Shakespeare looms large over Mrs Dalloway.

In the passage I selected, Septimus finds a justification for his attitude about life in the work of Shakespeare, even when this is only fiction that he has concocted himself.

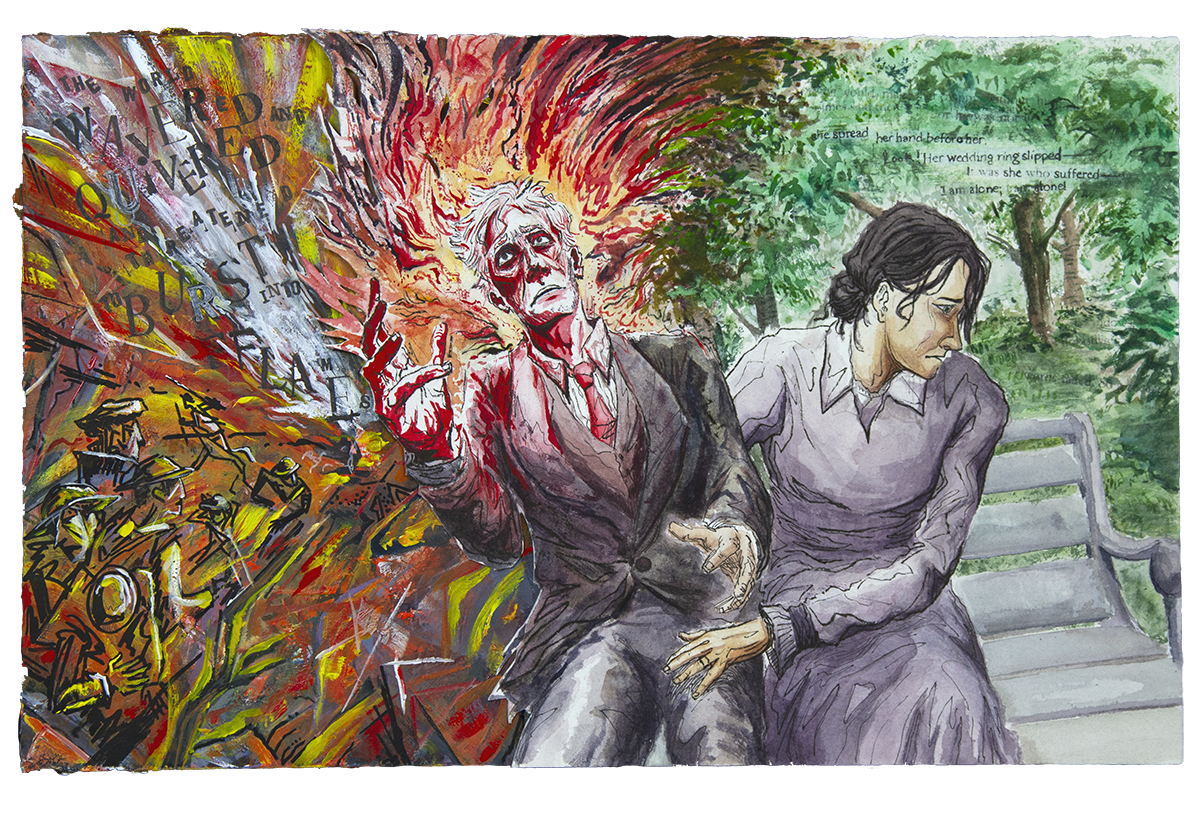

Shakespeare also draws the curtain between husband and wife: Rezia’s inability to read Shakespeare defines her as a stranger, at least in the eyes of Septimus. Ultimately, Septimus and Shakespeare become inseparable, veteran and soldier intertwined. Rezia even wonders if she will ever have a son like Septimus— in this case, Septimus is elevated to legend, just as Shakespeare had been. In fact, we are told that the war was in part fought in the name of Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s shadow also extends beyond this passage.

For instance, Clarissa Dalloway clings to Shakespeare’s words and draws her strongest motivation from them. And this begins early on. When we first encounter her, Mrs. Dalloway is haunted by memories of Peter Walsh, a scene reminiscent of Antony and Cleopatra.

Take the partying words of Antony and Cleopatra in the play:

Sir, you and I must part, but that’s not it.

Sir, you and I have loved, but there’s not it:

That you know well.

(The Complete Pelican Shakespeare, 1664, 86-89).

A version of those words becomes almost a refrain on the first page of Mrs. Dalloway. “Was that it?” Mrs. Dalloway asks herself again and again as she probes her memories, particularly those involving Peter Walsh. This comparison of the pair to perhaps the best-known lovers in literature means Clarissa and Peter were also once in love, but they were kept asunder by fate.

Mrs. Dalloway also rehashes another refrain from Shakespeare, which is even more potent than the first one:

Fear no more the heat o’ the sun

Nor the furious winter’s rages.

(Oxford World’s Classics, Mrs Dalloway, 11).

Whenever her anxiety mounts, Mrs. Dalloway turns to this phrase. “Fear no more,” she whispers to herself. This, it must be noted, is in complete opposition to Septimus’s interpretation of Shakespeare. Hers is one of hope; his of desperation. Yet both are referencing the same poet.

The relationship between Clarissa Dalloway and Sally Seton is also compared to the one between Othello and Desdemona. When Othello reunites with Desdemona early in the play, he breaks into extreme exaltation, declaring “if it were now to die ‘twere now to be most happy’, a line quoted in Mrs. Dalloway (44). This suggests Clarissa was also in love with Sally.

So Clarissa, like Shakespeare’s Antony, has many relationships—Sally, Peter, and tragically, Richard. And just like Antony, she ends up in the wrong marriage.

That is why I would argue Mrs. Dalloway is deeply influenced by Shakespeare’s tragedies. In fact, the novel can itself be considered a tragedy. This is achieved through the death of Septimus, which mimics Cleopatra’s.

In essence, Mrs. Dalloway is a novel of failed marriages. On a smaller scale, the passage I selected illustrates this point. Rezia and Septimus are unable to understand one another. This is attributed to their temperaments: the husband is cultured; the wife is practical. From this, we can also glean the gender disparities in society. The man can afford to study Shakespeare, while the woman is expected to undertake monotonous trimming. The husband can engage in abstraction as the wife worries about having children. We can also draw a distinction between the foreigner and the veteran citizen. Rezia is unable to understand Septimus and Shakespeare both. But on a larger scale, the dualities keep multiplying and they all echo Shakespeare. This leads me to further speculate that Septimus is supposed to be an archetype for English culture, a force as great as Shakespeare’s legend. Of course this legend was deeply scarred during the war. The mapping of Septimus’s insanity is then an act of disassociation of the English culture, a commentary on what should be kept and what should be left behind.