This highlights once again how crucial it is that schools be built to offer the best possible opportunities for their students. It also connects to Moses’ discussion of his nephew’s schooling and how crucial it is that education systems are effective.

Source: Elkins

Moses’ initial reaction is rooted in centuries of societal, conditioned stigma. “Historically, addiction was perceived as a moral failing of the individual, with the identification that persons acted voluntarily in the search of and continued use of drugs and that personality flaws were the explanation for the inability to cease use” (Santoro & Santoro). This mindset and misconception is also the reasoning surrounding the War on Drugs.

Click Here to Learn more about the stigma surrounding drug usage

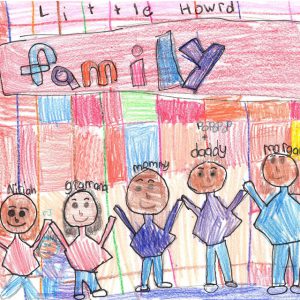

A picture celebrating family drawn by Sandy Plains Elementary School fourth-grader, Simone. Source: Sachs

A common theme throughout this interview is the importance Moses places on the neighborhood as a family, as well as his emphasis on his own family history in relation to the drug epidemic. He seems to regard sound family structures as essential for the success of a community.

While not a John Wanamaker factory, this Star Mill carpet factory in Kensington closed in the mid-20th century (Elesh)

Photograph by Mikaela Maria for “The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia”

Alyssa Ribeiro Reports that: “After the Great Depression, Puerto Rican government officials increasingly encouraged migration off the island, partly to address their perception that overpopulation exceeded economic resources. Officials facilitated employment contracts, arranged air transportation, and oversaw workers through regional offices. From the early 1940s to the early 1960s, tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans became seasonal workers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania” (Ribeiro).

This experience highlights the distrust of the police that many people of color feel. Additionally, Moses’ statement displays that this tension is one of the many hurdles that must be overcome in order to implement policy geared towards diminishing the tragic effects of mass incarceration and the war on drugs on communities of color. Regarding proposals for opioid-epidemic combatting programs involving police (Pre-arrest diversion), many worry about “giving law enforcement too much power when they’ve caused much damage through the war on drugs, which has been waged against communities of color in urban centers” (Wolfram, “In Kensington, Police Offer Drug Users Help Instead of Criminal Charges”). However, re-imaging how law enforcement operate and engage with community members is essential to mitigating the damaging effects of addiction and the current drug crisis.

“A view of West Kensington from inside Sheppard, near the epicenter of Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic.” (Heather Khalifa/Staff Photographer)

According to an article from the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Sheppard School’s performance “… over the last several years, a new principal and her team have brought new energy to the school. Now, the school is a place where teachers stay; turnover is improving. In 2017-18, three-quarters of the staff were the same as the year before. For 2018-19, that climbed to 85 percent — up from just 50 percent in 2012.”

(Calefati, Graham, Purcell)

Click here to learn more about changes to the Sheppard School.

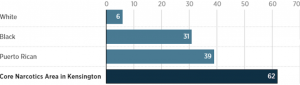

Puerto Ricans in Kensington are especially vulnerable to violence. Racial tensions in Philadelphia have led to “Puerto Rican territory” being viewed as a “neutral racial meeting ground” and consequently more white heroin customers flooded the drug market in the neighborhood, “happy to avoid black neighborhoods” where they felt less comfortable and would stand out more to police (Gutman).

This image illustrates the addiction cycle, reinforcing how difficult it is to overcome substance abuse disorders without resources. Source: “Breaking the Cycle of Addiction by Changing Past Behaviors”

Insisting that drug users go to rehabilitation centers in order to avoid prosecution could have a positive impact, but just being clean for several weeks does not mean that someone is no longer addicted. It does not guarantee that they will be less likely to be affected by drug violence within their neighborhoods.