Summary:

Based on my Assignment 3 research, I found that negative attitudes towards immigrants in LA-3 did not seem to be based on actual immigrant/Latino population size/growth. This was due to the extremely small population of immigrants present in my region. Instead, I theorized that negative attitudes could be largely informed by anti-immigrant rhetoric from politicians (at the national and local level) as well as in the media. The scope of the studies we’ve examined doesn’t quite extend to my population of interest (White residents of LA-3). For instance, Abrajano and Singh examine the correlation between individual and media attitudes within Latinos, not on Whites (2009). Meanwhile, Newman et al. report the link between Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric and increased salience, but don’t explicitly discuss its effect in the near-complete absence of immigrants (2018). However, I believe that both of these effects could potentially extend to the local population and inform their immigration views. If this is true, I theorize that the impersonal means of acquiring these views means that negative attitudes may be malleable (as compared to negative impressions formed through actual contact). Based on this, I recommend to a local advocacy group, the St. Frances Cabrini Immigration Law Center, that they increase education of White locals in the area. Work by Adida et al. and Enos encourages the idea that exposure to and education about immigrants could potentially increase inclusivity and support. Thus, I recommended increased local education, with the hopes of fostering a friendlier community for immigrants.

Full report:

Advocacy Recommendation: Promoting Local Inclusivity Through Education

One of the hallmarks of President Trump’s bid for the Republican nomination was his staunchly anti-immigrant rhetoric. With his visit to Southern Louisiana impending, as per Congressman Higgins’ most recent press release, one might worry about the President re-inflaming latent anti-immigrant sentiment in the region. However, after examining the demographics and public attitudes towards immigration in Louisiana’s 3rd congressional district (LA-3), I believe that it may be possible to, at least to some degree, turn around prevailing local anti-immigration attitudes. In order to create a more hospitable environment for immigrants, it is necessary to not just help immigrants on the road to naturalization, but also to educate the surrounding community, who currently lack positive representations of immigrants. Current anti-immigrant opinions in the district appear to be informed by passive consumption (i.e. political and media cues) rather than by negative experiences with immigrants: by supplying positive information about immigrants to local residents, it may be possible to amend their current views on immigrants and foster a more inclusive community.

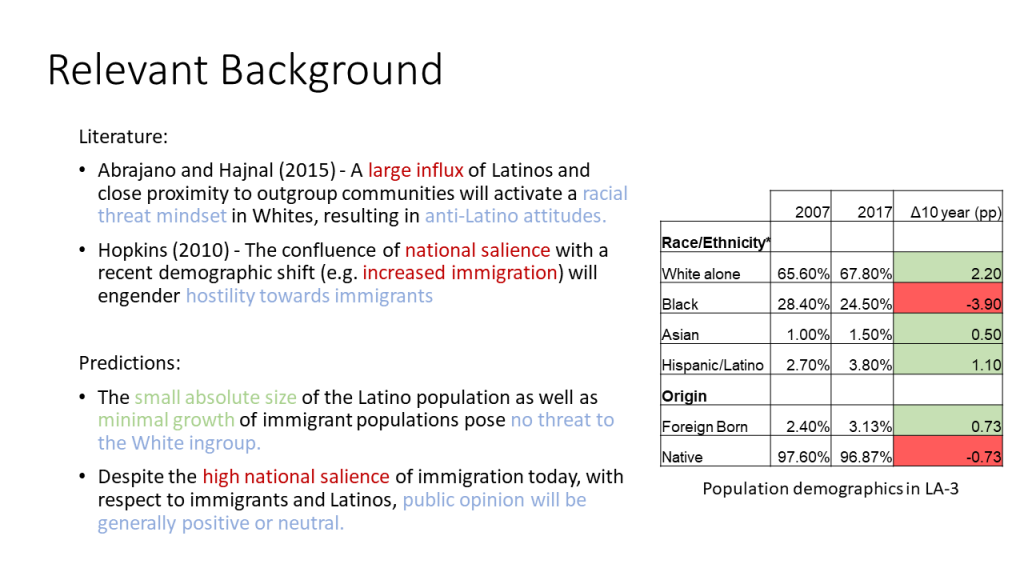

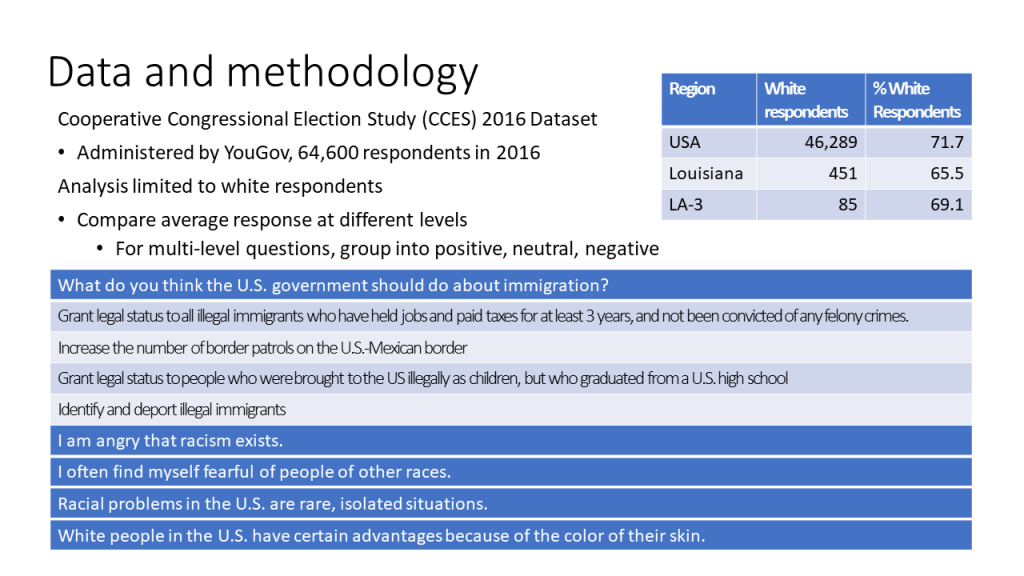

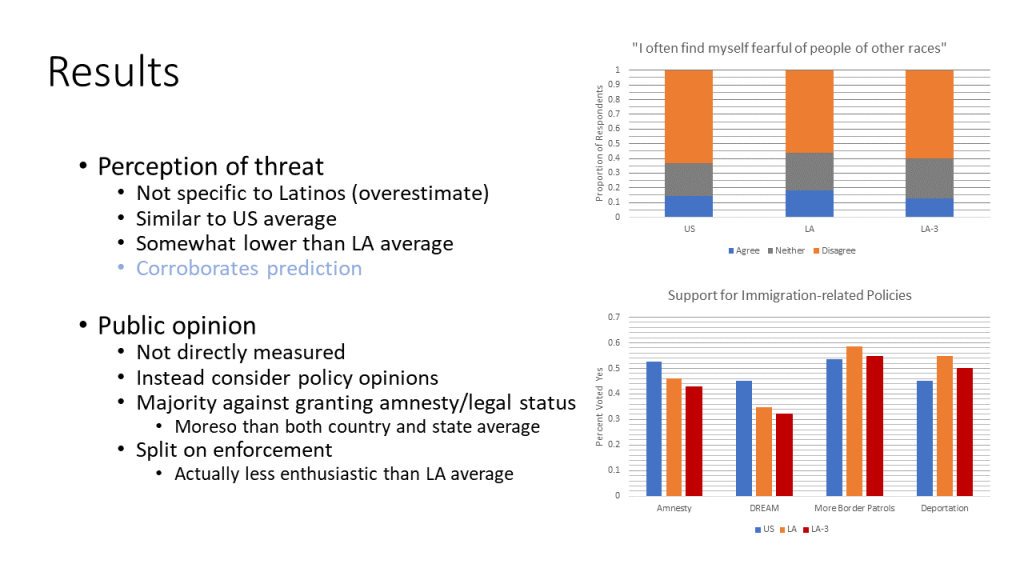

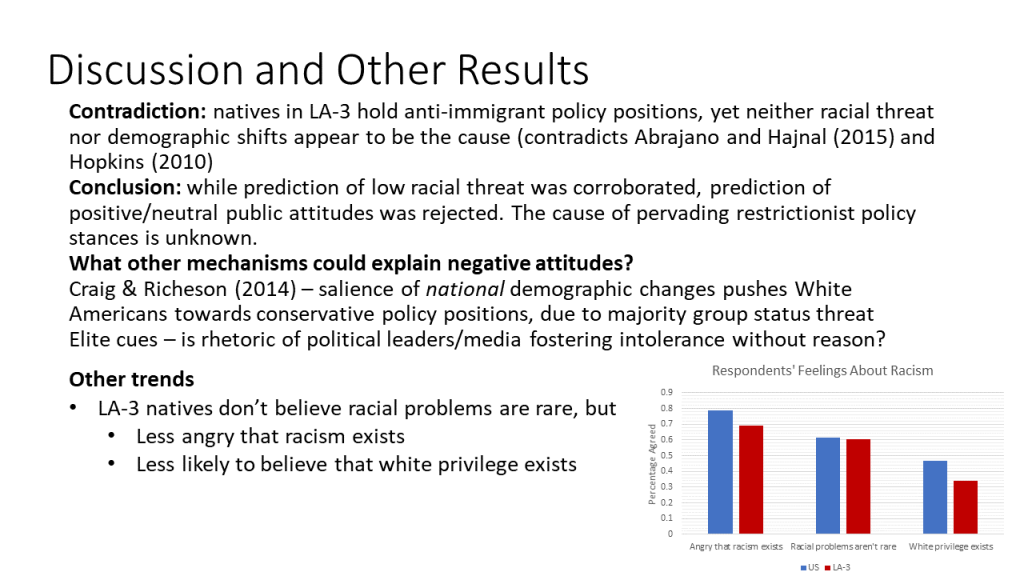

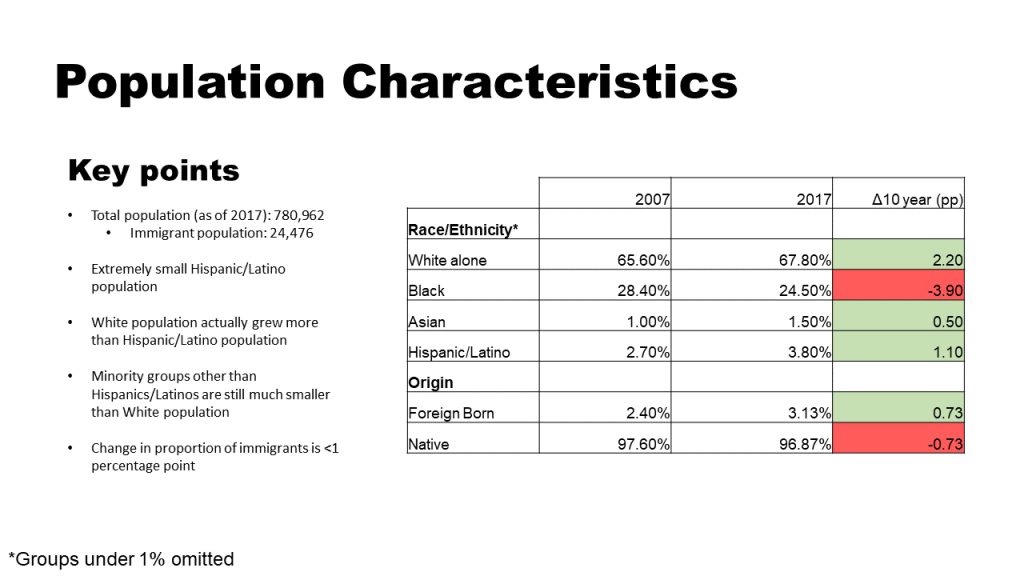

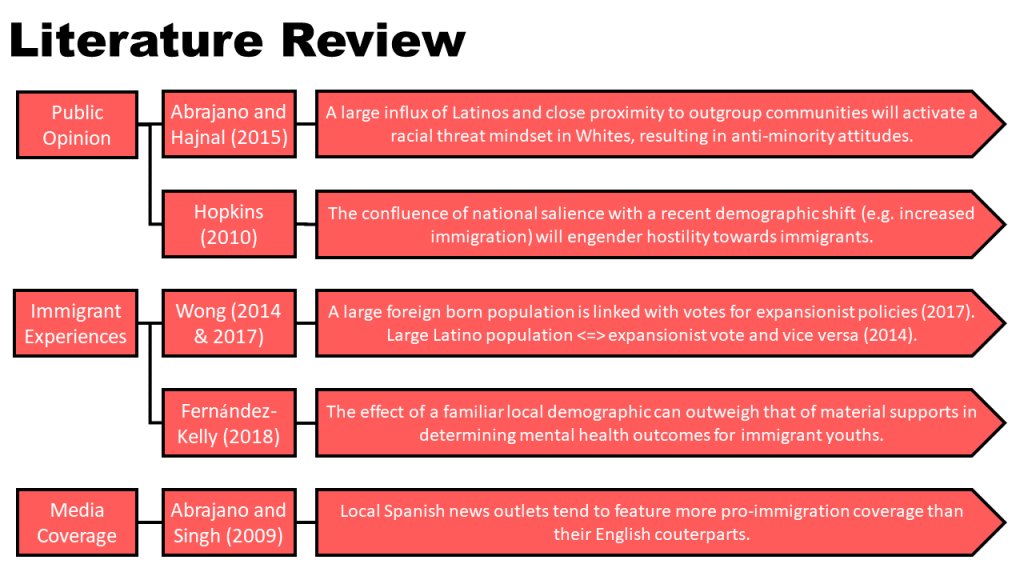

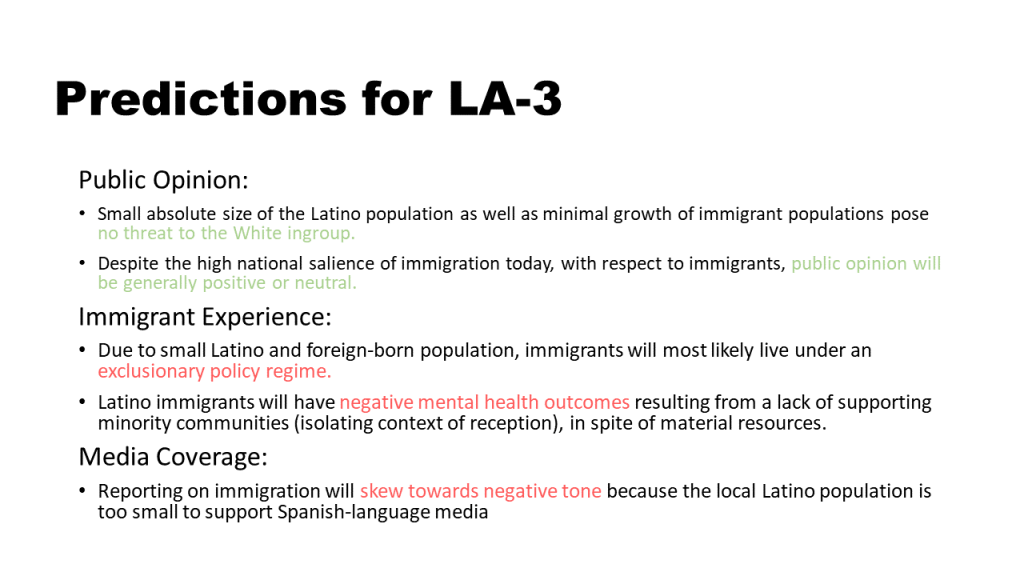

Most current literature on anti-immigrant attitudes in the US focuses on the effects of local immigrant population size or growth. However, according to the 2017 American Community Survey, the foreign-born population in LA-3 was only 3.13%, representing a 10-year change of only 0.73 percentage points. At least according to traditional models, residents of LA-3 have little reason to be afraid of or upset with immigrants or, as they are often conflated with, Latinos. However, my own research, using Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) data from 2016 has shown that a majority of White residents of LA-3 are opposed to legislation relating to amnesty or the DREAM Act, and supportive of deportation and increased border patrols. Notably, LA-3 natives are on average more anti-immigrant than the average American. The fact that these pervasive anti-immigrant stances exist, despite there being few immigrants nearby to trigger them, must then be explained otherwise. Some research indicates that elite cues, in the absence of local group contact, may be responsible.

It has long been recognized that the relationship between Americans and the media they consume is a two-way street. But at least in recent years, it seems as if the increasingly polarized media is at times deciding the population’s political views rather than informing them. For instance, one study found that for Latinos, consuming media from outlets less friendly towards immigration correlated with holding more anti-immigrant views. There is also reason to believe that media outlets in Louisiana specifically will tend to lean anti-immigrant, as another study found that news organizations closer to the US-Mexico border tend to report both more often and more negatively about immigrants. If we can extend these findings to residents of LA-3, it is not unreasonable to think that they may be swayed into anti-immigrant attitudes based more on the media than by any personal experience. Similarly, the rhetoric espoused by political leaders, such as President Trump and Congressman Higgins may have a noticeable effect on the salience of immigration for locals. A recent study found that Trump’s inflammatory remarks about immigration in June of 2015 (e.g. his comments about Mexican “rapists” and “criminals”) primed his voter base to mentally prioritize immigration. In LA-3 there is certainly no lack of vocal anti-immigration politicians who could trigger similar concerns. Between the media and political elite cues, it is not unreasonable that locals could develop anti-immigration attitudes without much personal foundation.

The fact that these viewpoints developed without personal contact may at first seem discouraging, but I believe there is a reason for optimism: views about immigrants may be malleable. One experiment showed that when study participants were asked to take the perspective of Syrian refugees, they were more likely to participate in supportive behaviors. Notably, this effect was observed in both Democrats and Republicans, indicating that this effect could cross party voting lines. In an experiment on intergroup contact, everyday encounters with Latinos over a course of weeks initially resulted in greater exclusionary attitudes, but gradually seemed to lead towards more inclusive beliefs. While the results of either study are not strongly conclusive, there is some reason to believe that learning about the plights of immigrants can foster sympathy and actual contact with immigrants over time can slowly engender more positive, inclusive feelings. While this does not address exactly how more information about immigrants can be distributed to locals in LA-3, it does seem to suggest that greater education and increased contact could help decrease current intolerance for immigrants.

Life for immigrants is certainly not easy anywhere, and Louisiana may be a particularly challenging state to settle in – due restrictionist policy regimes, the increasing presence of ICE as local detention facilities are filled with asylum-seekers, and of course the anti-immigrant rhetoric that Trump and other politicians may impart on locals. However, having a more welcoming local populace would go far towards improve immigrant outcomes and integration. Thus, I hope that you will consider, in addition to the critical work you do providing education and assistance to immigrants, the potential benefits of educating local residents. In increasing positive attitudes towards immigrants, it may be possible to not only create a larger network of supporters, but also to improve immigrant outcomes and build a more welcoming community.