Michigan’s eighth District (MI-8) and Arizona’s fourth District (AZ-4) exist at opposite poles of the county, in states along the southern and northern borders. While Arizona flanks Mexico, Michigan is linked to Canada by its many Great Lakes. Scholarship has demonstrated that states close to the Southern border are most likely to have media that frames immigration as a Latino threat, or covers immigration with a negative tone, than states farther away (Branton & Dunway 2009, Dunway, Brandon, & Abrajano 2010). This work does not compare the rhetoric in southern border states to the rhetoric in northern border states, however. This presentation will more broadly explore the question: is immigration rhetoric (broadly defined as media, representatives’ statements, and policy discourse) in a northern border state more similar to that in a southern border state than previous work might imply? Is there something about being on a border that might shape what kinds of immigration policies a representative should pursue? As the literature suggests, we find that immigration is more salient for AZ 4 and that policies are more restrictive than in MI 8–however, rhetoric in MI 8 does frame immigration as a matter of northern border security in ways that may impact policy.

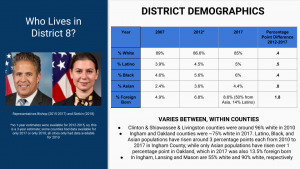

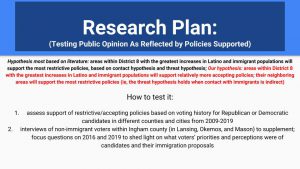

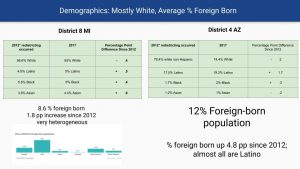

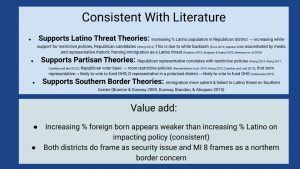

To explore this, we use the 8th district and the 4th district because not only are they both in border states, but they have some basic demographic similarities. Both districts are roughly eighty percent white, with about ten percent foreign born population (the average/slightly below average percentages when compared to the nation as a whole). Research suggests that a higher percentage of foreign born population correlates to support for more accepting immigration policy (Wong 2014). By this metric we might expect these two border states to have roughly similar, perhaps moderately restrictive, immigration policy. Indeed, both districts are red leaning, and a multitude of studies have shown that partisanship is a key predictor in support for immigration policies at both the national and local level (Casellas and Leas 2013; Ramakrishnan and Wong 2010). Furthermore, media and politicians in both districts frame immigration as a national security issue.

Despite these similarities, key differences have emerged in the reality of their immigration politics. MI-8 is now represented by a Democrat, Elissa Slotkin, who has relatively moderate views on immigration policy, while AZ-4 is represented by Paul Gosar, one of the most conservative members of congress in favor of extremely restrictive immigration policy. Gosar uses half of his tweets to discuss immigration and initiating numerous pieces of legislation restricting immigration and immigrant’s rights. In contrast, Slotkin has not initiated any bills directly related to immigration. Sometimes, she will tolerate restrictive policy–her bipartisan gun control legislation had a motion requiring a 30 second vote slipped in mandating ICE calls for undocumented immigrants who attempted to purchase guns. Furthermore, local media coverage of immigration in Arizona’s fourth district is much more ubiquitous than in Michigan’s eighth district.

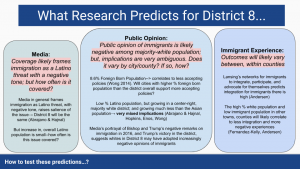

There are key differences between the districts that can explain the difference in immigration policy between them, using existing literature. First, Branton et. al (2009, 2010) show that spatial proximity to the Southern U.S.-Mexico border leads to greater newspaper coverage of immigration issues. That coverage is more likely to frame immigration as a Latino threat (Hopkins 2010, Abrajano & Hajnal 2015, Newman et. al 2018). This accurately represents the difference in coverage between AZ-4 and MI-8. Immigration is discussed in almost thirty percent of local media coverage in Arizona’s fourth district, when looking to local sources such as the Arizona Patch. This media coverage, particularly that framing immigration as a Latino narrative, can lead to more negative anti-immigrant beliefs, as proven by Abrajano and Hajnal 2015.

Second, although Michigan’s eighth district and Arizona’s fourth district have similar percentages of foreign born population, AZ-4’s immigrant population is majority Latino, whereas MI-8’s is very heterogeneous. This means that in AZ-4, there is a rapidly increasing heterogenous Latino population in a Republican district where media that frames Latinos as a threat is widespread. These are the typical conditions where the Latino threat narrative is most salient and leads to white backlash, which correlates to greater support for restrictive immigration policy and Republican candidates (Enos 2014, Abrajano and Hajnal 2015, Wong 2014)

Differences in AZ 4 and MI 8 policy are also consistent with literature on the role of partisanship, which universally correlates stronger support for Republican representatives, and Republican leadership, with more restrictive policies (Wong 2014; Casellas and Leal 2013; Ramakrishnan et al. 2010; Wong 2012). Also consistent, Slotkin as a first term rep and Democratic rep in a polarized district voted to fund the Department of Homeland Security to end the shutdown (Valenzuela 2019).

This comparison gives two potential contributions to this literature. First, the comparison implies that percentage foreign born is not as strong a metric as the percentage. Latino for predicting white backlash, and this is consistent with other studies. Second, we find that rhetoric surrounding immigration in MI 8 explicitly links immigration to security and to the northern border. In an interview for this study, Slotkin explained her belief that increased border security was necessary by saying “they never talk about the northern border. We are a border state, we do a tremendous amount of work to prevent the flow of terrorists and illegal material.” Although Slotkin does not explicitly link immigrants to a drug threat, she does focus on combating the opioid crisis–especially important in a district where opioid deaths occur at a rate 6 percentage points higher than the national average, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This is then linked to immigration by the media, according to her campaign adviser, who said they recieve calls about drugs and the border wall when “the President is angry…and Fox news is talking about it.”

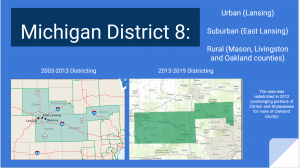

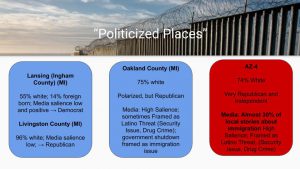

Comparing MI 8 to AZ 4 reveals the complex relationship, then, between border proximity, demographics, and securitization of immigration. MI 8, which is highly segregated, has two counties that are high minority (Lansing in Ingham county 55% white, 13% foreign born) and low minority (Livingston 96% white). From December 11, 2018 to January 31, 2019, in both the Lansing State Journal and the Livingston Daily immigration salience in media was, although it is positive when covered in the Lansing State Journal. However, Oakland county (75% white) is most demographically similar to AZ 4 (75% white). In both Oakland county and AZ 4, media covers immigration issues frequently, links the government shutdown to immigration, and frames immigration as a Latino threat linked to drugs. This suggests that the northern border may become most securitized under conditions of white backlash, where minority populations are enough to be seen as a threat but not enough to shift policy leftward.

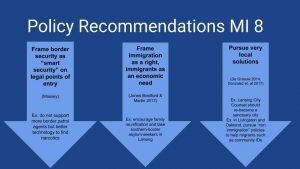

Based on these findings we recommend that both Slotkin and Gosar shift to frame border security as “smart security” on legal points of entry. Massey demonstrates that increasing militarization of the border is not effective at curbing immigration, and numerous exposes have shown that most narcotics are smuggled through legal ports of entry–so the two should both focus their efforts on improving search techniques at those ports in both the north and the south.

Slotkin should also frame immigration as an economic need, since Michigan farmers require their labor supply and Lansing has a stellar track record of integrating refugees from around the world (Slotkin, Anderson 2008). Research shows that the way politicians frame issues can have real impacts on constituent beliefs and this shift could mitigate white backlash as immigrant population continues to grow (Jones Bradford & Martin 2017). Finally, Slotkin should pursue very local solutions tailored to the segregated district. For example, Lansing City Counsel should re-issue it’s commitment to becoming a sanctuary city (which it announced and then rescinded in 2017); while more conservative Livingston and Oakland would benefit from programs that assist immigrants without increasing the salience of the issue and provoking more backlash. For example, those counties could benefit from the community ID program implemented in Princeton, NJ and other locations (De Graauw 2014, Gonzalez et. al 2017).

Gosar or a potential Democratic challenger should also pursue policies and rhetoric to combat white backlash, by not conflating Latinos with illegal immigration, by reducing unemployment, and decoupling AZ 4’s border policies from the national discussion (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015, Hopkins 2010). For a Democrat to flip AZ 4, they would need to mobilize the Latino vote. They could do this by galvanizing Latino anger, taking advantage of low Latino identification with the Republican party, and supporting a pathway to citizenship (Bowler et. al 2006, Valentino & Neuner 2017, White 2016).

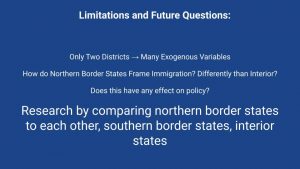

This comparison is limited in scope because it contrasts only two districts, with many exogenous variables. However, it lays the groundwork for more thorough future research investigating how northern border states might frame immigration differently than interior and southern border states. This project has shown that although existing literature accurately predicts that AZ 4 will have more restrictive policies and that immigration will be more salient compared to MI 8, our qualitative analysis shows that rhetoric in MI 8 does incorporate the northern border into understandings of immigration and security. Further research should systematically compare the media, representative rhetoric, and policies between northern border states, and compared to southern border states.