“Here he opened Shakespeare once more. That boy’s business of the intoxication of language—Antony and Cleopatra—had shriveled utterly. How Shakespeare loathed humanity—the putting on of clothes, the getting of children, the sordidity of the mouth and the belly! This was now revealed to Septimus; the message hidden in the beauty of the words. The secret signal which one generation passes, under disguise, to the next is loathing, hatred, despair. Dante the same. Aeschylus (translated) the same. There Rezia sat at the table trimming hats. She trimmed hats for Mrs. Filmer’s friends; she trimmed hats by the hour. She looked pale, mysterious, like a lily, drowned, under water, he thought.

“‘The English are so serious,’ she would say, putting her arms round Septimus, her cheek against his.

“Love between man and woman was repulsive to Shakespeare. The business of copulation was filth to him before the end. But, Rezia said, she must have children. They had been married five years.”

Mrs. Dalloway, 88-89

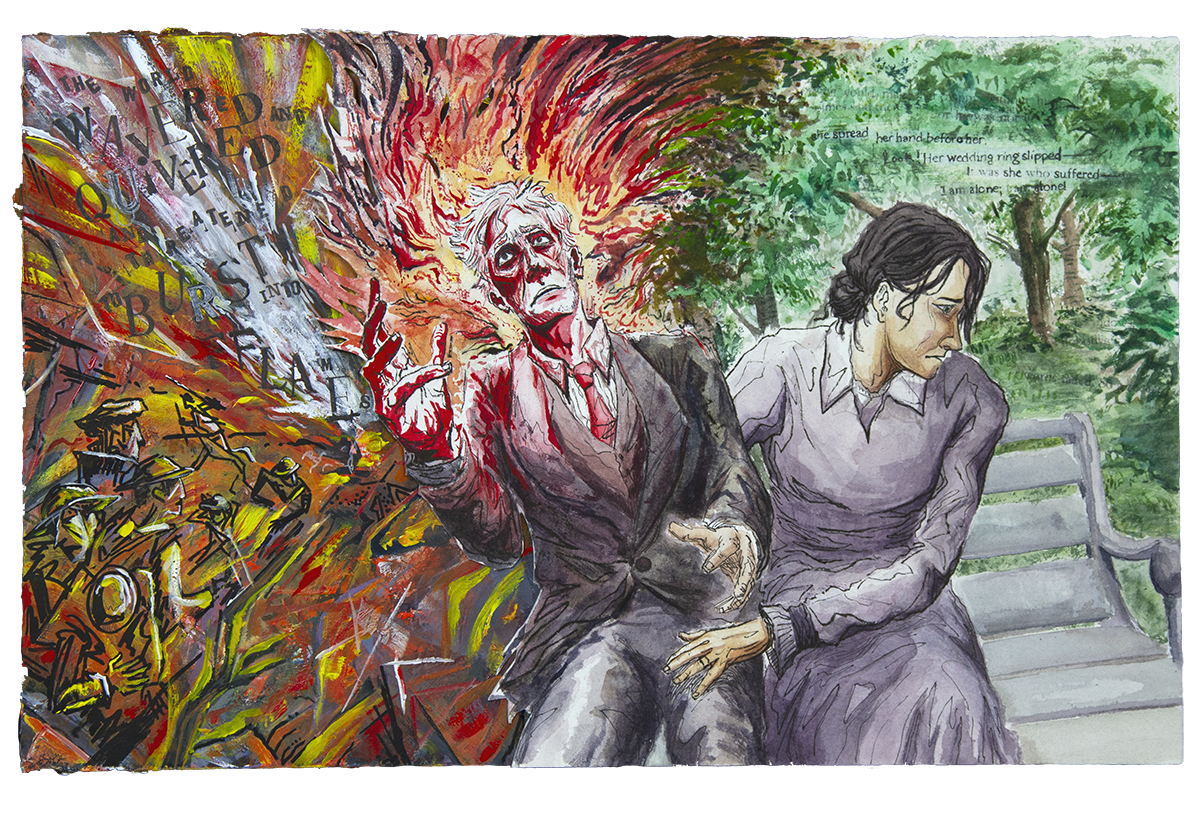

Woolf begins this passage with Septimus’s post-war reflection on Shakespeare. The passage takes place after Septimus’s return from the war with Rezia. The painting of Septimus’s earlier “intoxication” with Shakespeare’s language as “boy’s business” illustrates more than just the ending of a fascination or interest. The alliteration in “boy’s business” brings attention to it, gives it a name that sounds almost silly, that can be dismissed or condescended when read aloud. The use of the word “intoxication,” meanwhile, evokes a certain kind of sensuality. At this point, years after the war, the sensuality has “shriveled utterly.” Woolf’s language subtly tells her reader that while Septimus assures himself that he has matured or been enlightened—he has moved on from his “boy’s business”—what has really occurred is an absolute loss of sensation. Septimus points it out himself earlier on when he says he cannot feel anything. But it has seeped into his reading of plays that once intoxicated him, so the reader cannot necessarily trust Septimus’s readings.

Thus, when he remarks how “Shakespeare loathed humanity,” really it is Septimus who loathes humanity. Woolf piles up imagery for the reader to understand the depths to which Septimus can no longer feel, employing repetition of “the” to generate almost her own kind of assault on the reader’s senses. Septimus loathes “the putting on of clothes” because he can no longer feel the joy of nice fabric or the decorative properties of clothing; he loathes “the getting of children” because he no longer feels sexual excitement; he bemoans “the sordidity of the mouth and belly!” He takes no pleasure in the taste of food, and feels a disgust in the human body. The word “sordidity” employs repetition of sounds in itself, so the reader might understand that Septimus’s loss of feeling, the “shriveling,” is not so much the result of an extended lack of feeling, but the constant assault that has been placed on his senses while in the war.

Woolf repeats the word “trimming” three times when describing Septimus’s observations of Rezia. The effect is almost chant-like, or like a nursery rhyme, and reveals the way Septimus finds her actions silly, especially when compared to these great truths he believes to have uncovered, from none other than classic writers. Then he compares her to a “lily, drowned, under water.” This might be an allusion to Shakespeare, where Woolf Rezia equates Rezia to Ophelia from Hamlet. Hamlet, concerned with great issues of his father’s death and proper succession, rejects Ophelia. Septimus is thus like Hamlet; burdened with these great truths, or his own beliefs that the world’s “great signal” is of loathing, hatred, despair, Septimus rejects Rezia and avoids giving her children.

Woolf’s prose turns matter-of-fact as Septimus recounts an act of physical love from Rezia: how she puts her arms around him, “her cheek against his.” There is no sensation here, no stirring of emotion either positive or negative. One can practically see the coldness with which he responds, how he stiffens, utterly not at ease, as Rezia reaches out to him. Then the prose turns even colder, the sentences even shorter and straight to the point. “Love between man and woman was repulsive to Shakespeare. The business of copulation was filth to him before the end.” Shakespeare wrote comedies whose endings were marked with marriage. This is not Shakespeare’s opinion; it is Septimus’s. After all, the reader already knows Septimus regards the human body with disgust. How could he ever endure sex?

We’ve discussed at length in class the novel’s historical context as taking place after World War I, leading to discussions of shellshock and mental health in regard to Septimus. I think Woolf illustrates a really interesting understanding of trauma here, however, perhaps even ahead of her time. Today we understand that a characteristic of trauma and PTSD is the constant assault on a person’s nervous system, often triggered through sound or other sensory experiences that remind the victim of the traumatic event. Woolf’s prose, in its constant repetitions and almost bombarding Septimus with sensory experiences, might be trying to replicate the same feeling. In this way, the passage illustrates the ways in which literature can bring to life a phenomenon that might not yet be clinically understood.

Another intriguing historical context is of the novel as a post-pandemic work. Septimus’s aversion to touch, though primarily a symptom of his PTSD, feels incredibly fitting as a response to influenza. It is comparable to the social distancing we undertake in the COVID-19 era, and the near constant anxiety people feel when confronted with contact with another person’s body. The complete revulsion he feels toward the human body seems to have more to do with his general hatred of human existence; however, it would not be farfetched to think of it too as a disgust toward a physical being that carries disease.

Rezia’s character raises the question of women’s history here. I wonder whether she had different rights in England as an Italian immigrant, but either way, women’s suffrage was established in England following World War I. Septimus married her because she was the youngest of the sisters, because she was the “gayest,” perhaps because he thought her silly and unable to challenge him. I wonder whether we are meant to think of her assertion at the passage’s end—that “she must have children”—as a result of this era of women’s expanded liberty. Or is it more of a supplication?

Then, there is the literary context. We now know Woolf as an important voice in the British literary canon, but her inclusion of authors such as Shakespeare, Dante, and Aeschylus illustrates for her reader both what is regarded as a literary canon at the time, and how deeply she deviates from it. Aeschylus comes from Ancient Greece, Dante from the medieval era, and Shakespeare from Elizabethan England. They all wrote in verse and are regarded as important figures, whether in classics or medieval literature. Woolf’s writing, in its plunging into characters’ consciousness and unconventionally structured prose, is revolutionary against this literary backdrop.