Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway, pp. 60-61 (Penguin, 2012 edition):

“He sat down beside her, and couldn’t speak. Everything seemed to race past him; he just sat there, eating. And then half-way through dinner he made himself look across at Clarissa for the first time. She was talking to a young man on her right. He had a sudden revelation. ‘She will marry that man,’ he said to himself. He didn’t even know his name.

For of course it was that afternoon, that very afternoon, that Dalloway had come over; and Clarissa called him ‘Wickham’; that was the beginning of it all. Somebody had brought him over; and Clarissa got his name wrong. She introduced him to everybody as Wickham. At last he said ‘My name is Dalloway!’—that was his first view of Richard—a fair young man, rather awkward, sitting on a deck-chair, and blurting out ‘My name is Dalloway!’ Sally got hold of it; always after that she called him ‘My name is Dalloway!’

He was a prey to revelations at that time. This one—that she would marry Dalloway—was blinding—overwhelming at the moment. There was a sort of—how could he put it?—a sort of ease in her manner to him; something maternal; something gentle. They were talking about politics. All through dinner he tried to hear what they were saying.”

Through using free indirect discourse in Peter’s recollection of the day Clarissa met Richard Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s language mimics the pace and nature of Peter’s thoughts, allowing the reader to peek into his point of view despite the third person narration. From the perspective of someone who was at Bourton that day and did not have access to Peter’s mind, he appears to not care much for his environment as he barely moves and does not speak; however, since Woolf shows us Peter’s line of thought, we know that this expressionless exterior is a result of his inner conflict. This mute and immobile state is reflected in the punctuation. In the first sentence of the passage, there is a comma before “and couldn’t speak,” causing the reader to pause like Peter. Most of the sentences in the passage are fragmented by semicolons, dashes, and commas. Peter is nervous, because he is not aware of everything that is happening and is too afraid to do anything at that moment, and the punctuation emulates his emotions. It is almost as if he is trying to stop—or at the very least slow down—time through semicolons and dashes; however, he only manages to speed his perception of the passage of time by trying to slow down while everyone else is moving at normal speed. As a result, “everything seemed to race past him.” The rest of the first paragraph in the passage has no pauses within sentences as Peter is rushing to make up for lost time. The following two paragraphs, however, revert to using increasingly fragmented sentences as Peter gets more and more nervous. The inconsistent pacing from sentence to sentence is disorienting, and the reader is able to feel Peter’s discomfort.

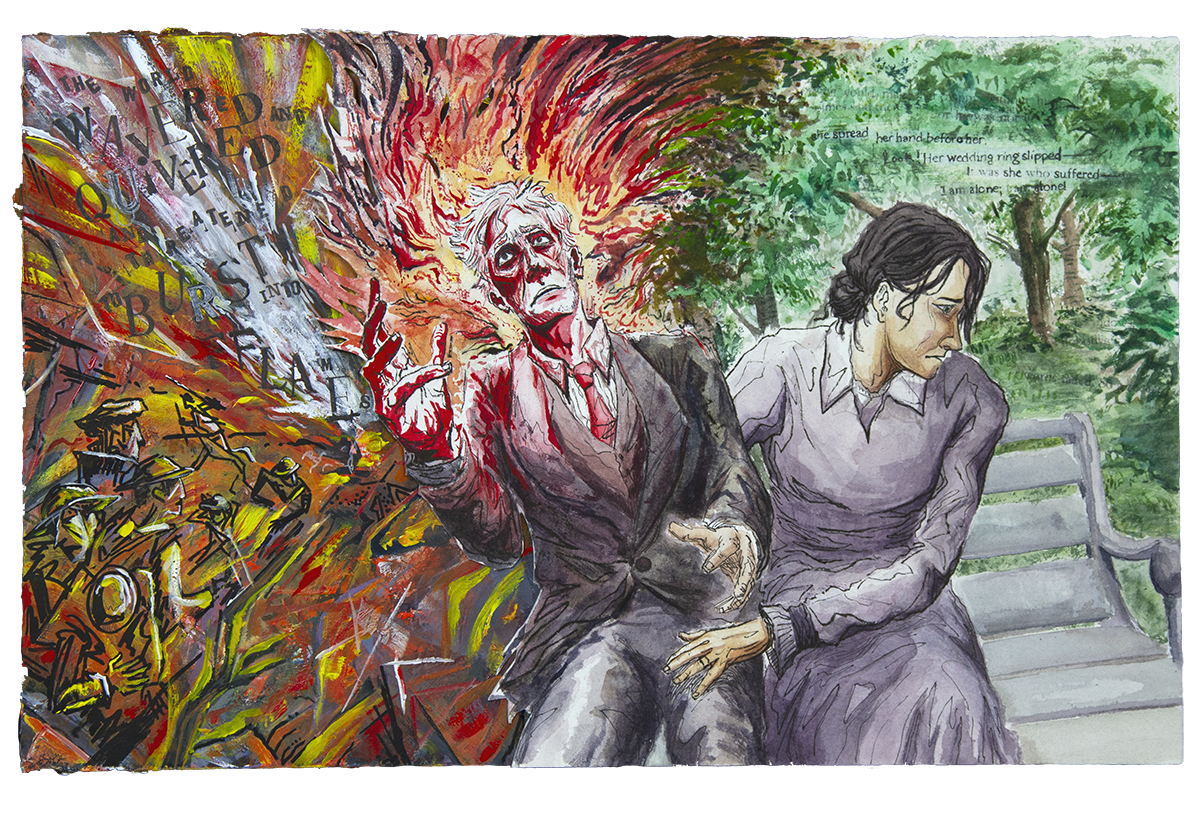

Peter’s anxiety comes from his limited viewpoint. He “sa[ys] to himself” that Clarissa will marry Richard, but he does not talk to Clarissa about this fear. When the narrator confirms Peter “didn’t even know [Richard’s] name,” we also understand from the use of the word “even” that this lack of knowledge frustrates Peter. He seems disappointed at how little he really knows Clarissa’s life. Here is this man who Clarissa will one day marry, and Peter does not even know his name. It is clear that Clarissa does not know Richard at this point either; however, Peter has a fatalistic tone that suggests he pinpoints the end of his potential relationship with Clarissa to this event. Despite being in the room, Peter is an outsider to Clarissa and Richard’s meeting. “All through dinner he tried to hear what they were saying,” meaning he was not actually able to listen. Again, there is that nervous tone exacerbated by the five dashes, two semicolons, and question mark used in the sentences leading up to this line. It makes sense that Peter cannot hear anybody else as he is too distracted by his own thoughts, leading to a myopic recounting of events.

The fragility of memory further complicates Peter’s recollection of the events of that day, making Peter an unreliable narrator. Peter superimposes his current thoughts into the past “for of course it was that afternoon, that very afternoon, that Dalloway had come over.” The addition of “of course” is Peter’s current thought. At the time, Richard was just some guy. However, Peter is having a hard time believing his luck in what he is recounting, which explains the desire to pretend all of his regrets were predestined. The incredulous tone is evident in the repetition of “that afternoon” with the addition of “very” for emphasis the second time around.

Peter’s relative insignificance to Clarissa is explored in Woolf’s allusion to Pride and Prejudice. Clarissa accidentally calls Richard “Wickham,” the charming yet deceitful soldier in Austen’s novel. In that case, is Clarissa Lydia? Or is she Elizabeth, disillusioned with Wickham’s character? Since she will eventually marry Richard Dalloway, it is tempting to say Clarissa is Lydia; however, Richard refuses his identity as Wickham by “blurting out ‘My name is Dalloway!’” He is described as “awkward,” and he shares Mr. Darcy’s pride and wealth. Nonetheless, it does not feel appropriate to compare Clarissa’s marriage to that of Lizzy’s, because there does not appear to be that similar happiness. Here, we see Woolf’s twist. In Mrs. Dalloway, Darcy is split into two characters: Richard and Sally. Pride and Prejudice makes it abundantly clear that Elizabeth Bennet is interested in Darcy because he makes her happy, but also because he is wealthy, and “to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!” (P&P, ch.43). Austen does not make her protagonist choose between security and happiness in the end. Woolf does. Clarissa’s kiss with Sally Seton is the happiest moment in all of her life, but Richard Dalloway provides a certain security that Sally could never. This leaves Peter as Mr. Collins. Earlier in the novel, Clarissa thinks to herself that she made the right choice marrying Richard as being in a relationship with Peter would have never worked, which parallels the relationship between Elizabeth and Mr. Collins.

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf talks about the importance of tradition and the want of a “common sentence ready for [women authors]” (ch.4). In Mrs. Dalloway, there is a deliberate evocation of women authors past, especially Austen (Woolf not only explicitly mentions Austen’s characters but also develops Austen’s frequent use of free indirect discourse in her own writing); this is a novel steeped in tradition. At the same time, there is a reinvention of tradition. In addition to Austen, Woolf is also reinventing the themes and styles of contemporary authors—most notably Joyce and Proust. The novel takes place over one day in June, like Joyce’s Ulysses. In addition, there are two protagonists, one of whom could be seen as a semi-autobiographical Woolf, akin to the relationship between Stephen Dedalus and Joyce. What is more, both novels depict the ordinary moments of life as beautiful and worthy of the same examination and reflection as the actions in epics. In this veneration for the daily, Mrs. Dalloway is also taking elements from Proust’s body of work. However, especially in this passage, Proust’s influence is most visible in the representation of memory as both fragile and sometimes involuntary. As a result of this simultaneous reinvention and preservation of tradition, Mrs. Dalloway becomes a bridge between the past and the present.