The representative I am studying, Congressman Dan Crenshaw, recently advocated for quicker denials of asylum seekers and an expansion of detention facilities to stop Central American migrants from coming. I use Professor Massey’s article “What were the paradoxical consequences of militarizing the border with Mexico?” to argue that pursuing these tough actions on asylum seekers will only incentivize them to use illegal methods to get into the country and to stay in the country once they do get across illegally. I then tie the growth of undocumented immigrants that Massey shows to Abrajano and Majnal’s argument that a growing Latino population causes more cultural anxiety and fears that Latinos are depleting social services, which has caused today’s hostile environment around immigration. I argue that the solution to this problem is to give temporary work visas to males from Central America, like what Massey notes was done pre-1960s, so they can easily come back and forth to Mexico, where I argue their families should stay as Mexico has been welcoming to migrants and shares the same language and similar culture to the Central Americans. This solution gives migrants economic opportunities while minimizing backlash towards changing demographics and potential social service competition. Finally, I use Professor Tom Wong’s theory of a large foreign-born population pressuring politicians to support less restrictive policies to argue that the large foreign-born population in Congressman Crenshaw’s district could organize and threaten Crenshaw’s seat if he continues supporting tough immigration measures.

“Congressman Crenshaw, “tough” asylum policies would fail and incentivize more illegal immigration

Congressman Dan Crenshaw (R-Texas) took to the national airwaves this week advocating for larger detention facilities to house surging numbers of Central American migrants escaping violence and poverty and closing loopholes that give preferential treatment to migrants with children. The problem Crenshaw identifies is real: many migrants are turning up with their children at the southern border and voluntarily turning themselves in to authorities, knowing that bringing children increases their chances of being released into the country under American asylum laws. But his tough solutions ignore why people come to the United States, may cause the undocumented population to rise further, and hurt him politically with immigrant constituencies.

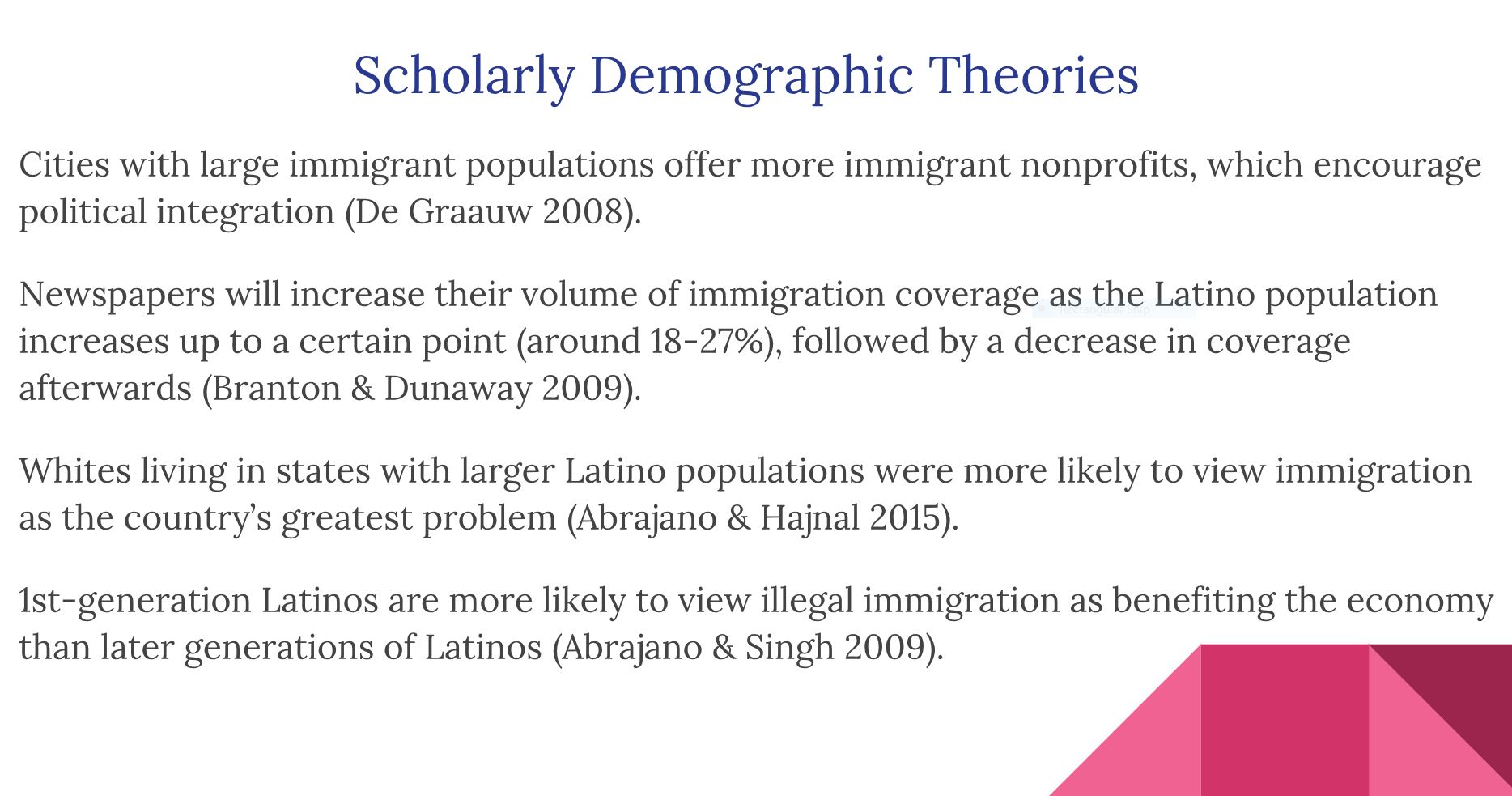

To understand why Crenshaw’s solutions will make the migrant problem worse, an outline must be given on the history of Latino migration in the United States. In a forthcoming article by Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey titled “What were the paradoxical consequences of militarizing the border with Mexico,” Massey notes that Latino migrant workers have come to the United States for jobs since the 1940s, with the trend always being that migrants would work temporarily in the US and make many trips back home (mainly to Mexico) to spend time with their families. This circular migration continued even after the Bracero program, which gave migrant farm workers temporary visas, ended in the 1960s. Even though the migrants were newly “illegal,” their stay in the United States remained temporary and their families remained abroad. This changed in the 1980s with expanded fencing and detention centers along the border, which made traditional circular migration more burdensome and costly. Therefore, migrants chose to settle in the United States, instead of returning home, and paid for their families to be smuggled into the United States. The undocumented population skyrocketed, putting Americans into more contact with people who did not speak their language and were relatively much poorer than themselves.

UCSD professors Marisa Abrajano and Zoltan Hajnal identify that this explosion of poor Latino migrants coming to the US illegally helped cause white working-class voters to believe they were in greater competition for social services with Latinos, as well as facing changing cultural norms like bilingual education. While these claims are often disputed (undocumented immigrants are ineligible for most welfare benefits), this group of voters has made their disdain clear in their support for restrictive immigration policies, like the wall and limiting the volume of immigration.

The failure of past “tough” immigration policies boosted the undocumented population to its current levels and created today’s hostile political climate around immigration. Therefore, if we were to implement Congressman Crenshaw’s ideas and prolong detentions of Central American families, we would incentivize them to pursue other (illegal) ways of getting into the country, which will be both more dangerous for the migrants and lead to more backlash from native-born Americans.

Pursuing tough immigration policies will never fully negate the enormous economic benefits migrants obtain from immigration. What we should instead aim to pursue is a plan like what we did in the past: give work visas to young men that allow them to easily move between the United States and Mexico. Their wives and children should stay in Mexico, a country that has been very welcoming to the migrants and shares the same language and similar culture to the migrants. Mexico has expanded the issuance of humanitarian visas to migrants over the past year and cut down on deportations, making it a safe place for women and children to stay. Moreover, the children staying in Mexico means they will not be eligible for American public education, an expensive program paid for by American taxpayers and the subject of past controversy, such as California’s Proposition 187 in 1994, which sought to ban undocumented children from attending public schools.

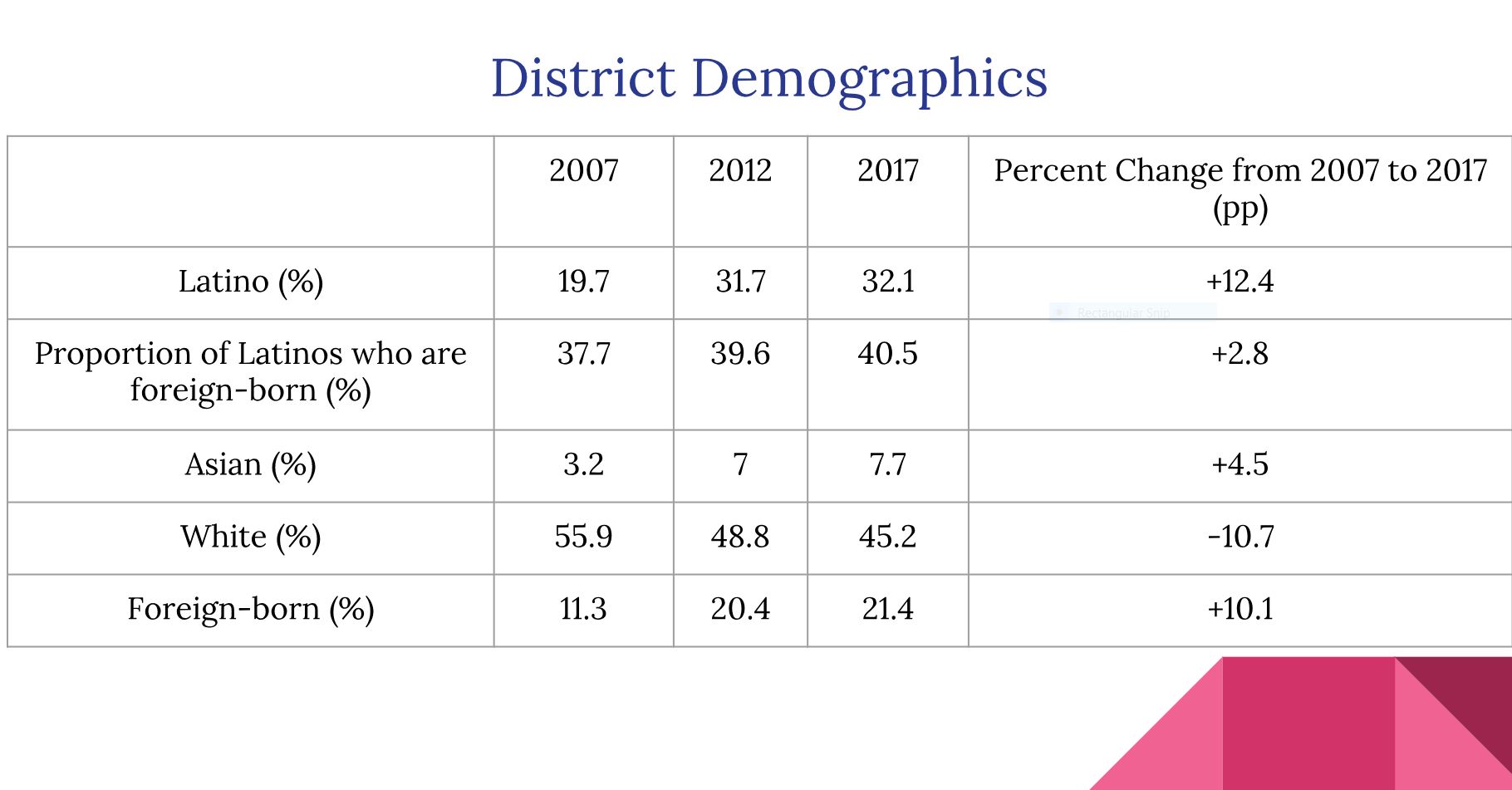

A last point involves electoral consequences for politicians, like Crenshaw, that continue to be tough on immigration. UCSD Professor and former advisor to the Obama administration Tom Wong notes that a large foreign-born population pressures elected officials of both parties to pursue less restrictive immigration policies. Immigrant voters sympathize with other immigrants and wish for their representatives to not treat immigrants harshly. United States Census data shows Congressman Crenshaw’s district is 21.4% foreign-born, above the national average of 13.7%. This demographic reality can be seen looking at the recent electoral history of Crenshaw’s 2nd Congressional District. In 2014, the first election after Texas adopted new congressional maps, former 2nd District Congressman Ted Poe, also a Republican, won by 38 percentage points. Four years later, after immigration came into the spotlight in both the 2016 and 2018 elections, Dan Crenshaw won the same district by only 7 percentage points. If politicians in diverse districts like Crenshaw’s continue to use tough rhetoric on immigration, they may soon be forced to give up their seats.

Critics will argue that the pre-1960s visa regime I advocate for ended due to declining wages of natives forced into competition with immigrants. A study from the National Academies of Sciences comprised of both immigration skeptics and supporters acknowledges that small numbers of low-skilled domestic workers will be displaced and see wages decline. But overall the country’s long-term GDP growth will be higher as a result of immigration due to immigrant consumption and augmenting the country’s aging workforce. Therefore, my plan will not adversely affect the nation’s economy.

From a political and policy standpoint, the temporary visa program I advocate for would be the best way for our country to fulfill our humanitarian obligations while minimizing the fears of our citizens. I recognize this solution will not satisfy everyone: immigrant rights groups will argue I am breaking up families and conservatives will say I am pushing for open borders that hurt American workers. What we need is a middle road that can solve the problem and not be broken down by “leaders” blindly spewing partisan banter. Such thinking will not only solve this issue but reunite our divided country.”