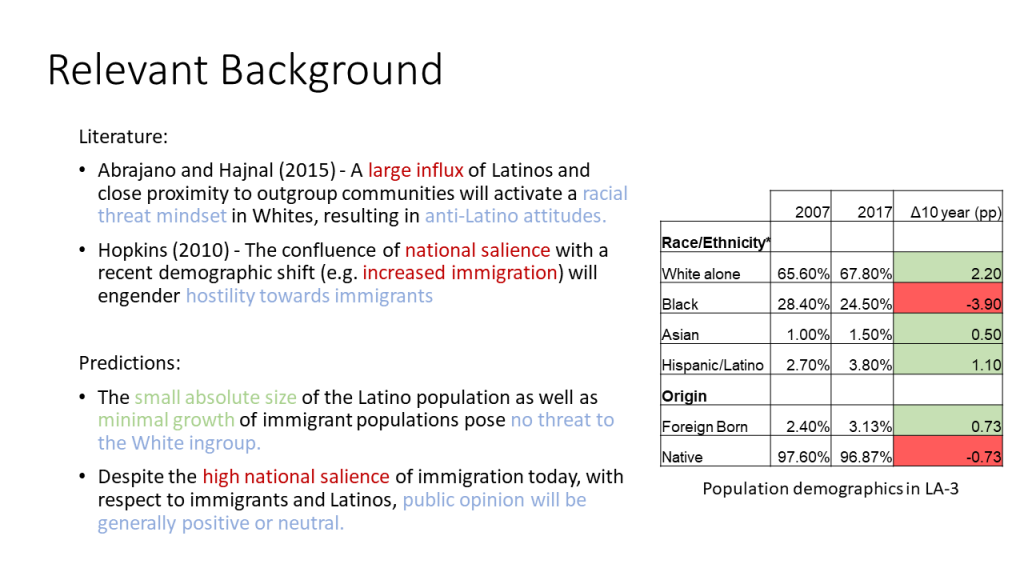

As was the case with Assignment 2, analysis of public opinion in LA-3 is made difficult by the fact that the foreign-born and Latino populations are miniscule (3.1% and 3.8%, respectively), and that the change in these populations is also insignificant (around 1% over 10 years). Thus, predictions made rely on examining the inverse of many of the claims made in relevant literature. The two sources used for prediction-making here are Abrajano and Hajnal (2015) and Hopkins (2010). Abrajano and Hajnal contribute two relevant findings here: firstly, that a large influx of Latinos is what triggers White ingroups (as compared to just a large Latino population), and secondly, that the mechanism through which anti-Latino attitudes develop is one of racial threat, where outgroup communities are viewed as a direct threat, such as through crime, competition for jobs, or burden on the social welfare system (2015). Based on the fact that there is a very small Latino population and very little growth, my first prediction was that the White ingroup would not feel threatened by the Latino population. The second relevant piece of literature is from Hopkins, who writes that hostility towards immigrants is again the result of two factors: national salience (e.g. from national crises like 9/11 or elite/media cues), and again a demographic shift with more immigrants (2010). There are many arguments to be made that salience is high today, and has been high since 9/11, and some evidence shows that salience has been particularly high since the beginning of the Trump presidential bid (Newman et al., 2018). However, once again the influx of Latinos/immigrants in LA-3 has been very minimal. Thus, despite high salience, I predict that Whites in LA-3 will hold generally neutral or positive views towards Latinos and immigrants.

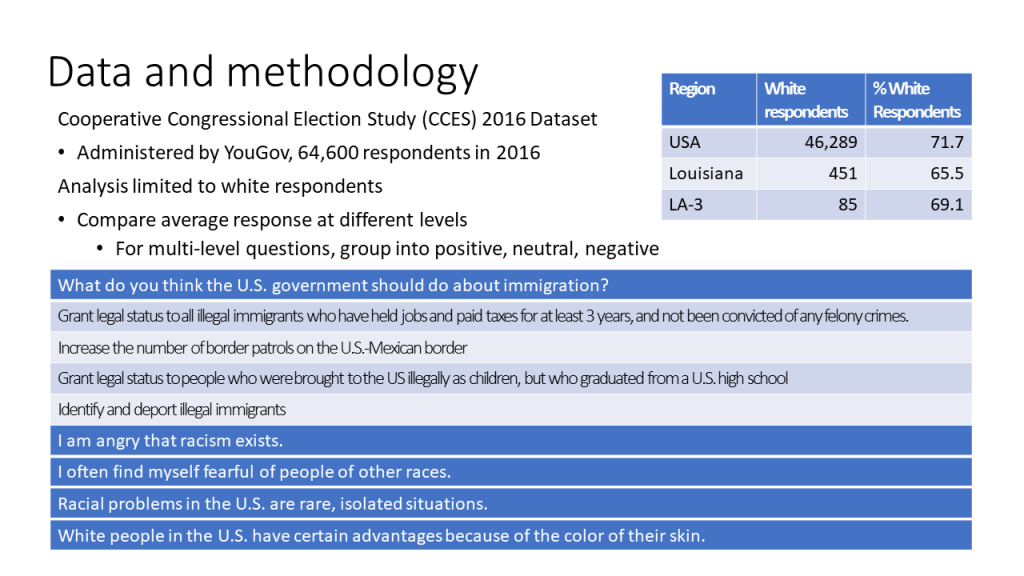

The data used in this study was taken from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) conducted in 2016. The study is conducted by YouGov, through a network of volunteers across the country, and reported responses from 64,600. The study was conducted in two waves: one set of questions is asked before the election, and one set after the election. The chosen for this analysis include 4 from before the election, and 4 from after, though the timing is not analyzed – only the question content is considered relevant here. For this analysis, only White respondents were analyzed, as the goal was to determine ingroup feelings about immigrants/Latinos. For context, responses to each question were tallied at the national, state, and congressional district level. The first set of responses stem from a single question, where respondents were asked: “What do you think the U.S. government should do about immigration?” Respondents were given several options and instructed to choose all the applicable options. Notably, not all respondents received the same options: a small, non-random subset received additional questions. This analysis only uses the common questions, so that hopefully the sample will be more representative. The four options examined are listed above, but essentially represent attitudes towards amnesty, border patrols, the DREAM Act, and deportation. The second set of questions, also listed above, measure attitudes towards race. Each of these questions had 5 levels of responses (strong agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, strong disagree). For purposes of analysis, these responses were grouped into agree, neutral, and disagree; some subtlety may have been lost by combining response categories but doing so made it easier to compare general trends across geographic units. The most directly applicable question of these 4 was “I often find myself fearful of people of other races”, which was used as a stand-in for a racial-threat mindset. However, it is notable that this question only asks about other races, and not Latinos specifically. Thus, any respondent who had feeling of fear about either Asian or Black people would also be grouped into this statistic. However, if anything, this should give an overestimate of racial threat response, whereas we are expecting a small overall response. The other three questions are not directly applicable to my predictions and are instead used to offer context for alternative explanations.

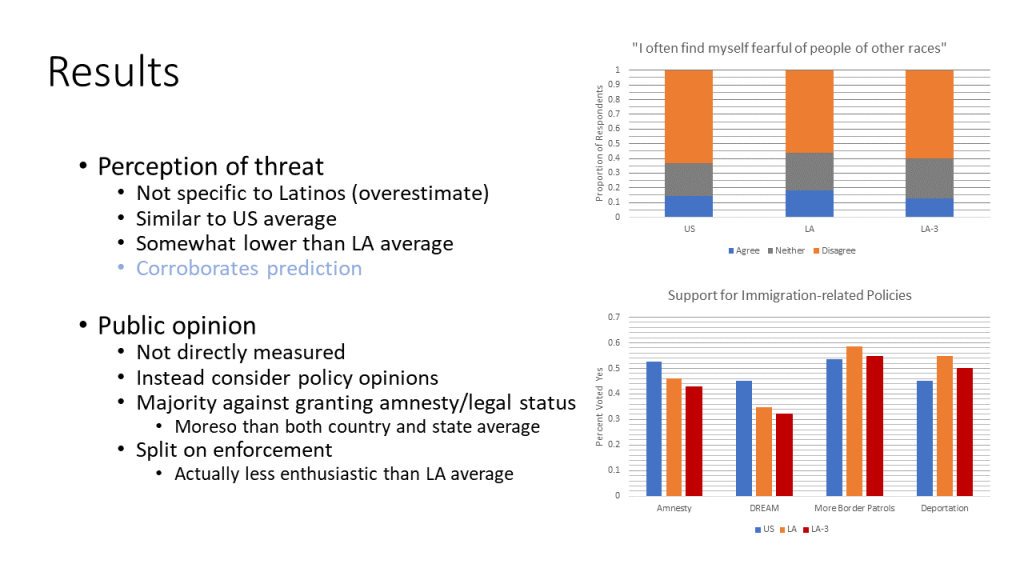

The first prediction, that natives in LA-3 did not feel threatened by Latinos, seemed to be corroborated. Or, to be more precise, they did not seem significantly more threatened than residents of Louisiana in general, nor the US at large. The second prediction was more difficult to evaluate. Firstly, there was not a direct measure of public opinion towards Latinos/immigrants in the CCES dataset. Instead, the aforementioned questions on domestic policy were used as an analog for general sentiment towards immigrants in particular. The findings here were split. On the one hand, Whites in LA-3 appeared to be less amenable towards the granting of legal status than either the national or state sample (10% fewer voted in favor of amnesty, and 13% fewer supported the DREAM Act). On the other hand, Whites in LA-3 were less in favor of stricter enforcement (e.g. more border patrols and deportation of undocumented immigrants) than the state average, though still slightly more than the national average. It is therefore difficult to draw conclusions about the general attitude towards immigrants, at least relative to the rest of the state. But in absolute terms, the data would seem to contradict the prediction: a majority of LA-3 residents oppose amnesty for immigrants and support greater enforcement against illegal immigrants, despite the fact that there are hardly any immigrants in their locale.

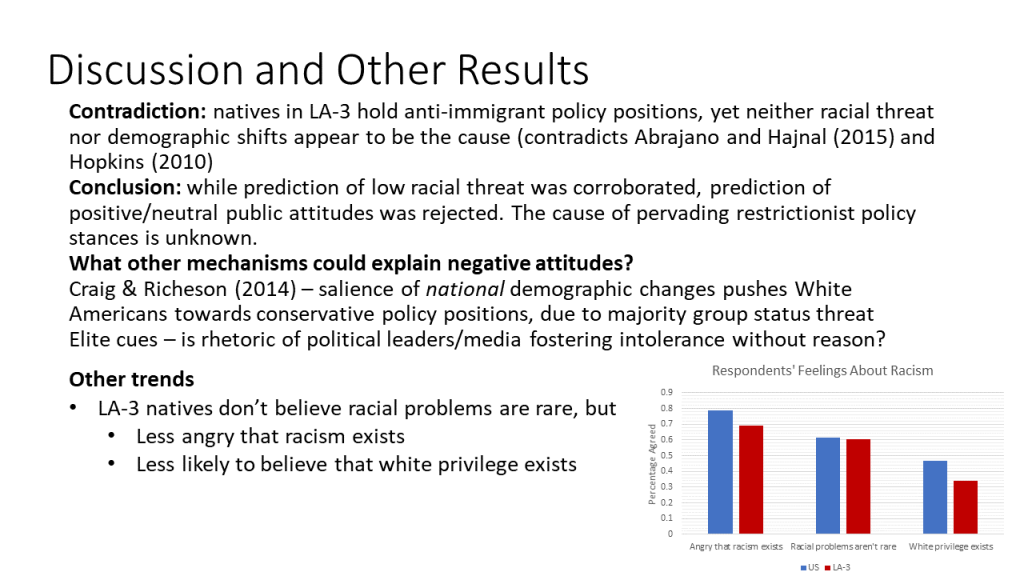

The results of this analysis are somewhat perplexing, as we observe negative attitudes towards immigrants, yet are left without a mechanism that would cause this, as both racial threat and demographic shifts were not relevant. This poses the question of what causes anti-immigrant attitudes in LA-3. There are a few possible mechanisms that could be responsible. Craig and Richeson found that the salience of national demographic change could be pushing White Americans towards more conservative policy positions, including restrictionist/anti-immigrant stances. The mechanism proposed is that Whites may feel that their status as the majority group is threatened by increasing populations of immigrants/Latinos/minorities, and thus embrace policies that are more favorable to the ingroup. Notably, this mechanism would not require any direct contact with immigrants, meaning that it could still apply in LA-3. In support of this theory, Whites in LA-3 recognize the existence of racial problems as much as Whites throughout the US, but they are on average less angry that racism exists, and less likely to believe that White privilege exists. This could suggest some degree of indifference towards disadvantaging minority populations, including Latinos and Latino immigrants. An alternative theory would be priming via elite cues. A large body of research demonstrates that political leaders and the media can influence attitudes towards immigrants (Abrajano and Singh, 2009; Jones and Martin, 2017; Dunaway et al., 2010). While studies generally focus on the intersection of various factors (demographic shifts, distance from border, etc.) with elite cues, it is generally understood that to some degree people take on the views of their political representatives. In Assignment 1 I found that the Congressman of LA-3, Clay Higgins, was extremely vocal and consistent about his restrictionist stance. In such conditions, where the media and political elites may tout anti-immigrant policies, and there are few local immigrants to contradict this perception, it is not unreasonable to believe that Whites in LA-3 developed a negative affect towards immigrants using the only information they had available. While this claim is unsupported by empirical data, it is a promising avenue for future research.