the West Indian migrants to fill any vacant positions — saving “time and bother” (Selvon 46). Just what kind of jobs West Indian migrants might be deemed acceptable for is further defined by Moses when he expresses his frustration at the lack of employment opportunity to Cap. He says, “They send you for storekeeper work and they want to put you in that yard to lift heavy iron. They think that is all we good for, and this time they keeping all the soft clerical jobs for them white fellars” (Selvon 52). Once again, West Indian migrants are kept in a quasi-colonial, subjugated state even as they move into white spaces within London. Rather than being afforded the opportunity to progress economically, Black West Indians are forced into lower-paid, unskilled jobs that require physical labor of them — work that is not dissimilar to that which would have been required of them during Britain’s former days as an imperial power. Stephen Wolfe identifies the discussion between Galahad and Moses about the practices of the employment office as one that “forces Galahad to negotiate his colonial otherness” (Wolfe 131). Like any other British citizen, Galahad has been welcomed to apply for employment; however, unlike white British citizens, the racial identification on Galahad’s file limits the job opportunities he has access to.

By depicting the ways in which Black West Indian migrants are broadly discriminated against by white Londoners, Selvon appears to suggest that the traditional power structures of British imperialism were maintained in London — seemingly contradicting the subversion of such power structures implied in his choice to write the novel in West Indian dialect. With this in mind, it is worth returning to Selvon’s decision to use dialect to see if he may be employing the technique to create more than just a language of resistance or of empowerment. Bill Ashcroft presents a useful interpretive framework in his discussion of a “metonymic gap,” which are the phrases and references that a writer might insert into their novel that may be unknown to a reader of the colonizer culture. According to Ashcroft:

“The local writer is thus able to represent his or her world to the colonizer (and others) in the metropolitan language, and at the same time, to signal and emphasize a difference from it. In effect, the writer is saying, ‘I am using your language so that you will understand my world, but you will also know by the differences in the way I use it that you cannot share my experience.” (Ashcroft 74-75)

In some ways, writing his novel in a modified version of Standard English does allow Selvon to present West Indian migration to London in a way that challenges the previously unquestioned presumption of British cultural supremacy over colonized cultures. However, Ashcroft astutely notes that modifying Standard English with dialect implies both a kinship and an impossible distance between the cultures of the former colonizer and the formerly colonized — the latter of whom has an experience that can never be fully articulated to or understood by the former. As Galahad’s date, Daisy, says, albeit more crudely, “You know it will take me some time to understand everything you say. The way you West Indians speak!” (Selvon 93).

As much as Selvon’s use of dialect adds power to the West Indian cultural experience in London, it also reminds his readers that West Indian migrants had a unique expectation when they arrived in London. Because the West Indians grew up in British colonies and were granted British citizenship, they “had arrived in Britain considering themselves to be British and expecting to be treated as such, yet they found the rudiments of respectability—a job, a wife, a home, independence —being withheld by a host society which betrayed their expectations” (Collins 417). Unlike the Polish restaurateur — who Moses identifies as a foreigner yet still someone who wouldn’t deign to serve the Black West Indian migrants — these men were “British subjects” and “[bled] to make [Britain] prosperous” (Selvon 40). The language of the West Indian migrant community is English, even if a modified version of its standard form. Sam Selvon very intentionally places the migration depicted in this novel against the concept of ‘colonization in the reverse’ to explore the ways in which their status as formerly colonized people impacts the particular migration story of West Indians in London. While there is a subversion of British power when the West Indians move into British geographical space and begin to socialize with London natives, there remains a sense of British colonial authority over the West Indians in London that presents itself in racially-charged colonial tropes and forced unskilled labor. By probing this continued colonialism vs. subverted colonialism dichotomy, Selvon ultimately advances a compelling argument for why West Indian migration into London was a particularly painful process compared to the experiences of other migrant groups. When they gained rights as British citizens and subsequently moved to the center of the former empire, Black West Indians had every reason to expect a warm welcome from their British family. Instead, racist stereotypes deeply rooted in colonialism allowed white Londoners to assert power over Black West Indians and shove them back out into the societal periphery.

Works Cited

Ashcroft, Bill. Post-Colonial Transformation. London, Routledge, 2001.

Bentley, Nick. “Form and language in Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners.” ARIEL, vol. 36, no. 3-4, 2005, p. 67+. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A160750019/LitRC?u=prin77918&sid=LitRC&xid=4cb6d0a8. Accessed 7 May 2021.

Collins, Marcus. “Pride and Prejudice: West Indian Men in Mid-Twentieth-Century Britain.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 40, no. 3, 2001, p. 391-418. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3070729. Accessed 7 May 2021.

Herald, Patrick. “‘The Black’, space, and sexuality: Examining resistance in Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners.” The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, vol. 52, no. 2, 2017, p. 350-364, DOI: 10.1177/0021989415608906

Ramchand, Kenneth. The West Indian Novel and its Background. Jamaica, Ian Randle Publishers, 2004.

Selvon, Sam. The Lonely Londoners. New York, Longman Publishing Group, 1998.

Usongo, Kenneth. “The politics of migration and empire in Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners,” Journal of the African Literature Association, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, p. 180-200, DOI: 10.1080/21674736.2018.1515567

Wolfe, Stephen F. “A Happy English Colonial Family in 1950s London?: Immigration, Containment and Transgression in The Lonely Londoners,” Culture, Theory and Critique, vol. 57, no. 1, 2016, p. 121-136, DOI: 10.1080/14735784.2015.1111157

I pledge my honor that this paper represents my own work in accordance with University guidelines. — Alexandra Gjaja