The Wicked Witches of the Left:

Feminist Power and the “Sexy Witches” of the 1970s

Katie Duggan

SYNOPSIS

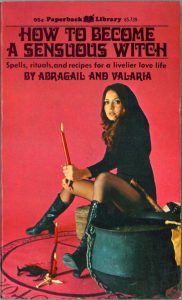

There are a million different variations and sub-tropes of the witch, calling to mind everything from pointy hats, black cats, and broomsticks to old hags with warts and gray hair to enchanting women using their alluring powers for love. Not only are witches popular figures in Halloween costumes and films, they are also prominent presences in the feminist political sphere. From Wiccans and neopagans to the radical feminist group W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Group from Hell), the name “witch” has been used to symbolize feminine power and rebellion against patriarchy. My project looks at real-life political and cinematic witches in the 1970s, mostly in the United States, and the diversity (or lack thereof) in conceptions of what being a witch mean. I call this trope the “sexy witch” due to the numerous sexploitation films and genre B-movies from the decade that depicted witches as attractive, sexualized, sexually adventures young women. The films I focus on from the decade are Mark of the Witch, Psyched by the 4D Witch (A Tale of Demonology), Season of the Witch, and Virgin Witch. All four of these films feature white, conventionally attractive women becoming witches. All of these narratives connect the attainment of sexual power with becoming more overtly sexualized and sexually active.

But while the witches in these films shared many similarities, actual witches did not always share the same definition of their identity; some saw it as a religious identity, some as a political one, some as an individual thing versus a community-based one. The identity crisis of what a “witch” looks like has historically been mobilized by groups of women who use it to unite diverse groups of women (like W.I.T.C.H.) and push for greater rights. In Drawing Down the Moon, a 1979 sociological study of pagans in the United States, American journalist and Wiccan Margot Adler explores the many different ideas of what a witch is, and writes that the very power of the witch identity lies in the name’s imprecision. According to her interviews with self-identified witches, many feminists and practicing witches consider the witch as a being conceived in rebellion, an unstable category capable of transfiguration, a “changer of definitions and relationships.” In my paper, I analyze the connections of witchcraft to feminism and female networks of power, as well as the representations of fear of the sexuality of women, particularly women of color. Ultimately, I conceive of the witch as a figure in the center of fights for power between women and patriarchal forces of oppression, constantly shifting in response to the pressing issues of the time.

MEDIA LINKS

Main texts – 1970s witch films

- Mark of the Witch (1970) trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F2ggWthfSro

- Virgin Witch (1971) trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyixXFzmJv8

- Season of the Witch (1972-1973) trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3FT6xndS1Y

- Psyched by the 4D Witch (1973) trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbbaB2foJsw

Additional resources from self-identified witches

- Laurie Cabot, “The Official Witch of Salem” in the 1970s, provides a guide for cooking at a pagan Samhain feast https://munchies.vice.com/en_us/article/z4gqej/we-asked-salems-official-witch-what-to-eat-at-a-pagan-sabbat

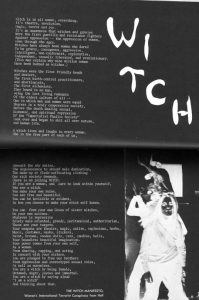

- Manifesto of W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell) // their current website https://www.witchboston.org/about/

- Guide to starting new chapters of W.I.T.C.H.: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58bc4014db29d66bb3b20966/t/59c6e45fd7bdce9acafab603/1506206816220/NEW-W.I.T.C.H.-CHAPTERS.pdf

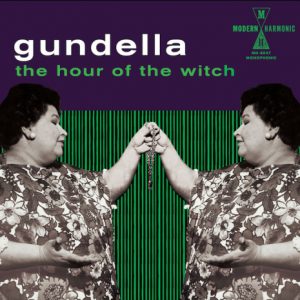

- Gundella: The Hour of the Witch (1971): Interview with self-identified “green witch” Gundella, who refers to her background as descending from a family of witches in Scotland. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vluocaw8vAM She also released an LP of spells, some of which can be heard here. Her first words on the LP are “Yes, I am a witch.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sIUaTNLikIY

FINAL PAPER LINK

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans In America Today. New York: Viking Press, 1979.

Adler, a Neopagan herself, documents a history of the United States Neopagan movement from a sociological perspective. She attended ritual gatherings and interviewed self-identified witches across the United States as well as in Britain about their diverse cultural backgrounds and spiritual beliefs united under the term “witch.” This text is seen as a departure from other accounts that often equated witchcraft with Satanism, and was credited with popularizing interest in and scholarly attention to earth-based religions.

Berger, Helen A. “Witchcraft and Neopaganism.” In Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America, edited by Helen A. Berger. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

I analyzed selections from this book by Helen A. Berger and Wendy Griffin on Witchcraft and Neopaganism and Feminist Spiritualities, respectively. This book traces the New Age and Neopagan religious movements, and examines more radical feminist groups drawing upon spiritual sources, including feminist action group W.I.T.C.H (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell). This source argues for the irrevocable link between second-wave feminism and the symbol of the witch—witches symbolize opposition to patriarchal forces, and allow for the assertion that the personal is spiritual.

Grant, Barry Keith. “Taking Back the Night of the Living Dead: George Romero, Feminism, and the Horror Film.” In Zombie Theory: A Reader edited by Sara Juliet Lauro, 212-22. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Quotes Season of the Witch director George Romero as envisioning his film as a feminist one, as the protagonist Joan feels trapped by her domestic life and abusive husband.

Kelly, Casey Ryan. “Sexploitation in Abstinence Satires.” Abstinence Cinema: Virginity and the Rhetoric of Sexual Purity in Contemporary Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016, pp. 108–127. JSTOR.

This piece, on contemporary “abstinence satire” comedies, questions the resurgence in virgin characters and discussions of virginity in teen sex comedies. Casey Ryan Kelly writes of the abstinence satire” genre that these kinds of films exploit both sex and abstinence within the same text, and I use this as a framework for examining Virgin Witch and other sexploitation films of the period that simultaneously depict anxieties over female sexuality and desires to see it onscreen.

Langone, Alix. “Brooklyn Witches Plan to Put a Hex on Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.” TIME, October 14, 2018.

This piece from October is a news article covering a group of witches from Catland books, an occult bookstore in Brooklyn, who gathered to put a hex on Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh after he was confirmed despite facing allegations of sexual assault. This news example is illustrative of the frequent reappearances of the “witch,” particularly in response to moments of feminist crisis.

Lara, Irene. “Bruja Positionalities: Toward a Chicana/Latina Spiritual Activism.” Chicana/Latina Studies 4, no. 2, 2005.

Lara explores the construction of the identity of “la Bruja”—a witch, or a female practitioner of spiritual, sexual, and healing knowledges—in the literature and popular culture of the Americas. She argues that the oppression of the bruja was often in response to fears over her power and knowledge, especially as her power often operated outside patriarchal networks.

Layne, Jodie. “How To Use Tarot In Your Self-Care Routine.” BUST Magazine. Accessed January 06, 2019.

One example of contemporary interest in tarot as a self-care ritual, particularly in queer communities.

Lorde, Audre. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007.

Lorde writes that women have been historically made to distrust their knowledge, and the power within themselves; the possibility of a power within relates clearly to the idea that any woman can be a witch. Lorde’s work connects the spiritual dimensions of the witch identity and its political uses, as she argues that the “dichotomy between the spiritual and the political is also false, resulting from an incomplete attention to our erotic knowledge.” I use this to understand the erotic power of the 1970s sexy witch, and the function of her sexuality and sexualization. Through this lens, the eroticism of the witch is her power, and she represents women accessing their erotic knowledge.

Mark of the Witch. Directed by Tom Moore. By Mary Davis and Martha Peters. United States: Lone Star Productions, 1970.

This American film is from a screenplay by two female co-writers, and is an example of the many cheaply made witch genre films of the 1970s. A female college student unwillingly summons and becomes possessed by a 300-year-old witch. Her transformation in personality after becoming possessed, manifesting in a more outwardly expressed sexuality, is representative of the close relationship between witchcraft and discovering or acting upon sexual desires.

Moseley, Rachel. “Glamorous Witchcraft: Gender and Magic in Teen Film and Television.” Screen43, no. 4 (2002): 403-22.

Moseley examines makeovers, beauty transformations, and witchcraft in teen films and works like Bewitched, with a focus on the concept of “glamour.” She studies the relationship between feminism and femininity, arguing that magical femininity was often tied up in conceptions of charm, physical beauty, and glamourous allure. In addition, moments of physical transformation for these young women were often prompted by the attainment of adult sexuality or reaching puberty.

Psyched by the 4D Witch (A Tale of Demonology). Directed by Victor Luminera. United States: New Art Films, 1973.

Psyched by the 4D Witch features no synchronous sound, and the picture is overlaid with voiceovers of the young, virginal Cindy relating the story of her encounters with an ancient witch, Abigail, all accompanied by psychedelic music. Abigail teaches Cindy the rituals of sexual witchcraft, which supposedly will enable her to enact her sexual fantasies on the astral plane while remaining a virgin.

Season of the Witch. Directed by George A. Romero. United States: Jack H. Harris Enterprises, Inc., 1972-1973.

This work by famed zombie filmmaker George A. Romero is perhaps the most explicitly feminist of the 70s witch films studied in this analysis (Romero defined his goals in making the film as depicting feminist issues). It centers on a suburban housewife trapped in an abusive marriage, who becomes involved in witchcraft. The look and marketing of the film made it out to be similar to a softcore pornographic film, although little actual nudity is depicted.

Virgin Witch. Directed by Ray Austin. United Kingdom: Tigon Film Distributors Ltd., 1971.

A British horror exploitation film about an aspiring model, Christine, and her sister Betty, who are lured into joining a coven. Sybil, the coven’s high priestess, is depicted as having a predatory sexual interest in Christine, and tries to have the virginal Betty initiated into the coven. All the women involved are frequently placed in sexualized situations and nude scenes, with the initiation into the coven involving a sex ritual with a male authority figure.

Wagner, Marsden. “Hunting Witches: Midwifery in America.” Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006, pp. 99–125. JSTOR.

This article explores the history of midwifery and female communities of reproductive knowledge, and the midwife’s historical place as center of the woman’s world. It examines the efforts of the healthcare industry and government authorities to restrict who could practice medicine and reduce the role of the midwife, as well as the history of midwives being tried in court for witchcraft. Wagner argues that midwives, like witches, threatened patriarchal systems of power and knowledge and thus had to be controlled.

Zuras, Matthew. “We Asked Salem’s Official Witch What to Eat at a Pagan Sabbat.” Munchies, VICE. October 31, 2015. Accessed January 06, 2019.

Interview with Laurie Cabot, a witch who was given the title of “Salem’s Official Witch” by former Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis in the 1970s. Cabot gives advice on recipes for Samhain, the Celtic harvest festival, and tells her favorite recipes and herbs and plants to use.