II. 2. 107-110

ISABELLA

So you must be the first that gives this sentence,

And he, that suffer’s. O, it is excellent

To have a giant’s strength; but it is tyrannous

To use it like a giant.

…

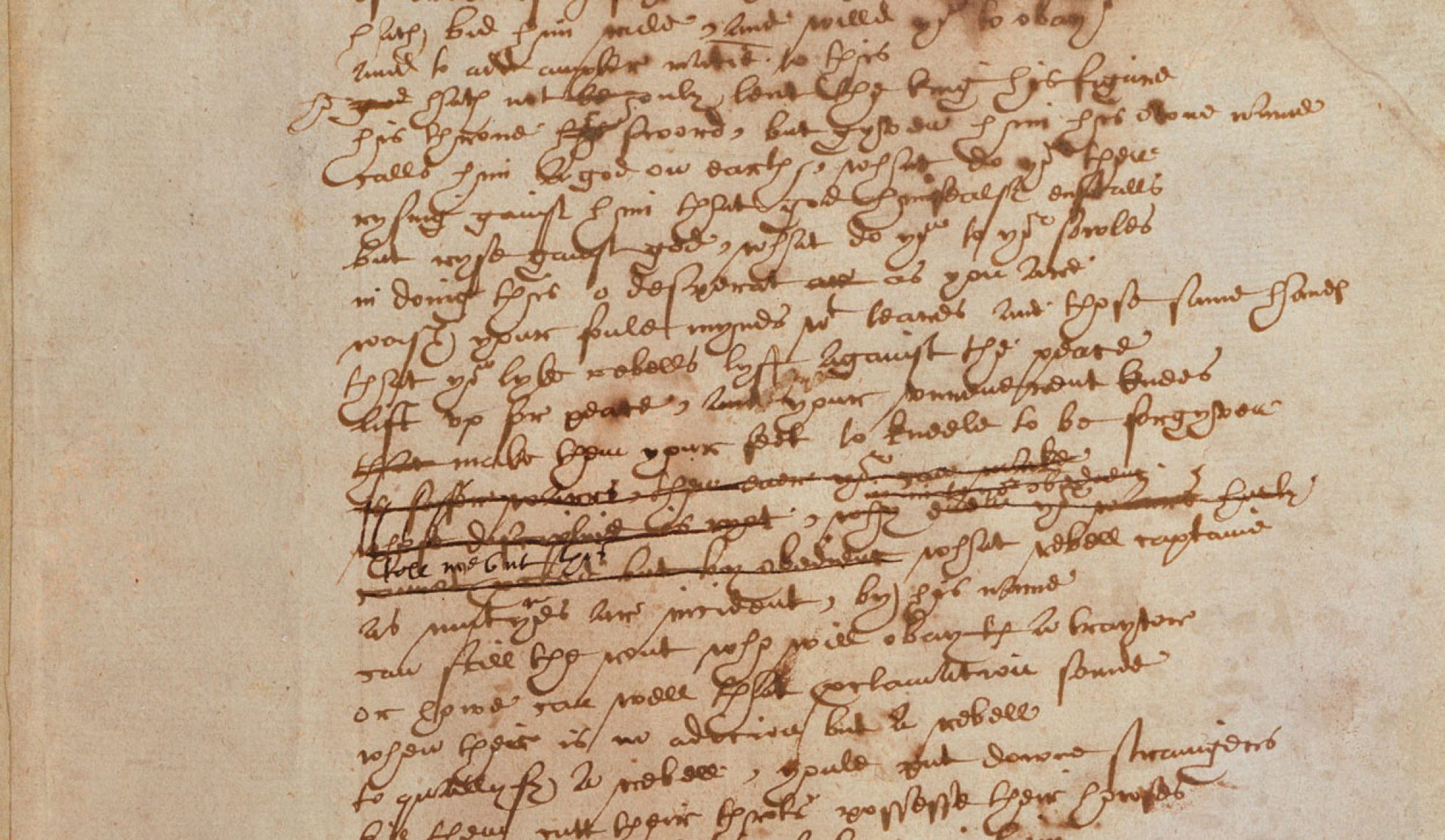

II. 4. 115-148

ANGELO

You seem’d of late to make the law a tyrant;

And rather proved the sliding of your brother

A merriment than a vice.

ISABELLA

O, pardon me, my lord; it oft falls out,

To have what we would have, we speak not what we mean:

I something do excuse the thing I hate,

For his advantage that I dearly love.

ANGELO

We are all frail.

ISABELLA

Else let my brother die,

If not a feodary, but only he

Owe and succeed thy weakness.

ANGELO

Nay, women are frail too.

ISABELLA

Ay, as the glasses where they view themselves;

Which are as easy broke as they make forms.

Women! Help Heaven! men their creation mar

In profiting by them. Nay, call us ten times frail;

For we are soft as our complexions are,

And credulous to false prints.

ANGELO

I think it well:

And from this testimony of your own sex,–

Since I suppose we are made to be no stronger

Than faults may shake our frames,–let me be bold;

I do arrest your words. Be that you are,

That is, a woman; if you be more, you’re none;

If you be one, as you are well express’d

By all external warrants, show it now,

By putting on the destined livery.

ISABELLA

I have no tongue but one: gentle my lord,

Let me entreat you speak the former language.

ANGELO

Plainly conceive, I love you.

The lines reproduced above are a part of the tug-of-war between Isabella and Angelo. She asks for an abeyance of the law and he, of her chastity. The two discursive domains intersect in the social form of a woman’s plea. The form is a familiar one to our characters, for some of them even meddle with instructions on how to plead effectively. Within the scene, however, I want to focus on the bolded phrase and think about how this statement arises, why it is accepted as legitimate, how the response melds the discourse of law and love, whether the response appears elsewhere in different form.

I want to think of “we speak not what we mean” as a metadiscursive act, one that not only references and describes a feature of the conversation at hand (pleading, making a case) but also functions as a discursive move on its own (analogous to but different from Berger’s meta theatrical). Which is a long-winded way of saying the line falls into the category of things we say about what we say while saying them—“It’s hard to understand you,” “Let me clarify,” “Do you see what I mean?,” and etc. I think this feature of the line is important because it is a way of staying within a discussion and stepping out of it, of participating and observing one’s participation in a discourse. We might care to keep this mind for when we might introduce Berger’s ethical questions.

We may read “we speak not what we mean” as acknowledging a failure in communication—one that can be corrected through perhaps elaboration, clarification, or even substitution. But we might also read the line as being reflective of unwanted success. Isabella delivers her meaning too well: Angelo is being a tyrant, and Claudio, a mere lover. But the resulting claim is untenable in a plea for mercy, so Isabella must retract them. That is to say, we might gloss the line not only as “What I mean to say was—“ but also as “That is not what I meant,”

(In the midst of argument, we say something, and our interlocutor offers a paraphrase of our own words, harsher but closer to truth in form. But it looks too grave, too terrible for us. We cannot be responsible for such a statement. So we disavow the paraphrase and along with it, our original statement, but the effect of them linger. This is how we say true and terrible things, by not saying them, by making our interlocutor say them, by appending “That is not what I meant.” We hear in return, “Yes, it is.”)

So Angelo accuses Isabella: “You seem’d to make the law a tyrant; / And rather proved the sliding of your brother / A merriment than a vice.” And so she disavows. Foucault might say that Angelo’s paraphrase, though accurate, cannot be admitted into the discourse of the plea. Isabella’s plea is predicated upon already determined truths: Claudio has broken the law. Claudio must die. Angelo enforces the law. Angelo must execute Claudio. Isabella introduces her plea into this legal discourse. She asks Angelo to have mercy and let Claudio live. All these notions can be entertained simultaneously. But if Angelo is a tyrant, and Claudio, a mere lover, the plea is meaningless. A tyrant has no mercy and a mere lover does not require one. There is no point of entry. And so Isabella retracts her words with “we speak not what we mean.”

We may care to notice that “we speak not what we mean” leaves ambiguous where the negative sticks. When “we speak no what we mean,” do we say what we do not mean, or do do we not say what we mean? Do our words take on meanings we did not fully intend, when they are released into a discourse, where they gather implications and history we were not fully aware of, or are we just being plain duplicitous? The ambiguous negative coupled with Isabella’s use of the first-person plural implicates Angelo, for he does not say what he means. He occludes his motive in verbiage. And it takes Isabella’s “Let me entreat you speak the former language” for Angelo to say, “Plainly conceive, I love you.” This may be why, Angelo does not reply “Yes, it is” to Isabella’s retraction, for in saying, “we speak not what we mean,” she has not only made a retraction but also an accusation, one that eludes Angelo’s paraphrase.

And it is here, in the implication of Angelo, in the doubling of retraction and accusation, that we might remember the line’s status as a metadiscursive act, one of participation and observation, and entreat it to Berger’s ethical concerns. What is the status of the accusation in relation to the retraction? How are they held together in the plea? Is Isabella responsible for the accusation as much as the retraction? What of her original statement and of Angelo’s paraphrase? How much of the conversation does she effect, and how much does she simply allow to happen? Does her self-conscious speech reflect an effort at self-representation? Does she hear herself, convince herself, that she is a chaste women as well as a good sister, that she has done everything she can for Claudio? Is her plea also an attempt to prepare herself for Claudio’s death after she has declined Angelo’s offer? How do we think about this scene in relation to her soliloquy, Berger’s privileged object of analysis, at the end of the scene?