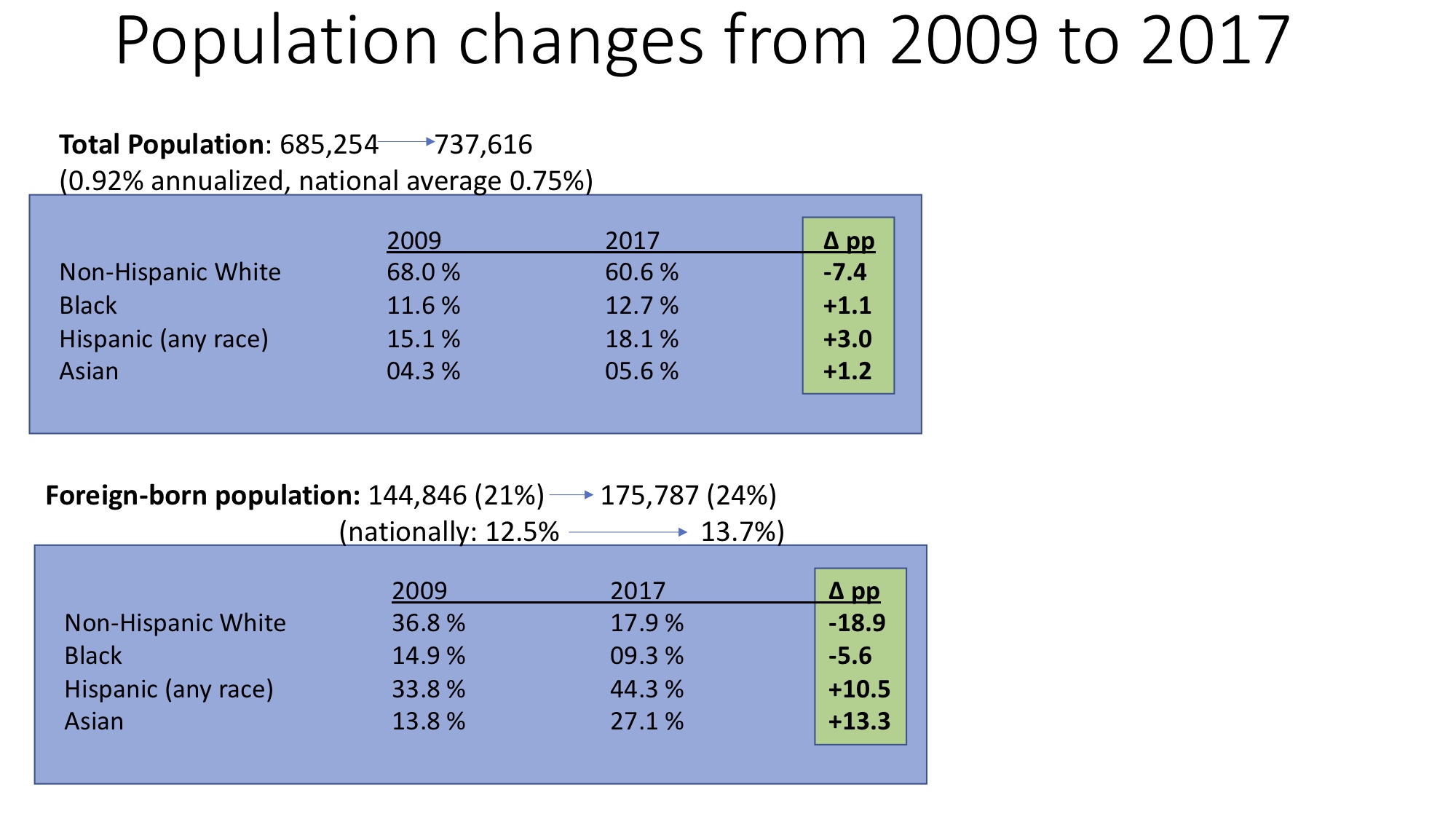

I. Population Changes since 2009

The first slide reports changes in each race’s representation in CT-4 from 2009 to 2017. We see that CT-4’s total population grew faster than the national average at an annualized rate of 0.92%. The share of residents born abroad is both higher and grew faster in that period than the national rate, as well.

The top-line numbers in the green box give the overall percentage point changes of each race both in total and among the foreign-born population in CT-4. Among the total population , we see marginal increases in representation across all races, with whites making up a smaller share. This difference is even more pronounced among the foreign-born population; Asians and Latinos are clearly driving immigration into the district.

II. Literature review

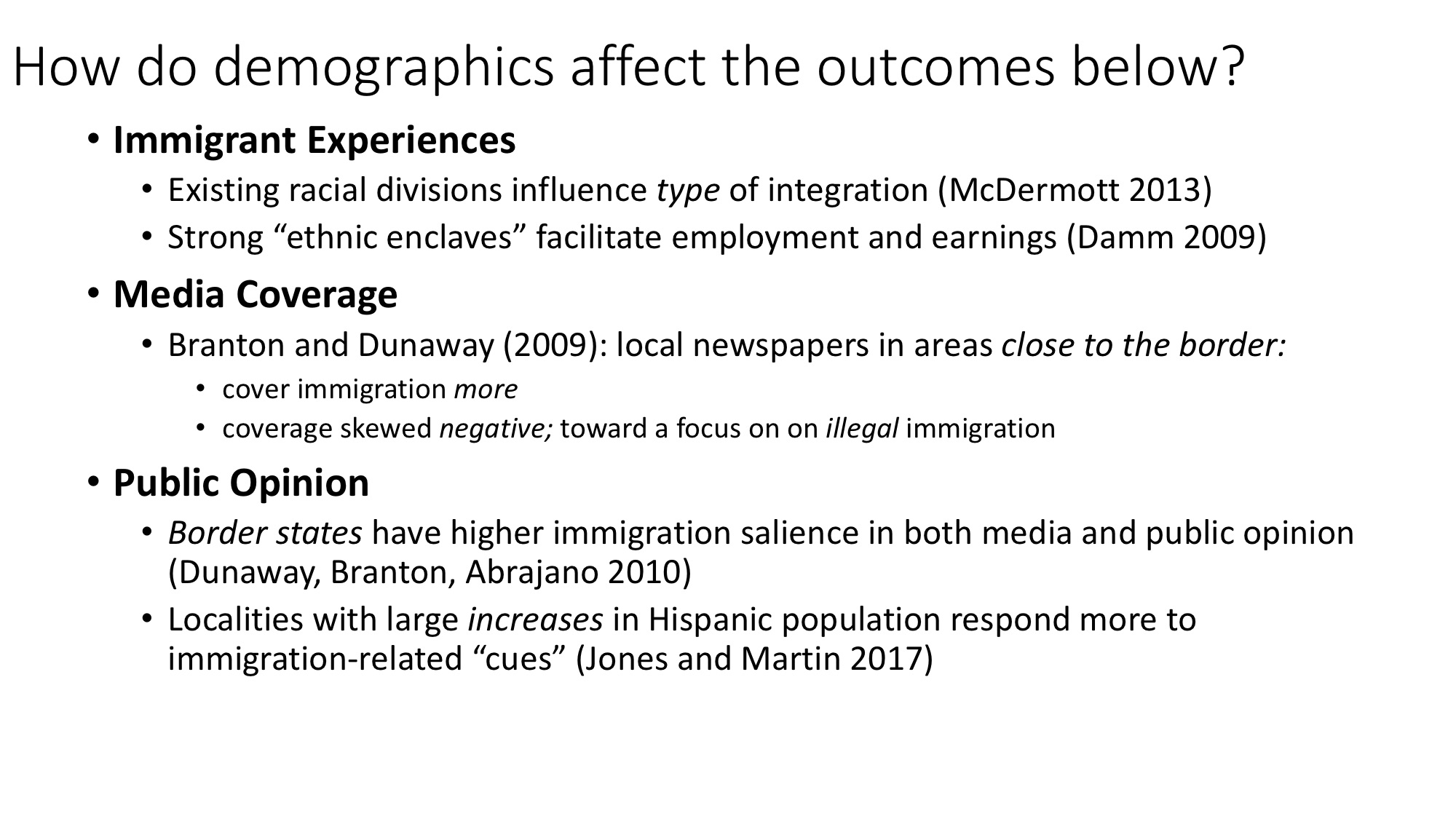

We know that both local and national characteristics drive immigrants’ integration experiences and public image. I consider the dependent variables in turn.

Immigrant experiences: Monica McDermott coins the term “bureaucratic integration” to describe one means by which immigrants get involved with their communities. She argues that immigrants choose to get involved in organizations like schools or local policing when there is not racial animosity between them and local whites; this is more likely when local black Americans are the existing outgroup. With respect to economic integration, we can expect a causal effect of the strength of ethnic communities on labor market outcomes. Specifically, Anna Damm finds evidence in Denmark that linguistic similarities allow a higher flow of information for immigrants in “ethnic enclaves.”

Media coverage: Literature has focused on tone and prevalence of immigration coverage in the media. Branton and Dunaway (2010) find that local media in border states “generate a higher volume of articles about Latino immigration, articles featuring negative aspects of immigration, and articles regarding illegal immigration.”

Public opinion: While we have seen in class that the salience of immigration can often depend on national-level features like big news stories, local-level characteristics matter too. Immigration is a more salient issue for citizens of border areas according to Dunaway et al. (2010). Also, big demographic changes can make immigration more important to voters; Jones and Martin (2017) identify defining features of areas with a big change in the Hispanic population. At the state level, states in the 75th percentile or above in change from 1990-2010 (~375%) count, and they use a continuous measure of district-level change. They find strong relationships between “large change in Hispanic population” and “influence of candidate cues on immigration,” meaning that in such areas, Republican politicians’ restrictionist cues generate more of a response than in other areas.

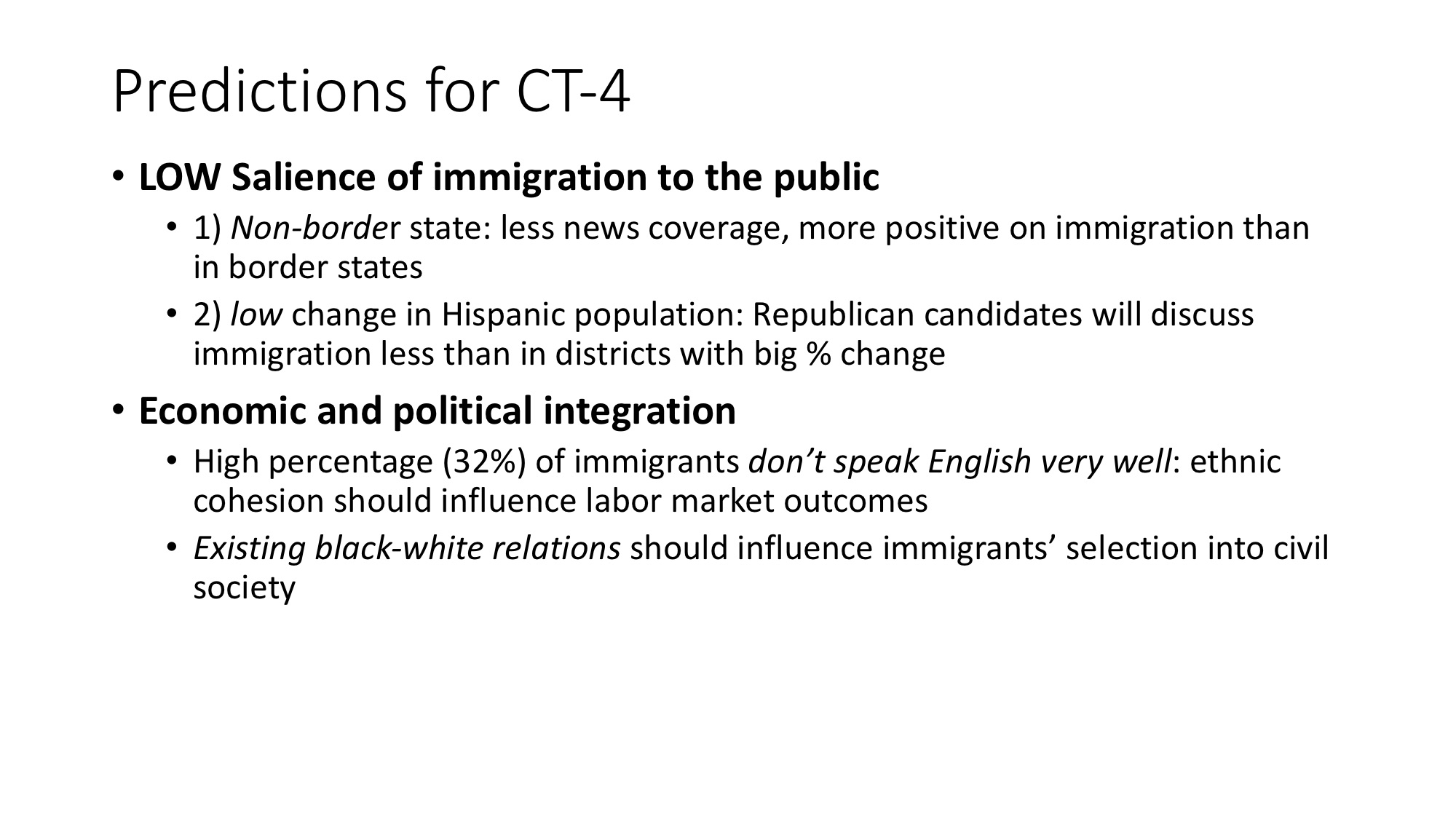

III. Predictions for CT-4

With respect to immigrant experiences, we need to interview citizens and immigrants in the area to understand the salience of race in both their decisions on how to integrate into civil society, as well as the extent to which they rely on ethnic networks to get economic information. The 2017 ACS estimates that 32% of the foreign born population speaks English less than “very well” (compared to 3.7% of the native population), suggesting that ethnic cohesion may be a relevant variable.

With respect to immigration salience, we would expect Republicans not to emphasize immigration/restrictionism because Connecticut is not a border state. While CT-4 has experienced a 3 percentage-point increase in Latino population, which is much larger than the 1.2 pp increase in the US, it does not seem to get close to the 375% increase determined by Jones and Martin (2017). Furthermore, we should expect less local media coverage, and more positive coverage, of immigration than in similar border states. We next turn to measuring this effect.

IV. Testing the effect of location

IV. Testing the effect of location

I will ask the question whether Connecticut’s status as a non-border state causes its local- and state-level media coverage of immigration to be systematically less prevalent and more positive. I will employ a matching design, whereby I identify districts that are similar to CT-4 in every conceivable way that could influence media coverage of immigration, with the only difference being that the district is in a border state. That is, I will identify border-state districts similar to CT-4 in income, (change in) racial makeup, percent foreign-born, and partisanship. On the (very strong) assumption that we have observed ALL covariates that could conceivably influence media coverage, we can estimate the causal effect of border status on media coverage. After identifying these districts, I will acquire newspaper articles using the LexisNexis database, coding articles for their topic and their sentiment. I can then test the rate of immigration-related articles as well as their positivity/negativity, to test the border-state hypothesis of Branton and Dunaway (2009).