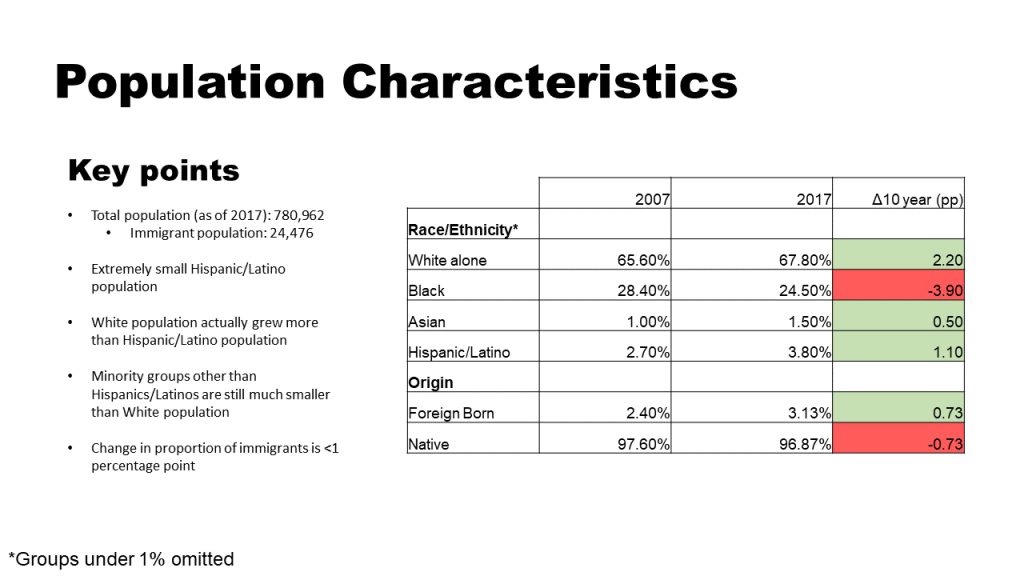

While much of the literature in class thus far has focused on areas where there are large or rapidly growing immigrant populations, LA-3 has remained stagnant, at least in the past 10 years. Across all ethnic categories, the largest change between 2007 and 2017 was ~4 percentage points (decrease in Black population). Our populations of interest experienced even less change, with the Latino population growing only 1.1 percentage points. As a point of comparison, the White population actually grew twice as many percentage points, so it is safe to assume that LA-3 is not a district where minorities are threatening the existing ingroup, at least not by force of numbers. This is particularly true when we examine the size of the Latino population, which is just 3.8% of the district as of 2017. The numbers for immigrants are similarly small and constant, composing just 3.13% of the population, and growing 0.73 percentage points. Thus, in context of immigration, the most salient characteristics of LA-3 are that populations of interest (Latinos and immigrants) are small and relatively unchanging.

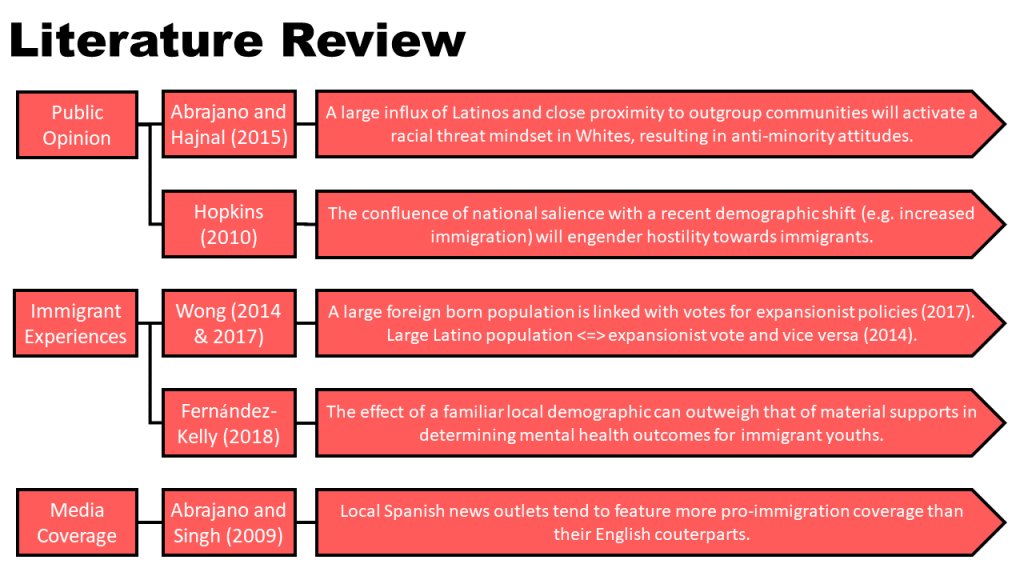

With respect to public opinion, most research on immigrants has centered on how demographics lead to hostility or backlash against outgroups. For instance, in White Backlash, Abrajano and Hajnal describe a theory of racial threat, where a large outgroup begins to take the resources (political, material, etc.) of the ingroup, thus sparking retaliation (2015). Notably, the ingroup must be aware of the outgroup, which requires some proximity/contact between the groups. The American public tends to conflate Latinos with immigrants in general, so this racial threat mindset against Latinos would effectively result in the same treatment of immigrants in general, at least according to the authors. Hopkins actually disagrees with the application of racial threat to immigrants, and instead explains hostile attitudes towards immigrants as the result of intersecting national salience and demographic shifts (2010). For instance, immediately after 9/11, fear of immigrants was at an extreme high; any observed growth in immigrant populations at this time would result in retaliation against immigrants. For the purposes of this analysis, its worth noting that national salience has probably been high since the beginnings of the Trump campaign, and thus analysis of present-day attitudes surrounding immigration probably will depend primarily on demographic shifts. Under this assumption, Abrajano and Hajnal and Hopkins lead to the same conclusion: large and/or fast-growing Latino/immigrant populations will be met with backlash. While this backlash is almost certainly linked to the experiences of immigrants, I choose to focus on two more measurable areas of study. In multiple papers, Wong examines the effect of constituency composition on voting patterns in Congress. One paper examines the effect of Latino population size on Congressional votes for a policy of interior enforcement (287(g) of the IRIRA), finding that Latino population size negatively correlates with votes for greater enforcement (2014). Another paper finds that having a large foreign-born population correlates with votes for expansionist policies, so this correlation seems to work in both directions (2017). On a more micro-level, Fernandez-Kelly’s study of immigrant youths in New Jersey and their ability to cope with adverse conditions examines some of the factors that determine whether immigrants can integrate successfully into new environments (2018). One factor that Fernandez-Kelly emphasizes is the importance of the local context of reception, and in particular the presence of an existing community. While this can take many forms (e.g. joining either an existing Latino community or merging with the local Black community), the point remains that context of reception can affect outcome regardless of what material resources may or may not be present. Finally, in the realm of media coverage, Abrajano and Singh examine the skews observable in Spanish and English-language media, on the topic of immigration (2009). The authors find that, somewhat unsurprisingly, Spanish-language media is more sympathetic to pro-immigration causes and legislation. Thus, with the combination of these factors, we can begin to predict how the immigration landscape in LA-3 might look.

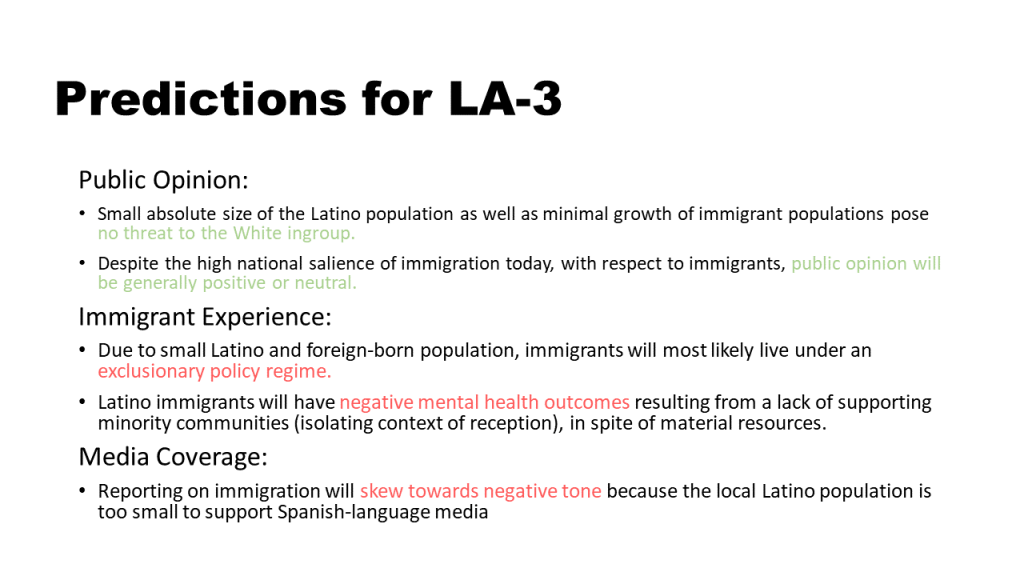

Application of literature on public reception to LA-3 is somewhat complicated by the fact that the literature focuses on locales with either large Latino or immigrant populations or rapidly growing ones. However, LA-3 is neither of these. Instead, we can try to make inferences by applying the inverses of these authors’ conclusions. For instance, Abrajano and Hajnal and Hopkins see either large or fast-growing populations as a predictor of backlash. Since LA-3 features neither of these, we can instead predict that there will be minimal hostility towards immigrants, as they pose no threat to the ingroup. Making predictions about the immigrant experience is somewhat easier: based on Wong’s findings, we can easily predict that the small foreign born and Latino populations of LA-3 will enable representatives to vote for restrictionist policies. Similarly, the tiny Latino/immigrant population and relatively small Black and Asian populations offer little opportunity for solidarity, predicting poor mental health among Latino immigrants. Media coverage requires one further step: first we assume (admittedly without evidence) that the small Latino population would be inadequate to support a Spanish-language media outlet in LA-3. If we take this to be true, then we would predict news coverage to generally be negative towards immigration, as per Abrajano and Singh, as only English-language sources would exist.

Researching any aspect of immigration in LA-3 is a challenge, as the small population of immigrants doesn’t seem to attract much attention. With this limitation in mind, I chose to further examine my prediction about mental health in immigrants, as a relatively small number of interviews would suffice for a qualitative description. While there are not many immigrant advocacy groups, I was able to find two within LA-3. I plan to contact these organizations to find interviewees. Even if these organizations are unable to provide interviewees directly, I am hoping that they can provide a snowball sample of sorts, as both organizations offer referrals to other organizations for immigrants; if I can track down other organizations that serve immigrants, my odds of finding enough interviewees should be adequate. While I would love to additionally research what material supports are available to immigrants, research thus far has been unfruitful. Instead, I will try to get as much information about the local context from the interviewees. The questions I ask will aim to examine many of the same areas as Fernandez-Kelly’s study, including outcomes (such as educational attainment, or categorization as achievers, stayers, insurgents, and skidders), outlook, sense of belonging (to their own culture, as well as their geographic locale), and public reception. Once I have collected enough interviews, I will try to code responses in these main categories to establish the general orientation of outlook, outcome, community, and public reception and report on any surprising or expected features.