A Reflection on The Mangrove: An Investigation on the effects of McQueen’s cinematography on his presentation of 1960’s London

Steve McQueen’s film The Mangrove illustrates the violence faced not only by direct immigrants but by their descendants as well. As the son of first-generation immigrants, McQueen had firsthand experience with deeply ingrained racism towards immigrants widespread in the United Kingdom. The Mangrove centers around the “mangrove nine” who were wrongly accused of inciting a riot after months of being unfairly targeted by local police.[1]McQueen deftly moves the viewer through the film so as to paint a full picture of how the unique problems faced by the West Indie community in Notting Hill came to reflect the prevalence of racism in the justice system throughout the United Kingdom.[2]McQueen manipulates elements of film – such as camera angle, setting, and music – to offer different points of view on the Mangrove Nine’s story. His film tactics allow for an all-encompassing portrait of the underlying issues at play in the film – namely the desire of White authority figures to disallow the Black immigrant community from fostering any sense of community or self-sufficiency. Using the Notting Hill neighborhood as a microcosm of the greater United Kingdom, TheMangrovehighlights how pervasive corruption was in the 1960’s justice system that allowed for Black citizens to be terrorized.

The Mangrove uses setting to illustrate both sides of the war for survival. The black individuals centered throughout the film represent a desire of community and stability in the midst of constant and oftentimes random violence. On the other side, the White members of the justice system represent a desire to disallow the black immigrant population from establishing themselves in British culture, looking at them as an affront to British society and values.[3]Each location illuminates a different element of the immigrant experience and the fight for justice. The first half of the film bounces between The Mangrove restaurant, police quarters, and the streets as McQueen builds the tension. The second half is almost entirely confined to the Old Bailey courtroom as the 11 weeklong trail unfolds.[4]Finally, the viewer is brought back to Notting Hill to celebrate a hard-earned win for the Black community. McQueen uses lighting, set, and sound to foster different feelings within the viewer as we move through the film while at the same time giving voice to a community that has been historically marginalized in British society.

At the start of the film, The Mangrove restaurant acts as a center of the Black community in Notting Hill. While The Mangrove’s owner, Frank, consistently asserts that his restaurant is “just like any other restaurant,” it is clear from the beginning of the film that that is not the case.[5]In the scene depicting the Mangrove’s opening night, the restaurant is filmed in warm light as the patrons are bathed in a homey orange glow. The camera pans around the restaurant as if you are viewing the scene as a patron yourself, showcasing the lively banter that fills the space. McQueen has the music of steel drums play over the lively sounds of conversation, bringing the sounds of the west indies to London. As the steel drums weave through the patrons and move outside, the characters flow into the street dancing and drinking around them in a festive ambiance. Through allowing his characters the space to flow freely from inside to outside the Mangrove, McQueen illustrates how the restaurant instilled a sense of safety in its patrons that extends outside of the its physical borders. All these elements work together to provide the viewer with a feeling of community and happiness, visually placing the Mangrove at the center of the film as McQueen uses the space to represent home and community.

McQueen consistently contrasts the happiness of The Mangrove with the sterile, dark environment of the police station and their patrol cars. In the viewers first introduction to PC Pulley, the sadist police officer who terrorizes Notting Hill’s Black community, he is shrouded in the darkness of a cop car looking out into the night as though stalking his prey. Pulley’s face is the sole focal point of the scene as he is illuminated by outside streetlight in an otherwise pitch-black car. In the first five seconds there is no noise apart from the muted music and chatter coming from The Mangrove. The silence is broken by Pulley when he says, “See the thing about the Black man is he has his place… He’s just gotta know his place. If he oversteps, he’s gotta be gently nudged back in.”[6]As he speaks, the camera angle switches and appears to enter his vision as McQueen shows a view of The Mangrove from inside the patrol car. Where the mangrove was bathed in orange hues in the prior scene, it is now slightly unfocused and illuminated primarily by its green sign – the community the viewer was watching just minutes ago now hidden from view. It appears as though this view of the Mangrove is colored by Pulley’s extremely overt hatred of the Black community as the viewer sees it from what appears to be his own eyes. In contrast to the fluid movement of the camera angles inside the Mangrove, the camera is stilled in this scene as it switches from Pulley’s profile, to Pulley’s view of the Mangrove from the police car, to Pulley’s partner. The ambiance of the scene is a polar opposite to the liveliness of the Mangrove that directly proceeded it. By juxtaposing the Mangrove’s opening scene and Pulley’s view of it with one another, McQueen visually introduces the tension that is to unfold throughout the rest of the film.

McQueen continues to use lighting and sound to portray the coldness of the police who calmly inflict pain and terrorize the Notting Hill community. He periodically moves the viewer to the police station and their patrol cars to illustrate the police officer’s apathy towards the community they are allegedly serving. For example, in the police station scene, the viewer is privy to a ‘behind the scenes’ picture of the police’s overt prejudice. The office is coldly lit with white light that creates a sense of ominous foreboding in the viewer. It is interesting to note that directly preceding this sterile scene the viewer was in the midst of a colorful street festival outside The Mangrove. Where the previous clip was filled with music and energy the viewer is now confronted with silence only interrupted by the sound of darts hitting the wall and PC Pulley’s unsettling comments. While the viewer already has a feeling that something is going to happen, the direction of the scene becomes clear when PC Royce says, “whoever draws the Ace of Spades has to go out and nick the first Black bastard they clap eyes on.” McQueen brings the viewer along for the insidious event, placing the camera inside the patrol car as if we are complicit in this crime of hate. The soundscape is, yet again, almost entirely silent apart from the rain and screeching of tires as the police chase the innocent man. The darkness of the scene gives it an ethereal feel and seems almost like a horror movie. Through these two scenes, McQueen illustrates the constant danger faced by the Black community on the streets that should be their own.

The streets, while a place of fear, also act as the setting for the beginning of justice as the tension between the Black community and the police culminates in a protest meant to call out the Police’s unjust harassment of the Mangrove. McQueen places Altheia at the center of the crowd as she acts as the voice of the people, calling attention to the fact that the oppression faced by the Mangrove is not an isolated event. A light rain persists throughout the scene, casting a grey light is over the demonstration. The use of rain draws a parallel between the protest and the earlier scene of the police chase as we watch Altheia’s reflection through a rain splattered window. As the group mobilizes and begins its march to the police station, McQueen highlights individual faces as they chant, “Black power,” humanizing the crowd. Conversely, the mass of police officers who encircle the protest are almost faceless as they dissolve into a swarming mass. McQueen only films the officers’ feet as they stream out of the police station towards the crowd, taking away their individuality as they hurl insults at the peaceful protestors. As the tension builds between the two groups, the camera angle begins to jostle between frames. This manipulation of angle and frame makes the viewer feel as though they are a part of the crowd, providing a sense of confusion and fear. The Black community uses this demonstration to give themselves a voice in the face of systemic injustice. Despite the protest being for The Mangrove, it also applies to the injustices faced by all Black citizens of the United Kingdom.

The second half of the film marks a moment of transition as what was a unique Notting Hill issue becomes a problem of national importance. Nearly the entire second half of The Mangrove takes place in the Old Bailey Courtroom, a place “normally reserved for only the most serious of crimes.” The setting itself does a lot of work for the film. Placing the proceedings for a decidedly peaceful crime in a building defined by violence represents an unequal playing field as well as the intimidation tactics employed by the government to silence Black voices. The physical nature of the court room serves to separate individuals from one another. Where the camera moved smoothly around the flowing tables of the Mangrove it now sits stagnant in the rows of the courtroom. McQueen places the viewer in various parts of the courtroom as the camera angle moves from the balcony to the witness stand to the jury to the prosecution. This manipulation of angle gives the viewer a sense of being inside the court with the defendants. When panning through the court room, McQueen stills the camera on the protest signs affixed to the witness stand. The signs are beacons in an otherwise antique looking room – illustrating the presence of a new energy in the court. Throughout the hour of the film spent in the Old Bailey, McQueen peppers in reggae music such as Skinhead Moonstop over the proceedings. Yet again, this stylistic choice inserts the Mangrove Nine’s west indie heritage into the stuffy, historical British building.

Two of the defendants, Howe and Altheia, decide to represent themselves in court allowing them to “take [their] message inside the building… and talk directly to the jury,” and transition from “victims to protagonists of their own stories.”[7]Throughout their time in court, the defendants find ways to work the court’s prejudice against itself, taking charge of the narrative. In the court’s final testimonies, McQueen presents Howe in soft light which illuminates him as he takes his stand. Unlike the rest of the defendants and prosecution who are clothed in dark colors, Howe is wearing white and blue. This stylistic choice places Howe apart from the courtroom, yet again illustrating a new energy that is asserting itself. As Howe’s speech progresses the camera angle pans upwards to show members of the Notting Hill community above him. The angle gives a sense of community as the audience lifts Howe’s words and project them through the court room. When the verdicts are finally given, instead of moving the camera through the room McQueen keeps it statically posed on Frank’s face. The scene conjured up Howe’s quote before the protests when he told Frank, “I see a man who has become a leader to his people… leaders who are rooted deeply in the people they lead.”[8]Frank took up the burden of leadership when all he wanted was peace. By centering the Mangrove Nine’s win on Frank, McQueen is affirming his position within the group and allowing Frank the space to savor the win for justice.

The Mangrove embodies McQueen’s ability to showcase the “interplay between the pleasures and frustrations of everyday life and the larger struggles around race, class and state power in post-imperial Britain.”[9]To end the film, McQueen brings the viewer back to Notting Hill where it all began. Finally free from the stress of the court room, the viewer is yet again placed in the homey Mangrove restaurant. The camera follows Frank as he flows through the patrons, a far cry from the mostly stilted camera angles of the courtroom. Outside the Mangrove, Frank talks to Dolston who says he is “going home,” to which Frank counters, “This we home Dol. The Mangrove.” This claim is powerful as the viewer knows just how arduous the journey to justice and homecoming was for Frank and the rest of the Mangrove Nine. As the scene closes, the soft tune of Toots and the Maytals’ “Pressure Drop” plays as a triumphant song about karmic justice.[10]The song is a fitting way to end the movie as it leaves us with lyrics promising those who do bad against he innocent will have a storm coming to them.

WORKS CITED

- Steve McQueen, The Mangrove, Small Axe Series,

- Nitish Pahwa, “What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Steve McQueen’s Mangrove”, Slate, November 20, 2020.

- Professor Schor, London Literature Lecture Notes.

- AO Scott. ‘Mangrove’ Review: A restaurants Radicalism. November 19, 2020.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/19/movies/mangrove-review-small-axe.html

- Catherine Baksi, Landmarks in law: When the Mangrove Nine beat the British State. November 10, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/law/2020/nov/10/landmarks-in-law-when-the-mangrove-nine-beat-the-british-state

- Diane Pien, “Mangrove Nine Trial”, Black Past, July 2, 2018. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/mangrove-nine-trial-1970-1972/

‘An Unstoppable Force’: Secrecy and Transgression in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane

This essay represents my own work, in accordance with University regulations.

“It was as if she had woken one day to find that she had become a collector, guardian of a great archive of secrets, without the faintest knowledge of how she had gotten started or how her collection had grown. Perhaps, she considered, they just breed with each other. And then she imagined her secrets like a column of ants, appearing at first like a few negligible specks and turning so quickly into an unstoppable force” (228).

Introduction

Unlike adventurous protagonists in the tradition of the realist novel such as Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, Nazneen is confined to the domestic arena and draws her power only from within. This is hinted at in the epigraphs announcing fate as the major theme of the novel. Because each of Nazneen’s attempts to forge into the outside world is considered a transgression in her society, she turns into a “guardian of a great archive of secrets”: her first walk in the city; her sister’s despair; her knowledge of Tariq’s descent into drugs, and most significantly the affair with Karim, are all secrets. While her husband, Chanu, conceals to abscond responsibility and soften his wounding humiliations, Nazneen uses secrecy to test the suffocating social boundaries around her before eventually breaking free from them.

As the secrets compound, the gulf between Nazneen and her husband widens, and by the end of the novel, the roles of husband and wife in the family have completely reversed. Secrecy allows Nazneen to ascertain her power and attain selfhood, sharpening her perception and allowing her to establish roots in the city, even as the marriage crumbles.

I: Quiet Rebellion

Mishra (2003) finds Chanu’s depiction is fuller than Nazneen’s. This is indeed a correct first impression. But if one takes Nazneen’s secrecy into account, she acquires a more complex interiority. In the first half of the novel, Nazneen’s secrets afford her a quiet rebellion, a profound rejoinder to Chanu’s hollow tirades.

While Chanu’s past is only one of glory, Nazneen’s is more nuanced. She clings to the legend of her nativity: Nazneen had been taught that she had survived her childhood only because she was surrendered to fate. Her mother, Amma, downplays the role she had played in nursing the daughter and instead attributes it to fate. This grants the child freedom from life’s drudgery and banishes all ambition. For a woman, the desire for self-improvement is itself considered a sin. But Nazneen’s life is nothing but toil: she submits to her father, who marries her off to Chanu. And at her house, she essentially becomes a maid, tending only to Chanu’s needs: she cuts his corns and trims his nails. Because there is no satisfaction in such humiliating work, Nazneen falls back into her mother’s philosophy: she surrenders to fate, which justifies the toil and gives her a different source of purpose, a purpose she may have found in a job of her own. Unrooted and displaced in London, Nazneen grounds herself in tradition. She draws resilience from the conviction that there is nothing she can do about her life. “What could not be changed must be born,” was how Amma had put it (p. 4). But the toil becomes too unbearable for Nazneen and she quietly rebels. These transgressions gather into secrets.

When Jorina, a woman in the neighborhood, commits suicide, Nazneen is concerned. The news is broken by Mrs. Islam, whose authority over the neighborhood rests solely on her archive of secrets. For women, secrecy is a source of power. This is made more explicit when Nazneen inquires about why Jorina had killed herself. “You can hardly keep it a secret when you begin going out to work,” Razia theorizes (p. 13). The woman’s sin, it turns out, was that she had found a job for herself. This piques Nazneen’s curiosity. She formulates a question about Jorina’s death, rephrasing it endlessly, but she never gathers enough courage to pose it to Chanu. This sets the ground for her rebellion.

When Nazneen accompanies Chanu to Dr. Azad’s practice, he introduces her as “shy”, but she locks eyes with the doctor, finding herself “caught in a complicity of looks” (p. 19), which threatens to give off what her husband is not saying. Although she has no role in the conversation, she still manages to tip Chanu off. Nazneen also represses her desire to act, secretly hatching plans in her head, which compensate for her passivity. “She wanted to get up from the table and walk out of the door and never see [Chanu] again” (p. 18). So forceful is her desire for rebellion even when she is completely subdued.

Nazneen’s first true transgression is the walk she makes to the city by herself, unaccompanied by her husband. This journey represents independence. Chanu confines her to the house, locked from the outside world. Embarrassed, he also hides the details of his job from Nazneen. He wants to live with her in the same house but still somehow maintain a distance, keeping the assaults against his manhood only to himself. Even in his ramblings, Chanu manages to remain obscure, rarely briefing Nazneen on the true contents of the books he reads, claiming that they are not easy to translate. This forces Nazneen to forge into the city on her own. And when she takes the walk to the city and makes it back to her house safely, having asked for directions, this cements Nazneen’s power and bolsters her self-confidence. “See what I can do,” she says to herself, addressing Chanu, although she cannot yet summon the courage to tell him about the walk (p. 40). At least she discovers she no longer has to rely on him. And this must be kept a secret: he wields too much power over. If Nazneen confesses her transgression, Chanu may restrain her and this is not a risk she is ready to take.

But Nazneen finds a different outlet for action. Her sister, Hasina, writes to her from home to tell her that she had escaped from her husband to Dhaka. This is Hasina’s secret and no one in the village knows about it. Nazneen is convinced her sister’s action will put her in great peril. “Once you get talked about, then that’s it,” she confirms (p.38). A woman is only safe as long as she remains servile to her husband; if she breaks free, that is the end for her, as has been the case of Jorina. Nazneen is worried such a fate is awaiting her sister and she appeals to Chanu for action. But Chanu downplays the sister’s case and instead sympathizes with the husband, whom Hasina had confessed had brutally beaten her. “What will happen will happen,” Chanu says, echoing Amma’s philosophy of submission to fate. Nazneen feels betrayed and withholds Hasina’s future letters from her husband. This, she believes, is a case she must take up on her own. For the first time, she punishes Chanu for the grievance. She stops praying for his promotion, puts “fiery chilies’ into his sandwich, slips the razor when cutting his corns, and registers her rebellion in all the chores she undertakes (p. 40). But Chanu barely notices Nazneen’s discontent. If anything, he suppresses her even more. For instance, when Nazneen suggests enrolling in Razia’s college, Chanu feigns indifference (p. 51). This confirms to her that she cannot rely on him for anything. Nazneen must rebel more fiercely.

II: The Affair

Walter (2003) finds fault with Hasina’s letters, writing, “I don’t quite understand why Hasina’s letters are written in such broken prose, since presumably she would write in her own language”. This ignores the fact that spelling mistakes can also occur in the Bengali language. But the true distinction between the sisters is one of temperament. Nazneen admires Hasina’s broken spelling and finds her correspondence more lively than her own letters, which are anguished and forever in search of perfection. Gorra (2003) lucidly captures the true intention of Hasina’s letters. “Hasina’s account of her life in a desperately poor city [tells] Nazneen that the “home” she imagines no longer exists,” he writes.

Hasina’s desperation is clearly overstated. Mishra (2003) points out that Hasina “sounds more like a travel writer from England than an oppressed Bangladeshi woman”. However, there is no doubt that Hasina’s grim experience back home alleviates Nazneen’s nostalgia and grounds her in the city. This is a secret she withholds from the tormented Chanu, until later in the novel. But her sister’s correspondence is not enough solace for Nazneen. The “external three-way torture of daughter-father-daughter” becomes too unbearable for her (p. 147).

This slowly leads to Nazneen’s biggest secret. Estranged from her husband, Nazneen begins dreaming of finding a job for herself and sending money to Hasina (p. 133). She swings into action and masters “basting, stitching, hemming, buttonholing and gathering” (p. 139). In this way, she invents a job for herself without leaving the house, as Jorina had been forced to do. At this point, Nazneen also finds out that Chanu had taken a loan from Mrs. Islam and she confronts him about it. As always, he merely ignores her. But when Nazneen starts working at home, Chanu does not ask her to stop; instead, the roles of wife and husband reverse and he begins helping her, “passing scissors, dispensing advice, making tea, folding garments (p. 147.” He desperately wants to be in charge, even calculating the profit margins on her behalf. Chanu is unmotivated and he has given up his big ambitions. He has essentially resigned to fate. “Now, I just take the money, I say thank you. I count it,” he says (p. 154). This sense of despair bothers Nazneem and she desperately wants an escape.

This is when Nazneen falls for Karim, the middleman who brings her the garments. Unlike Chanu, Karim is a man of action; in fact, his favorite catchphrase is “man”. Though he is of the same generation as Tariq, Karim is different. Where Tariq steals from his mother (saying “Ok-Mama” to everything she says) and succumbs to drugs (a secret Nazneen picks on early but never discloses to Razia), Karim rebels from his parents and loathes them intensely. He scolds his father for spending too much money calling back home and faults him for growing passive after decades of driving. Karim just cannot stand weakness and this attracts Nazneen to him.

In Nazneen’s eyes, Karim accounts for Chanu’s weaknesses: he is confident and knows his place in the world. And he gives her the attention she needs. Being an Islamic activist, Karim brings Nazneen leaflets and slowly radicalizes her. This allows her to avenge Chanu for a lifetime’s grievances. “You are not the only one who knows things,” she would retort, secretly and only to herself (p. 176). But Chanu still remains indifferent, even oblivious. Threatened by the leaflets, he finds mistakes in them, claiming they give “a wrong impression of Muslims” (p. 188), though he is himself not a practicing Muslim. But this does not discourage Nazneen. The secrecy of her affair with Karim and the possibility of Chanu finding out only intensifies her desire (p. 188).

The affair permits Nazneen to break free from the philosophy that she had inherited from her mother (and subsequently Chanu) and grants her urgency, almost instantly. “For a glorious moment,” we are told, “it was clear that clothes, not fate, made her” (p. 201). This allows her to bridge the barrier between her and Karim, while at the same time drawing closer to her daughters, who are of the same generation. And as soon as Chanu alienates Shahana by calling her memsahib and addressing her through her younger sister, Bibi, she begins confiding in Nazneen. The immensity of the transgression (considered to be the biggest sin in Islam) endows Nazneen with a fearlessness she had never known before. The city also justifies her action: Nazneen overhears the “rhythmic knocking” from the bed of her next-door neighbor, who drops one new boyfriend after another, and this allows her to view her own affair as nothing out of the ordinary (p. 221).

III: The Epiphany

After the affair, Nazneen changes and begins to use her power: she stands up to Mrs. Islam, who had been bullying her with her two sons for a long time; she breaks up with Karim after realizing he is not the man she had imagined him to be, and she refuses to return back home with Chanu when he acquires the tickets. These are all out of sync with Nazneen’s temperament in most of the novel. The secrecy takes on an outward force, which surprises the reader. Yet, even when she awakens, Nazneen still lacks a strong conviction. Though she refuses to return home, she does not entirely abandon Chanu and one can imagine her sending money to him.

Therefore, Brick Lane leaves loose ends. For instance, no reason is provided for why Nazneen does not tell Razia about Tariq’s descent into drugs, although the two are close friends. And the epiphany about Karim comes too suddenly. Moreover, the relationship between Chanu and Nazneen continues to linger on. These moments can all be seen as an extension of Nazneen’s passivity. Hiddleston (2005) argues that the novel operates on “shapes and shadows”, playing with “provisional forms, rather than determinate individuals or incontrovertible truths” (Hiddleston, 71). In a sense, the novel is itself cast as fate, unrooted, uncertain of itself. It becomes a secret to unravel. This hesitancy in the narration is one Ali herself confesses in a 2003 essay in The Guardian. “Standing neither behind a closed door, nor in the thick of things, but rather in the shadow of the doorway, is a good place from which to observe,” she writes. But I am convinced that these are just the faults of a debut novel. Although Nazneen’s epiphany comes too late and lasts only briefly, I think this force can be gleaned even in the early pages if one pays attention to her power for secrecy.

Conclusion

Nazneen’s power gathers slowly, almost like an army of ants, and this is driven by her talent for secrecy. These secrets allow Nazneen to transcend the social boundaries and eventually take control of her fate. But the journey to this moment is too slow and it comes too swiftly, which necessitates close attention to detail, particularly the secrets.

Bibliography:

Hiddleston J. Shapes and Shadows: (Un)veiling the Immigrant in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 2005;40(1):57-72. doi:10.1177/0021989405050665

Micheal Gorra, “East Enders”, The New York Times, September 7 2003. Available here.

Monica Ali, Brick Lane. New York: Scribner, 2003.

————— “Where I am Coming From”, The Guardian, June 17 2003. Available here.

Natasha Walter, “Citrus Scent of Inexorable Desire”, The Guardian, June 14 2003. Available here.

Pankaj Mishra, “Enigmas of Arrival”, The New York Review of Books, December 18 2003. Available here.

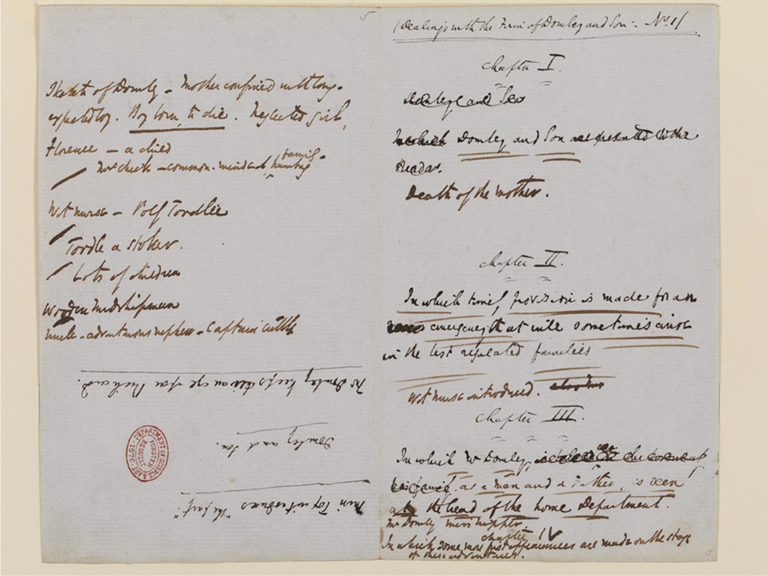

The Many Londons in Dombey and Son

The world is ever-changing, and London in the 1840s was changing more rapidly than most places in most time periods. Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens is a novel trying to come to terms with this change. It is a novel with one foot in the past and the other in the present, exploring post-industrial life with its new technology, new business, and new society. There is an element of uncertainty that comes with change, and Dickens examines the effects of these uncertainties through his multigenerational account of the Dombey family. Professor of Victorian Literature Catherine Waters notes, “Dombey and Son marks the beginning of Dickens’s engagement with the family as a complex cultural construct, exploring the connections between familial and economic relations” (127-8). As a result, the family is a reflection of the society in which it lives and likewise constantly changing, because in Dombey and Son, London is defined by change.

Trains and railways mark the death of an earlier London in Dombey and Son and also function as markers for significant changes for the life of the Dombeys. Professor of English and founding director of The Dickens Project Murray Baumgarten writes, “Dickens understood that his was a world in transition, and that it was defined not just by the modern habits it was moving toward but the traditional habits it was leaving behind” (111). Perhaps no passage exemplifies this transition as vividly as the description of Camden Town early in the novel when Polly Toodle is taking Paul, Florence, and Susan with her to visit her home.* “The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre” (Dickens 63). Dickens has not yet revealed what is causing this commotion, but whatever it might be is clearly unsettling and devastating, like an earthquake. Before the reader has the opportunity to find their bearings, the setting is introduced by recounting how the ground feels—shaking—followed by the horrifying visual companion: “Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped…Here, a chaos of carts, overthrown and jumbled together, lay topsy-turvy at the bottom of a steep unnatural hill” (Dickens 63). The moment that is supposed to be a homecoming for Polly is interrupted by chaos—she cannot return to the Camden that she knew—and suspense is built as the description continues. The reader does not know what has happened here, but it is worse than an earthquake, because this is an “unnatural” and intentional disaster.

That the damage is a by-product of construction work is particularly jarring due to the juxtaposition of the detailed description of destruction with the curt reveal. “In short, the yet unfinished and unopened railroad was in progress; and, from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilization and improvement” (Dickens 63). This one sentence is a paragraph onto itself following the longest paragraph in the chapter with its lofty sentences dedicated to unpacking the specific consequences of industrialization in a community. The sudden change in tone matches the visual contrast on the page. Dickens is mocking the idea of linear progress. He does not think continuing to build suspense is worth the mundane reveal, which creates an impatient and dismissive tone. “In short,” the reader surely knows what is going on: the railways are championing modernity; they are the vanguard of progress. Dickens is playing with the common image of industrialization as “mighty” and an unambiguous sign of “civilization and improvement” by showing the “dire disorder” that the railway leaves behind.

There is implicit class critique in Dickens’s portrayal given that the construction affects the neighbourhood of little Paul Dombey’s nurse. It is almost impossible to imagine a similar situation occurring near Mr. Dombey’s mansion “on the shady side of a tall, dark, dreadfully genteel street in the region between Portland Place and Bryanstone Square” (Dickens 24). Camden is in contrast with the quieter, wealthier Dombey neighbourhood, and this dichotomy is played up to an extreme level later when Florence is separated from Susan and the rest of her group because of a mad bull. What is more, Polly is as shocked by the railway as the rest of her group, highlighting the fact that she has been away from her family and home due to the demands of her job. It is almost as if she moved to a different city and not a different place within the same city. The text does not let the reader forget Polly’s job by referring to her as “Richards,” the name given to Polly by Mr. Dombey (Dickens 63). Professor of English John Mullan observes, “The renaming is so wonderfully unnecessary—such a foolish assertion of power” (135). In addition, the renaming further distances Polly from her family. The railway, like Polly’s new work name marks change.

Another critical moment in the plot that both signifies a change for the Dombey family and London is Mr. Dombey’s train ride to Birmingham. Little Paul—the Son in Dombey and Son—is dead, and the train is leading Mr. Dombey to his soon-to-be second wife, Edith. Understandably, the tone is much more morbid than the description of the construction at Camden. Mr. Dombey “found no pleasure or relief in the journey,” because he is grieving, and the train comes to symbolize death (Dickens 261). Even though Dickens had already written about the damage caused by the construction, his tone was slightly more playful then. Now, “the very speed at which the train was whirled along, mocked the swift course of the young life that had been borne away so steadily and so inexorably to its foredoomed end” (Dickens 261). Dickens is serious, angry even, because Mr. Dombey’s emotions overshadow all else. The train is a death machine “that forced itself upon its iron way—its own—defiant of all paths and roads, piercing through the heart of every obstacle, and dragging living creatures of all classes, ages and degrees behind it” (Dickens 261). It is interesting that the accessibility of mass transportation is brought up as an additional reason for disdaining the train in Mr. Dombey’s mind. Earlier in the novel, he had sent Florence and Paul to Brighton with a carriage and had also used a carriage himself when visiting them. His use of the train is a shift away from the past. Not only is London and his family changing, but so is the way Mr. Dombey goes in and out of London.

The train transforms from a metaphorical death machine to a literal one with James Carker’s accident. When Mr. Dombey was on his way to Birmingham, the train was defined as a “monster,” a “remorseless” and “indomitable monster, Death!” (Dickens 261-2). Dickens’s tone in the passage leading up to Carker’s accidental death is much more sinister. If the train was an obvious iron death machine in the Birmingham passage, now it is a sly murderer, a predator quietly biding its time: “Death was on [Carker]. He was marked off from the living world, and going down into his grave” (Dickens 718). This change in the portrayal of death is partially to do with whose death is associated with the train. Paul’s death was tragic, while Carker’s death is not given the same courtesy. Carker is the biggest villain in the novel, and his death is described in the same, grim detail that one comes to expect from Dickens for his villains. Ironically, his last words in-text are, “Take away the candle. There’s day enough for me” (Dickens 717). Dickens accepts the ubiquity of industrial machinery; however, he does not welcome it with open arms. On the contrary, the gruesome death scene is almost a warning to remember the power of the new technology in the world. Carker’s death changes London by changing the Dombey family. Carker is responsible for a lot of misfortunes in the lives of the other characters, whether it be the downfall of Mr. Dombey’s firm, which eventually goes bankrupt “and the great House [is] down”; the deception of Captain Cuttle; or the mistreatment of Edith (Dickens 748). As a result, Dickens is able to highlight the significance of just one person in the makeup of London.

Change can be big or small. London changes with each railroad, and with each person. A huge change that is not as tangible in Dombey and Son is societal. Dickens constantly questions gender roles in Victorian England, most notably through the characters of Florence and Edith. Mr. Dombey treats the women in his life as inconsequential at best and often as though they were property. In the very first chapter while Paul is just a few minutes old, the reader is told the Dombeys “had been married ten years, and until this present day…he had no issue—To speak of; none worth mentioning. There had been a girl some six years before” (Dickens 6-7). Florence is an afterthought for Mr. Dombey; while son is always written with a capital “s,” girl is lowercase.

Mr. Dombey’s treatment of Edith is just as bad, and Edith knows this will be so before they get married. The night before her marriage to Mr. Dombey, she says to her mother, “You know he has bought me. Or that he will, tomorrow. He has considered of his bargain; he has shown it to his friend; he is even rather proud of it; he thinks that it will suit him, and may be had sufficiently cheap; and he will buy tomorrow” (Dickens 365). Edith knows she is a commodity in Mr. Dombey’s eyes and refers to herself as “it.” She criticizes the marriage market that denies women any agency, and later she decides to finally run away from her loveless marriage to Dijon, France with Carker. Dickens unequivocally takes Edith’s side. He shows his affection for Edith and her decisions, which is made evident by the fact that Edith loves Florence. Within the novel, the characters we are meant to root for all have a positive relationship with Florence. This is the case for Sol Gills, Captain Cuttle, Walter, and also for Edith. Another way Dickens favours Edith’s point of view is by going out of his way to mention that Edith did not have a relationship with Carker outside of her marriage so as to make sure she would remain sympathetic to a Victorian audience. This is additionally significant, because Edith’s decision to run away with Carker highlights the different opportunities for men and women to migrate within the text.

Edith has no say over her migration to London as she is essentially sold off to Mr. Dombey to be an obedient wife—the perfect angel in the house—and she is only able to leave by running away. Florence, likewise, tends to migrate with people. Firstly, she moves to Brighton with her brother, because her father wants her to. She is later left alone in the Dombey house and goes to China with Walter after they are married. The last case is when she has the most say over where she will live as her marriage is one based on mutual love.

Change begets change. In a city with so many people from so many different backgrounds and reasons to be there, it is no surprise that the one constant is that there is continuous change. In fact, Dickens’s London is defined by change; however, the way the city changes for different characters is affected by their gender and class.

*The trip to Camden is additionally the inciting incident for Florence to meet Walter Gay and is critical for the development of the subplot between the two characters.

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Murray. “Fictions of the City.” The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 106-119.

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Wordsworth, 1995.

Mullan, John. The Artful Dickens. Bloomsbury, 2020.

Waters, Catherine. “Gender, Family, and Domestic Ideology.” The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 120- 135.

This paper represents my own work in accordance with University regulations.

/s/ Kayra Guven

Monica Ali: a timeline

A timeline of Monica Ali’s life and career:

Monica Ali: photos

A map showing Tower Hamlets and Brick Lane/Google Maps

A map showing Tower Hamlets and Brick Lane/Google Maps

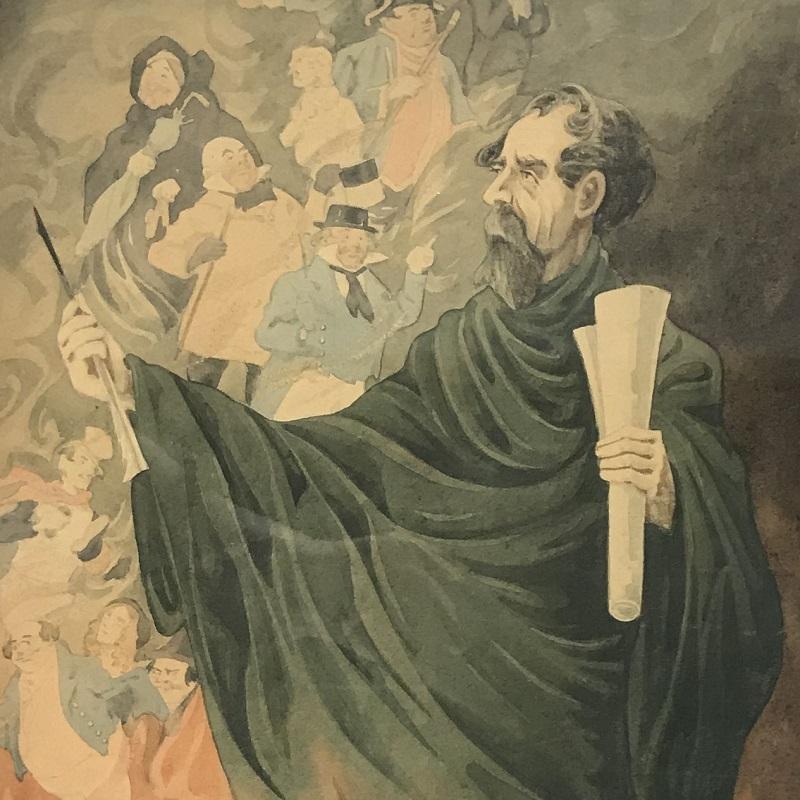

Charles Dickens: A Literary Life

Charles Dickens is one of the most influential literary figures of all time. He was an internationally bestselling author even while he was alive. He has written fourteen completed novels, a myriad of short stories, and even more newspaper articles. His works, imbued with social commentary, have raised awareness for socioeconomic injustices in Victorian Britain that were exacerbated by the Industrial Revolution. However, Dickens did not start off with the intention to become an author.

Before turning into the literary giant he is now known as, Dickens wanted to be an actor. He changed his mind, nonetheless, since he gained immense popularity very early in his writing career. His debut novel, The Pickwick Papers, which first issued in 1836, was a hit from the get-go. English professor John Mullan notes, “With Pickwick Papers, Dickens more or less invented the novel of monthly parts” (Introduction, The Artful Dickens).

The financial success of his serialized novels is particularly important, because Dickens grew up in a family that was constantly in financial trouble. His father, John Dickens, was sent to debtors’ prison when Charles was just twelve, leading him to work at a blacking factory as a child. This undoubtedly shaped Dickens’ attitude towards financial security. Dickens’ writing career, in turn, is both a result and a reflection of his experiences.

Steve McQueen: A Life in Pictures

Charles Dickens Image Gallery