In Visionary Feminism by bell hooks, hooks articulates that a major pitfall of modern* feminism is the movement’s failure to attempt genuine equality for all women in favor of ensuring the safety of those privileged enough to have ascended to power. The alternative to our flawed modern feminism, writes hooks, is the notion of visionary feminism. Visionary feminism shares ideals with previously explored feminist movements, but, true to its title, foregoes the constraints of modern society to explore a more visionary, inclusive feminist structure. To hooks, visionary feminism is a movement which cuts across women of all races, ethnicities, geographies, and socioeconomic statuses to seek myriad cultural, economic, and political forms of empowerment. Previous feminist movements, hooks argues, though good at heart, emphasized reformative reduction of economic discrimination to a detriment, “ultimately forsaking the radical heartbeat of the feminist struggle” and making the “movement more vulnerable to cooptation by mainstream capitalist patriarchy” (hooks, 111). Women at the forefront of the movement, who were often white and privileged, were “seduced by class power and/or greater class mobility once they made strides in the existing social order” and thus less “interested in working to dismantle that system” (111). These feminist concessions transformed the ideologically-inclusive feminist movement into a more pragmatic mutation, which abandoned radical revolution for the many, such as “mass-based feminist education” (113), in favor of economic security for the few.

hooks’ argument resonates with my own understanding of emergent intersectional feminism as an antidote for prior exclusive and classist feminist waves. The third wave feminist movement of the 90s, which hooks’ writing takes place at the midpoint of, sought to create a more inclusive movement which acknowledged the varying impacts of sexism along racial, ethnic, and class lines. Yet, the immediate impacts of this feminism feel distinctly theoretical and ideological, as opposed to physical. While first and second wave feminism resulted in more concrete societal changes, such as women’s suffrage and the near-passing of the ERA, third wave feminism, it seems, has had less tangible impacts for the everyday woman. This may be a consequence of third wave feminism’s observations and outcries of racial, ethnic, and class discrimination and sexism that require radical societal change to achieve. It seems that in many ways, heightened exposure of discrimination for these groups has been publicly coined as the movements “success” and more radical attempts to alter societal fabric have been consequently ditched. Thus, I was particularly drawn to hooks’ proposal of practical, intersectional feminist institutions in modern day society. The need for a “broad-based feminist movement” seems like a revelation to me, one which should be a natural progression of feminism but for some reason feels overly optimistic or out-of-touch (112). Why is it that the feminist movement has been unsuccessful in pushing feminist politics, in creating programs which benefit all women and alleviate intersectional discrimination? hooks argues that elite educations and classist greed can be attributed for this problem, as predominantly white, wealthy, well-educated women rise as powerful feminist thinkers, and these women often have little practical impact or desire to create broad-based change.

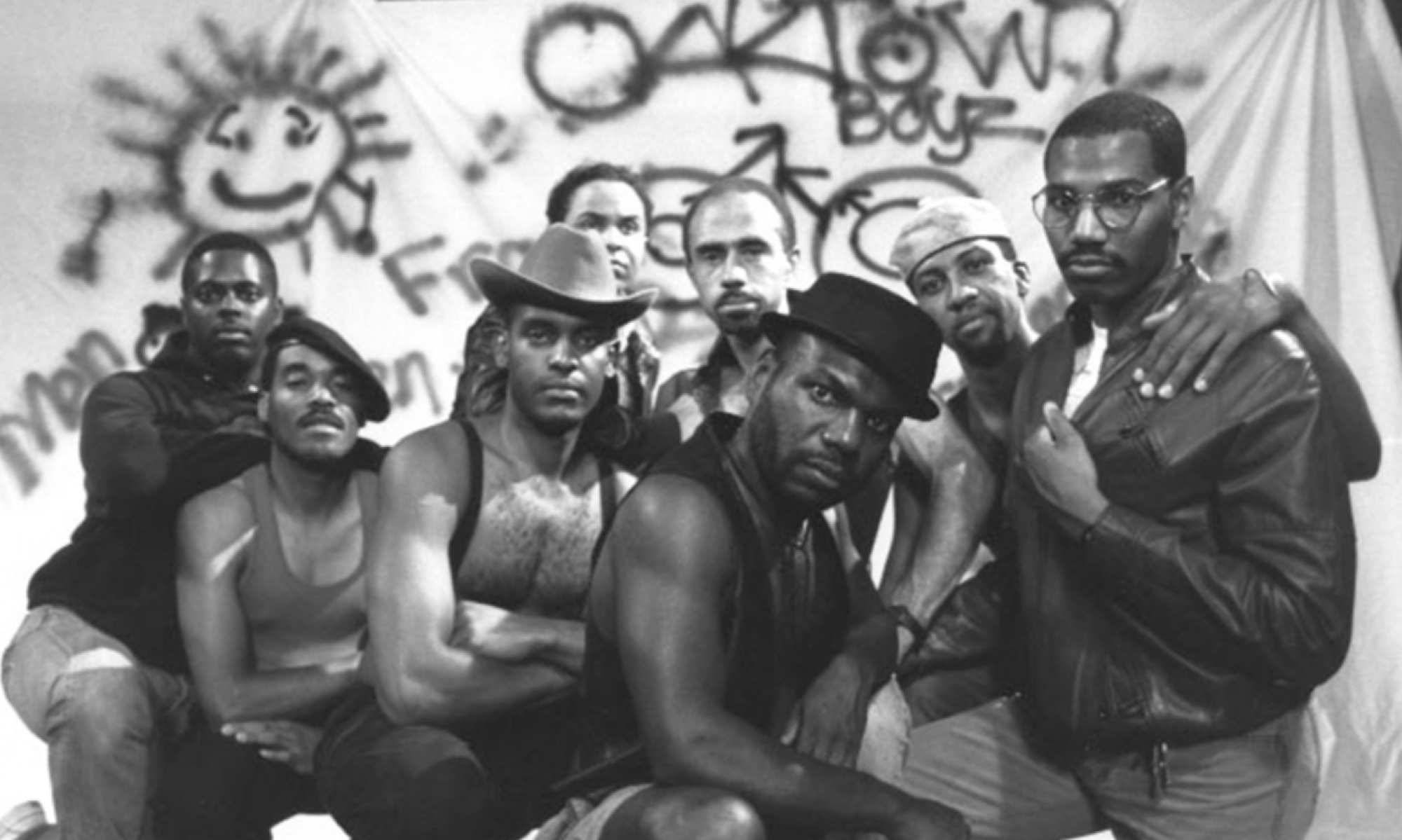

hooks’ concept of movement concession and class/racial subordination, though written twenty years later, is heavily reflected in Lizzie Borden’s film Born in Flames. Born in Flames explores a similarly “visionary” image of feminist comradery, as well as the feminist fragmentation prevalent in society. Set in a dystopian future society which has undergone a Social Democratic revolution, Born in Flames begs us to question our preconceived notions about what we consider “radical” and “progressive”, just like hooks does. While Leftism is often perceived as a champion of minority groups, Born in Flames demonstrates how progressive movements may be misconceived by the public as inherently egalitarian, even though such movements may still promote racial, sexual, and class oppression. The competing narratives of the white-narrated Radio Ragazza and black-narrated Pheonix Radio display a concrete division within the movie’s feminist base.

The movie also defines a privileged white-liberal elitist, pseudo-feminist base akin to that of hooks– the women who work for the press. As women are continually oppressed under the revolutionary regime, these groups come together under a broader movement, eventually working as a whole to promote female equality through terroristic and riotous means. Born in Flames demonstrates much of what hooks discusses—that many women will turn on feminism for economic security; that feminism is often codified by nuanced racial and class distinctions, which makes the broad movement less mobile and comprehensively successful; and that breaking down these barriers within the wider movement leads to enhanced success and even eventual female liberation. Its setting as a dystopian society utilizes the same sense of fantasy as hooks’ writing, using the imaginary to show us the flaws of the present. While Born in Flames provides a negative depiction of what may happen if women are unable to reconcile their own group’s success with the success of all women, Visionary Feminism shows us how we currently allow the patriarchy to control the outcome of feminism through economic and political diversion, and how women may supplant these limitations through visionary thinking. Both pieces of work– though one is a rowdy, punk-rocking handcrafted piece of shaky video and the other is a poised and concise written reflection—demonstrate how feminism limits itself through restricted perspective and begs us to ask—who deserves loyalty?

In modern day, both Visionary Feminism and Born in Flames remain relevant in our understanding of how and why feminism remains, in some ways, a limited social movement. For one reason or another, it seems that feminism has struggled to manifest itself in egalitarian action. Perhaps this says something about how we view matters of gender and sexual identity in comparison to other societal and cultural identifiers, or perhaps, as we discussed in class, visionary feminism is inherently at odds with capitalist culture. This argument is compelling, yet Born in Flames again threatens this assumption—if capitalism is at odds with feminism, wouldn’t a more egalitarian structure, like socialism, be conducive to gender equality? Both hooks and Borden’s pieces make us question how competing feminist factions may inhibit women’s progress, and question the cultural divides that seem to supersede feminist causes for many women. While I am unsure of how to answer the contradictions posed by either piece [feminist terrorism, though radical in the movie, is not the right choice in reality; nor does a “collective door to door effort” (hooks) seem fitting for modern day], I do think that they aptly highlight how and why myriad societal and cultural barriers make visionary, inclusive feminist realities feel so out of reach– and hint at ways we may overcome these divisions.

*hooks’ piece was written in 2000