5.1.21-131

ISABELLA

Justice, O royal Duke! Vail your regard

Upon a wronged—I would fain have said, a maid.

O worthy prince, dishonor not your eye

By throwing it on any other object

Till you have heard me in my true complaint,

And given me justice, justice, justice, justice!

DUKE

Relate your wrongs. In what, by whom? Be brief.

Here is Lord Angelo shall give you justice;

Reveal yourself to him.

ISABELLA

O worthy Duke,

You bid me seek redemption of the devil.

Hear me yourself, for that which I must speak

Must either punish me, not being believed,

Or wring redress from you. Hear me, O hear me, here!

ANGELO

My lord, her wits I fear me are not firm.

She hath been a suitor to me for her brother

Cut off by course of justice—

ISABELLA

By course of justice!

ANGELO

And she will speak most bitterly and strange.

ISABELLA

Most strange, but yet most truly will I speak.

That Angelo’s forsworn, is it not strange?

That Angelo’s a murderer, is’t not strange?

That Angelo is an adulterous thief,

An hypocrite, a virgin-violator,

Is it not strange and strange?

DUKE

Nay, it is ten times strange.

ISABELLA

It is not truer he is Angelo

Than this is all as true as it is strange.

Nay, it is ten times true, for truth is truth

To the end of reckoning.

DUKE

Away with her. Poor soul,

She speaks this in the infirmity of sense.

ISABELLA

O prince, I conjure thee, as thou believ’st

There is another comfort than this world,

That thou neglect me not with that opinion

That I am touched with madness. Make not impossible

That which but seems unlike. ‘Tis not impossible

But one the wicked’st caitiff on the ground

May seem as shy, as grave, as just, as absolute,

As Angelo. Even so may Angelo,

In all his dressings, caracts, titles, forms,

Be an arch-villain. Believe it, royal prince.

If he be less, he’s nothing; but he’s more,

Had I more name for badness.

DUKE

By mine honesty,

If she be mad, as I believe no other,

Her madness hath the oddest frame of sense,

Such a dependency of thing on thing,

As e’er I heard in madness.

ISABELLA

O gracious Duke,

Harp not on that, nor do not banish reason

For inequality, but let your reason serve

To make the truth appear where it seems hid,

And hide the false seems true.

DUKE

Many that are not mad

Have sure more lack of reason. What would you say?

ISABELLA

I am the sister of one Claudio,

Condemned upon the act of fornication

To lose his head, condemned by Angelo.

I, in probation of a sisterhood,

Was sent to by my brother; one Lucio

As then the messenger—

LUCIO

That’s I, an’t like your grace.

I came to her from Claudio, and desired her

To try her gracious fortune with Lord Angelo

For her poor brother’s pardon.

ISABELLA

That’s he indeed.

DUKE (to Lucio)

You were not bid to speak.

LUCIO

No, my good lord,

Nor wished to hold my peace.

DUKE

I wish you now then.

Pray you take note of it, and when you have

A business for yourself, pray heaven you then

Be perfect.

LUCIO

I warrant your honour.

DUKE

The warrant’s for yourself, take heed to’t.

ISABELLA

This gentleman told somewhat of my tale.

LUCIO

Right.

DUKE

It may be right, but you are I’ the wrong

To speak before your time. (To Isabella) Proceed.

ISABELLA

I went

To this pernicious caitiff deputy—

DUKE

That’s somewhat madly spoken.

ISABELLA

Pardon it;

The phrase is to the matter.

DUKE

Mended again. The matter; proceed.

ISABELLA

In brief, to set the needless process by—

How I persuaded, how I prayed and kneeled,

How he refelled me, and how I replied,

For this was of much length—the vile conclusion

I now begin with grief and shame to utter.

He would not but by gift of my chaste body

To his concupiscible intemperate lust

Release my brother; and after much debatement,

My sisterly remorse confutes mine honour,

And I did yield to him. But the next morn betimes,

His purpose surfeiting, he sends a warrant

For my poor brother’s head.

DUKE

This is most likely!

ISABELLA

O that it were as like as it is true.

DUKE

By heaven, fond wretch, thou know’st not what thou speak’st,

Or else thou art suborned against his honour

In hateful practice. First, his integrity

Stands without blemish; next, it imports no reason

That with such vehemency he should pursue

Faults proper to himself. If he had so offended,

He would have weighed thy brother by himself,

And not have cut him off. Someone hath set you on.

Confess the truth, and say by whose advice

Thou cam’st here to complain.

ISABELLA

And is this all?

Then, O you blessed ministers above,

Keep me in patience, and with ripened time

Unfold the evil which is here wrapped up

In countenance! Heaven shield your grace from woe,

As I, thus wronged, hence unbelieved go.

DUKE

I know you’d fain be gone. An officer!

To prison with her.

Isabella is arrested

Shall we thus permit

A blasting and scandalous breath to fall

On him so near us? This needs must be a practice.

Who knew of your intent and coming hither?

ISABELLA

One that I would were here, Friar Lodowick. (Exit with Officers)

DUKE

A ghostly father, belike. Who knows that Lodowick?

LUCIO

My lord, I know him, ‘tis a meddling friar.

I do not like the man; had he been lay, my lord,

For certain words he spake against your grace

In your retirement, I had swinged him soundly.

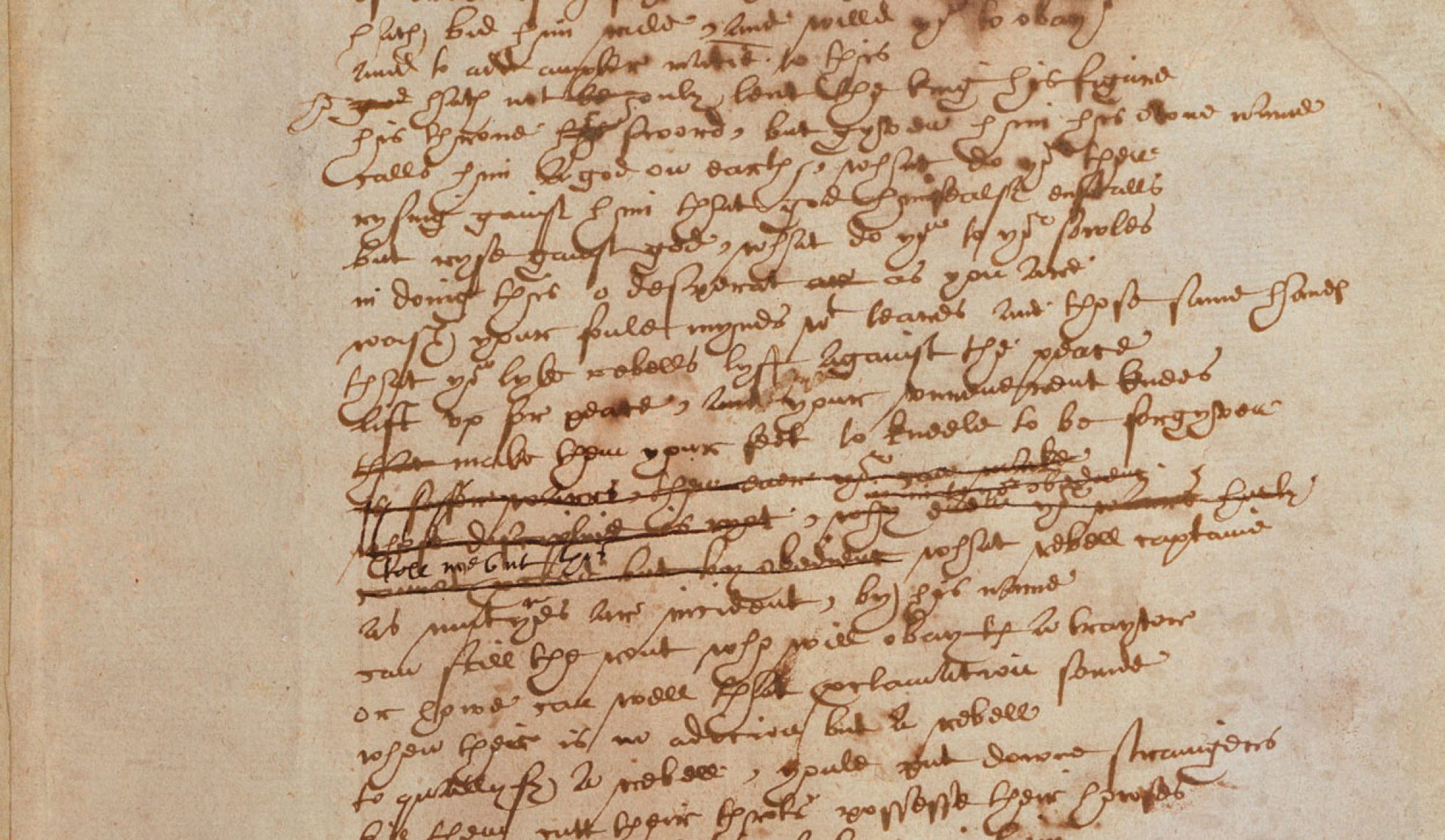

Although this passage is a relatively long one, it seemed fitting to propose that we discuss Isabella’s complaint before the Duke, given some rather obvious resonances with some of the secondary reading for this week (particularly the Foucault).

As Isabella brings her complaint before the Duke, Angelo immediately attempts to discredit her by portraying her as mad—thus removing her from “the common discourse of men,” as Foucault would have it (217), but also running straight into the dangerous potential for interpreting madness as a “rationality more rational than that of a rational man” (217). The Duke repeatedly notes that her discourse does not bear the appearance of madness, a comment which could of course lend itself either to the conclusion that she is not mad or to the possibility that her madness is simply the vehicle of a higher truth. Meanwhile, Isabella herself recognizes the difficulty of pleading her case and characterizes the matter repeatedly in terms of “strangeness,” calling upon divine power to verify that despite running contrary to institutional authority and expectations, the “truth” of what she is saying is so pure that it must be recognized. There seems even to be something oddly transactional about this use of “strange” and “true,” with Isabella and the Duke even bringing multiplication into the mix to describe the magnitude of the discourse’s transgression/truth, and the Duke later suggesting that justice would “weigh” Claudio’s behavior against Angelo’s.

Lucio provides an interesting counterpoint to Isabella, interrupting her complaint in an attempt to corroborate the facts but being repeatedly shut down by the Duke, who criticizes him on the level of form (while granting the possibility that what he says may be “right”): regardless of whether Lucio is telling the truth, his speech is rejected by the representative of the judicial institution. (The interruptions also recall Lucio’s repeated interventions during Isabella’s initial interview with Angelo, pushing her to argue harder or approving her rhetoric from the sidelines, but remaining in that case unacknowledged.) Even more interesting, though, might be the way he attempts to play the situation at the end of this passage, once Isabella has left and the Duke finally turns his attention to him. Projecting his own controversial comments onto the Duke’s alter ego, Lucio undermines the authority of Isabella’s witness while the victim’s honesty is still threatened (thus also undermining the authority of a character he might expect to get him in trouble himself). In a sense, this hypocrisy mirrors the fault of Angelo, who prosecutes Claudio unjustly even after “weighing” himself against the convict in order to prevent Claudio from returning to complain on his sister’s behalf. Just as Angelo breaking his promise to Isabella multiplies his guilt (or should; the play retreats from this intensification and seems to justify it at a structural level through Angelo’s actual failure to kill Claudio, although this moves the ‘justice’ portrayed in the play away from its more typical portrayal of the state as a sort of guardian of ethics), Lucio’s attempt to shift the blame to the disguised Duke really just doubles his slander against the same person.