In his five-film anthology series Small Axe, Steve McQueen explores the varied dimensions of Black British life, particularly within Caribbean immigrant communities in the city from the late 1960s through the 1980s. In Mangrove, the first film, McQueen depicts the story behind the Mangrove Nine, a group of Caribbean immigrants living in Notting Hill who were harassed by police and arrested after staging a protest. McQueen centers the film on the Mangrove restaurant as a physical and figurative representation of how the characters’ shared Caribbean heritage shapes their experiences in London. Over the course of the film, McQueen traces the Mangrove’s evolution into the political center of the story.

McQueen opens the film with an overhead shot of Notting Hill, following Frank across the neighborhood. As Frank walks along the streets, the sound transitions from the ambient din of the city into Bob Marley & The Wailers’ “Try Me.” As the viewer sees the setting in which the film will take place, McQueen juxtaposes the sights and sounds of London—playing children, construction projects, and more—with the Caribbean influences that shape Notting Hill. Adding to this effect, layered over the music, Darcus Howe (another member of the Mangrove Nine whom the viewer will meet later) reads the words of C.L.R. James: “These are new men. New types of human beings. It is in them that are to be found all the traditional virtues of the English nation, not in decay as they are in official society, but in full flower. Because these men have perspective. Note particularly that they glory in the struggle. They are not demoralized or defeated or despairing persons. They are leaders, but are rooted deep among those they lead.” The scene ends with Frank arriving at the central site of the film: the Mangrove restaurant (0:01:00-0:02:48). With this opening scene, McQueen introduces the viewer to the key issue of the story: the Mangrove as a political community space. While Frank is hesitant to recognize it as such at first, this first scene shows that politics inherently inflects Notting Hill because it is a Black immigrant community. C.L.R. James’s quotation emphasizes this point. James was a Trinidadian historian who was pivotal in calling attention to the revolutionary struggles in Haiti and elsewhere in the Caribbean. These lines foreshadow the action of the film. By positioning the camera on Frank as Darcus reads the words, McQueen implicitly presents Frank as one of these “leaders,” and depicts the community in which he is “rooted.” McQueen also sets up an argument that the “traditional values of the English nation” lie with these “new men,” Caribbean immigrants like Frank, rather than in “official society.” In the police brutality and trial to come, the viewer will have the opportunity to judge for themselves which side embodies these values. Thus, McQueen opens the film by positioning the Mangrove as a community space, and a latent political space.

In addition to C.L.R. James, McQueen highlights other Caribbean activists alongside important moments at the Mangrove. After the police first violently raid the restaurant, the scene cuts from Frank resisting the officers to a poster of Paul Bogle on the restaurant’s wall (0:18:50-0:19:03). Bogle was a leader of the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica, in which Black Jamaicans protested economic inequality in the post-emancipation society. Thus, although Frank has not explicitly linked himself or the Mangrove to a larger political movement to challenge police power, McQueen’s directorial choices highlight that the resistance Frank is waging is still connected to a lineage of Black Caribbean resistance. The poster is also shown in the background of the scene in which Althea offers Frank the Black Panthers’ support (0:19:30-0:19-56). Frank at first fears making more trouble by having the Mangrove serve as a space for political activism, telling Althea that the Mangrove is “a restaurant not a battleground.” But he agrees to let the Panthers meet at the Mangrove if Althea plays in the Mangrove steel band at the carnival (0:20:32-0:21:50). Thus, the Mangrove begins to shift from being a community space into a political space.

McQueen further conveys the interconnectedness between the Mangrove as shared community space and as activist space through his filming of the police second raid of the restaurant. This time, the camera takes on Frank’s perspective and the viewer sees through his eyes. The camera sits at floor level, where Frank lies after being tackled, and the viewer sees a colander fall to the ground after an officer knocked it down. The scene stays silent for thirty seconds until the colander stops rocking (0:28:20-0:29:30). Through McQueen’s directorial device, the viewer sees that the Mangrove cannot just exist as a restaurant and gathering space; the police see it as a political space, a political threat, and thus the people of Notting Hill must protect it through activism. By putting the viewer in Frank’s place, McQueen compels them to consider Frank’s point of view, literally and figuratively. This allows the viewer to understand his eventual agreement to participate in protest.

The second poster McQueen uses to highlight the latent political potential of the Mangrove comes again juxtaposed between police brutality and Frank’s increasing openness to political action. After a scene in which Frank intervenes in a stop and frisk, McQueen’s camera lingers on a poster of Jean-Jacques Dessalines at the Mangrove, while Darcus tries to convince Frank to hold a march (0:40:55-0:41:07). Dessalines was one of the most important generals in the Haitian Revolution and the author of the Haitian Declaration of Independence as well as its 1805 Constitution. Darcus also alludes to the unfolding Trinidadian revolution when persuading Frank. Thus, McQueen highlights through visualization and dialogue the way in which Caribbean revolutions influence the characters. Demonstrating this further, Darcus repeats the C.L.R. James line that opened the film, this time explicitly identifying Frank as the leader rooted deep among those he leads. Darcus says he sees Frank as a man “of great patience and humility who unbeknownst to him has become” this leader (0:42:44-0:43:23). But while Darcus—and through McQueen’s direction, the viewer—sees a direct tie between the revolutionary politics of the Caribbean and the need for action here in London, Frank is more hesitant, telling Darcus, “We’re not in Trinidad now, boy. This is Notting Hill.” Darcus, however, sees that as all the more reason to protest. He argues that Frank must assert the Mangrove, and by extension Black Caribbean immigrants, as having a right to exist in Notting Hill. “This place, the Mangrove, it is Notting Hill,” Darcus implores Frank. The Mangrove’s importance as a community space necessitates political action in Darcus’s view, as he tells Frank that “this is community, the Black community is your community. The Black community who rely on the Mangrove just as much as you rely on them. Take it to the street” (0:43:37-0:44:03). Darcus insists that Frank has a duty to fight back against police brutality because the Mangrove is so central to the Caribbean community in Notting Hill. Thus, the Mangrove’s status as a community space for Black immigrants makes it a locus for political activism as well.

Darcus’s closing statement at the Mangrove Nine’s trial further shows the Mangrove’s evolution into a political space. He starts by recounting how the Mangrove came to be, stating that “in defending themselves against attack” by the police, “a community [was] born” in Notting Hill. “And wherever a community is born, it creates institutions that it needs.” The Mangrove became such an institution not by design, but by circumstance. Frank did not intend for the Mangrove to be the political community space that it became, but Darcus argues that this eventuality was inevitable: “But that sense of community, born out of struggle in Notting Hill, was so profound that there was no other way for it to be but a community restaurant. We created the Mangrove. We shaped it. We formed it to satisfy our needs! The Mangrove is ours. It is ours, it’s not Frank’s! He lost it to the community, he knows that.” (1:54:11-1:54:33). Here, Darcus extends his logic from his earlier conversation with Frank, articulating how a “community restaurant” is inherently political when “born out of struggle.” More than just serving Notting Hill’s Caribbean immigrants the food they recall from their homelands, the Mangrove served as an institution for community organizing and coalition building. As Darcus says, activists “formed” the Mangrove “to satisfy [their needs],” including being a space for political activism. Thus the Mangrove was bigger than just Frank’s restaurant—it was the community’s restaurant. In the film, then, it represents the political capacity of London’s Caribbean community, acting as a symbol for the struggles and achievements they experienced.

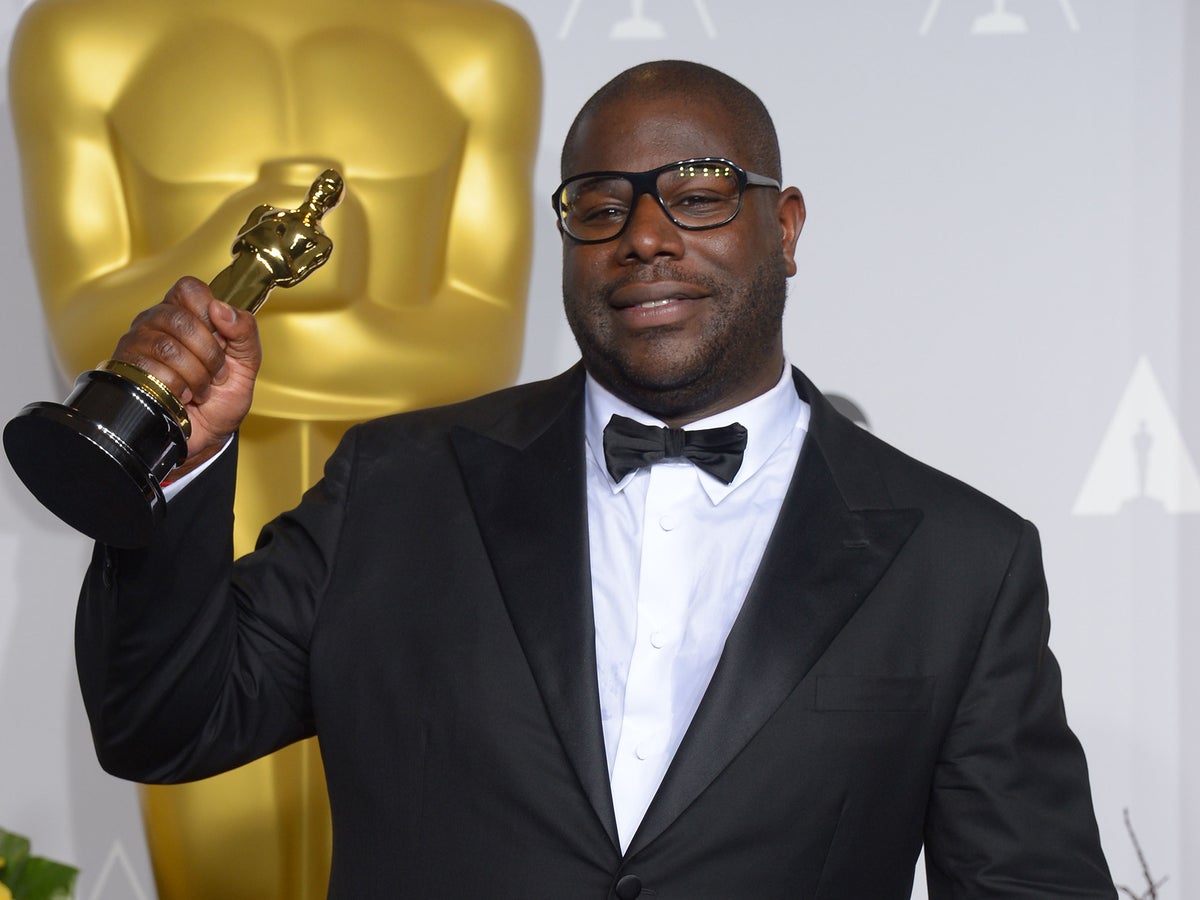

Immigration shapes every aspect of Mangrove, as the characters’ shared cultural backgrounds bring them together around the Mangrove restaurant and tie them to one another through the discrimination they face. To visualize the importance of immigration to his story, McQueen uses a number of techniques including allusions to Caribbean political activists and the centrality of the Mangrove itself as a community space. Over the course of the film, the political valence of the Mangrove moves from the background to the foreground, a shift that McQueen conveys through visual symbolism and dialogue, culminating in Darcus’s closing statement at the trial. In an interview about the film on the Big Picture podcast, McQueen emphasized the power of representing these stories in film because these histories are not often discussed, even within Black British communities. As a striking example, McQueen said on the podcast that one of his father’s best friends is Rhodan Gordon, but McQueen did not know Gordon was one of the members of the Mangrove Nine until he started working on the film. McQueen also described the post-traumatic stress that pervades the Caribbean community in England because of police brutality, which motivated him to bring Mangrove to life. This theme has even more contemporary resonance as the Small Axe films debuted amidst the worldwide Black Lives Matter protests that unfolded after a series of police killings in the U.S. Reflecting on the timing of the film, McQueen told the New York Times “it took a long time for people” in Britain “to believe the West Indian community about what was going on. All of a sudden we’re being believed. It’s taken a man to die in the most horrible way. It’s taken a pandemic. And it’s taken millions of people marching in the streets for the broader public to think ‘possibly there’s something about this racism thing’” (Clark, “In ‘Small Axe,’ Steve McQueen Explores Britain’s Caribbean Heritage). By depicting the complex stories of the Mangrove Nine, McQueen compels audiences to confront the experiences that Caribbean immigrants, and Black Britons more generally, have faced and continue to face.

I pledge that this is my own work in accordance with University regulations.

/s/ Julia Chaffers

Works Cited

Clark, Ashley. “In ‘Small Axe,’ Steve McQueen Explores Britain’s Caribbean Heritage.” The New York Times, November 11, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/11/arts/television/steve-mcqueen-small-axe.html.

McQueen, Steve, director. Mangrove. Amazon Studios, 2020.

“Rewatching ‘Tenet’ (at Home) in the Year of Christopher Nolan. Plus: Steve McQueen!” The Big Picture, December 17, 2020, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-big-picture/id1439252196?i=1000502767874.

That area where we roamed for the better part of an hour, Île Saint-Louis, is now my favorite part of the city. An island within a city, it presented a surmountable challenge for me to master; a smaller, contained area for me to tackle. When my sister visited me during my summer abroad the next year, we returned to the Ile Saint-Louis, and by that time I became the tour guide, leading us to our favorite bridge overlooking the Seine and the small shop with our favorite strawberry and mango sorbet. Here we are walking around the island, sorbet in hand.

That area where we roamed for the better part of an hour, Île Saint-Louis, is now my favorite part of the city. An island within a city, it presented a surmountable challenge for me to master; a smaller, contained area for me to tackle. When my sister visited me during my summer abroad the next year, we returned to the Ile Saint-Louis, and by that time I became the tour guide, leading us to our favorite bridge overlooking the Seine and the small shop with our favorite strawberry and mango sorbet. Here we are walking around the island, sorbet in hand.