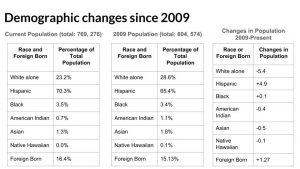

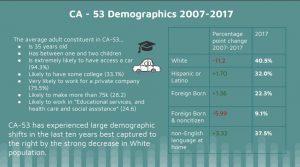

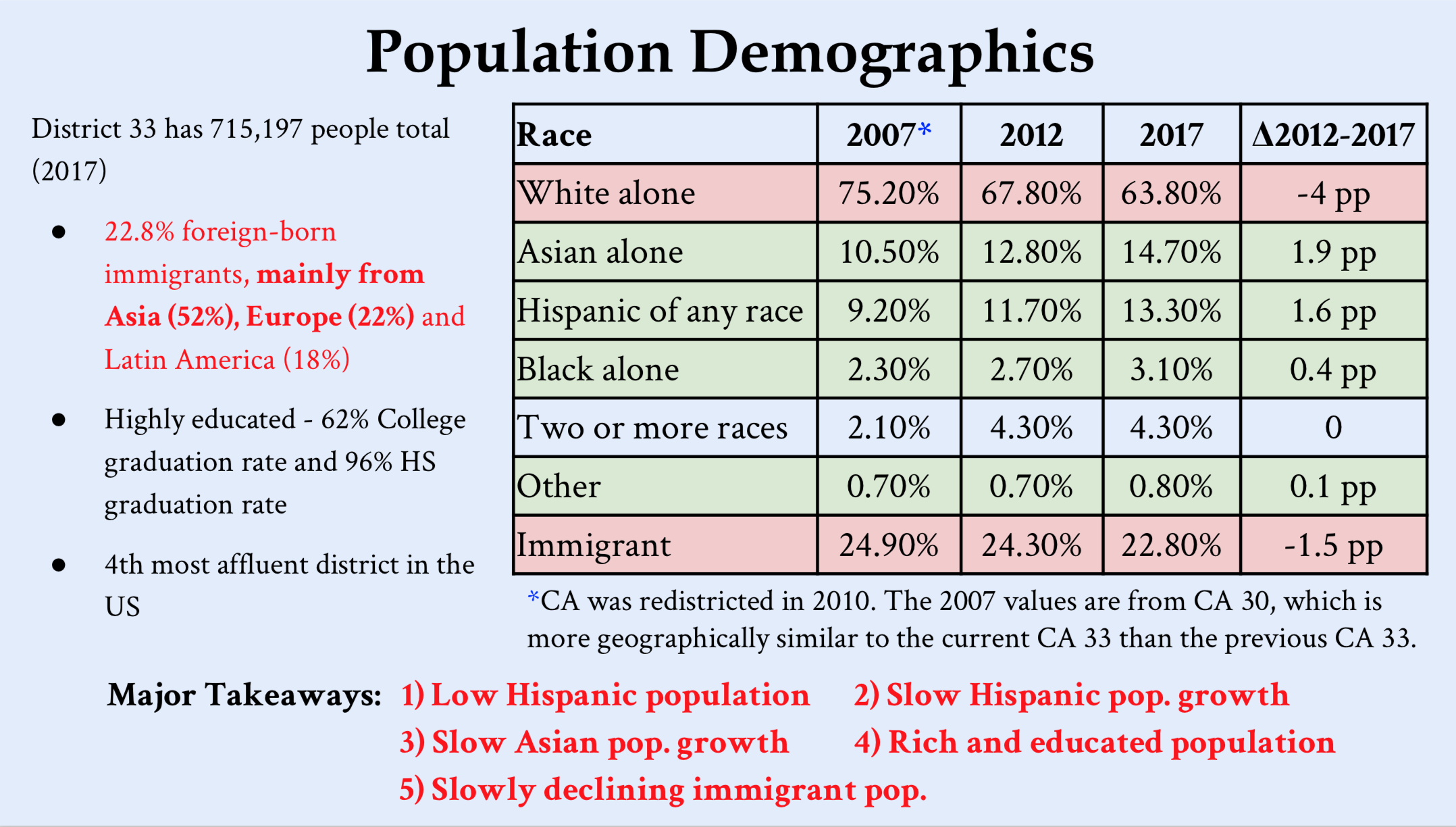

Slide 1: Population Demographics

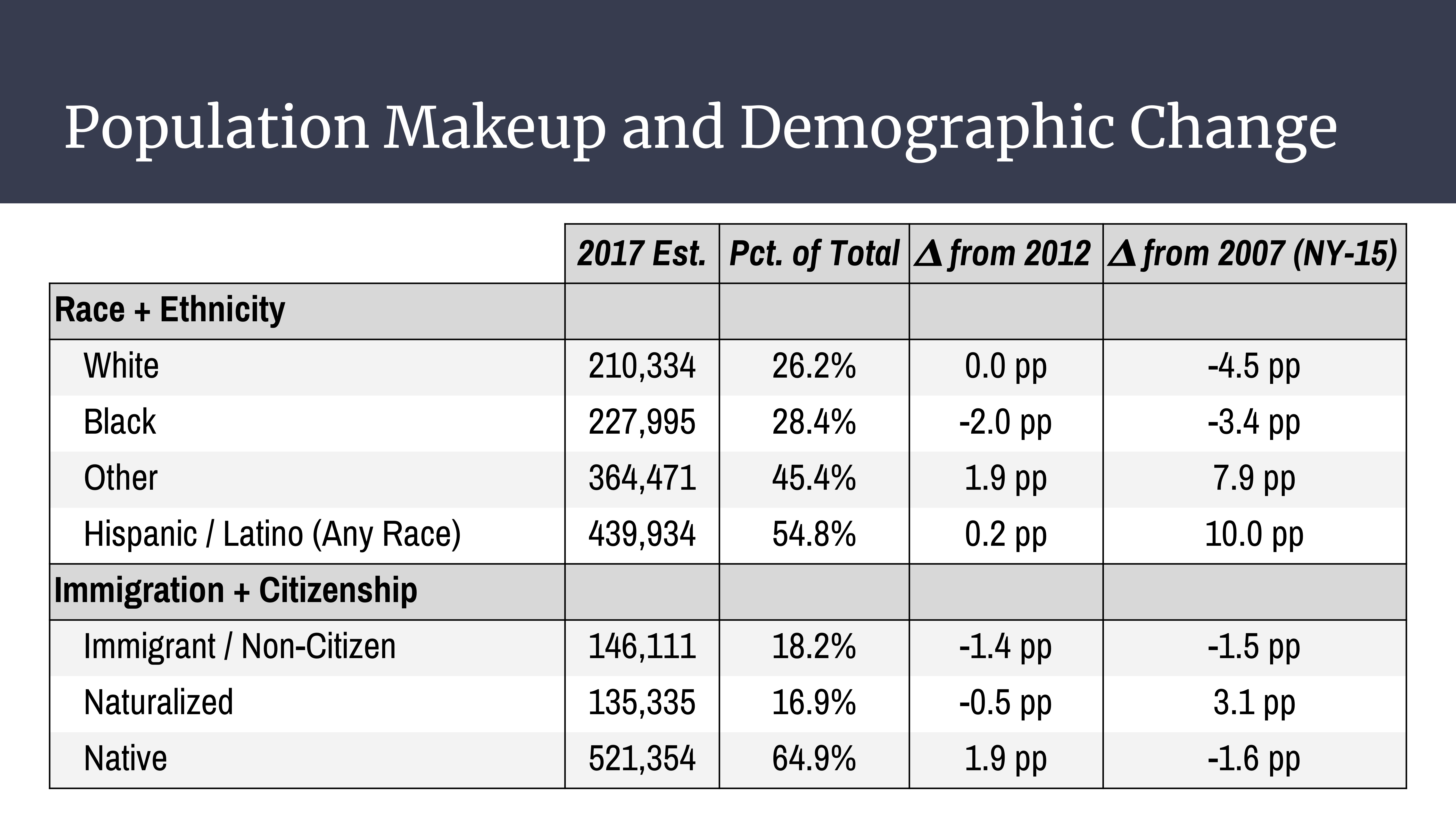

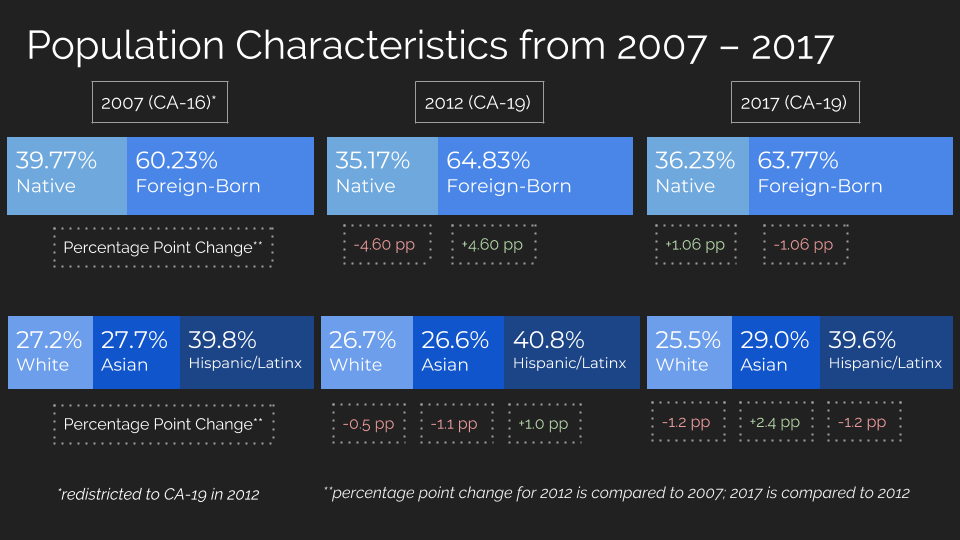

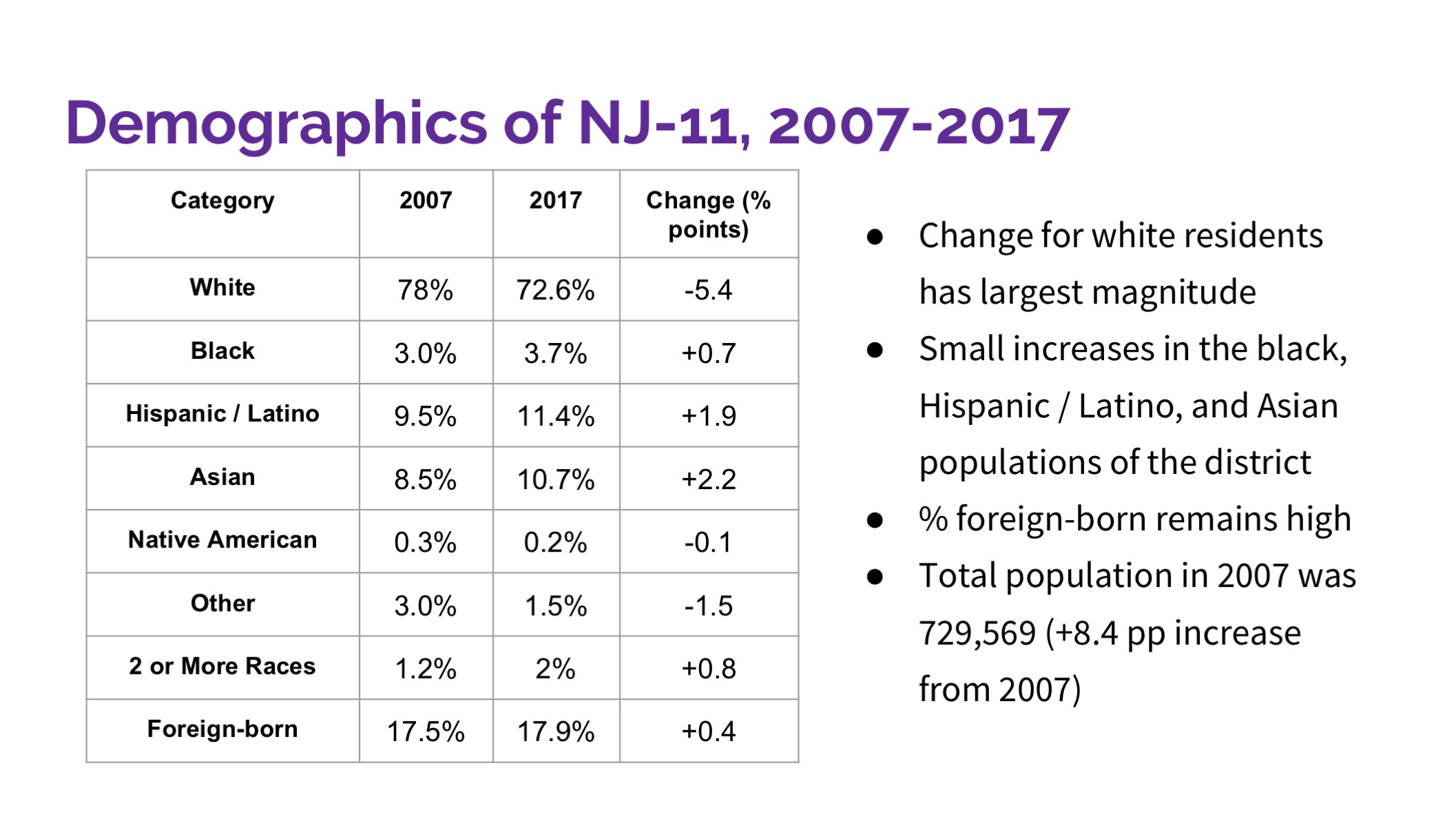

This slide provides an overview of the unique demographics of New York’s Thirteenth Congressional District and the changes that have taken place over the past decade. We use 2017 estimates as the most recently available ACS data; to demonstrate demographic change we show percentage point differences from 2012 and 2007. It is important to note, however, that the 2007 comparison is drawn from the then-Fifteenth District. Before redistricting, over 80 percent of the current area of the 13th district was part of the 15th, however we recognize that these comparisons are not exact and that some margin of error must be taken into account.

Despite this, there are several inferences we can make. The first is that over the past decade, both white and black elements of the population have been replaced by new racial groups, including Asians, those of mixed race, and those not identifying with any of the above. At the same time, the district, already one of the most Hispanic in the nation, has become steadily more so. These effects, however, have either slowed in the last five years or are attributable to the 2011 redistricting. More confidently, we can observe a slow replacement of the native population with those of foreign origin, and a foreign population that is politically integrated, as evidenced by the fact that the foreign-born naturalized percentage is growing at nearly the same rate that the native population is shrinking. Taken together, these facts show a district undergoing demographic change, though some effects are stronger than other. We will analyze the implications of these demographics in the following slides.

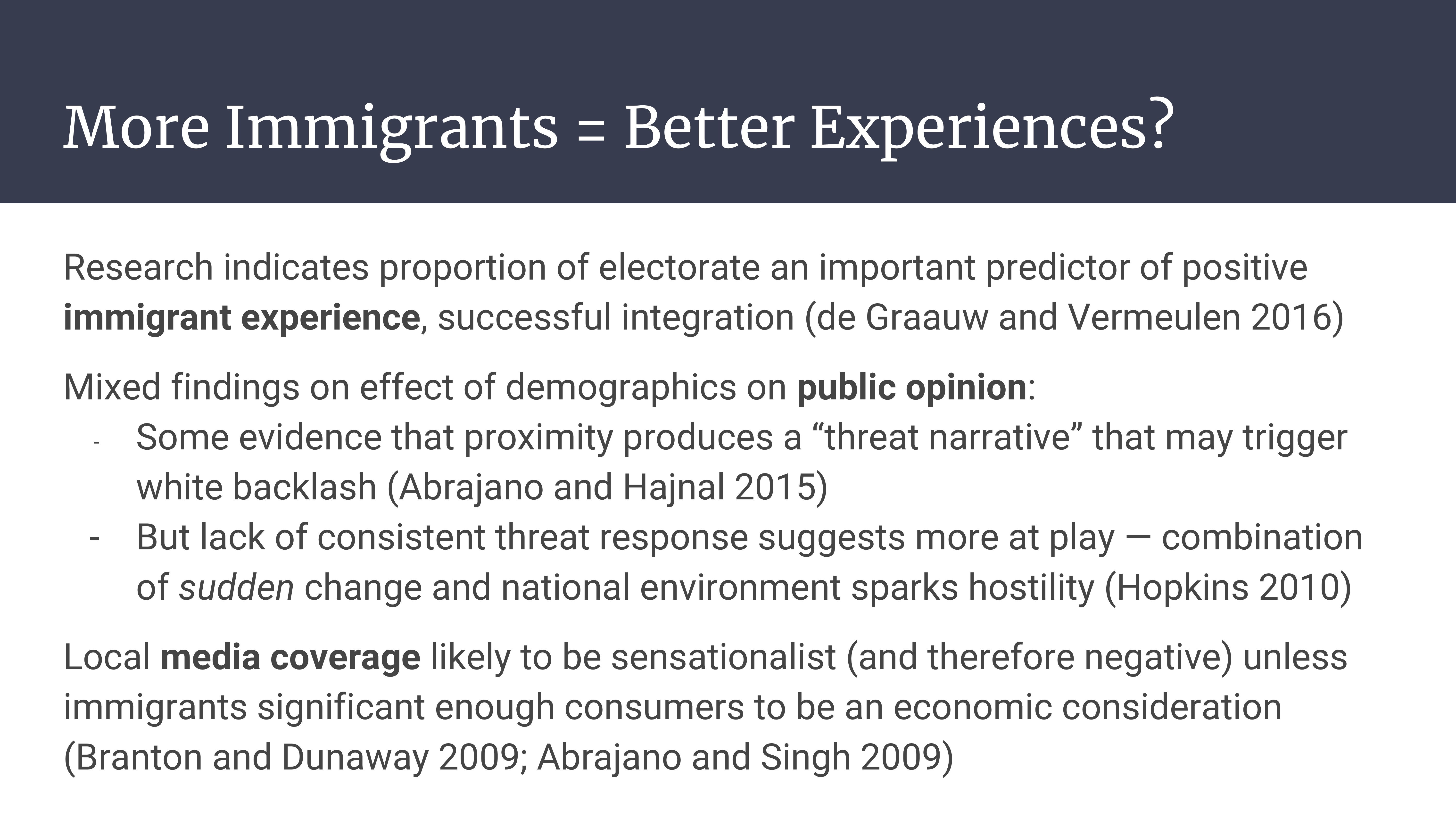

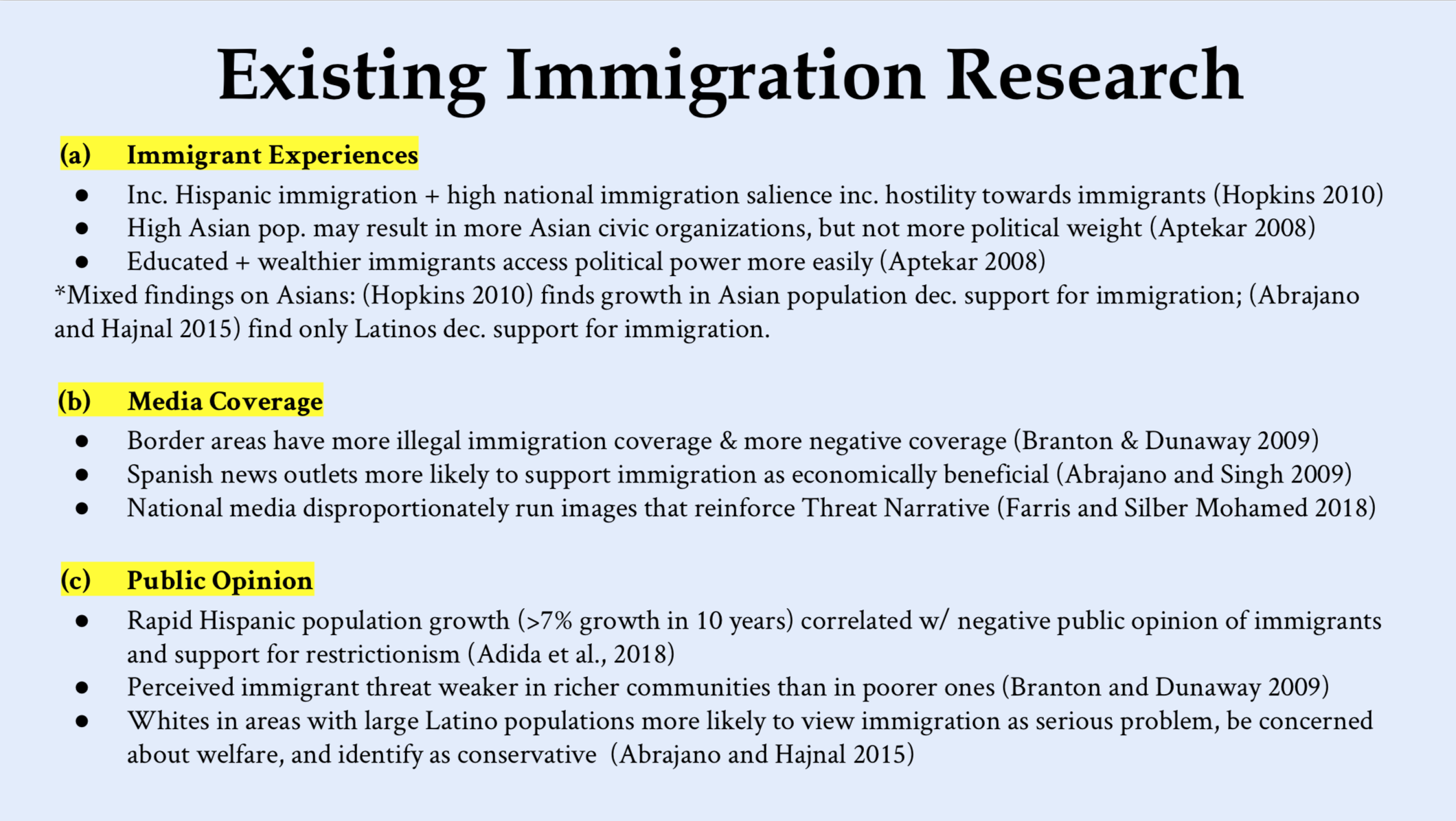

Slide 2: Selected Scholarship

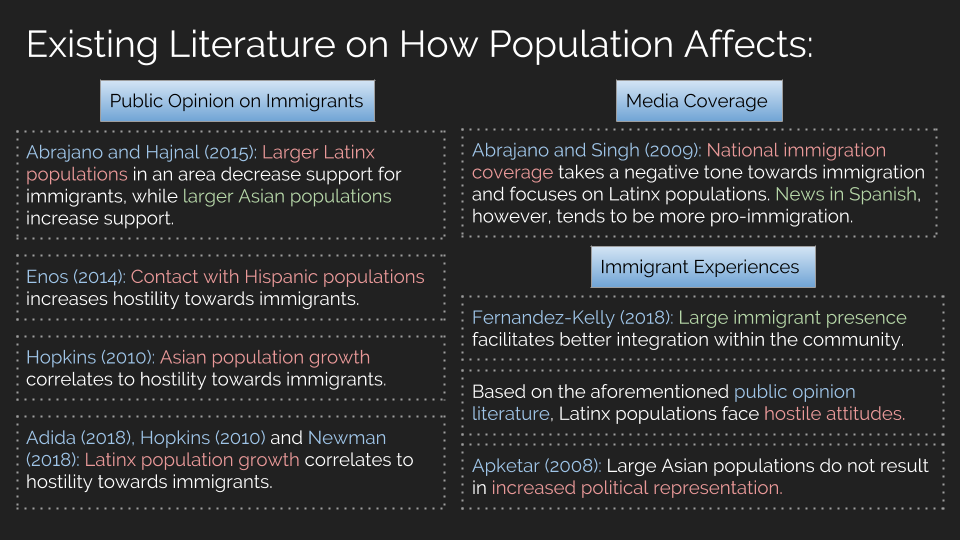

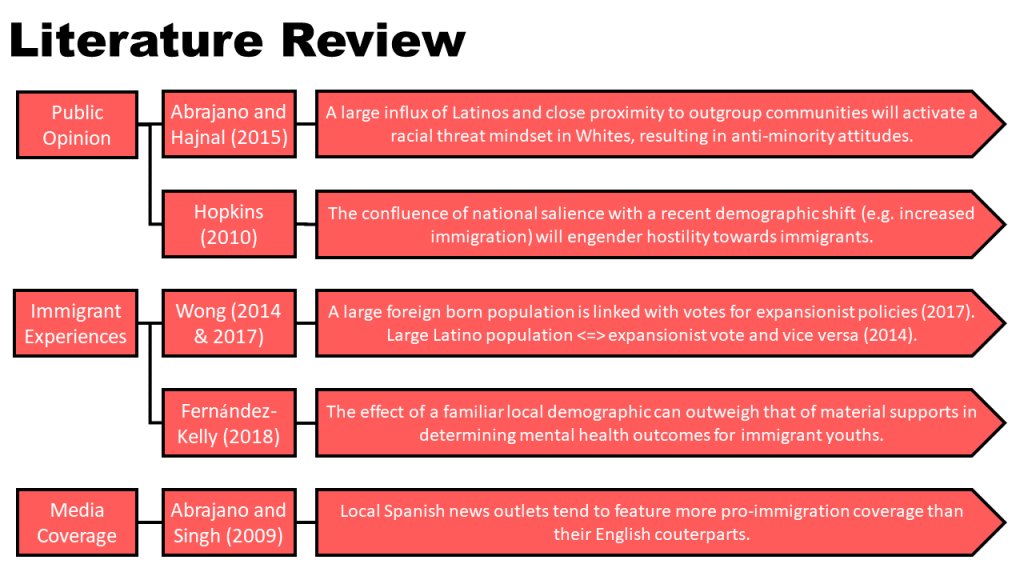

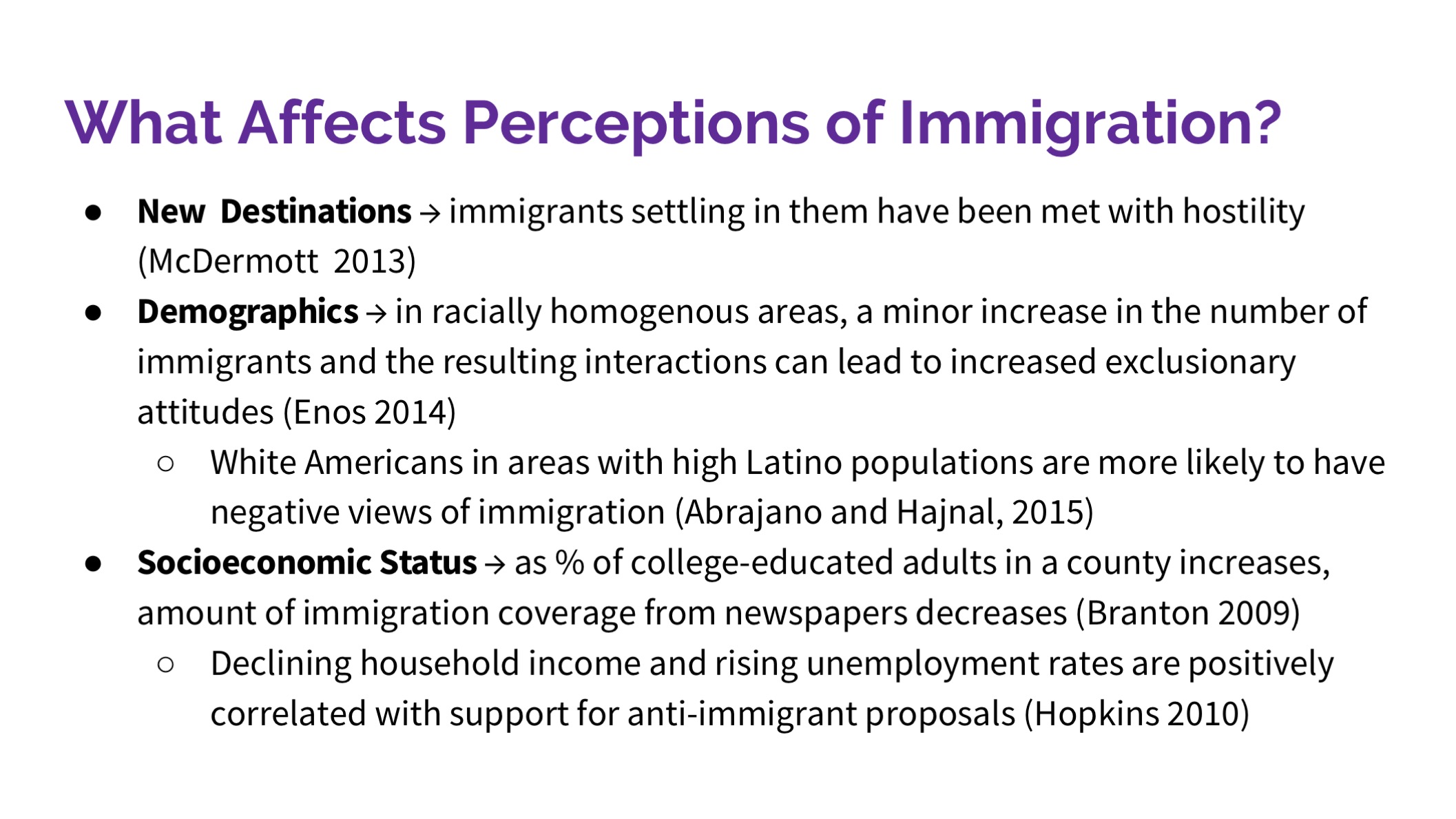

The effects of immigrant populations on various societal outcomes has been hotly debated in past scholarship. Research by de Graauw and Vermeulen (2016) has demonstrated that the proportion of immigrants among the electorate and their relative population levels are significant predictors of their social and political integration at the local level. Along the same lines, we can predict from research by Branton and Dunaway (2009) as well as Abrajano and Singh (2009) that media coverage will become more favorable to immigrants as their levels rise, as it increasingly considers their interests due to their rising consumer power.

In the battleground of public opinion, there are those who argue that increased levels of immigrants will provoke a sense of “racial threat” and aggravate negative feelings toward immigrants and immigration (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015). On the other hand, many have observed opposite or no effects, leading some to conclude that there is more at play. According to one such theory, Hopkins (2010) argues that it is only the interaction of sudden change with national immigration salience that sparks backlash. The relevance of these theories to our district will be addressed in the next slide.

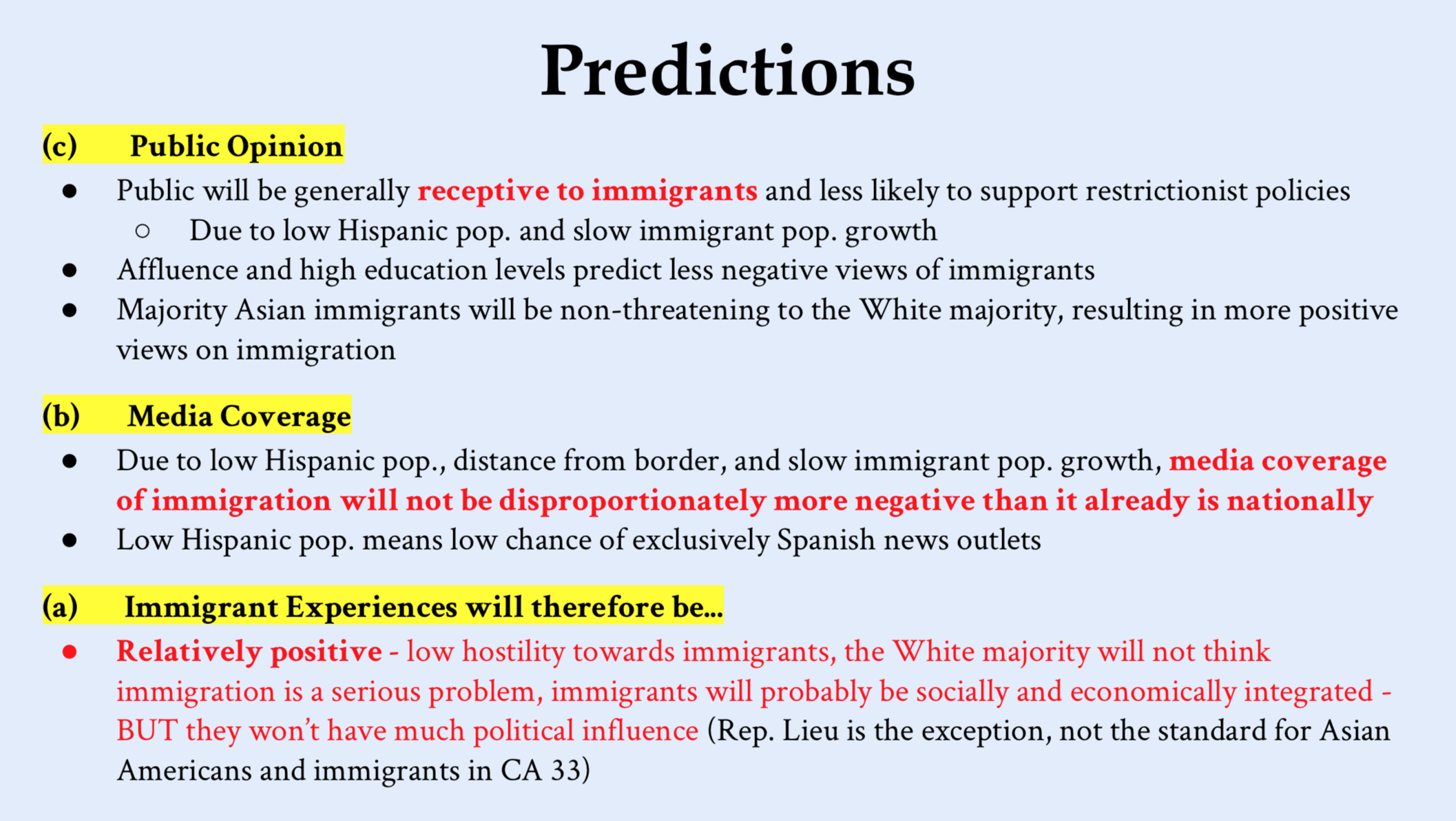

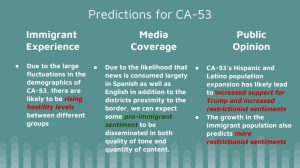

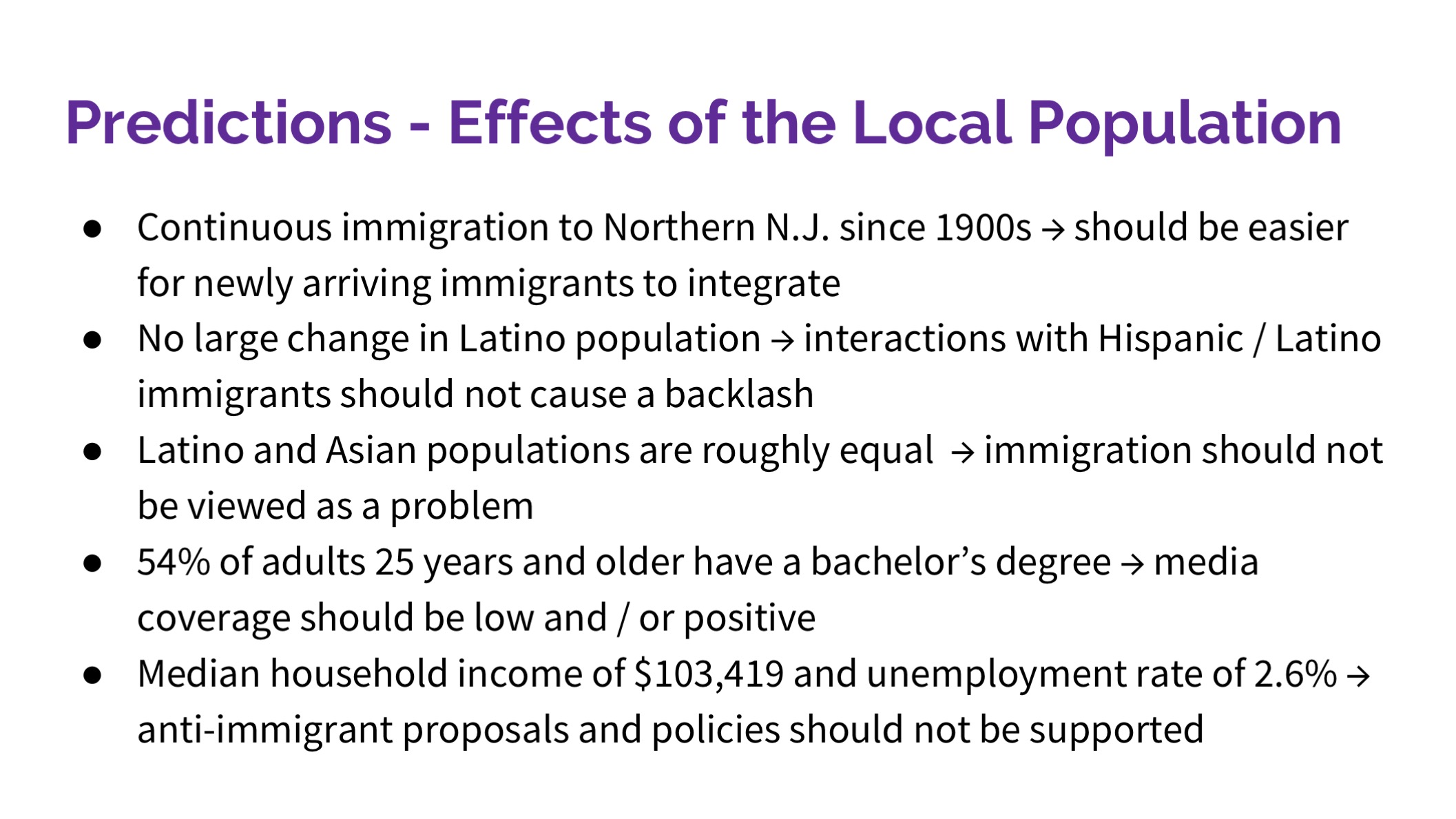

Slide 3: Predicted Effects

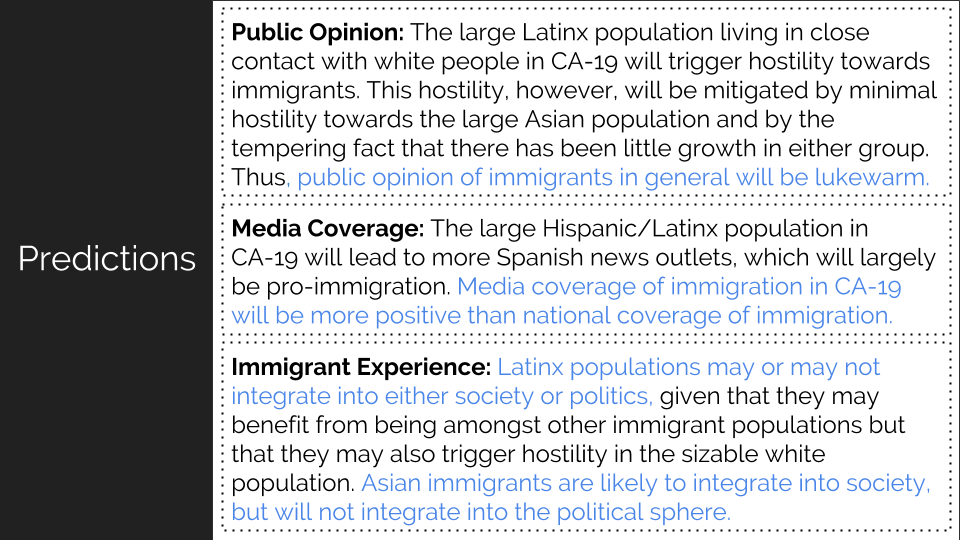

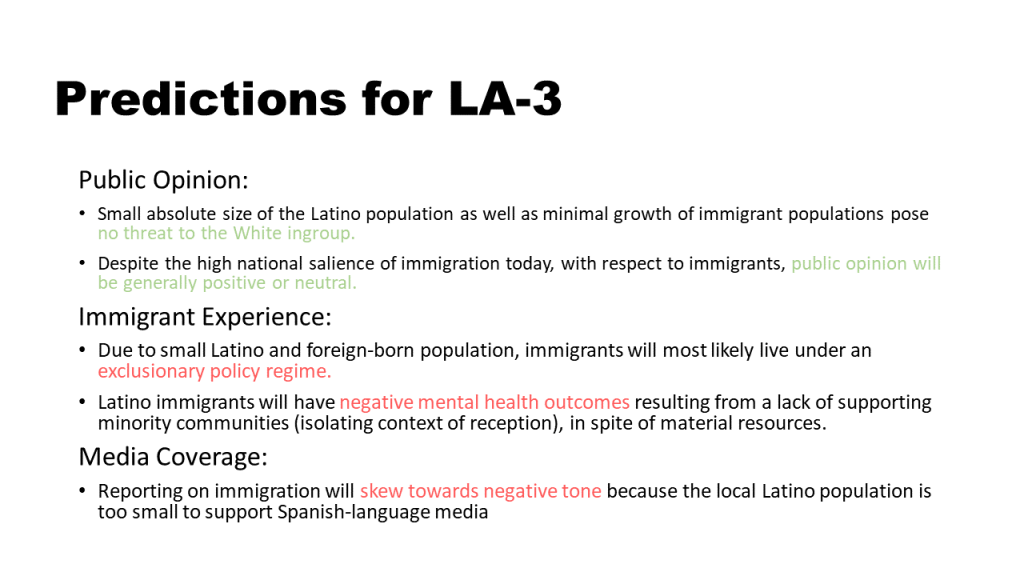

Given the demographic makeup of our district, we suggest three predictions about the effects of recent developments. We expect that the population changes caused by the immigrant growth rate, while perhaps of relevance to local leaders, are not sudden or significant enough to meet the threshold described by Hopkins and others to trigger local opposition or backlash. Second, we predict that immigrants will continue to integrate themselves into society, following the example of the large numbers presently doing so in the local context. Third, although already significant enough within the district to merit favorable media coverage, we expect that as the immigrant demographic continues to grow, the media will continue to see them as an important economic constituency, thus supporting further coverage of their interests.

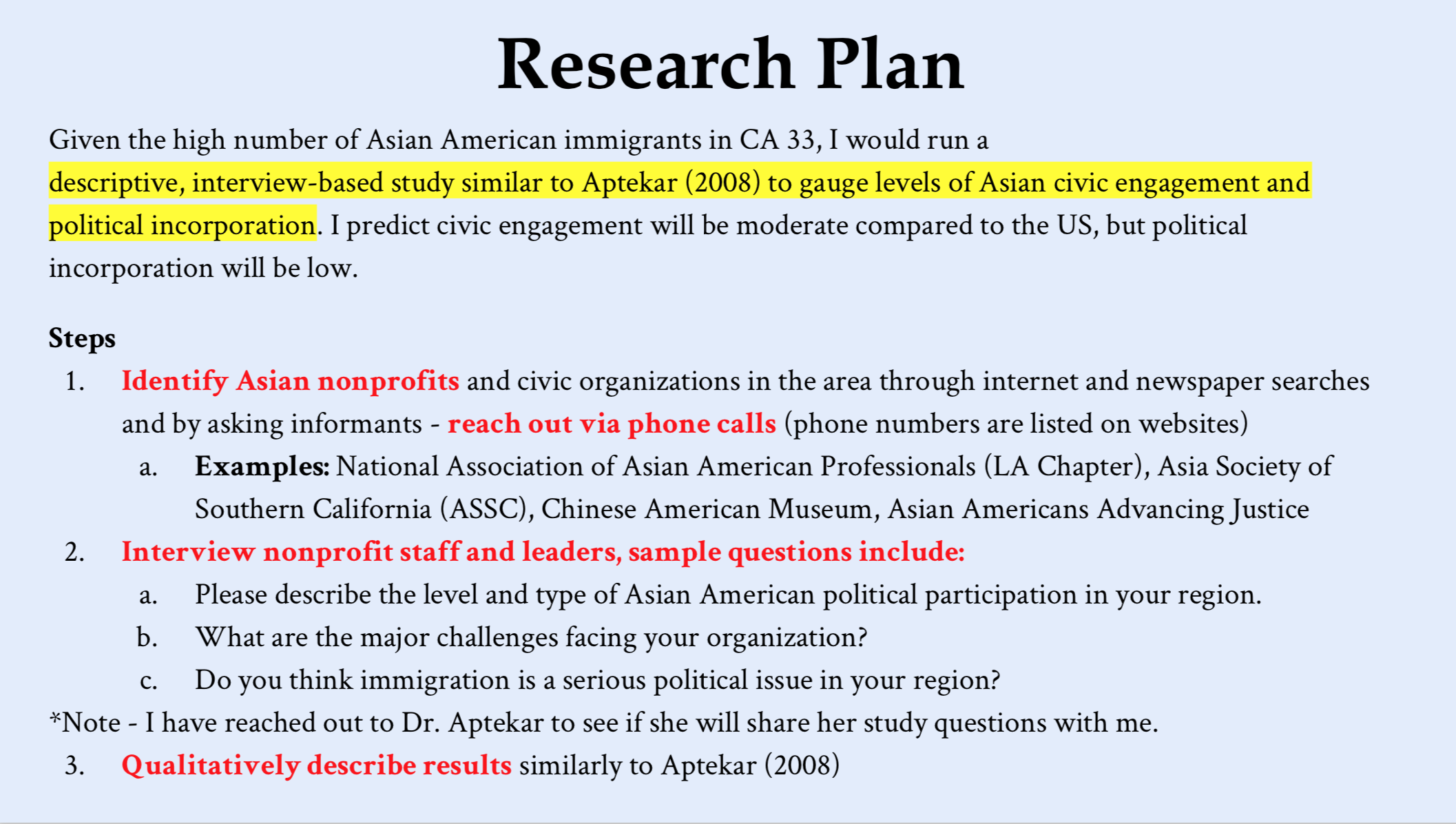

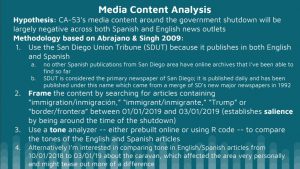

Slide 4: Research Proposal

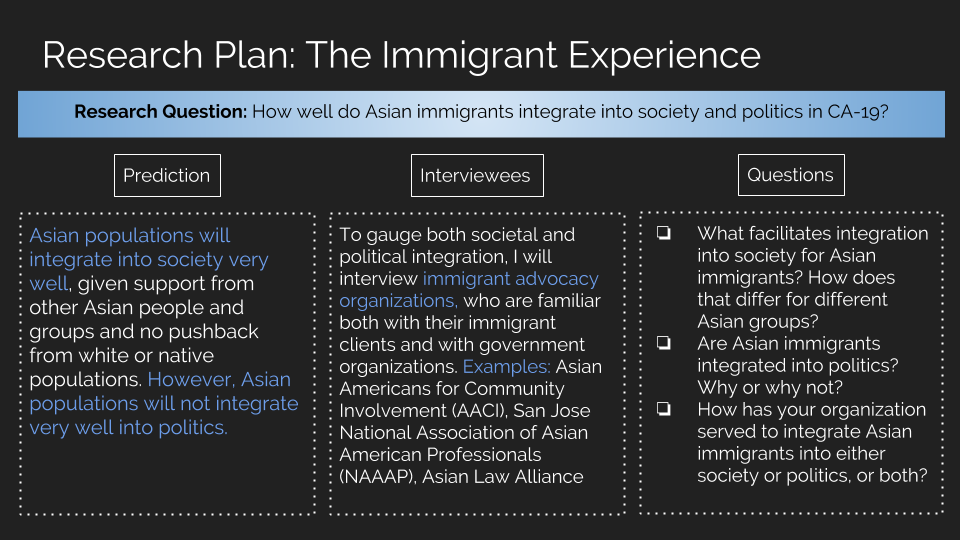

To further the research the effects of district population demographics and their changes, we propose a research project consisting of qualitative interviews with local political figures and non-profit immigrant advocacy organizations. We aim to examine if changing demographics have led to backlash toward immigrants, placing the results of our research in conversation with theories of racial threat as well as the contact hypothesis. To this end, we will ask questions seeking evidence of ethnic tension and racial resentment within the district. This will hopefully allow us to determine the impact of demographic change and the accuracy of our prediction that the local experience will be better for immigrants today than ten years ago.

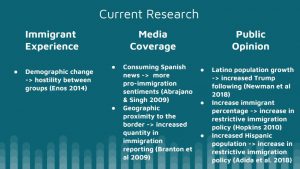

Slide 2: Existing Immigration Research

Slide 2: Existing Immigration Research