Slide 1:

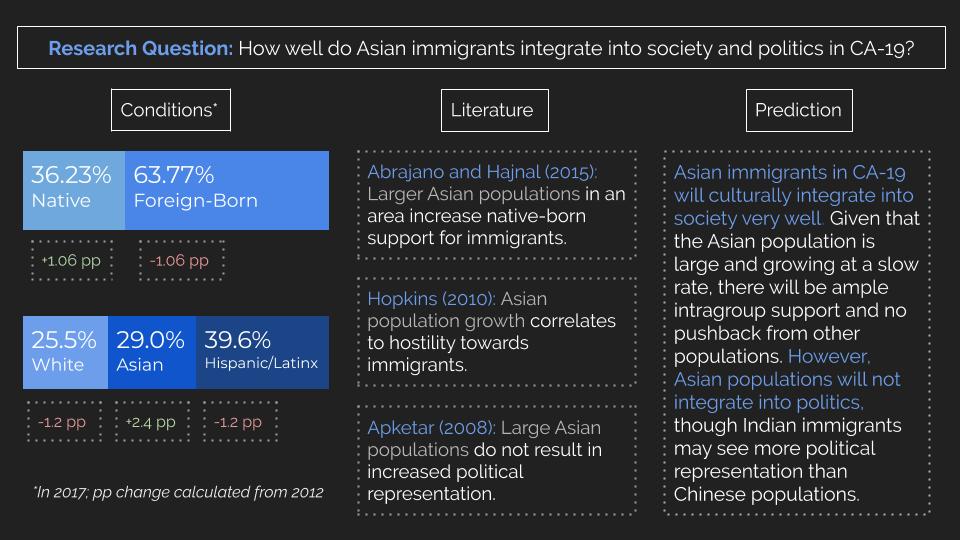

The existing demographic conditions of CA-19 make it an interesting place to study Asian immigration in particular. CA-19, or its corresponding geographical area, is almost evenly split between Asians (30%), Hispanics/Latinx (40%), and Whites (30%). Changes to this population from 2012 to 2017 have been small: since 2012, the Asian population has grown by 2.4 percentage points, while the Hispanic/Latinx population and White population has shrunk by 1.2 percentage points. Since 2012, meanwhile, the size of the foreign-born population has shrunk by one percentage point. In general, however, CA-19 is notable for its large foreign-born and Asian populations, shrinking White population, and overall consistency, with little demographic change. Meanwhile, there is much existing literature on Asian immigration and integration. Abrajano and Hajnal (2015) find that if an Asian population is significant, support for immigration from the native-born population increases. Rapid growth of an Asian population, however, may induce hostility against immigrants: Hopkins (2010) finds that when an Asian population expands quickly, attitudes towards the population also become more negative. Aptekar (2008) argues that though Asians are more readily integrated into society, even in places where they are prominent, they find difficulty being represented or integrating in politics. The literature suggests, therefore, that when an Asian population is large, Asian immigrants may integrate into society, but face difficulty achieving political integration. When an Asian population is rapidly expanding, however, neither cultural nor political integration is likely. Through qualitative interview collections, I plan to gauge Asian immigrant integration into politics and society in CA-19. I predict that, as the conditions and existing literature suggests, the large size of CA-19’s Asian population will allow Asian members of the community to be fully integrated into society. Though growth of an Asian population may play a role in increasing hostile attitudes regarding immigration, since CA-19 has seen very little change in its Asian populations in the last five years, hostility against immigrants may not manifest in CA-19. Despite their social and cultural integration, however, I predict that Asian immigrants of all nationalities in CA-19 will not be fully politically integrated or have their interests represented in politics. Aptekar (2008) does introduce the caveat that Asian Indians are more likely to be or have their interests represented in politics than Chinese immigrants; thus, I expect to find that Indians in San Jose may feel both culturally and politically integrated where other Asian immigrants only experience cultural integration.

Slide 2:

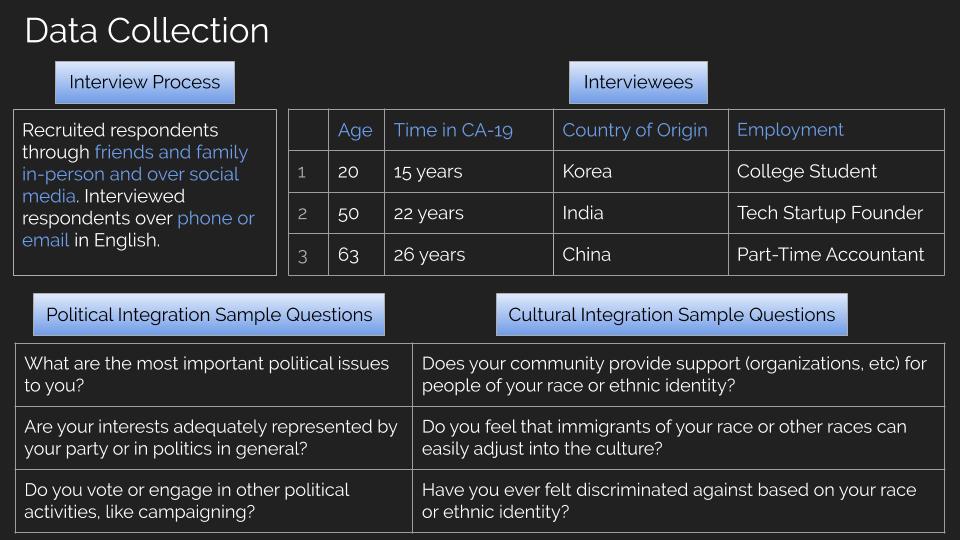

To test my prediction, I decided to interview first-generation Asian immigrants living in San Jose regarding their perceptions of their own political and cultural integration. I recruited interview subjects by asking friends and family in-person and through social media (a non-random process) and interviewed subjects over either phone or email, depending on the subject’s availability and comfort. Two interviewees opted for email so that they would have more time to answer the questions. In total, I interviewed three subjects, all of differing ages, backgrounds, and nationalities so as to provide more comprehensive data. Respondent 1 is a 20-year-old Korean male who is currently attending college in San Jose and has lived in the city for 15 years with his family. Respondent 2 is a 50-year-old Indian female who moved to San Jose 22 years ago to establish a high-tech startup with her husband. Respondent 3 is a 63-year-old Chinese female who has lived in San Jose for 26 years and currently works as a part-time accountant. Interview questions were split into three categories: Background, Political Integration, and Cultural Integration. Below is a full list of the questions asked.

Background:

- How old are you?

- What do you do for work/school?

- Are you a citizen?

- How long have you lived in your community?

- Why did you choose to live in your community?

Political Integration:

- Did you register to vote?

- Did you vote in your most recent state, presidential, and county-level elections?

- Are you affiliated with one of the two major political parties? If not, why?

- If you are party-affiliated, how well do you think the party you support represents your interests?

- Do you feel that your interests are represented in politics? How so?

- What are the most important political issues to you?

- Are you engaged in any political activities outside of voting (ie volunteering for campaigns, donating to candidates, fundraising or advertising, conversations with friends and family about politics)?

- How often do you talk about politics with friends and family? (Frequently, once in a while, not at all)

Cultural Integration:

- How would you define your community?

- How diverse is your community?

- How safe or comfortable do you feel in your community?

- Does your community provide support or organizations for you or people like you?

- Do you socialize with people from different races outside of work/school?

- Would you say you feel “American” (that you associate with your national identity) or do you think your ethnic identity is more salient for you?

- Do you feel that there is a specific Asian subculture in your community, or are Asians an equal part of a larger culture in your community?

- Do you feel that immigrants of other races can easily assimilate into your community?

- Have you ever been called racial slurs or by any derogatory names?

- Have you felt discriminated against on the basis of your race/ethnicity?

Slide 3:

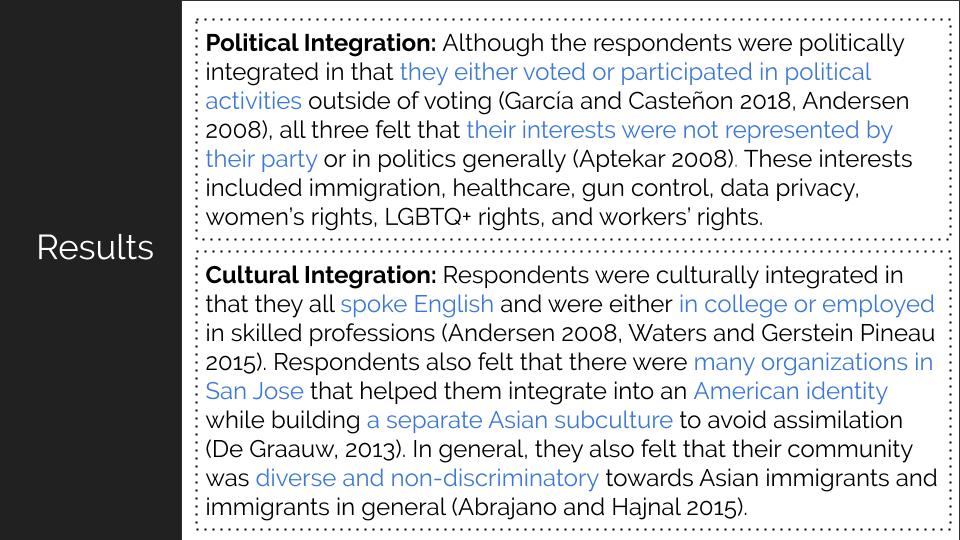

All three respondents were politically integrated in that they either voted or participated in political activities outside of voting. Respondents 2 (Democrat) and 3 (Independent) voted in all recent elections, while Respondent 1, as a DACA recipient, could not vote but participated in political activities (i.e. campaigning and fundraising for the Democratic Party). As García and Casteñon (2018) and Andersen (2008) explain, the act of voting or participating in politics can mark political integration into a society. In this regard, therefore, all three respondents were fairly politically integrated. All three respondents felt, however, that their interests were not represented by their party or in politics generally. Respondent 1 reported that he felt the Democratic Party to be fairly split on issues important to him, such as immigration, LGBTQ+ rights, and workers’ rights. Respondent 2, meanwhile, felt that the Democratic Party had no well-executed, comprehensive position on immigration, women’s rights, or data privacy, the issues most important to her. Respondent 3 felt that no political party was able to adequately represent her positions on healthcare reform and gun control, the issues most important to her. Aptekar (2008) writes that one measure of integration is interest articulation and representation; in this regard, therefore, the Asian immigrants interviewed were not politically integrated. In regards to the second portion of the prediction, respondents were culturally integrated in that they all spoke English and were either in college or employed in skilled professions. Some possible measures of cultural integration, as explained by Andersen (2008) and Waters and Gerstein Pineau (2015), is English language acquisition, educational attainment, and skilled, gainful employment, all of which all three respondents possessed. Respondents also felt that there were many organizations in San Jose that assisted in cultural integration while pushing back against total assimilation. Respondents 1 and 3 mentioned Korean and Chinese schools in the area that helped to teach young children the language and culture of their respective countries; these schools operated only on the weekends so that they would not conflict with “regular” school, thereby impeding language acquisition or educational attainment. Respondent 2, meanwhile, mentioned Indian community centers that hosted networking events and job fairs to promote employment in the area while also hosting Bollywood stars, classical music classes, and Holi festivals to encourage cultural preservation. De Graauw (2013) explains that immigrant advocacy and cultural organizations are often highly important in integrating immigrants into their host community while helping to preserve their culture, and all three Asian immigrants interviewed felt that these organizations had been helpful in that regard. They felt very much a part of the San Jose community and consciously identified themselves as “American” through their education, employment, and values systems, but were also very aware of their ethnic identity and felt as if they were part of an Asian subculture within the larger body. A final indicator of cultural integration was that all respondents felt that San Jose was very diverse, with high levels of socialization between people of different races, and was non-discriminatory towards immigrants in general. Given that all respondents felt welcomed and not targeted for their Asian immigrant status or racial identity, there seems to have been minimal native-population backlash against Asian immigrant populations and a welcoming attitude towards cultural integration, as Abrajano and Hajnal (2015) predicted.

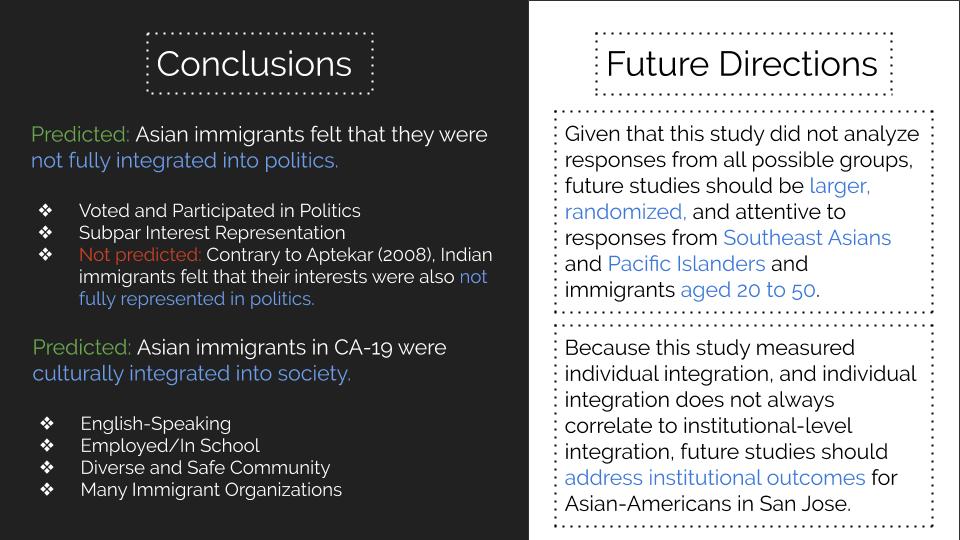

Slide 4:

The results found through the three interviews generally supported the initial predictions. Political integration of the interviewed Asian immigrants was limited, given that all three respondents voted or participated in politics on a regular basis but still felt as though their interests were not well-represented in politics. Culturally, however, all three respondents were well-integrated, given their educational attainment, language acquisition, employment status, acknowledgement of the various cultural organizations that had supported them in balancing their Asian and American identities, and personal feelings of diversity and inclusion within the city. In general, the predictions were all well-supported by the results. There was one caveat, which was that Indian immigrants, like the East Asian immigrants interviewed, also felt as if their political views and interests were not represented. This was directly contrary to Aptekar’s (2008) findings, which were that in Edison, New Jersey, Indians were more likely to be politically integrated than Chinese immigrants. Given that Aptekar (2008) occurred in one small geographical location far from San Jose, however, it is entirely possible that her results were simply not generalizable to other regions. This study, of course, had a fair number of limitations. Because the study utilized non-random sampling and a small sample size, in future studies, randomization of interview collection as well as a larger body of responses would be helpful. Further, though my results encompassed Asian immigrants of differing nationalities and age groups, I was not able to interview Southeast Asians or Pacific Islanders, nor was I able to interview Asian immigrants between the ages of 20 and 50. In future studies, targeting those groups for interviews would lead to more comprehensive, representative results. Finally, the nature of this study made it so that the focus of the study was on individual-level integration, rather than on institutional-level, group outcomes. Given the differences between individual-level integration and group integration, and that individuals can be more or less integrated where larger groups are not, there is ample opportunity for work to be done analyzing institutional-level integration, cultural and political, for Asian immigrants in San Jose.