Title Slide: The images in this title slide are meant to introduce the viewer to the district’s demographics. One image is of protestors holding signs written in Spanish, the next is of White and Asian “techies” at a conference, and the third is of Asian runners participating in a race.

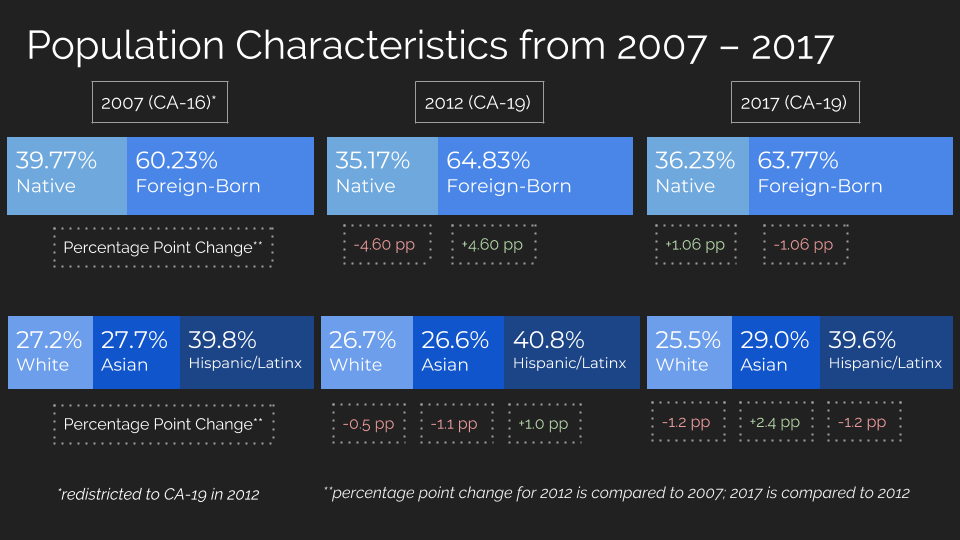

Slide 1: From 2007 to 2017, CA-19, or its corresponding geographical area, has remained almost evenly split between Asians (30%), Hispanics/Latinx (40%), and Whites (30%). Changes to this population have been small: the Asian population shrunk by one percentage point post-redistricting and grew by two percentage points five years after that. The Hispanic/Latinx population, meanwhile, grew and then shrunk again by one percentage point in the span of a decade. The only notable trend is that Whites have shrunk by 1.5 percentage points over the course of the decade, which, though consistent, is still very small. Before redistricting occurred in 2012, CA-19, or what was then CA-16, was around 60% foreign-born and 40% native-born. Post redistricting, the foreign-born population grew by 4.6 percentage points, but shrunk again by one percentage point. In general, however, CA-19 is notable for its large foreign-born, Latinx, and Asian populations, shrinking White population, and overall consistency, with little demographic change in the last ten years.

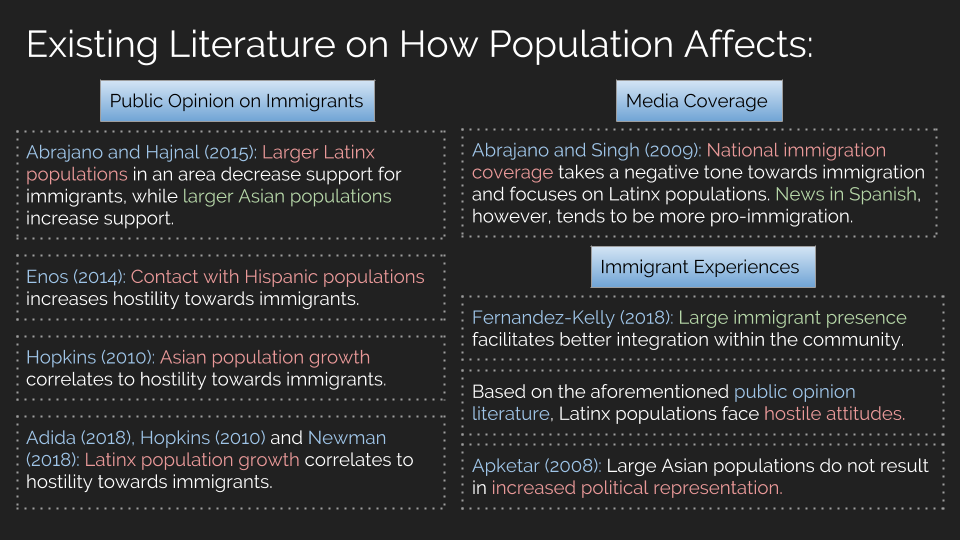

Slide 2: In terms of existing literature, it is clear that the size and growth of various immigrant populations impact public opinion, local media coverage, and their own lived experience in different ways. In terms of public opinion, Abrajano and Hajnal (2015) find that once the Latinx population reaches a certain size, support for immigration decreases; if an Asian population is significant, however, support for immigration increases. Enos (2014) builds upon that literature by suggesting that short-term contact with Hispanic populations increases hostility towards immigrants in general. Other literature focuses not on size of the immigration population, but on growth, which Abrajano and Hajnal (2015) suggest is weakly related to attitudes towards immigration. Hopkins (2010), Newman (2018) and Adida et al. (2018) all find that the rapid growth of Latinx populations increases hostility towards immigrants. Hopkins’ “politicized places” theory, for instance, argues that when communities are undergoing large growth in Latinx populations at the same time that salient national rhetoric politicizes immigration, hostility towards immigrants will increase (Hopkins, 2010). Adida et al. (2018), meanwhile, argues that large growth in Latinx populations results in increased support for restrictionist immigration policies; Newman (2018) argues that when communities undergo the lived experience of Latinx population growth, their attitudes towards Latinx immigrants interact with Trump’s rhetoric and become more hostile and adversarial. Rapid growth of an Asian population, meanwhile, may also induce hostility against immigrants: Hopkins (2010) finds that when an Asian population expands quickly, attitudes towards the population also become more negative. When taken together, the literature seems to suggest that largeness of, close contact with, and fast growth of a Latinx population increases general hostility towards immigrants. A large Asian population decreases hostility towards immigrants, but if the Asian population grows very quickly, that effect quickly mimics the trajectory of the Latinx experience. In terms of media coverage, Abrajano and Singh (2009) suggest that national news coverage of immigration tends to focus on Latinx immigration, using a very negative tone. When compared to news published in English, however, Spanish news are seen to be more positive about immigration as a whole and use more positive language. Therefore, an area with large quantities of news published in Spanish may see more positive media coverage of immigration as compared to the national average. Finally, in terms of the overall immigrant experience, the literature varies. The literature previously discussed in terms of public opinion applies here: Latinx populations, large or growing in size, face hostile attitudes towards them and towards immigrants in general from the communities that they join. Professor Fernandez-Kelly (2018), however, argues that large immigrant communities can help facilitate integration, by providing immigrants with a support system for societal integration. This applies, in particular, to Hispanic/Latinx populations in various parts of New Jersey. In terms of the Asian population, Aptekar (2008) argues that though Asians are more readily integrated into society, even in places where they are prominent, they find difficulty being represented or integrating in politics. The literature suggests, therefore, that Latinx populations may or may not have a difficult time integrating into society and politics, depending on their reception by the native population and by their immigrant peers. Asian immigrants may integrate into society, but face difficulty achieving political integration.

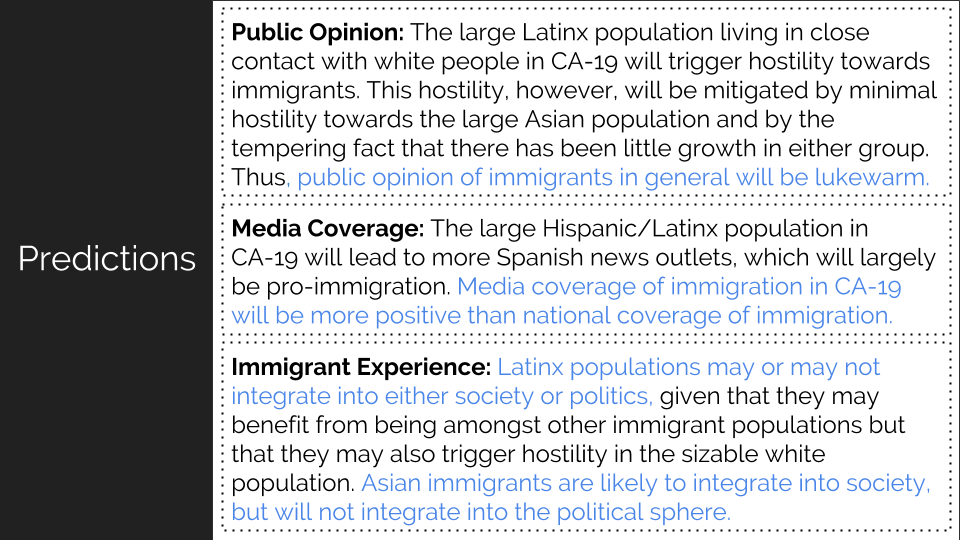

Slide 3: This literature can allow us to make predictions about CA-19. First, in terms of public opinion, the largeness of the Hispanic/Latinx population and the close contact that White residents will have with them indicates that there will be hostility towards immigrants as a whole. The largeness of the Asian population, however, as a non-threat to White populations, may mitigate that general ill-will. Meanwhile, as described before, CA-19 has seen very little change in either its Latinx or its Asian populations in the last decade; therefore, though growth of both Latinx and Asian populations may play a role in increasing hostile attitudes regarding immigration, the effects may not manifest in CA-19. The overall prediction, therefore, is that based on size of population alone, public opinion of immigration will be lukewarm: cold towards the size and proximity of Latinx populations, but warm towards the size of Asian populations. Second, in terms of media coverage, 40% of CA-19 is either Spanish-speaking or Latinx. CA-19 is likely to have numerous Spanish-speaking news outlets, and as Spanish new outlets tend to be more positive towards immigration than a national news outlet, CA-19 is likely to see more positive local media coverage of immigration, especially as compared to national media coverage. Third, in terms of the overall immigrant experience, CA-19 is, while very largely Latinx and Asian, also fairly White. Latinx immigrants thus may find it easy to integrate thanks to robust immigrant communities (40%), or may face backlash and hostility from the White native population. Asian immigrants, meanwhile, may find it easy to integrate into CA-19, given the robust size of the Asian population (30%), but still may not be adequately represented in or allowed to participate in politics, be it at the local, state, or federal level.

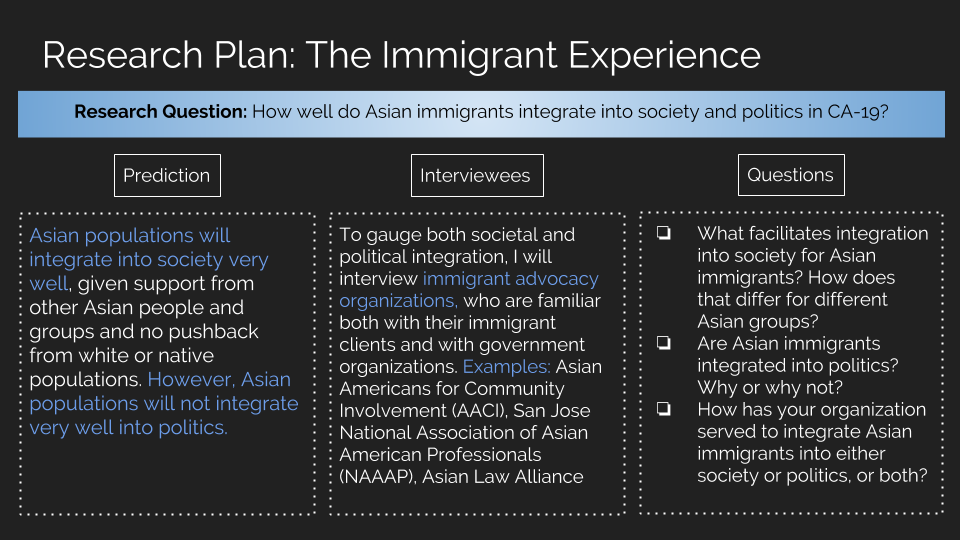

Slide 4: I plan to gauge Asian immigrant integration into politics and society through qualitative interview data collection. As already mentioned, I predict that the large size of CA-19’s Asian population will allow Asian members of the community to be fully integrated into society, be it through educational attainment, employment status, or income attainment, to name just a few measures of integration. Despite their social integration, however, I predict that Asians in CA-19 will not be fully politically integrated or represented on multiple levels of government. In order to look at both societal and political integration, I plan to interview a number of immigrant advocacy groups, which will give me insight into both. Immigrant advocacy groups, as argued by authors like DeGraauw (2013), work alongside both the immigrants that serve as their clients and government officials that want to use the knowledge that advocacy groups possess to better serve immigrants’ interests. These groups will therefore be one of the most reliable sources to draw upon in understanding the integration of immigrants into societal and political life in CA-19. Some groups that I would get in contact with for interviews include Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI), San Jose National Association of Asian American Professionals (NAAAP), or the Asian Law Alliance. Preliminary general questions for these organizations include “What facilitates integration into society for Asian immigrants? How does that differ for different Asian groups?” or “Are Asian immigrants integrated into politics? Why or why not?” I would also want to differentiate between different service providers by asking specific questions like “How has your organization served to integrate Asian immigrants into either society or politics, or both?” Upon completing my qualitative interviews with immigrant advocacy groups, I would compile the data and gauge the accuracy of my predictions in a written report.