The Evolution of the Smart, “Nerdy” Female Movie Character

While thinking about different character archetypes to explore in this final project, I looked back at the films we viewed during the course. One character that especially interested me was Kay Scott All That Heaven Allows. Her character struck me not because of how she acted; I am pretty fond of smart and sassy women onscreen. Her character struck me because of how blatantly her character was dismissed by the other characters, especially the male characters but not exclusively. I have seen many movies that do not lend themselves to feminist values or represent women in an equal way, but I had grown accustom to the present luxury of films at least attempting to empower women in their roles onscreen. In the few scenes of All that heaven Allows we watched in class and the few more I have watched on my own, Kay’s sharp and witty comments did not earn her male attention (or attention at all). Her cute glasses and perky ponytail were constantly dismissed by the other characters as she was condemned for focusing so much of her time in academia and taking psychology so seriously. But this is what grabbed my attention. I chalked up her dismissal to a product of the time that the movie was released. In 1955, women were expected to play a certain role, in real life and this carried onto the screen. Women were expected to be physically beautiful, submissive, and not too smart.

Kay’s character, and the way she is treated onscreen, has evolved. Fortunately. Through the kind of forward-one-step-and-back-two-steps progress. Unfortunately. But as women have started to be valued at more than their face-value (literally) in society, their representation on screen and the role that nerdy women play in films has expanded. I will trace the evolution of the smart, nerdy female character from being completely dismissed by the characters and the plot to attracting the eyes of her fellow male characters and the audience—and more importantly how she expanded her role. Through this evolution, I will utilize characters who both strictly play the nerdy female role and characters who push the boundaries of this role, either from within the archetype or from the outside. For the purposes of this analysis (and because I just finished the series), I am going to identify Jessica Day from New Girl as the modern female nerd, a much sexier and less ignored but just as nerdy female character. On the shoulders of the many nerdy personas who came before her, Jess worked her way to the center of her own TV show. But did this nerdy girl have to change from how we saw her as Kay Scott to appeal to the audience enough to have her own show as Jessica Day?

Beauty over Brains

As I mentioned earlier, Kay’s character in All That Heaven Allows, was dismissed because she did not conform to what the film industry deemed valuable onscreen during the 1950s. Although the actress, Gloria Talbott, is definitely attractive by most beauty standards, the character she plays as Kay strips her of this stereotypical attractiveness as soon as she opens her mouth. Her know-it-all attitude and refusal to sit down and be quiet makes her unsuitable in the eyes of stereotypical men during the 1950s.[1] As female characters were usually displayed only in relation to the male characters, Kay’s lack of appeal to men forced her character to the sideline for the audience as well.

While actresses’ onscreen value was largely based on their physical attractiveness, their physical beauty did not guarantee their character’s value in terms of the plot if their character did not conform to the expected female persona. A smart female character lost attractiveness points if she was too knowledgeable in comparison to the man. This does not only explain why characters like Kay were dismissed in early films, but it also explains the value behind female characters who seem to add nothing (in dialogue or action) to the plot. The archetype of this counter-character that first comes to mind is: the Bond Girl. These stereotypically beautiful and sexy characters were a staple of the series during the sixties, but their cinematic role was limited to adding eye-appeal and (in a real stretch) romance to the film. While Bond Girls might be the extreme opposite of the nerd girl in film in terms of sexual exploitation and female expectations, they speak to how women have traditionally been used onscreen, and they explain why the nerdy girls were ignored in early films.

Brains over Beauty

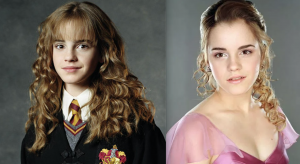

As I said earlier, the evolution of female characters was not completely linear chronologically. Smart women worked their way towards the core cast of the film, but never quite accomplished a center role without altering their character. Two examples of smart and even nerdy female characters who made their way to this intermediate role are Velma in Scooby Doo and Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter Series. These two characters were intermediate characters between the early intellectual female characters like Kay Scott who were completely eclipsed from the plot and the present nerdy women characters like Jessica Day who are at the center of the series. In order to cover the distance between this important but still secondary role and earn the spotlight of the main character, female characters must exude a certain sexiness or allure. Velma and Hermione are not yet exploited sexually, but this is at a cost: their lack of sexual attraction keeps them on the relative outskirts of the action. They are not the whole package. Their intellect contributes to the plot and helps the core group solve problems and realize situations, but they are only there to help, not to lead or to be sought after.

It could be argued that it is better for a female character to avoid the main character role if it means that she is able to maintain her dignity and avoid exploiting her sexuality. Even so, both Scooby Doo and the Harry Potter Series contain scenes where the Velma and Hermione undergo some sort of transformation and dress up for an event and their physical beauty is realized by the rest of the cast. It is only after this kind of scene where they are pursued by any male characters. So while their overall character may have escaped this exploitation, the notion that their desirability exists under their glasses and know-it-all comments adds another element to their character that brings them closer to the center of attention.

Transformation Genre

Along this same line of thought, if a smart or nerdy female character shows any sort of desire to attract a partner, it is nearly a given that she must undergo some sort of physical transformation, to conform to conventional beauty standards and attract another character. Even if the physical transformation is for another reason besides attracting another person, movies that portray a smart or capable female character who does not know how or care to make herself conventionally attractive usually have a physical transformation or “make-over” weaved into the plot, as if a woman is not fulfilling her full potential if she is not appealing as physically attractive as she is able to. Two films that demonstrate this type of movie are The Princess Diaries and Miss Congeniality. Honestly, I love both of these films, and while the motivator for the female character’s make-over is not completely motivated by winning over a love interest, both Gracie Hart and Mia Thermopolis are rewarded for their transformation with a man realizing her beauty and falling for her.

Kay Scott to Jessica Day

The film industry has come a long way from Bond Girl character types and blatantly ignoring Kay Scott’s character. Female characters are now leads in James Bond-esque movies, like Atomic Blonde, and classic super-hero movies, like Wonder Woman. While the characters of these movies would by no means qualify as nerdy, they definitely put smart, powerful women at the center of the plot. And it took a long time to get to that point. But what about those Kay Scott characters? The modern Kay Scotts have evolved into Jessica Day’s. Jessica Day is smart and quirky. She is a high school principal and she loves to knit. Her best friend is a super model, putting her in the classic juxtaposition with the conventionally beautiful and revered. She even wears glasses. These Jessica Day’s have made progress from the Kay Scott’s, if progress is measured in terms of attention, plot influence, and screen time. Their lines are no longer ignored or dismissed. The TV series may even be named after her.

But Jessica Day is also attractive. She may be partially hidden behind her glasses and thick bangs, but on more than one occasion she is dressed up for a date or an event and she exudes almost every quality of conventional beauty. She is pursued by multiple men, including her 3 male roommates. She is more quirky and naïve than conservative or prude. Oftentimes, she is sexy. The hints of allure that surface rarely in Velma and Hermione are more frequent in Jessica Day. Her nerdy glasses have become chic with the times, and with that, so have her many of her quirky qualities. But more so than the changing of times, it is her physical attractiveness that allows her to exist as a nerd in the center of her own show.

How and why did Kay Scott have to change in order to become Jessica Day? Now that I have provided a more complete picture of how this archetype of the nerdy girl evolved, I will look into how smart women are represented onscreen today, especially in relation to how they got there.

VIS 369 Final Paper- Miss Representation

[1] https://the-artifice.com/masculinity-gender-roles-tv-1950s/