Slide 1: Evidence-Based Hypotheses

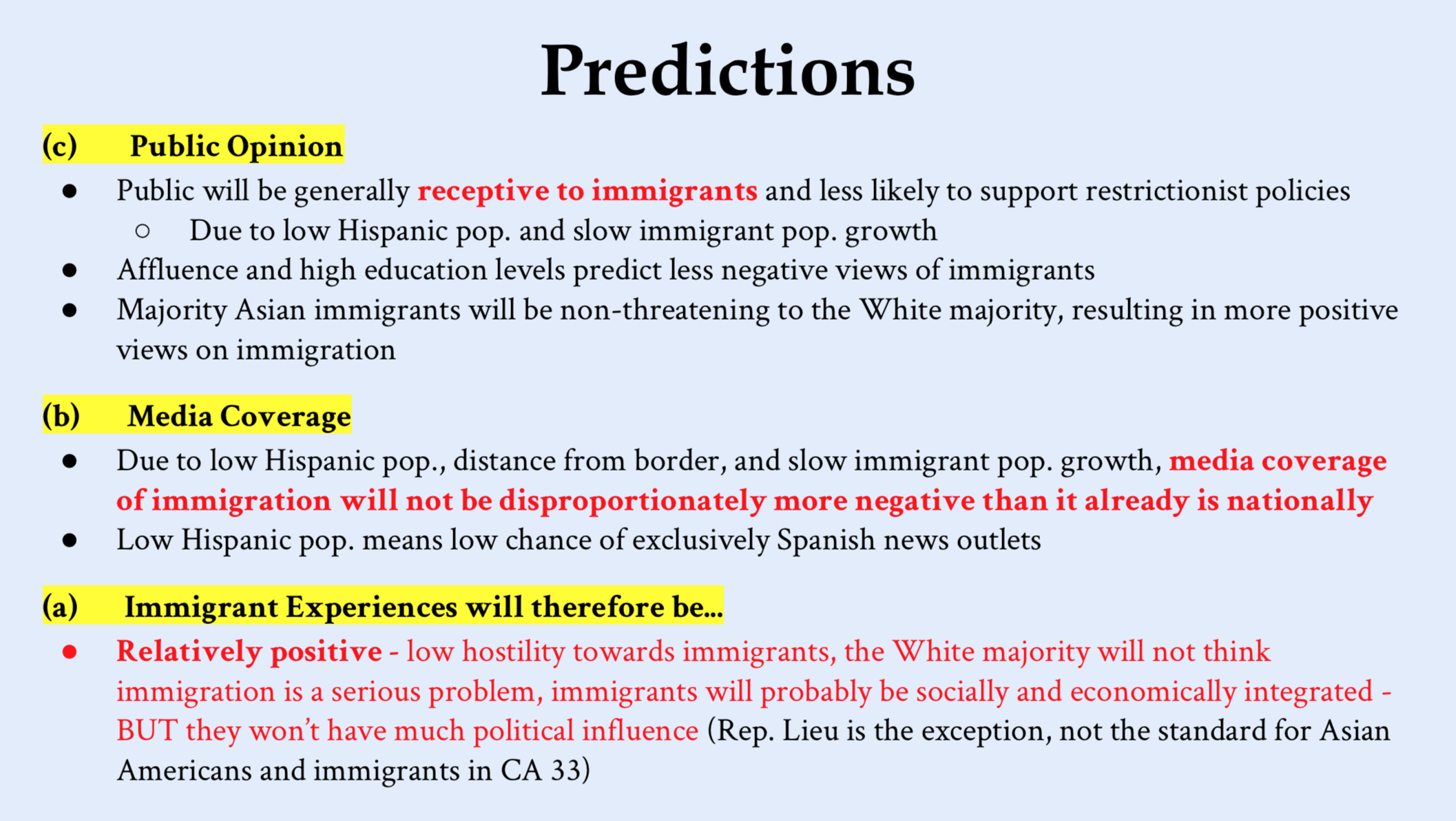

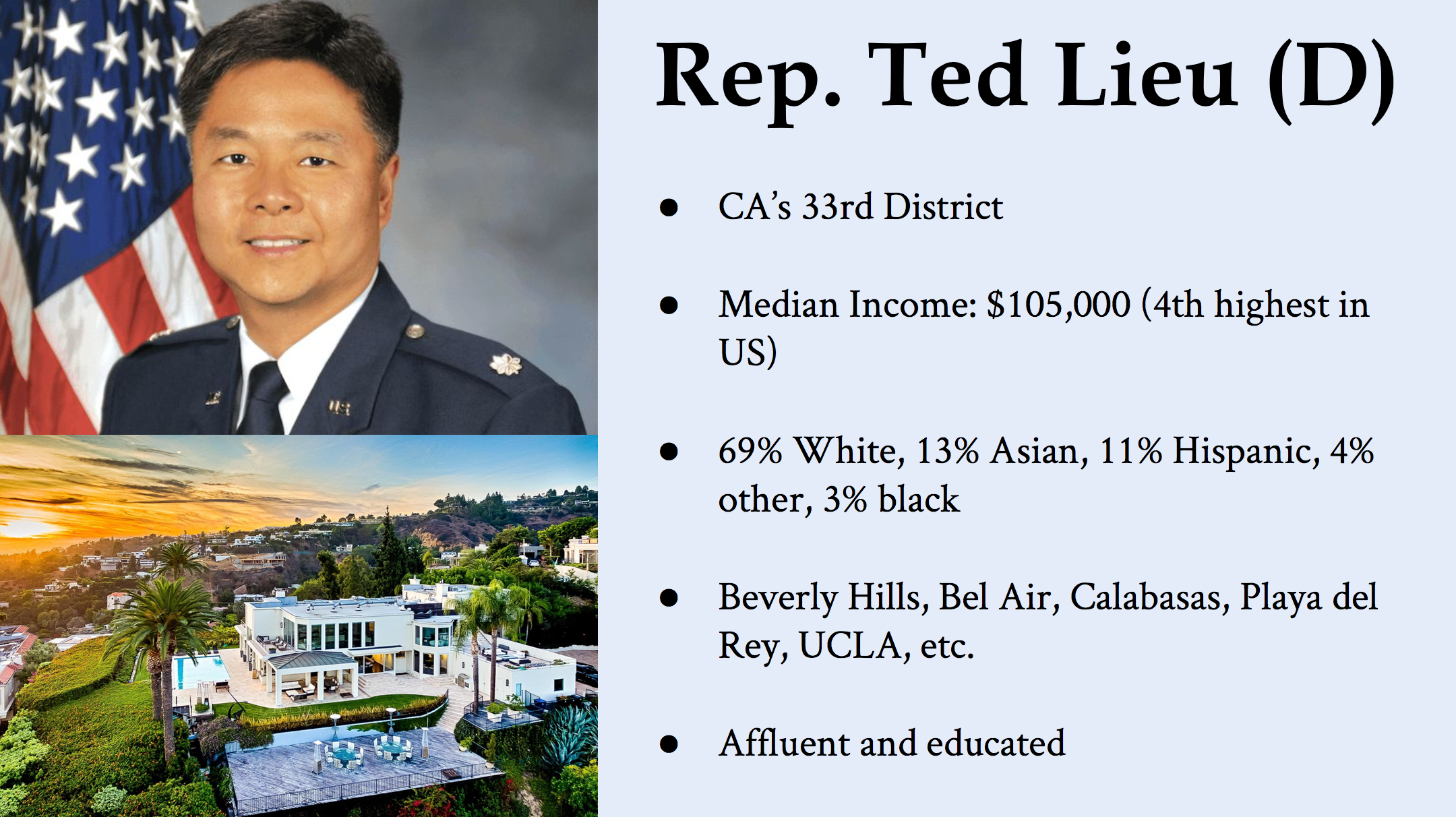

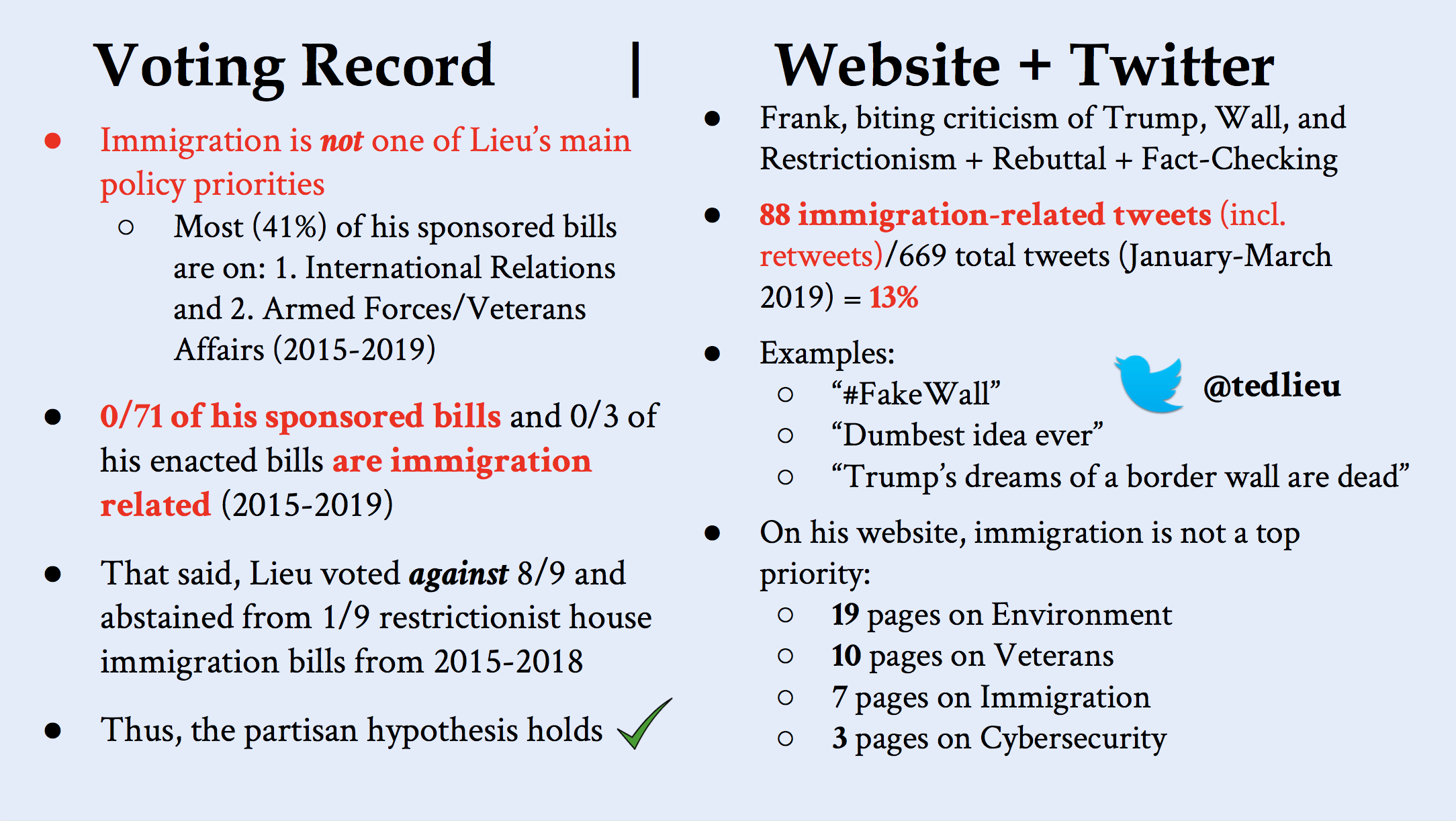

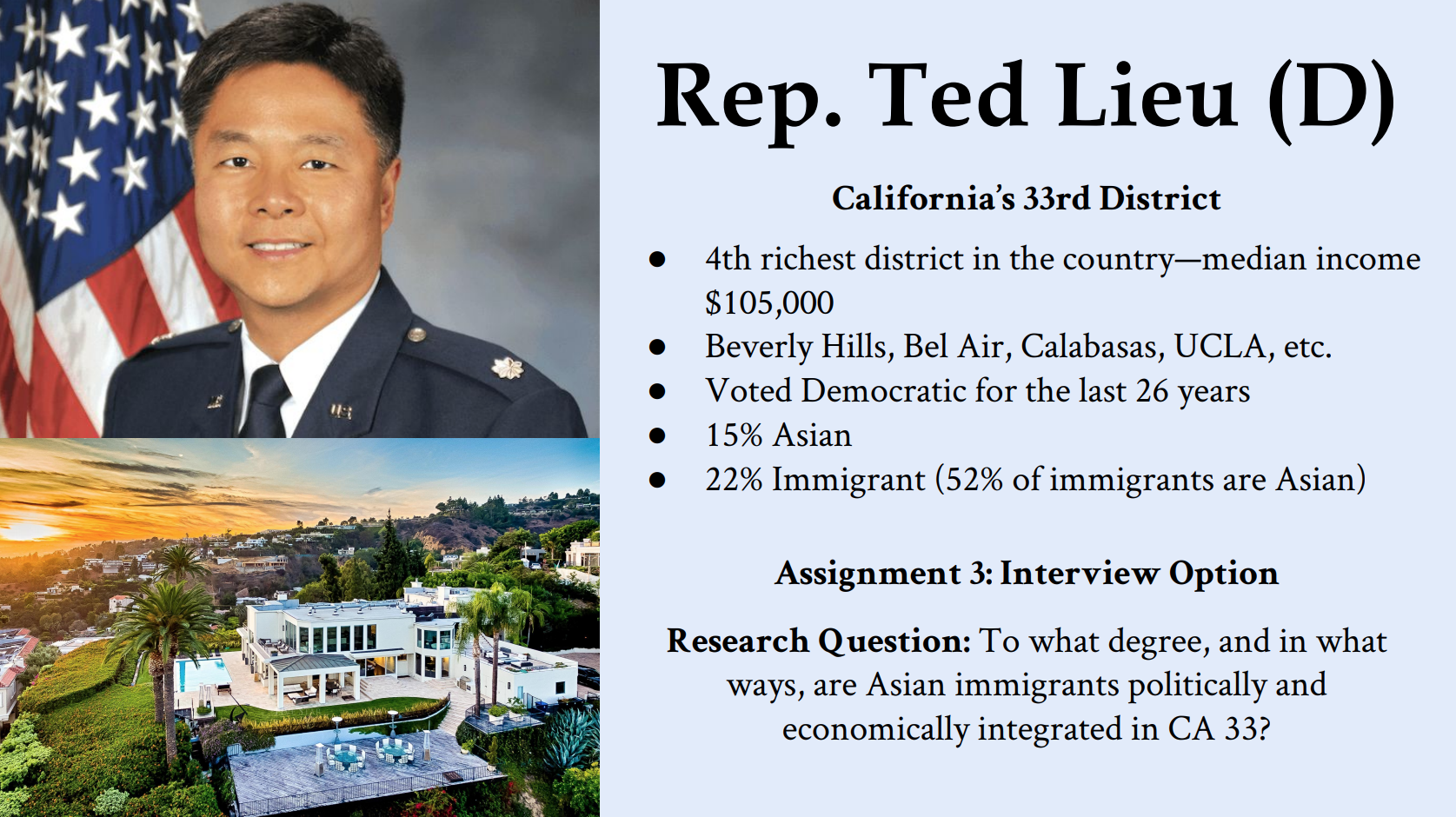

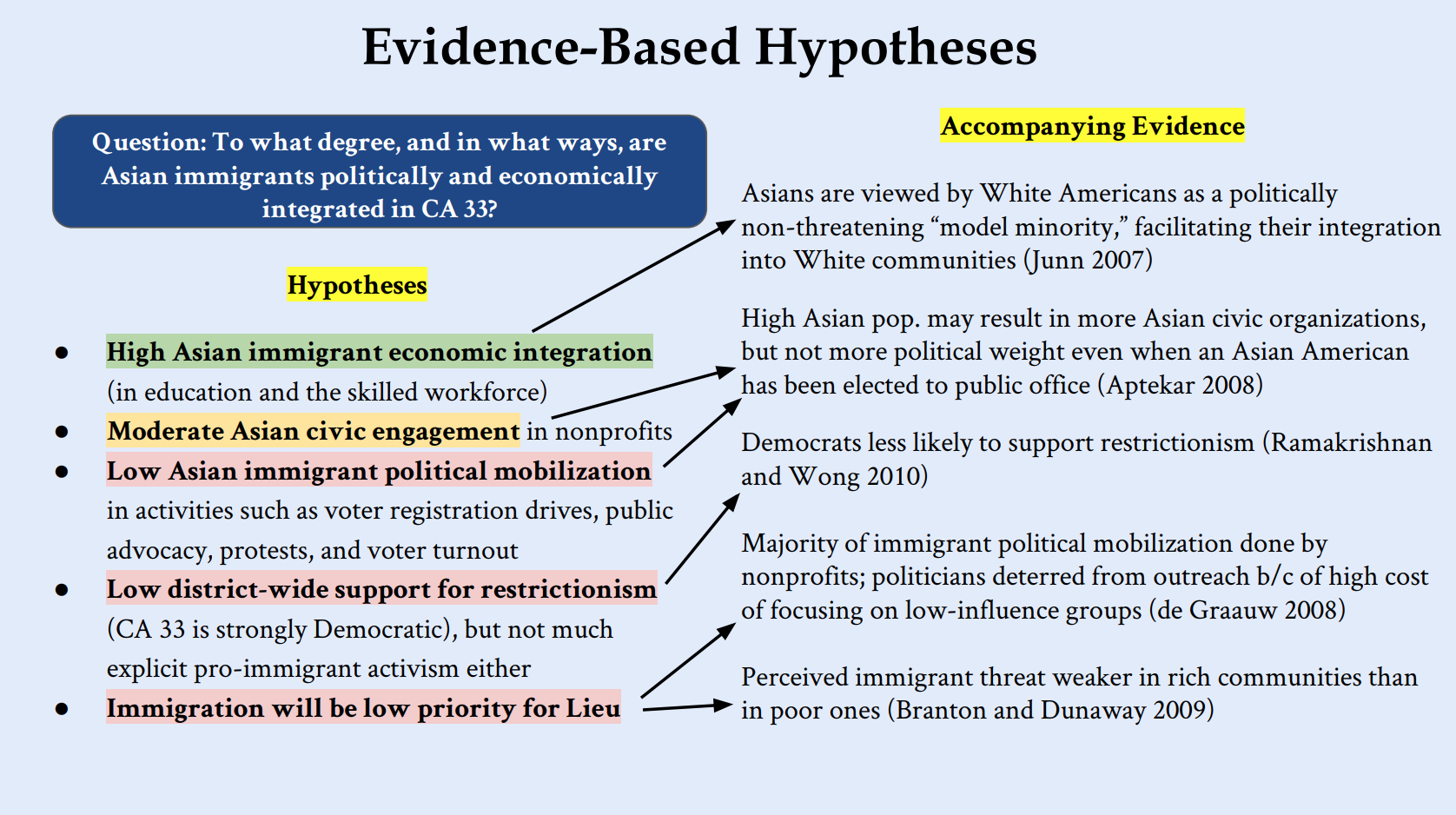

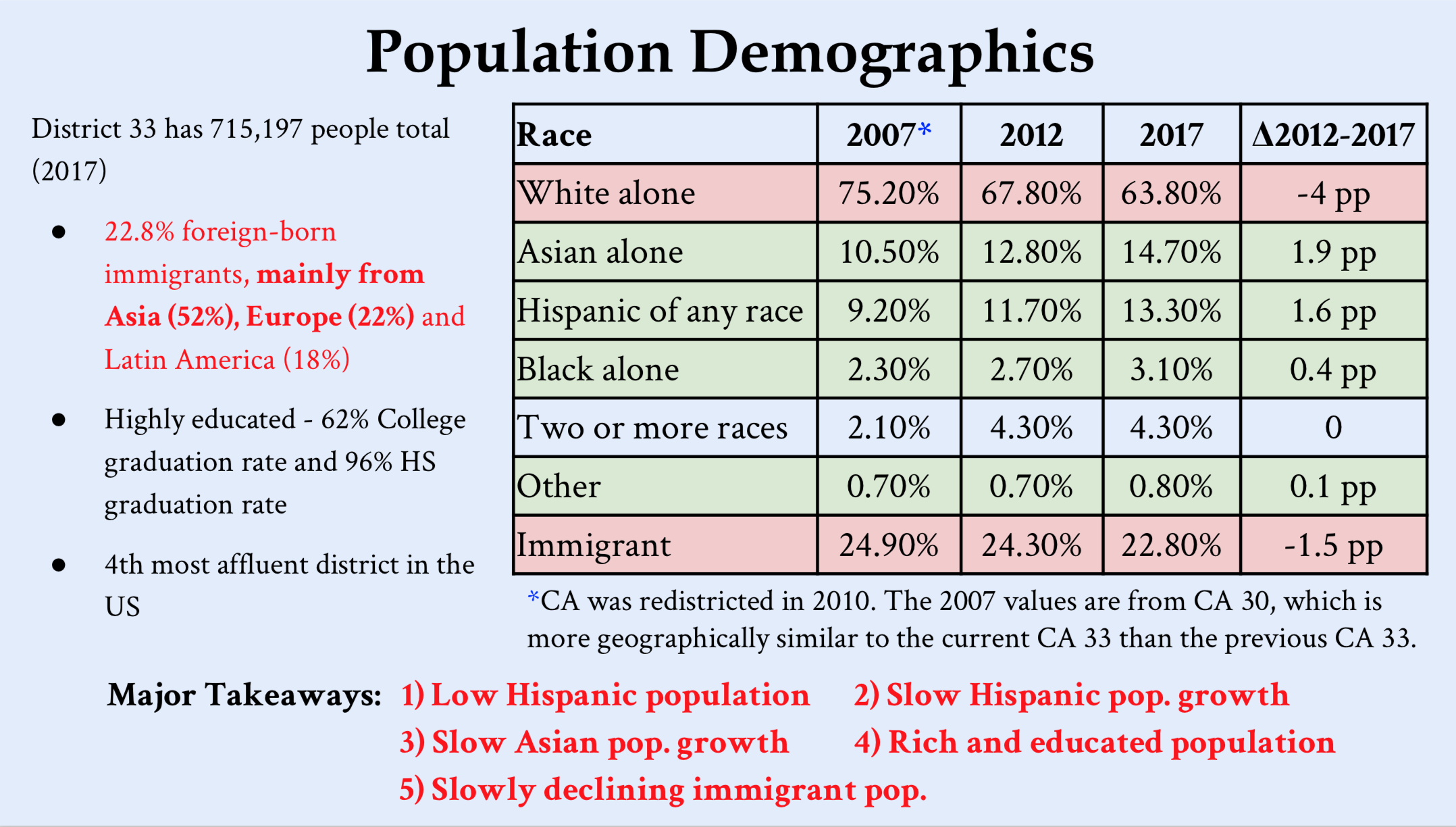

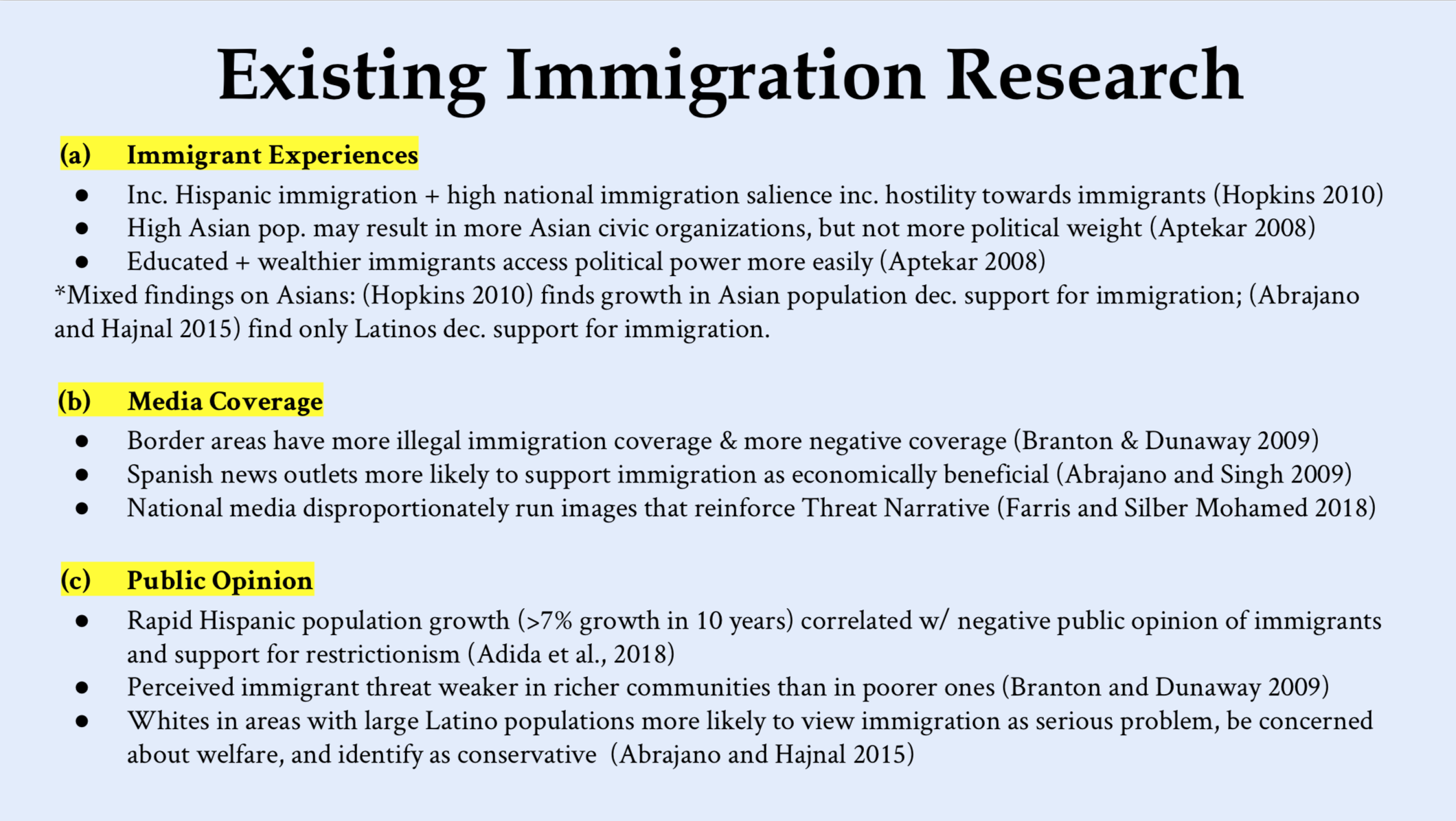

My research is inspired by the work of researcher Sofya Aptekar (2008), which assesses the political integration of Asian immigrants in Edison, NJ. My research question is: to what degree, and in what ways, are Asian immigrants and Asian Americans politically and economically integrated in CA 33? I predict that there will be high levels of economic integration because Asians are viewed as non-threatening to White people and thus can assimilate into White communities with more ease than other minorities (Junn 2007) and because the US systematically favors Asians for work visas over other races (Wong 2017). However, based on Aptekar’s findings that larger Asian populations do not translate to more political weight, I predict low levels of political mobilization through civic engagement activities like voter registration drives, public advocacy, protests, and voter turnout. Similarly to Mayor Choi in Edison, I expect Representative Lieu will not make immigration policy a top priority, especially because it’s costly to reach out immigrant groups that are less likely to vote (de Graauw 2008). Overall, I predict Asians in CA 33 will be highly economically integrated, but not very politically integrated. I further predict Representative Lieu will be anti-restrictionism but not actively pro-immigration.

Slide 2: Methodology

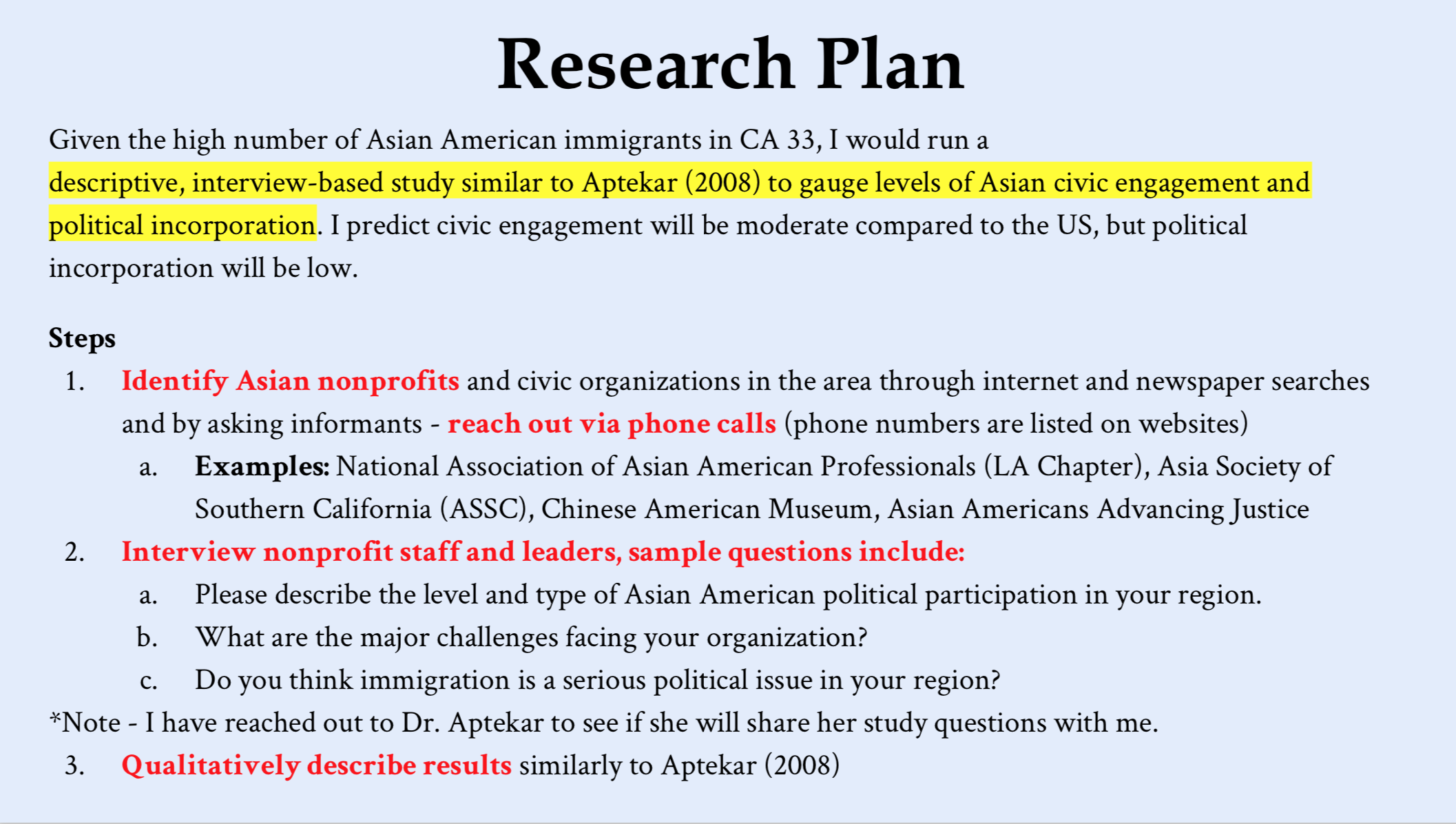

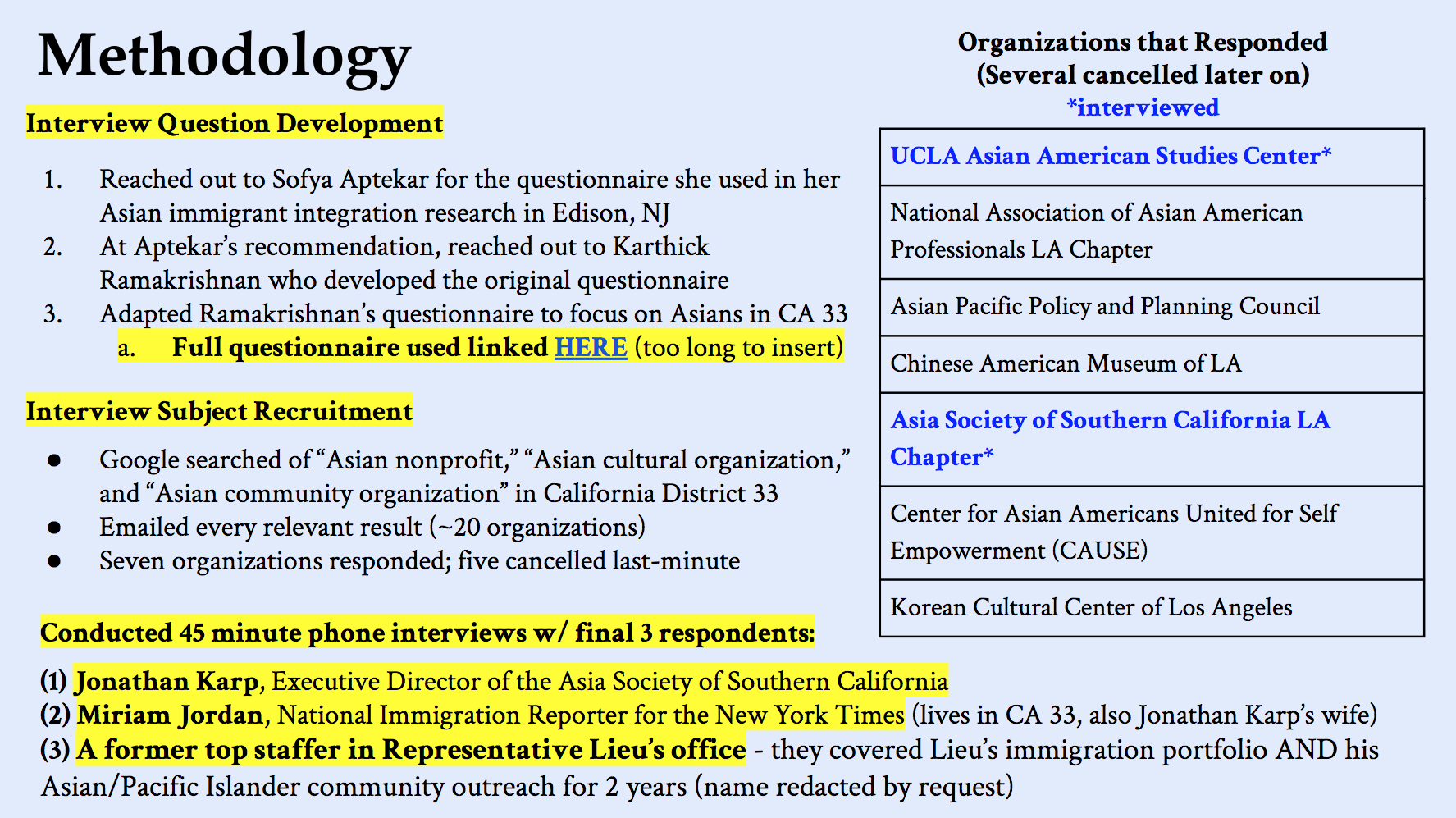

I conduct interview-based research by setting up phone calls with individuals who work in Asian organizations and nonprofits in CA 33. I begin by developing my interview questions. I reached out to Professor Sofya Aptekar at the University of Massachusetts Boston for the questionnaire she used in her research on Asian immigrant integration in Edison. She referred me to Professor Karthick Ramakrishnan at the University of California Riverside who developed the original questionnaire—Aptekar previously worked for Ramakrishnan as a research assistant and actually adapted his original questionnaire for her research in Edison. Professor Ramakrishnan kindly shared the original questionnaire he used to interview staff at immigrant nonprofit organizations, and I adjusted it to focus on Asian immigration in District 33. The final questionnaire I used is linked HERE (it is too long to insert directly). To recruit interview subjects, I googled “Asian nonprofit,” “Asian cultural organization,” and “Asian community organization” in California District 33 and emailed 22 organizations that turned up. Seven organizations responded with a staff contact for me to interview:

- The UCLA Asian American Studies Center

- The Asia Society of Southern California LA Chapter

- The National Association of Asian American Professionals LA Chapter

- The Korean Cultural Center of Los Angeles

- The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council

- The Center for Asian Americans United for Self Empowerment (CAUSE)

- The Chinese American Museum of LA

All but two, the Asia Society of Southern California and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, subsequently cancelled. My final three interviewees were:

- Jonathan Karp, Executive Director of the Asia Society of Southern California

- Miriam Jordan, National Immigration Reporter for the New York Times

- Coincidentally, Jonathan Karp’s wife happened to be the National Immigration Reporter for the New York Times; they live together in CA 33. I was able to conduct a joint interview with Karp and Jordan.

- Recent Former Staffer in Representative Ted Lieu’s Office (Name redacted)

- Referred by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center

- This top staffer covered Lieu’s immigration and Asian/Pacific Islander outreach portfolios for two years before leaving his office for another job.

- This contact requested their name be redacted due to a continuing professional relationship with Representative Lieu.

Slide 3: Findings

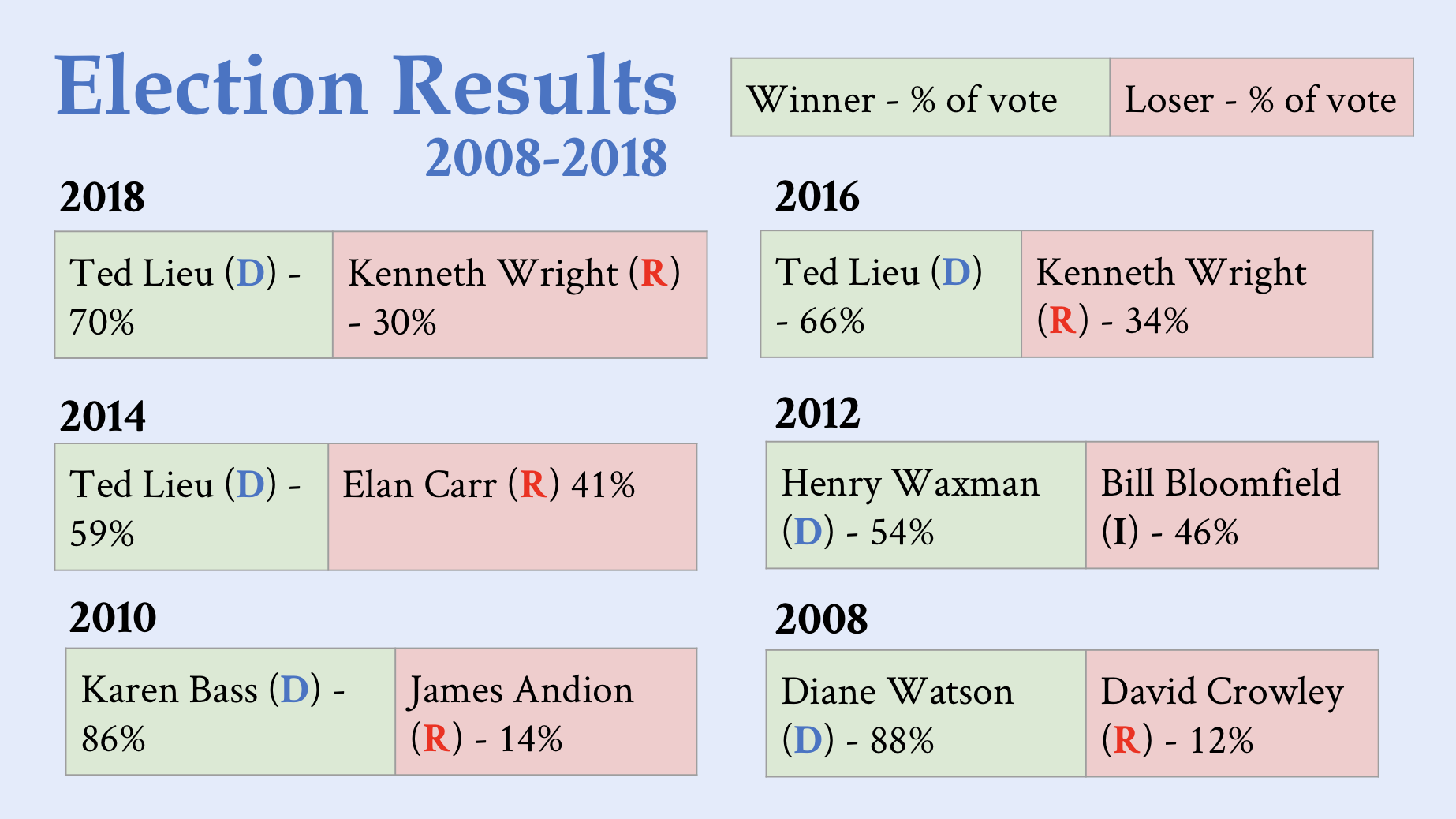

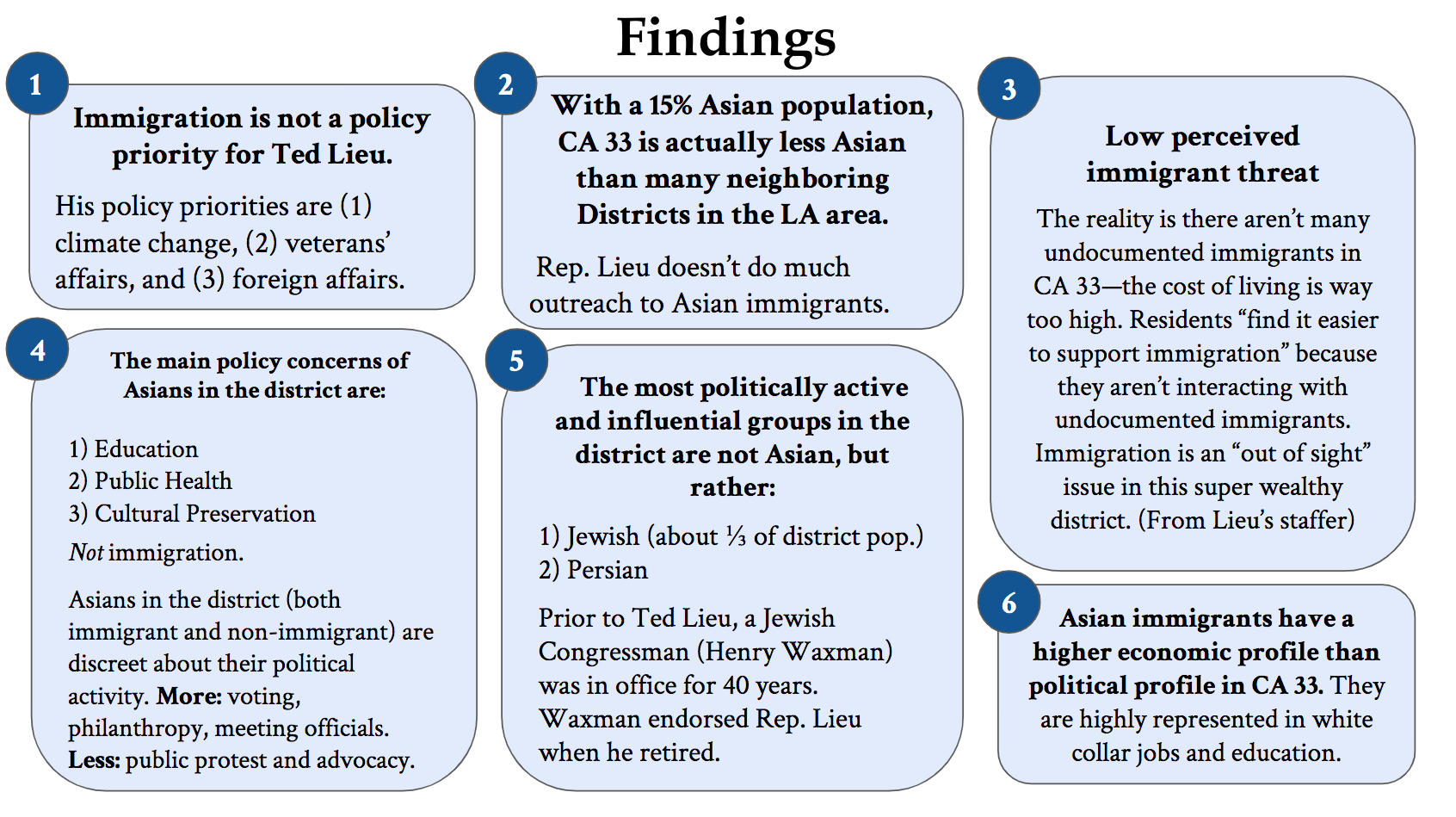

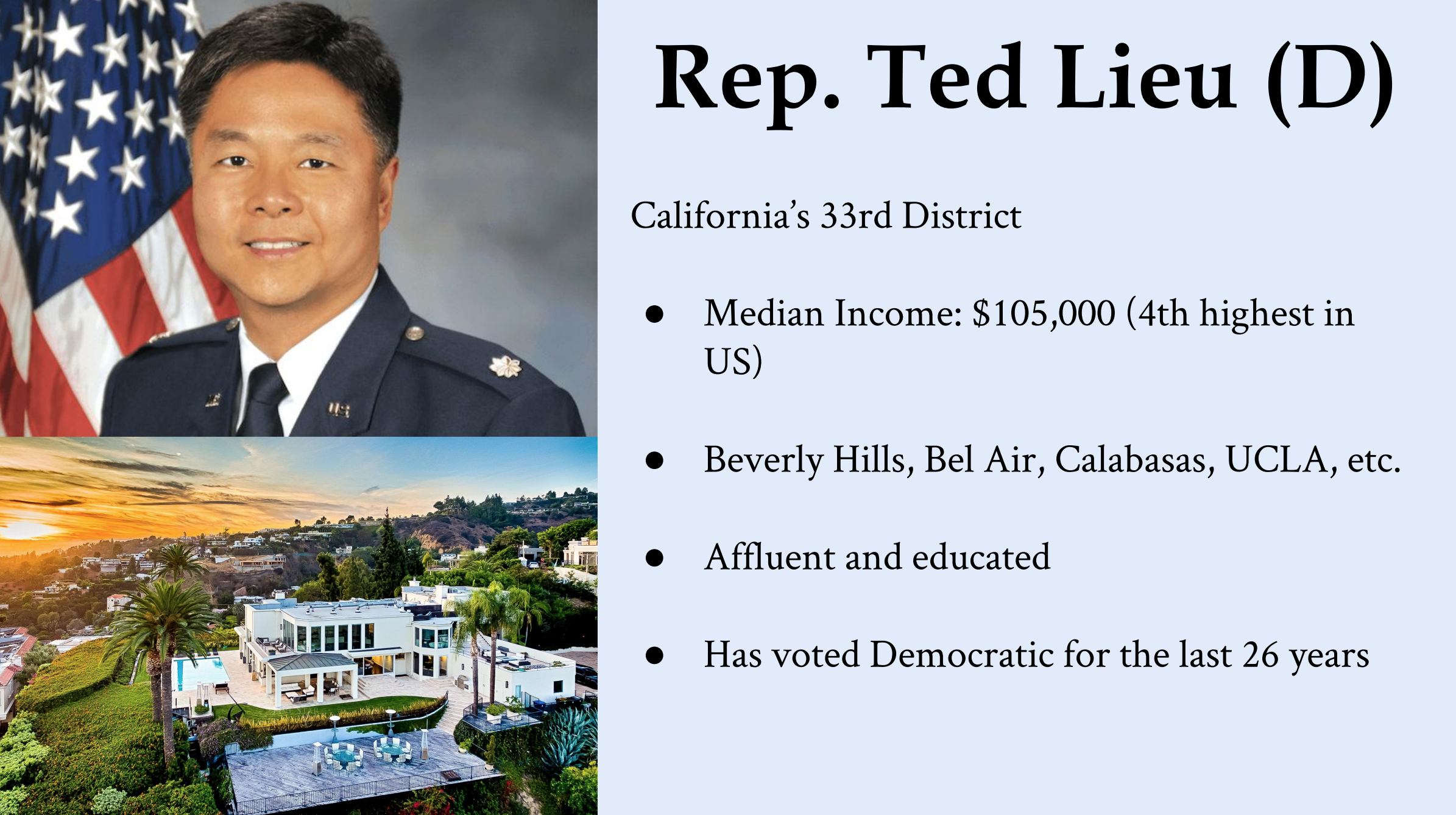

Based on my two 45-minute phone interviews with my contacts, I discovered that Asians (both immigrant and non-immigrant) are not considered a sizeable portion of the CA 33 population, especially compared to other districts in Southern California. As a result, immigration policy and Asian community outreach are not top priorities for Representative Lieu. My interviewees agreed that Asian immigrants are not a strong political force in the district. They all stated that the most politically influential ethnic groups in the district are Jews, who make up about a third of the population, followed by Persians. District 33’s previous Representative, Henry Waxman, was Jewish and in office for forty years before voluntarily retiring. When Waxman retired, he endorsed Representative Lieu. According to Lieu’s former staff member, he certainly puts more effort into maintaining constructive relations with the Jewish community than the immigrant or Asian communities. My interviewees also emphasized that CA 33 is deeply shaped by its enormous wealth—it is the fourth richest district in the country. Because the cost of living is so high, undocumented immigrants are, for the most part, priced out of the area. The small undocumented population is mostly composed of students attending universities in the district (UCLA, Pepperdine, community colleges). Consistent with research conducted by Branton and Dunaway (2009), it appears the perceived immigrant threat is lower in wealthier communities. Lieu’s former staffer added that the undocumented immigration is a very “out of sight” issue for the wealthy, and the spatial separation from undocumented individuals makes it easier for residents to claim they support immigration. As long as isn’t an issue that is proximate to their communities, they can comfortably denounce restrictionism with the knowledge that low-income immigrants can’t afford to live in their neighborhoods anyways.

Slide 4: Conclusions

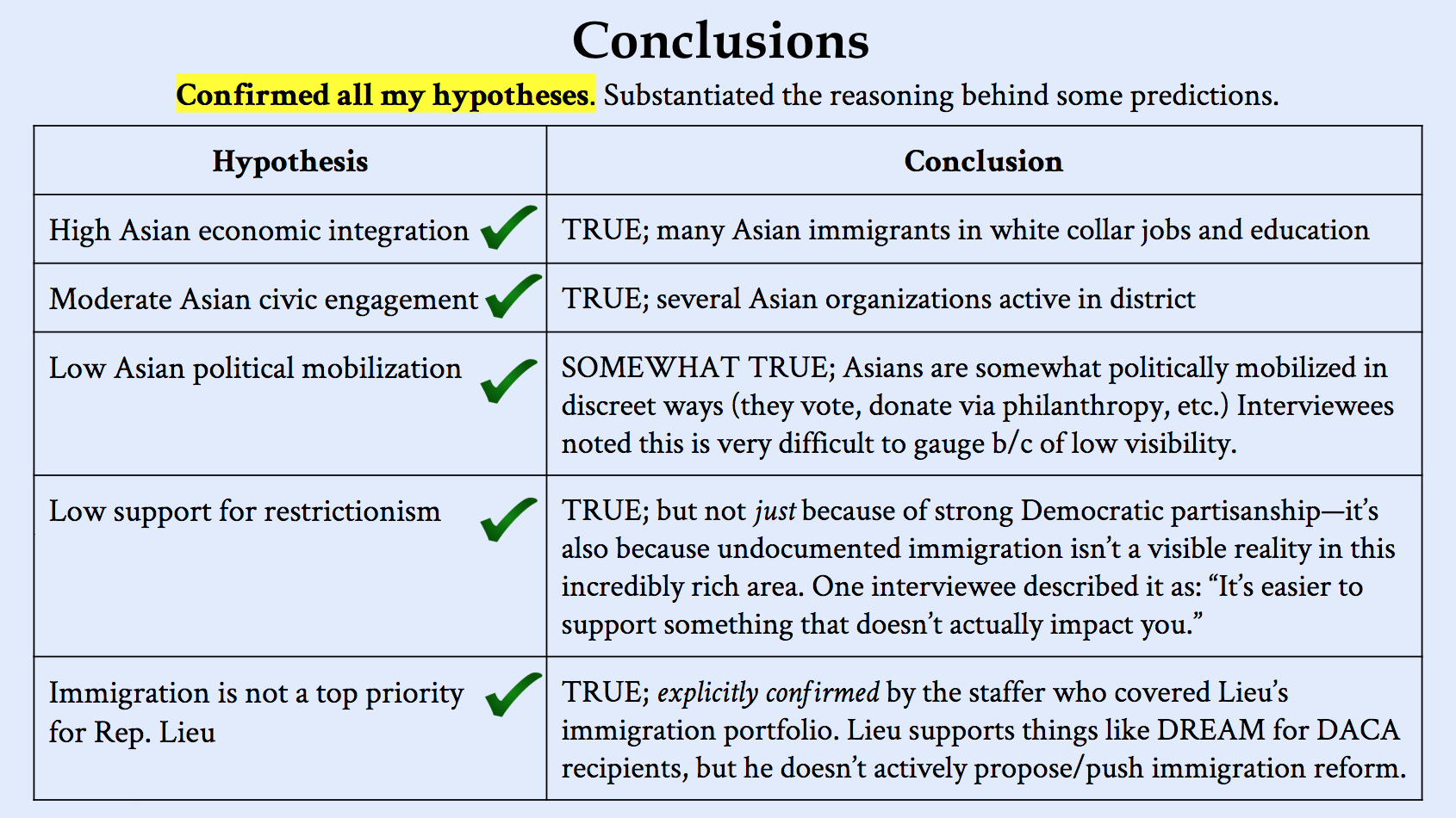

The findings from my interviews confirm my hypotheses and add missing mechanisms behind my predictions. First, I received explicit confirmation from Lieu’s former staffer that immigration isn’t a top priority for the Congressman and the district. I learned this is in part because there aren’t that many undocumented immigrants in the district due to the high cost of living. I was also told that Representative Lieu really doesn’t emphasize his Asian immigrant heritage when he presents himself. Instead, he focuses on his airforce service and commitment to strong foreign policy and veterans’ welfare (the largest VA in the country is located in the district). I received further confirmation of my hypothesis that Asians immigrants are highly economically integrated into white collar professions and higher education, but they are not very politically integrated and engaged. The types of political activity they do selectively participate in is far more discreet than visible. It takes the form of voting, donating, and meeting with officials rather than publically protesting, demonstrating, or advocating for certain policies. Lastly, I confirmed my hypothesis that the district is broadly against restrictionism. However, I discovered this is not just because of its democratic partisanship, but also because the perceived immigrant threat is lower in wealthy communities with low undocumented populations. In other words, it could be the case that residents would not support a pathway to citizenship if the naturalized citizens they theoretically support were capable of moving into, rather than being priced out of, their district’s wildly expensive neighborhoods.

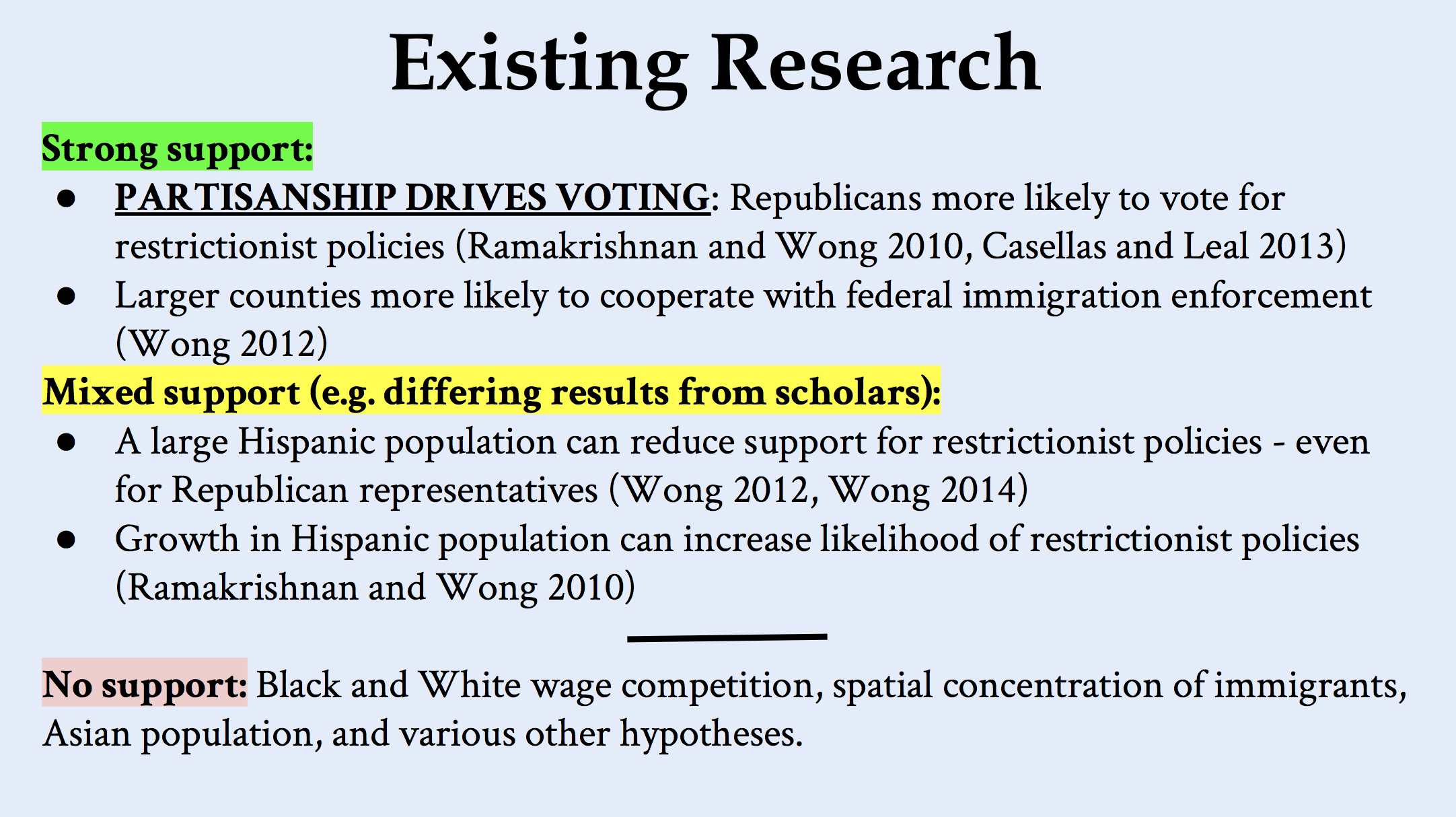

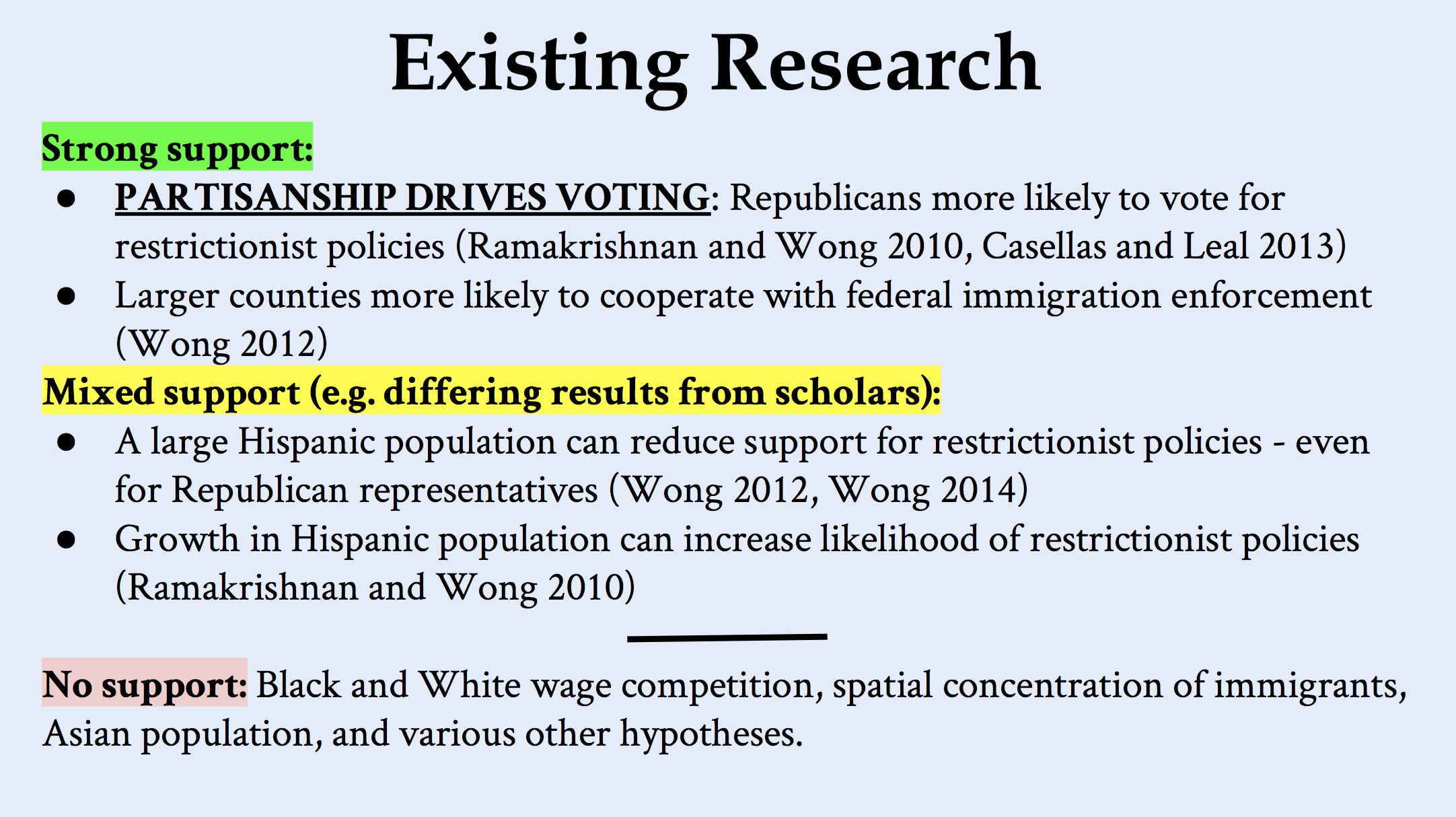

Slide 2: Existing Immigration Research

Slide 2: Existing Immigration Research