Passage for Emphasis – Othello

IAGO

Demand me nothing: what you know, you know:

From this time forth I never will speak word.

LODOVICO

What, not to pray?

GRATIANO

Torments will ope your lips.

OTHELLO

Well, thou dost best.

LODOVICO

Sir, you shall understand what hath befall’n,

Which, as I think, you know not. Here is a letter

Found in the pocket of the slain Roderigo;

And here another: the one of them imports

The death of Cassio to be undertook

By Roderigo.

OTHELLO

O villain!

CASSIO

Most heathenish and most gross!

LODOVICO

Now here’s another discontented paper,

Found in his pocket too; and this, it seems,

Roderigo meant to have sent this damned villain;

But that belike Iago in the interim

Came in and satisfied him.

OTHELLO

O the pernicious caitiff!

How came you, Cassio, by that handkerchief

That was my wife’s?

CASSIO

I found it in my chamber:

And he himself confess’d but even now

That there he dropp’d it for a special purpose

Which wrought to his desire.

OTHELLO

O fool! fool! fool!

CASSIO

There is besides in Roderigo’s letter,

How he upbraids Iago, that he made him

Brave me upon the watch; whereon it came

That I was cast: and even but now he spake,

After long seeming dead, Iago hurt him,

Iago set him on.

LODOVICO

You must forsake this room, and go with us:

Your power and your command is taken off,

And Cassio rules in Cyprus. For this slave,

If there be any cunning cruelty

That can torment him much and hold him long,

It shall be his. You shall close prisoner rest,

Till that the nature of your fault be known

To the Venetian state. Come, bring him away.

OTHELLO

Soft you; a word or two before you go.

I have done the state some service, and they know’t.

No more of that. I pray you, in your letters,

When you shall these unlucky deeds relate,

Speak of me as I am; nothing extenuate,

Nor set down aught in malice: then must you speak

Of one that loved not wisely but too well;

Of one not easily jealous, but being wrought

Perplex’d in the extreme; of one whose hand,

Like the base Judean, threw a pearl away

Richer than all his tribe; of one whose subdued eyes,

Albeit unused to the melting mood,

Drop tears as fast as the Arabian trees

Their medicinal gum. Set you down this;

And say besides, that in Aleppo once,

Where a malignant and a turban’d Turk

Beat a Venetian and traduced the state,

I took by the throat the circumcised dog,

And smote him, thus.

(5.303-356)

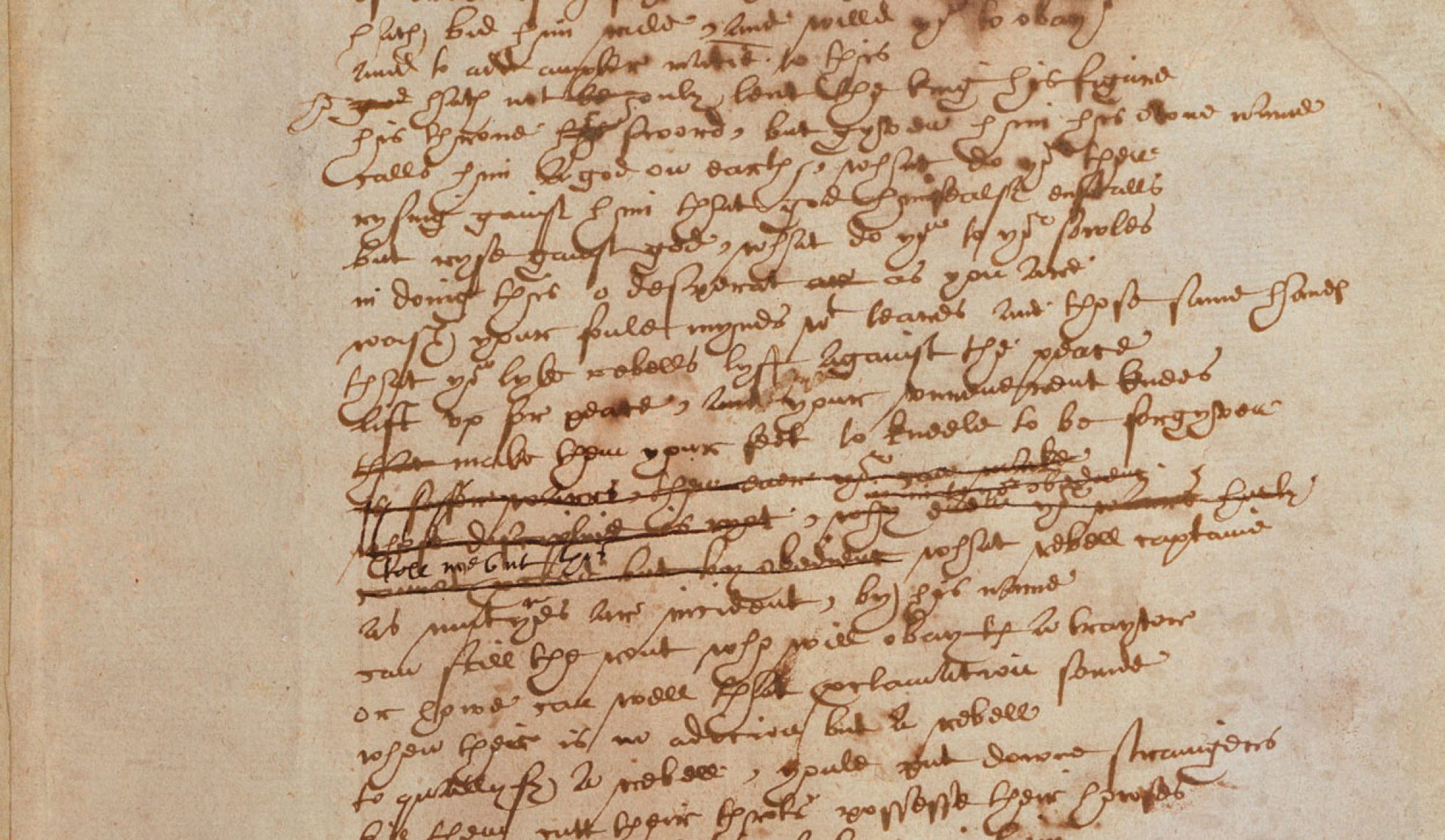

This passage interests me for its interplay between spoken and written word, between hearing and reading as ways of receiving information. I also want to consider the association between sound and character.

I want to begin by thinking about Iago’s self-sworn silence: Iago is the second-most vocal character in Shakespeare’s plays, with 1088, almost 25% more than Othello’s still-considerable 880 lines.[1] I am not sure if this effect is noticeable while reading the play, and I would like to pose to the class whether this effect is noticeable while hearing the play. We think of Othello as an especially eloquent character – and his rhetorical flourishes of elaborate imagery and diction bear this out – but it seems plausible that the predominance of Iago’s voice might relate to the predominance of his influence in the play, perhaps operating at a much more fundamental register than merely his ability to influence the outcomes of the plot. Iago is, in many respects, a narrator, describing what we, or the other characters of the play, see: most prominently in his orchestration of what Othello sees and hears in 4.1 – but also earlier in that scene of what Cassio (and the audience) sees, his lie that “this is his second fit; he had one yesterday” (4.1.51) easily escapes notice.

What is left, then, when that narration is silenced? This passage at first seems to place ultimate explicative power in the written form by accounting for the “discontented paper” of “Roderigo’s letter,” but Othello’s direction to the Venetians pairs the spoken and written forms of communication. He says to “speak of me” in “letters,” to “set down” and “must you speak” and to “set you down this; and say besides” blurs the boundaries between written and spoken text. For Othello, the written account has itself power to speak, and this raises the question of sound a text itself might have. In films often when a character reads a letter one hears the voice of the writer; this is very different that how the recipient of the letter reads a letter aloud in a play (e.g. Othello’s letter-reading in 4.1). What happens, however, when we read to ourselves in private? Do we read in our own voice, and if so, do we do so exclusively, without “doing the voices” as a child might say in response to a bedtime story read aloud? And if we read only in our own voice, what is the effect of replacing all the different characters’ voices with only our own “fingerprint,” to use Dolar’s metaphor for the uniqueness of individual voices (545)? Although Dolar asserts that the uniqueness of voices “does not contribute to meaning,” I find this claim difficult to reconcile with the clear association in a play with voice and character; one potential counterexample would be that of a back-row, or very short, ground-floor audience member in the Globe who might not be able to see the action and thus would rely solely on hearing. I think this latter situation is analogous in to the silent experience of private reading – if it were not for indentations and character labels (i.e., features of the play that do not contribute to the meaning of the play), our silent reading experience would be as though hearing the play without the distinguishing characteristics of different voices.

[1] Hamlet, is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most vocal with 1506 lines. http://www.shakespeareswords.com/Special-Features-All-Characters