Summary

Congressional Representative Juan Vargas, who represents the southernmost parts of California along the U.S.-Mexico border, should embrace the Democratic Party’s liberal stance on immigration and continue to prioritize pro-immigration policies in order to appeal to his broad voting base. Median voter theorem tells us that representatives should appeal to the median voter in their district, which for Vargas’s case is a voter with pro-immigration views, regardless of their ethnicity or race. Therefore, Vargas would be wise in prioritizing immigration as one of his policy issues and taking a strong expansionist immigration view, keeping in line with the Democratic Party’s current stance. In truth, he is already well on his way there–his co-sponsored bills, social media, and rhetoric demonstrate a commitment to immigration that he should continue to pursue, and that the rest of the Democratic Party would do well to follow.

Op-Ed

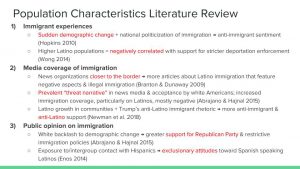

For a long time, immigration was seen as an issue that cross-cut traditional cleavages to create unlikely bedfellows on both sides. Daniel J. Tichenor’s 2009 article “Navigating an American Minefield: The Politics of Illegal Immigration” discusses the historical stances on immigration, as left-leaning cosmopolitans banded together with pro-business interests to support expansive immigration policies, whereas Democratic economic protectionists—namely union workers—teamed up with cultural protectionists to favor restriction of immigration numbers and rights. However, immigration has increasingly become less cross-cutting and more strictly wedded to the divisions of traditional partisanship—that is, Democrats support pro-immigrant policies, and Republicans seek to restrict immigrant freedom and entry, as recent Congressional actions and numerous political science studies find. In order to maintain their base of support, Democrats should support their party’s stance on immigration and the importance of expansion. Particularly in the case of district CA 51, which encompasses parts of San Diego and Imperial County right on the U.S.-Mexican border, Congressional Representative Juan Vargas should embrace the Democratic Party’s increasingly liberal stance on immigration and continue to prioritize pro-immigration policies in order to appeal to his broad voting base.

A rapidly increasing body of literature finds that Democratic districts and representatives tend to have more pro-immigration policies, whereas Republican Members of Congress are likely to espouse more anti-immigration ideals. As Tom Wong argues in his 2017 book The Politics of Immigration: Partisanship, Demographic Change, and American National Identity, partisanship has become the defining determiner of representatives’ votes on immigration. Through an examination of federal votes on immigration-related policies, Wong concludes that House Representatives’ voting records have “entrenched perception that Democratic legislators will stand on the side of more inclusive immigration reforms and against restrictive immigration policies” (Wong 15). In their 2013 paper, Jason Casellas and David Leal further develop Professor Wong’s discussion of partisanship in immigration policymaking, supporting the idea that a strong Democratic presence leads to more inclusive immigration policymaking. Through statistical analysis, Casellas and Leal find that “partisanship is the only consistent factor across votes and chambers,” and that Latino population was associated with more votes in the House compared to the Senate (Casellas & Leal 48).

Polarization between Democrats and Republicans has only been deepened by the ease with which voters can choose a side on immigration—there are starkly defined lines between the two parties, and therefore the choice for many Americans is clear. However, in an ideal world, the Republican Party would also embrace immigration and the benefits that immigrants bring to American society. Beyond the incommensurable benefits of diversity of cultures and backgrounds for natives and nonnatives alike, immigrants also produce tangible economic benefits. In their 1995 study, economists Rachel M. Friedberg and Jennifer Hunt find that contrary to popular belief, empirical evidence does not support the idea that “immigrants have a large adverse impact on the wages and employment opportunities of the native-born population of the receiving country.” Natives do not suffer significantly due to increased immigration, even when they have closely related or substitutable fields of work. Additionally, a 1994 report by Michael E. Fix and Jeffrey S. Passel finds that contrary to public perception, immigrants pay significantly more in taxes than they receive in services. However, if the Republican Party is unwilling to accept these truths, the Democratic Party and its representatives would do well to hold even more firmly to their expansionist immigration views, and uphold them proudly. The cost of increased polarization pales in comparison to the human dignity of immigrants and the benefits they and their host country would receive as a result.

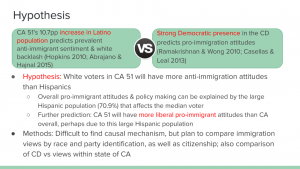

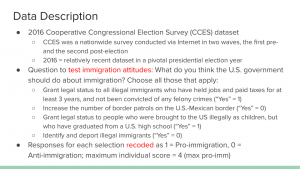

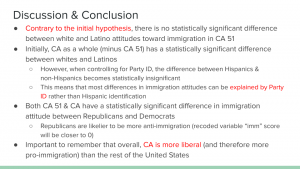

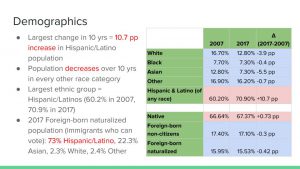

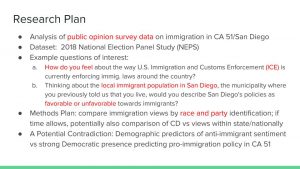

These increasingly entrenched immigration stances create an action plan for Representative Juan Vargas that emphasizes pro-immigration attitudes and a prioritization of immigration issues in his policy and platforms. Representative Vargas’s median voter is pro-immigration, and the median voter theorem proposes that representatives should cater to the district’s median voter preferences in order to capture the broadest possible base of support. CA 51’s median voter is Hispanic, as the district boasts a Hispanic population of 70.9% and a substantial 10.7 pp growth in the Hispanic population over the past 10 years. According to a 2008 Pew Research study by Lopez and Minushkin, Hispanic voters traditionally favor the Democratic Party and its pro-immigration policies. Furthermore, Professor Wong’s 2014 paper “The Politics of Interior Immigration Enforcement” found that higher Latino populations are negatively correlated with support for increased interior enforcement. Secondly, in my own initial research, utilizing the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES) dataset, I found that regardless of ethnicity, residents of CA 51 have positive pro-immigration views, since there is no statistically significant difference between Latino and non-Latino attitudes toward immigration. It is therefore in CA 51 and Representative Vargas’s best interests to represent the median pro-immigrant constituent.

In truth, Representative Vargas already has quite a stellar record on these fronts. The largest percentage of his sponsored and co-sponsored bills—19% of them—is on the topic of immigration. Immigration is a clear priority for him, evident from his social media cover photos and website that emphasize solidarity with DREAMers and immigrant veterans. Furthermore, a large 15% of his total tweets from January to March of this year were about immigration, and 100% of them adopted a positive tone about immigration. In speaking to news outlets, he also frequently underlines his commitment to immigration reform, stating that “comprehensive immigration reform will improve border security while treating immigrants with human decency” in a recent interview with the San Diego Union Tribune.

America may no longer be the land of cross-cutting cleavages, where Democrats and Republicans can stand together on the issue of immigration, depending on what interests they pursue and prioritize. However, this is not necessarily a bad phenomenon. Rather, Democrats and Democratic representatives should hold the ideals of pro-immigration ever more strongly, and follow the example of Members of Congress like Representative Juan Vargas, who should continue to pursue pro-immigrant policies in order to appeal to his expansionist voting constituents.