Summary:

This op-ed focuses on how Representative Adriano Espaillat can best represent his Northern Manhattan congressional district on issues of immigration, in particular in light of recent hostility from the Trump administration. It centers on the remarkable ethnic diversity within the district that has in the past contributed more to source of competition than a shared identity as immigrants. But while New York City politics may be predisposed toward ethnic competition, the city also has a long history of immigrants working to help other immigrants. I suggest that local politicians and organizing leaders must work together to bridge these differences and build coalitions over common agendas. Though this will undoubtedly require sustained outreach across communities, only by working together and promoting the integration of currently marginalized groups will we achieve progress on creating more welcoming and inclusive communities.

Responding to Trump: Can Immigrant Identity Prevent Subgroup Fragmentation?

President Donald Trump’s latest thoughts on immigration proposal, set to be unveiled today, threatens to upend the norms that have guided this country’s immigration system has functioned over the past decades. Should the proposals eventually become law, they will sharply curtail the ways in which people of other nations seek better lives in the United States. This will in particular affect the millions of immigrants in cities like New York, who live in ethnic enclaves where family connections are the main pathway to residence and ultimately citizenship.

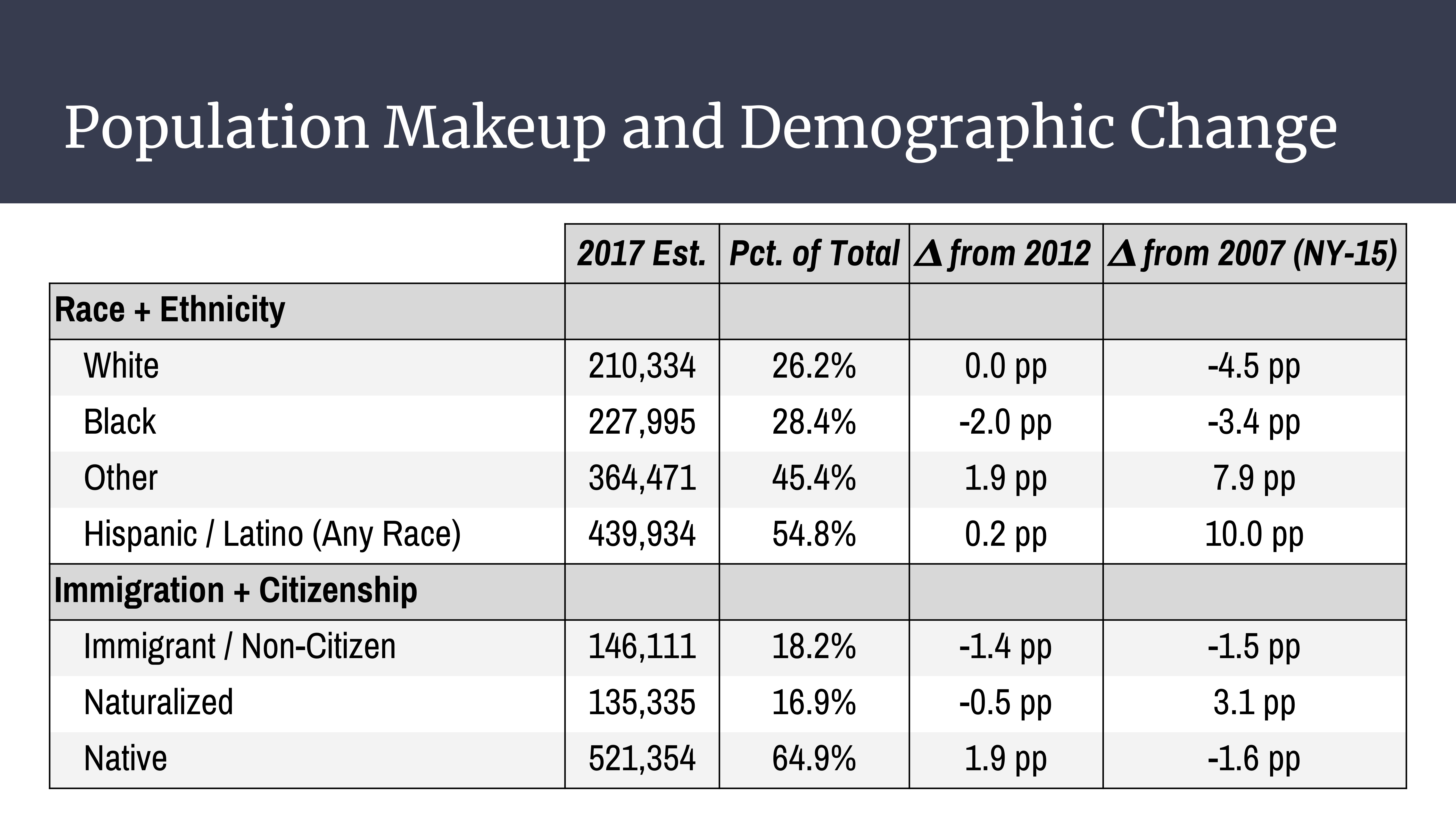

Let’s look at one such example: New York’s Thirteenth Congressional District, composed primarily by Upper Manhattan, is more than a third foreign born, while close to sixty percent of the district’s residents speak a language other than English at home, according to the most recent Census estimates. For many there, immigration issues are a top priority. In the time I spent in the district, I learned that a deep sense of fear pervades the district. Not only does the undocumented population live with the constant dread of deportation, but legal residents as well worry about their futures under the current administration.

To what degree are they supported by local politicians? It depends who you ask. While more well-connected immigrant communities enjoy the full-throated support of local politicians, others, such as the Mexican immigrants of East Harlem, are not so lucky. These communities suffer from regular mistreatment and “broken promises” as a result of their lack of representation, according to Melina Gonzalez, immigration outreach organizer at LSA Family Health Service, a local nonprofit organization. At the same time other national groups, such as West Africans, feel disconnected entirely from the political system, according to François Nzi, the founder of a tutoring and coaching service for immigrant youth, and himself originally from the Ivory Coast. Despite the fact that the current representative in the U.S. House was a formerly undocumented Dominican, many still feel unembraced by the political elite. And while individual communities inhabit adjacent, or even shared spaces, there is little sense district-wide of banding together as a unified immigrant voice.

Part of that is just New York City politics, and its history of ethic competition. On a surface level, given the long tradition of identity politics in New York City, it would be only natural to claim to speak for one’s own ethnic group. But on a more structural level, however, historians such as Nancy Foner, a professor of sociology at CUNY, have long maintained that “In New York, ethnic competition is a fact of life.” Foner, quoting the UCLA professor Roger Waldinger, argues that the “politics in the city ‘presents newcomers with a segmented political system, organized for mobilization along ethnic group lines, and a political culture that sanctions, indeed encourages, newcomers to engage in ethnic politics.’” Cooperation and joint action, then, are the exception rather than the norm, a reality that may be harming the immigrant cause overall.

The solution to that problem, however, is clear. In order for local political leaders to better serve their constituents on the issue of immigration, they must work toward creating cross-cutting ethnic coalitions to support an immigration-focused agenda. In doing so, they have much to draw on: New York City has a long history of managing its unique diversity. As Mary Waters & Philip Kasinitz summarize in a recent essay: “if New York seems perennially beset by small ethnic struggles, its diversity of groups, its complex quilt of overlapping interests and alliances, and the broad acceptance of the idea that ethnic succession, if not always pleasant, is both legitimate and inevitable have generally prevented city-engulfing racial or ethnic conflagrations.” Successful outcomes, they argue, are a result of cooperation that happens when different groups can realize that they’re on the same team.

This too, has been an approach previously effective in New York. A comparative study of several U.S. and European cities credits the successful outcomes on measures of immigrant integration to be due, in part, to the dense presence of immigrant-oriented organizations that “have been able to find common ground and articulate common agendas focused on issues affecting many disadvantaged immigrants … Organisations actively engage in coalition building to pool their staff skills, membership bases, and other organisational resources.” That paper links the increasing influence of immigrants in local New York politics to their ability to identify and mobilize over shared group interests.

Only time will tell how much of an impact Trump’s latest proposals will have on immigrant interests in New York and around the country. But those who wish to fight back must focus on fostering collaboration and unity among the various ethnic identities jostling for influence. The actual implementation of this goal will require a combination of bottom-up and top-down measures: local organizers should continue to focus on increasing measures of civic engagement, but elected officials must at the same time make a coordinated effort to incorporate marginalized communities into political processes. Representative Espaillat is smart to draw on his Dominican heritage to underpin his support for immigrants, but he must at the same time be wary of relying only on his personal narrative to the exclusion of the full diversity of his district.