I was really moved by watching Video Remains and the many different pieces on AIDS activism we’re been watching in the past few weeks. I am especially interested in exploring the relationship between images and memories further— how do we create memories in and through film? While home for Thanksgiving, I spent a lot of time with my family looking at old photo albums, which made me remember just how strange it is to see the younger selves of the people who you were familiar with only in their old age—or see photos of yourself when you were younger. One aspect of the footage from United in Anger that I found striking was the juxtaposition of the footage of interview subjects with footage of their younger selves at ACT UP protests. Perhaps even more noticeable were the people who didn’t have such doubling onscreen—who were only seen in the archival footage, because they died of AIDS in the following years. Photographs and films are not just signs of physical presence, but evidence of absences. The negative space, the gaps in our footage and in our collective memory, become just as important to be aware of as what is there. The footage, while it notes absence, can also suggest a wholeness or totality that has since been lost; as Alexandra Juhasz says of her videos, “the footage remains so alive, while the people remain so dead.”

So what are viewers today supposed to do with this “alive” footage, even as they remain incomplete? As Juhasz asks us in Video Remains and its accompanying text, “How do you remember? Have you remembered enough?” What do we do with our memories? What do we do when our memories of people aren’t strong enough, or are absent altogether? In some of the other works we’ve seen in the past few weeks, memory and footage are juxtaposed with one another, supporting one another while serving as different depictions of the past. Oral history was important to AIDS activism and its subsequent documentation, and United in Anger notably lacks voiceover narration and allows the interview subjects to talk about their experiences in their own voices. In this documentary, we are allowed to bear witness to archival footage alongside the memories of these people. The footage itself might seem like a “true” or “realistic” depiction of events, but it is also incomplete as a memory— and is supplemented by the personal perspectives we see through interviews with people like Gregg Bordowitz. Juhasz’s Video Remains and footage of her close friend James still feels incomplete without some knowledge of her own story, and has acquired a new significance to me after meeting her in person and getting to hear her talk about her work and the importance of that video firsthand. Memory is an intensely personal and intimate thing, and though videos may be able to capture and transmit shared memories and shared histories, there is still an individual element to it, as the videos can conjure up these memories that only you can truly know.

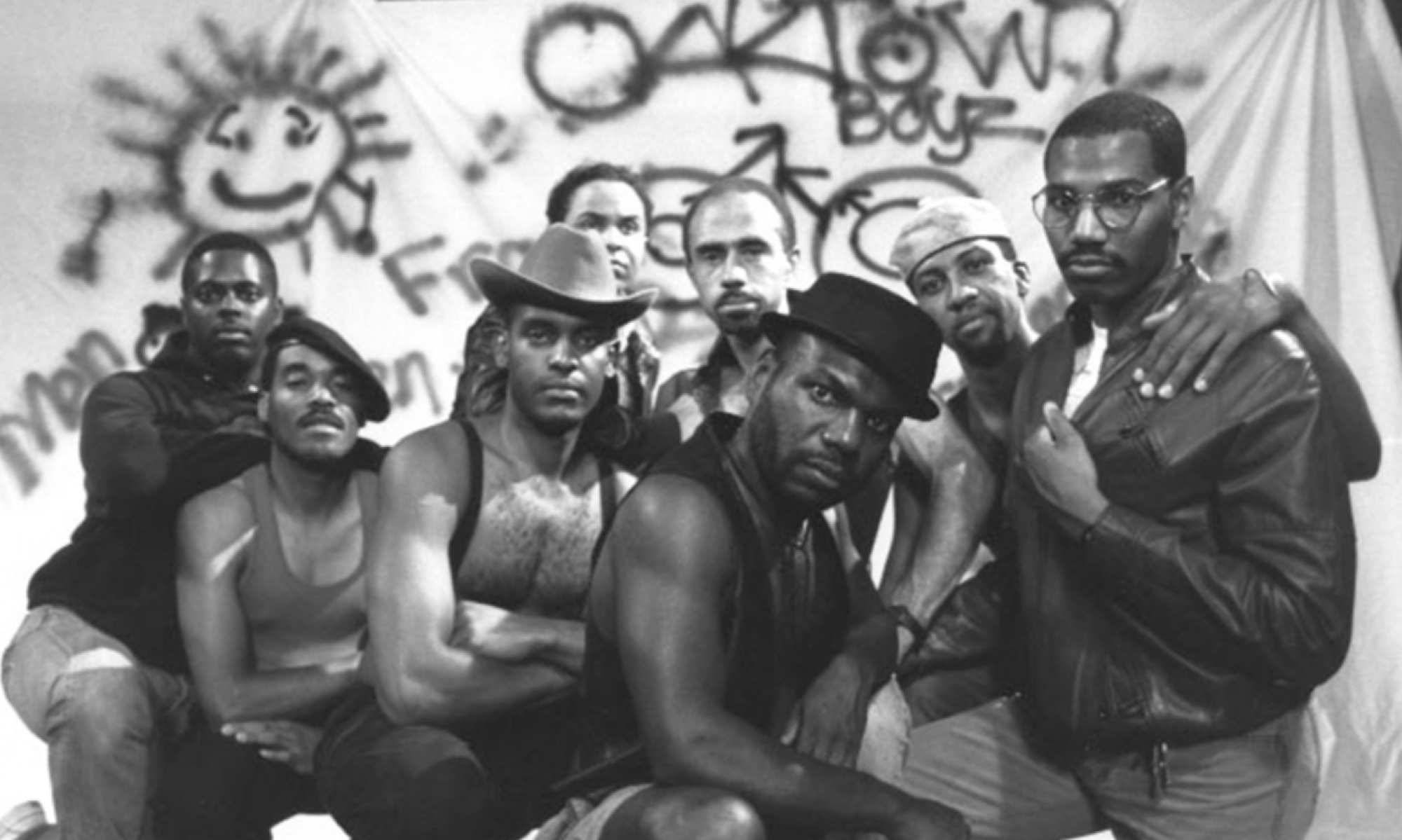

In the case of United in Anger, the viewers were fortunate enough to hear the firsthand experiences of ACT UP activists; we were able to hear Juhasz talk about Video Remains. But in the absence of these personal perspectives, whose responsibility is it to pass down the missing details and oral histories that accompany the footage? When watching home movies or flipping through family photo albums, my parents can fill me in on some of the contextual information—which great aunt that is in the background, whose house this Christmas party is at. But without them passing down that knowledge, it will soon be lost forever. Once more years pass and we get further removed from the memory—most people my age today have never known anyone with AIDS—how can we still remember? These questions are at the core of all the works we’ve been discussing in the past few weeks—from The Watermelon Woman and the invented archives, to Tongues Untied articulating the need for visibility. The creation of these films serves as an act of memory-making for the filmmaker, but the activist impulses of all of them argue that these memories are not just for personal use– they are to motivate viewers to remember and act. Years from now, perhaps the videos and images and texts will be all that’s left, removed from their initial memories, and future generations will have to do their best to remember what is there, and remember all that might have been lost. Perhaps a memory of memories is all a filmmaker or documentarian can strive for… and even prompting the viewer to try to remember as best they can, or create a pseudo-memory out of incomplete fragments, allows the knowledge—of AIDS, of lives lost, of families and friends—to be carried forward.