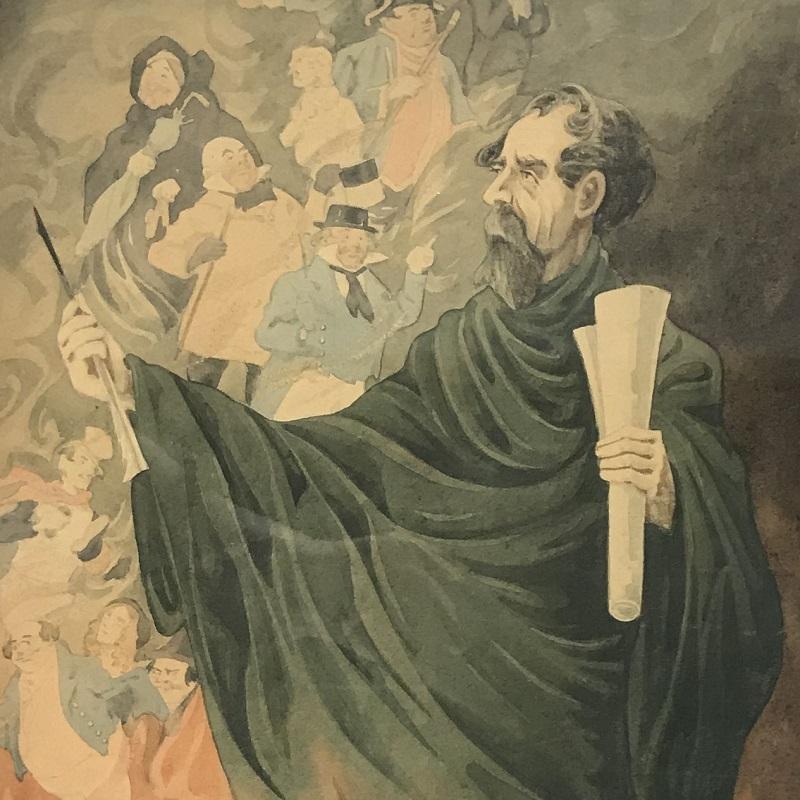

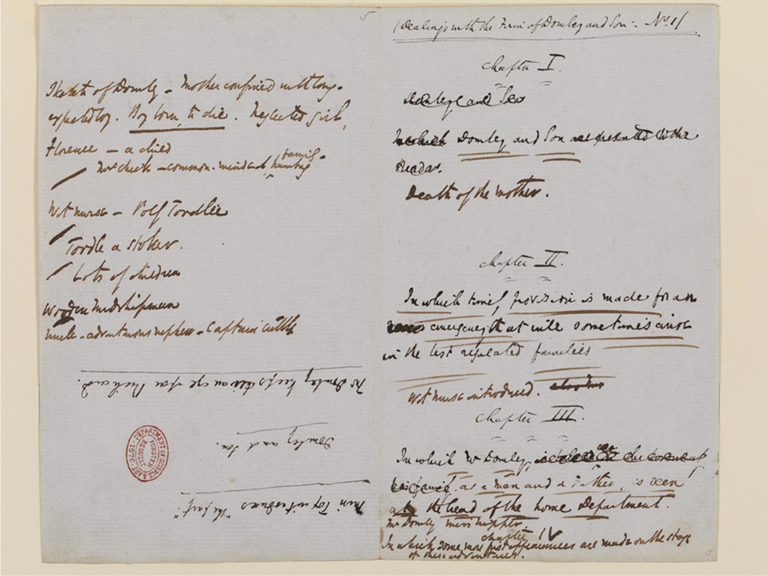

The world is ever-changing, and London in the 1840s was changing more rapidly than most places in most time periods. Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens is a novel trying to come to terms with this change. It is a novel with one foot in the past and the other in the present, exploring post-industrial life with its new technology, new business, and new society. There is an element of uncertainty that comes with change, and Dickens examines the effects of these uncertainties through his multigenerational account of the Dombey family. Professor of Victorian Literature Catherine Waters notes, “Dombey and Son marks the beginning of Dickens’s engagement with the family as a complex cultural construct, exploring the connections between familial and economic relations” (127-8). As a result, the family is a reflection of the society in which it lives and likewise constantly changing, because in Dombey and Son, London is defined by change.

Trains and railways mark the death of an earlier London in Dombey and Son and also function as markers for significant changes for the life of the Dombeys. Professor of English and founding director of The Dickens Project Murray Baumgarten writes, “Dickens understood that his was a world in transition, and that it was defined not just by the modern habits it was moving toward but the traditional habits it was leaving behind” (111). Perhaps no passage exemplifies this transition as vividly as the description of Camden Town early in the novel when Polly Toodle is taking Paul, Florence, and Susan with her to visit her home.* “The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre” (Dickens 63). Dickens has not yet revealed what is causing this commotion, but whatever it might be is clearly unsettling and devastating, like an earthquake. Before the reader has the opportunity to find their bearings, the setting is introduced by recounting how the ground feels—shaking—followed by the horrifying visual companion: “Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped…Here, a chaos of carts, overthrown and jumbled together, lay topsy-turvy at the bottom of a steep unnatural hill” (Dickens 63). The moment that is supposed to be a homecoming for Polly is interrupted by chaos—she cannot return to the Camden that she knew—and suspense is built as the description continues. The reader does not know what has happened here, but it is worse than an earthquake, because this is an “unnatural” and intentional disaster.

That the damage is a by-product of construction work is particularly jarring due to the juxtaposition of the detailed description of destruction with the curt reveal. “In short, the yet unfinished and unopened railroad was in progress; and, from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilization and improvement” (Dickens 63). This one sentence is a paragraph onto itself following the longest paragraph in the chapter with its lofty sentences dedicated to unpacking the specific consequences of industrialization in a community. The sudden change in tone matches the visual contrast on the page. Dickens is mocking the idea of linear progress. He does not think continuing to build suspense is worth the mundane reveal, which creates an impatient and dismissive tone. “In short,” the reader surely knows what is going on: the railways are championing modernity; they are the vanguard of progress. Dickens is playing with the common image of industrialization as “mighty” and an unambiguous sign of “civilization and improvement” by showing the “dire disorder” that the railway leaves behind.

There is implicit class critique in Dickens’s portrayal given that the construction affects the neighbourhood of little Paul Dombey’s nurse. It is almost impossible to imagine a similar situation occurring near Mr. Dombey’s mansion “on the shady side of a tall, dark, dreadfully genteel street in the region between Portland Place and Bryanstone Square” (Dickens 24). Camden is in contrast with the quieter, wealthier Dombey neighbourhood, and this dichotomy is played up to an extreme level later when Florence is separated from Susan and the rest of her group because of a mad bull. What is more, Polly is as shocked by the railway as the rest of her group, highlighting the fact that she has been away from her family and home due to the demands of her job. It is almost as if she moved to a different city and not a different place within the same city. The text does not let the reader forget Polly’s job by referring to her as “Richards,” the name given to Polly by Mr. Dombey (Dickens 63). Professor of English John Mullan observes, “The renaming is so wonderfully unnecessary—such a foolish assertion of power” (135). In addition, the renaming further distances Polly from her family. The railway, like Polly’s new work name marks change.

Another critical moment in the plot that both signifies a change for the Dombey family and London is Mr. Dombey’s train ride to Birmingham. Little Paul—the Son in Dombey and Son—is dead, and the train is leading Mr. Dombey to his soon-to-be second wife, Edith. Understandably, the tone is much more morbid than the description of the construction at Camden. Mr. Dombey “found no pleasure or relief in the journey,” because he is grieving, and the train comes to symbolize death (Dickens 261). Even though Dickens had already written about the damage caused by the construction, his tone was slightly more playful then. Now, “the very speed at which the train was whirled along, mocked the swift course of the young life that had been borne away so steadily and so inexorably to its foredoomed end” (Dickens 261). Dickens is serious, angry even, because Mr. Dombey’s emotions overshadow all else. The train is a death machine “that forced itself upon its iron way—its own—defiant of all paths and roads, piercing through the heart of every obstacle, and dragging living creatures of all classes, ages and degrees behind it” (Dickens 261). It is interesting that the accessibility of mass transportation is brought up as an additional reason for disdaining the train in Mr. Dombey’s mind. Earlier in the novel, he had sent Florence and Paul to Brighton with a carriage and had also used a carriage himself when visiting them. His use of the train is a shift away from the past. Not only is London and his family changing, but so is the way Mr. Dombey goes in and out of London.

The train transforms from a metaphorical death machine to a literal one with James Carker’s accident. When Mr. Dombey was on his way to Birmingham, the train was defined as a “monster,” a “remorseless” and “indomitable monster, Death!” (Dickens 261-2). Dickens’s tone in the passage leading up to Carker’s accidental death is much more sinister. If the train was an obvious iron death machine in the Birmingham passage, now it is a sly murderer, a predator quietly biding its time: “Death was on [Carker]. He was marked off from the living world, and going down into his grave” (Dickens 718). This change in the portrayal of death is partially to do with whose death is associated with the train. Paul’s death was tragic, while Carker’s death is not given the same courtesy. Carker is the biggest villain in the novel, and his death is described in the same, grim detail that one comes to expect from Dickens for his villains. Ironically, his last words in-text are, “Take away the candle. There’s day enough for me” (Dickens 717). Dickens accepts the ubiquity of industrial machinery; however, he does not welcome it with open arms. On the contrary, the gruesome death scene is almost a warning to remember the power of the new technology in the world. Carker’s death changes London by changing the Dombey family. Carker is responsible for a lot of misfortunes in the lives of the other characters, whether it be the downfall of Mr. Dombey’s firm, which eventually goes bankrupt “and the great House [is] down”; the deception of Captain Cuttle; or the mistreatment of Edith (Dickens 748). As a result, Dickens is able to highlight the significance of just one person in the makeup of London.

Change can be big or small. London changes with each railroad, and with each person. A huge change that is not as tangible in Dombey and Son is societal. Dickens constantly questions gender roles in Victorian England, most notably through the characters of Florence and Edith. Mr. Dombey treats the women in his life as inconsequential at best and often as though they were property. In the very first chapter while Paul is just a few minutes old, the reader is told the Dombeys “had been married ten years, and until this present day…he had no issue—To speak of; none worth mentioning. There had been a girl some six years before” (Dickens 6-7). Florence is an afterthought for Mr. Dombey; while son is always written with a capital “s,” girl is lowercase.

Mr. Dombey’s treatment of Edith is just as bad, and Edith knows this will be so before they get married. The night before her marriage to Mr. Dombey, she says to her mother, “You know he has bought me. Or that he will, tomorrow. He has considered of his bargain; he has shown it to his friend; he is even rather proud of it; he thinks that it will suit him, and may be had sufficiently cheap; and he will buy tomorrow” (Dickens 365). Edith knows she is a commodity in Mr. Dombey’s eyes and refers to herself as “it.” She criticizes the marriage market that denies women any agency, and later she decides to finally run away from her loveless marriage to Dijon, France with Carker. Dickens unequivocally takes Edith’s side. He shows his affection for Edith and her decisions, which is made evident by the fact that Edith loves Florence. Within the novel, the characters we are meant to root for all have a positive relationship with Florence. This is the case for Sol Gills, Captain Cuttle, Walter, and also for Edith. Another way Dickens favours Edith’s point of view is by going out of his way to mention that Edith did not have a relationship with Carker outside of her marriage so as to make sure she would remain sympathetic to a Victorian audience. This is additionally significant, because Edith’s decision to run away with Carker highlights the different opportunities for men and women to migrate within the text.

Edith has no say over her migration to London as she is essentially sold off to Mr. Dombey to be an obedient wife—the perfect angel in the house—and she is only able to leave by running away. Florence, likewise, tends to migrate with people. Firstly, she moves to Brighton with her brother, because her father wants her to. She is later left alone in the Dombey house and goes to China with Walter after they are married. The last case is when she has the most say over where she will live as her marriage is one based on mutual love.

Change begets change. In a city with so many people from so many different backgrounds and reasons to be there, it is no surprise that the one constant is that there is continuous change. In fact, Dickens’s London is defined by change; however, the way the city changes for different characters is affected by their gender and class.

*The trip to Camden is additionally the inciting incident for Florence to meet Walter Gay and is critical for the development of the subplot between the two characters.

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Murray. “Fictions of the City.” The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 106-119.

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Wordsworth, 1995.

Mullan, John. The Artful Dickens. Bloomsbury, 2020.

Waters, Catherine. “Gender, Family, and Domestic Ideology.” The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 120- 135.

This paper represents my own work in accordance with University regulations.

/s/ Kayra Guven