Ana Sotomayor delves into what “home” means for undocumented immigrants in the U.S., and how changing laws impact that relationship.

Full description:

For undocumented immigrants in the United States, defining home can be paralyzing. And that question is changing along with the laws. The Senate is currently weighing “The American Dream and Promise Act,” which would grant permanent residency to millions of eligible immigrants and, after a decade, citizenship. For many undocumented people, these changes would dramatically change their relationship to home. This is a story about how to find home when it’s not legally recognized.

Credits / show notes:

Episode by Ana Sotomayor. Sounds from Hermanos Carrion, the Free Sound Library, C-SPAN. Audio via Monica Patino and Maria Restrepo.

Transcript:

HOST INTRODUCTION: The idea of home is complicated.

(Questions trade off between multiple hosts) Is it somewhere I’m safe? Is it a person? Is it a

feeling? Is it a place?

For undocumented immigrants in the United States, defining home can be paralyzing. And that

question is changing along with the laws. The Senate is currently weighing “The American

Dream and Promise Act,” which would grant permanent residency to millions of eligible

immigrants and, after a decade, citizenship.

For many undocumented people, these changes would dramatically change their relationship to

home. Ana Sotomayor has the story about how to find home when it’s not legally recognized.

We’ll follow one of those immigrants as she journeys to answer this question.

ANA SOTOMAYOR: An estimated eleven million people in the United States are undocumented.

They’re here for many reasons. Some are escaping the dangerous conditions of their birth

countries and others come to reunite with their families. But one thing they all have in common

is how challenging it is to define home.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO OF REPORTING 2004 GEORGE BUSH VICTORY — have a little bit before

(longer) in “grappling”

I’ve been grappling with this question for most of my life.

It started back in 2004. In the United States, George Bush just won the presidency for the

second time. In Peru, I’m holding my grandma’s hand. We’re headed to the airport, and I don’t

know what we’re doing but everyone’s saying goodbye. I remember it went something like this:

MARIA RESTREPO (STAND-IN FOR GRANDMOTHER’S VOICE):

Vas a ver a tu mami. Cuando entras al avión, no les digas tu nombre.

MONICA PATINO (TRANSLATING):

You’re going to see your mom. When you enter the plane, don’t tell them your name.

SONIA PALOMINO:

Negaron la visa tuya, entonces solamente nos permitian a nosotros dos salir y tú te quedabas.

Fue muy triste, muy doloroso, a ver de que no te lo otorgaban a ti.

MONICA PATINO (TRANSLATING):

They denied your visa application. They only allowed us to leave, and you stayed. It was really

sad and painful that they didn’t grant it to you.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

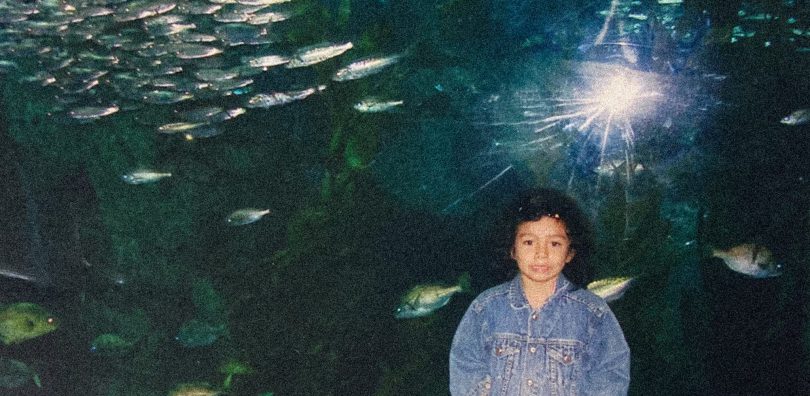

I left Perú when I was four, and I hold the very few memories close to my heart. But ever since I

got off that plane into the United States, I’ve been undocumented.

My story is one in millions. I’m curious to know how undocumented immigrants have created

their own understandings of home in a country that sometimes feels like it doesn’t want them.

What is belonging to the undocumented person? What are their stories of arrival?

I call Maria Perales. She came from Mexico when she was eight. She still remembers it vividly.

PHONE DIAL AUDIO —

MARIA PERALES:

When we were leaving our little hometown to immigrate to the U.S., they were playing this really

sad song. So, I know that song to this day, and it was raining also. But when we arrived, we

arrived at night and the first thing that I did was hug my mom.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

And do you remember the name of that song?

MARIA PERALES:

Lagrimas de Cristal.

MONICA PATINO (TRANSLATING):

Crystal tears.

LAGRIMAS DE CRISTAL AND RAIN SOUND EFFECT AUDIO —

MARIA PERALES:

De las lágrimas de cristal, que derramamos al partir. Which, al partir is like “once we left.” It was

very, very touching.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

What came after “Crystal Tears” was joy. Maria reunited with the rest of her family who had been

living in the United States for a long time. She saw her dad for the first time in years. One of

nine children, Maria would finally see them all under one roof in Texas. They made the journey

worth it.

MARIA PERALES: In many ways, I had never felt any shame because I felt that the reasons that we’re

coming—the reasons my mom explained to me—made sense.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

I can imagine that, like, at eight years old, you’re thinking, “I just want to see my parents.”

MARIA PERALES:

Right! Right.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

For Maria, immigrating to the United States acted as a homecoming. It wasn’t about a shiny,

new country, but rather, it was about reuniting with family.

For others, it’s a different experience. It’s actually escaping a dangerous situation.

I call someone whose homeland turned violent. For fears of retribution, they wanted any

identifiers to stay secret.

They shared some of the most harrowing tactics of suppression their country’s government was

using against its people. From murders to kidnappings to human trafficking, their country takes

censorship to another level. They know their family would be targeted.

They tell me, quote, “If we go back, we might get killed… and add to that, the government is

targeting anyone they think they could ransom for money,” unquote.

They echo their father’s words in choosing to stay undocumented in the United States. Quote,

“If something happened to the kids, it’d be my fault,” unquote.

There are many stories like this, but nobody knows the true numbers. We do know how many

tried to leave their home countries and died on the journey. According to the World Migration

Report, 30,000 between 2014 and 2018. What we don’t know is how many are still alive.

The thing about immigration is that we’re more than numbers, patterns, trends. We come as

living archives. Hearing from these undocumented immigrants makes me wonder more about

my story. What I was thinking when I came here?

It turns out, no one knows. I had a speech impediment and hardly even spoke. My mom

remembers.

SONIA PALOMINO:

Ni palabras, Mariana, tú solamente decias “mmm, mmm, mmm, mmm.” No hablabas. Cuando

llegó Ana a los Estados Unidos, de solamente hacer una sílaba, ella era una lora al hablar.

Hablaba demasiado.

MONICA PATINO (TRANSLATING):

You didn’t even say words. You would only say “_____” (said by mother). When you came to the

United States, from saying one syllable, you became a chatterbox. You talked so much.

ANA SOTOMAYOR:

And I never had a problem with speech after that.

Learning English opened new doors for me. My mom shares how I dreamt of meeting Santa

Claus, who was real in los estados unidos, so I had to learn to communicate. How else could I

tell him what I wanted for Christmas?

I can’t remember what item was under the tree that year, but I can point to something I got the

year I immigrated. It was the gift of language.

After talking to other undocumented immigrants about redefining home, I feel less paralyzed

answering this question for myself. Home is… feeling free to speak and be heard. And even

though laws are changing and citizenship is getting closer and closer, I’ll always find home in

having a voice.

This is Ana Sotomayor, signing off.