This essay represents my own work, in accordance with University regulations.

“It was as if she had woken one day to find that she had become a collector, guardian of a great archive of secrets, without the faintest knowledge of how she had gotten started or how her collection had grown. Perhaps, she considered, they just breed with each other. And then she imagined her secrets like a column of ants, appearing at first like a few negligible specks and turning so quickly into an unstoppable force” (228).

Introduction

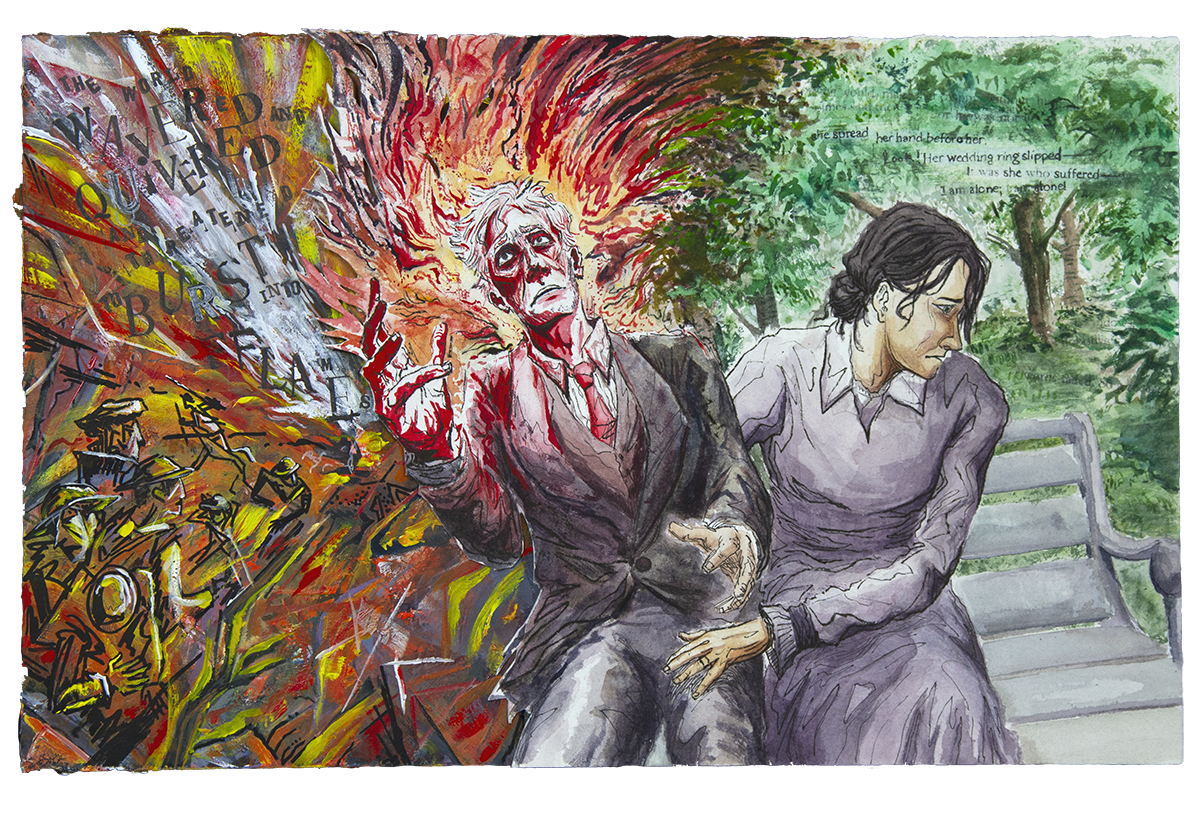

Unlike adventurous protagonists in the tradition of the realist novel such as Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, Nazneen is confined to the domestic arena and draws her power only from within. This is hinted at in the epigraphs announcing fate as the major theme of the novel. Because each of Nazneen’s attempts to forge into the outside world is considered a transgression in her society, she turns into a “guardian of a great archive of secrets”: her first walk in the city; her sister’s despair; her knowledge of Tariq’s descent into drugs, and most significantly the affair with Karim, are all secrets. While her husband, Chanu, conceals to abscond responsibility and soften his wounding humiliations, Nazneen uses secrecy to test the suffocating social boundaries around her before eventually breaking free from them.

As the secrets compound, the gulf between Nazneen and her husband widens, and by the end of the novel, the roles of husband and wife in the family have completely reversed. Secrecy allows Nazneen to ascertain her power and attain selfhood, sharpening her perception and allowing her to establish roots in the city, even as the marriage crumbles.

I: Quiet Rebellion

Mishra (2003) finds Chanu’s depiction is fuller than Nazneen’s. This is indeed a correct first impression. But if one takes Nazneen’s secrecy into account, she acquires a more complex interiority. In the first half of the novel, Nazneen’s secrets afford her a quiet rebellion, a profound rejoinder to Chanu’s hollow tirades.

While Chanu’s past is only one of glory, Nazneen’s is more nuanced. She clings to the legend of her nativity: Nazneen had been taught that she had survived her childhood only because she was surrendered to fate. Her mother, Amma, downplays the role she had played in nursing the daughter and instead attributes it to fate. This grants the child freedom from life’s drudgery and banishes all ambition. For a woman, the desire for self-improvement is itself considered a sin. But Nazneen’s life is nothing but toil: she submits to her father, who marries her off to Chanu. And at her house, she essentially becomes a maid, tending only to Chanu’s needs: she cuts his corns and trims his nails. Because there is no satisfaction in such humiliating work, Nazneen falls back into her mother’s philosophy: she surrenders to fate, which justifies the toil and gives her a different source of purpose, a purpose she may have found in a job of her own. Unrooted and displaced in London, Nazneen grounds herself in tradition. She draws resilience from the conviction that there is nothing she can do about her life. “What could not be changed must be born,” was how Amma had put it (p. 4). But the toil becomes too unbearable for Nazneen and she quietly rebels. These transgressions gather into secrets.

When Jorina, a woman in the neighborhood, commits suicide, Nazneen is concerned. The news is broken by Mrs. Islam, whose authority over the neighborhood rests solely on her archive of secrets. For women, secrecy is a source of power. This is made more explicit when Nazneen inquires about why Jorina had killed herself. “You can hardly keep it a secret when you begin going out to work,” Razia theorizes (p. 13). The woman’s sin, it turns out, was that she had found a job for herself. This piques Nazneen’s curiosity. She formulates a question about Jorina’s death, rephrasing it endlessly, but she never gathers enough courage to pose it to Chanu. This sets the ground for her rebellion.

When Nazneen accompanies Chanu to Dr. Azad’s practice, he introduces her as “shy”, but she locks eyes with the doctor, finding herself “caught in a complicity of looks” (p. 19), which threatens to give off what her husband is not saying. Although she has no role in the conversation, she still manages to tip Chanu off. Nazneen also represses her desire to act, secretly hatching plans in her head, which compensate for her passivity. “She wanted to get up from the table and walk out of the door and never see [Chanu] again” (p. 18). So forceful is her desire for rebellion even when she is completely subdued.

Nazneen’s first true transgression is the walk she makes to the city by herself, unaccompanied by her husband. This journey represents independence. Chanu confines her to the house, locked from the outside world. Embarrassed, he also hides the details of his job from Nazneen. He wants to live with her in the same house but still somehow maintain a distance, keeping the assaults against his manhood only to himself. Even in his ramblings, Chanu manages to remain obscure, rarely briefing Nazneen on the true contents of the books he reads, claiming that they are not easy to translate. This forces Nazneen to forge into the city on her own. And when she takes the walk to the city and makes it back to her house safely, having asked for directions, this cements Nazneen’s power and bolsters her self-confidence. “See what I can do,” she says to herself, addressing Chanu, although she cannot yet summon the courage to tell him about the walk (p. 40). At least she discovers she no longer has to rely on him. And this must be kept a secret: he wields too much power over. If Nazneen confesses her transgression, Chanu may restrain her and this is not a risk she is ready to take.

But Nazneen finds a different outlet for action. Her sister, Hasina, writes to her from home to tell her that she had escaped from her husband to Dhaka. This is Hasina’s secret and no one in the village knows about it. Nazneen is convinced her sister’s action will put her in great peril. “Once you get talked about, then that’s it,” she confirms (p.38). A woman is only safe as long as she remains servile to her husband; if she breaks free, that is the end for her, as has been the case of Jorina. Nazneen is worried such a fate is awaiting her sister and she appeals to Chanu for action. But Chanu downplays the sister’s case and instead sympathizes with the husband, whom Hasina had confessed had brutally beaten her. “What will happen will happen,” Chanu says, echoing Amma’s philosophy of submission to fate. Nazneen feels betrayed and withholds Hasina’s future letters from her husband. This, she believes, is a case she must take up on her own. For the first time, she punishes Chanu for the grievance. She stops praying for his promotion, puts “fiery chilies’ into his sandwich, slips the razor when cutting his corns, and registers her rebellion in all the chores she undertakes (p. 40). But Chanu barely notices Nazneen’s discontent. If anything, he suppresses her even more. For instance, when Nazneen suggests enrolling in Razia’s college, Chanu feigns indifference (p. 51). This confirms to her that she cannot rely on him for anything. Nazneen must rebel more fiercely.

II: The Affair

Walter (2003) finds fault with Hasina’s letters, writing, “I don’t quite understand why Hasina’s letters are written in such broken prose, since presumably she would write in her own language”. This ignores the fact that spelling mistakes can also occur in the Bengali language. But the true distinction between the sisters is one of temperament. Nazneen admires Hasina’s broken spelling and finds her correspondence more lively than her own letters, which are anguished and forever in search of perfection. Gorra (2003) lucidly captures the true intention of Hasina’s letters. “Hasina’s account of her life in a desperately poor city [tells] Nazneen that the “home” she imagines no longer exists,” he writes.

Hasina’s desperation is clearly overstated. Mishra (2003) points out that Hasina “sounds more like a travel writer from England than an oppressed Bangladeshi woman”. However, there is no doubt that Hasina’s grim experience back home alleviates Nazneen’s nostalgia and grounds her in the city. This is a secret she withholds from the tormented Chanu, until later in the novel. But her sister’s correspondence is not enough solace for Nazneen. The “external three-way torture of daughter-father-daughter” becomes too unbearable for her (p. 147).

This slowly leads to Nazneen’s biggest secret. Estranged from her husband, Nazneen begins dreaming of finding a job for herself and sending money to Hasina (p. 133). She swings into action and masters “basting, stitching, hemming, buttonholing and gathering” (p. 139). In this way, she invents a job for herself without leaving the house, as Jorina had been forced to do. At this point, Nazneen also finds out that Chanu had taken a loan from Mrs. Islam and she confronts him about it. As always, he merely ignores her. But when Nazneen starts working at home, Chanu does not ask her to stop; instead, the roles of wife and husband reverse and he begins helping her, “passing scissors, dispensing advice, making tea, folding garments (p. 147.” He desperately wants to be in charge, even calculating the profit margins on her behalf. Chanu is unmotivated and he has given up his big ambitions. He has essentially resigned to fate. “Now, I just take the money, I say thank you. I count it,” he says (p. 154). This sense of despair bothers Nazneem and she desperately wants an escape.

This is when Nazneen falls for Karim, the middleman who brings her the garments. Unlike Chanu, Karim is a man of action; in fact, his favorite catchphrase is “man”. Though he is of the same generation as Tariq, Karim is different. Where Tariq steals from his mother (saying “Ok-Mama” to everything she says) and succumbs to drugs (a secret Nazneen picks on early but never discloses to Razia), Karim rebels from his parents and loathes them intensely. He scolds his father for spending too much money calling back home and faults him for growing passive after decades of driving. Karim just cannot stand weakness and this attracts Nazneen to him.

In Nazneen’s eyes, Karim accounts for Chanu’s weaknesses: he is confident and knows his place in the world. And he gives her the attention she needs. Being an Islamic activist, Karim brings Nazneen leaflets and slowly radicalizes her. This allows her to avenge Chanu for a lifetime’s grievances. “You are not the only one who knows things,” she would retort, secretly and only to herself (p. 176). But Chanu still remains indifferent, even oblivious. Threatened by the leaflets, he finds mistakes in them, claiming they give “a wrong impression of Muslims” (p. 188), though he is himself not a practicing Muslim. But this does not discourage Nazneen. The secrecy of her affair with Karim and the possibility of Chanu finding out only intensifies her desire (p. 188).

The affair permits Nazneen to break free from the philosophy that she had inherited from her mother (and subsequently Chanu) and grants her urgency, almost instantly. “For a glorious moment,” we are told, “it was clear that clothes, not fate, made her” (p. 201). This allows her to bridge the barrier between her and Karim, while at the same time drawing closer to her daughters, who are of the same generation. And as soon as Chanu alienates Shahana by calling her memsahib and addressing her through her younger sister, Bibi, she begins confiding in Nazneen. The immensity of the transgression (considered to be the biggest sin in Islam) endows Nazneen with a fearlessness she had never known before. The city also justifies her action: Nazneen overhears the “rhythmic knocking” from the bed of her next-door neighbor, who drops one new boyfriend after another, and this allows her to view her own affair as nothing out of the ordinary (p. 221).

III: The Epiphany

After the affair, Nazneen changes and begins to use her power: she stands up to Mrs. Islam, who had been bullying her with her two sons for a long time; she breaks up with Karim after realizing he is not the man she had imagined him to be, and she refuses to return back home with Chanu when he acquires the tickets. These are all out of sync with Nazneen’s temperament in most of the novel. The secrecy takes on an outward force, which surprises the reader. Yet, even when she awakens, Nazneen still lacks a strong conviction. Though she refuses to return home, she does not entirely abandon Chanu and one can imagine her sending money to him.

Therefore, Brick Lane leaves loose ends. For instance, no reason is provided for why Nazneen does not tell Razia about Tariq’s descent into drugs, although the two are close friends. And the epiphany about Karim comes too suddenly. Moreover, the relationship between Chanu and Nazneen continues to linger on. These moments can all be seen as an extension of Nazneen’s passivity. Hiddleston (2005) argues that the novel operates on “shapes and shadows”, playing with “provisional forms, rather than determinate individuals or incontrovertible truths” (Hiddleston, 71). In a sense, the novel is itself cast as fate, unrooted, uncertain of itself. It becomes a secret to unravel. This hesitancy in the narration is one Ali herself confesses in a 2003 essay in The Guardian. “Standing neither behind a closed door, nor in the thick of things, but rather in the shadow of the doorway, is a good place from which to observe,” she writes. But I am convinced that these are just the faults of a debut novel. Although Nazneen’s epiphany comes too late and lasts only briefly, I think this force can be gleaned even in the early pages if one pays attention to her power for secrecy.

Conclusion

Nazneen’s power gathers slowly, almost like an army of ants, and this is driven by her talent for secrecy. These secrets allow Nazneen to transcend the social boundaries and eventually take control of her fate. But the journey to this moment is too slow and it comes too swiftly, which necessitates close attention to detail, particularly the secrets.

Bibliography:

Hiddleston J. Shapes and Shadows: (Un)veiling the Immigrant in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 2005;40(1):57-72. doi:10.1177/0021989405050665

Micheal Gorra, “East Enders”, The New York Times, September 7 2003. Available here.

Monica Ali, Brick Lane. New York: Scribner, 2003.

————— “Where I am Coming From”, The Guardian, June 17 2003. Available here.

Natasha Walter, “Citrus Scent of Inexorable Desire”, The Guardian, June 14 2003. Available here.

Pankaj Mishra, “Enigmas of Arrival”, The New York Review of Books, December 18 2003. Available here.

A map showing Tower Hamlets and Brick Lane/Google Maps

A map showing Tower Hamlets and Brick Lane/Google Maps