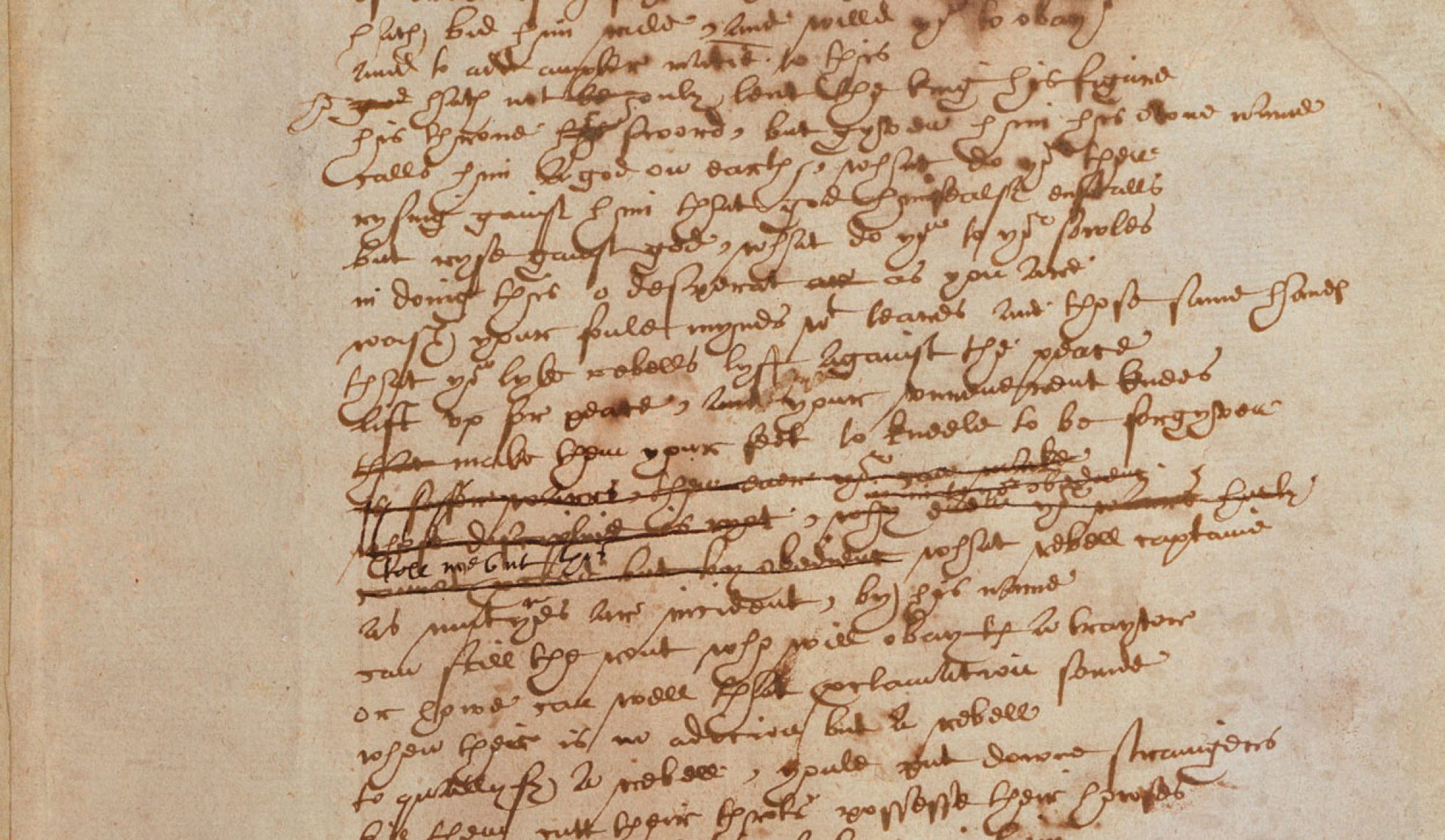

Act 1 Scene 2

PRINCE HENRY

I know you all, and will awhile uphold

The unyoked humour of your idleness:

Yet herein will I imitate the sun,

Who doth permit the base contagious clouds

To smother up his beauty from the world,

That, when he please again to be himself,

Being wanted, he may be more wonder’d at,

By breaking through the foul and ugly mists

Of vapours that did seem to strangle him.

If all the year were playing holidays,

To sport would be as tedious as to work;

But when they seldom come, they wish’d for come,

And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.

So, when this loose behavior I throw off

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glittering o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend, to make offence a skill;

Redeeming time when men think least I will.

Given the readings this week, I thought it might be worth thinking about how Shakespeare holds Hal together in Henry IV Part 1 in spite of the duplications of his character across many different contexts and forms. Hal with Falstaff and Hal with his father seem like two different characters. The form and texture of the language attest to this, moving from talking about animal parts in prose to glory in pentameter. There is also Hal as conveyed to Hotspur and Hal on the king’s mind—third-person descriptions a la Bal. If we are to think of Hal, not as a verisimilitude of a historical person but rather a “paper person,” as Mike Bal put it, and a body of text, what makes us think that his lines belong together? Why does it not feel incoherent?

In thinking about the question, I thought we may look at Hal’s soliloquy above. Here, Hal speaks alone, without the modulation of any other character. This is supposedly, his unadulterated self free from the bonds of having to banter with Falstaff or play prince to the king. If we were to look anywhere for the true Hal, the one behind the mask that juggles the wide range of language he exhibits in the play, it would seem to be here.

So what do we have? We have Hal speaking, for the first time, in verse. The image is naturalistic and the lines are of a high style. We only need to compare with the register he adopts with Falstaff. It does seem that Hal merely “permit[s] the base contagious clouds,” such that “being wanted,” “he may please again to be himself” and “be more wonder’d at.” He seems to convince us that his lifestyle is a choice by showing us that he can speak in high pentameter as well as the textured prose of Falstaff.

Hal also displays a keen sense of theater. “If all the year were playing holidays / To sport would be as tedious as to work,” he tells us, arguing that “nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.” Here, Hal speaks in verse for the first time, and I do think it has the effect he describes within his soliloquy; it contrasts powerfully with what we have been provided with thus far. The same sense of presentation runs through the ruse he plays on Falstaff, leading Falstaff on to bolster his claims only to undercut him more effectively later.

Is this enough? It still seems to me that lines being grouped under “Prince Henry” contributes the greatest to letting us think of them under a single unit of character.

Which leads me to wonder also whether this passage or a passage at all is the correct moment for thinking about what makes Hal a distinctive character. Maybe this is not the right way to go about it, trying to identify a core aspect stripped of other devices, but rather, we may consider the devices in their total effect. That is to say, there is no character element to be dug up, but character is the effect of all these devices given together.

But that also seems a little atemporal. The tense shifts to the future within the soliloquy around the middle when Hal talks about expectations: “But when they seldom come, they wish’d for come, / And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents. /So, when this loose behavior I throw off /And pay the debt I never promised.” Hal is not only aware of the expectations placed upon him as a prince but also when he will have to deliver them the most, when he becomes king. Expectations project from one point to another. And throughout the play, Hal’s character can be thought of as a shift from frustration of expectations to their fulfillment, and thus requires “Redeeming time” to be considered fully. That is to say, perhaps the problem of Hal may not only be the coexistence of different kinds of stylistic registers but also the order in which they shift and why. For example, why then, is this soliloquy not more delayed for greater effect? More fundamentally, can we consider character apart from plot?

-Jeewon

On a side note, during Richard II, we briefly discussed what rhetorical properties Richard and Bolingbroke had and how they were compatible for kingship and rule. In a play constantly concerned about roles, whether one is playing it correctly—whether the right person is performing it—Hotspur is entertained as Hal’s rival for fulfilling the role of a prince better, but perhaps the point of departure here may be that fulfilling one’s role well, fulfilling expectations, may not be what a good king or a character/actor does.