Architecture!—we started by listening to Alvin Lucier’s “I Am Sitting in a Room,” which is a project in establishing an unmediated relation between room and sound—not sound (say, language) about the room, and not sound in the room, but the room as sound, the particular resonating frequencies of its space abstracted from the voice that activates them. Selena raised some deep questions about conceptual art, whether Lucier’s work could be considered music, alongside traditional projects of, say, writing canons; questions about poetry, music, and work resurfaced (we thought about those with photography). Those who admired the piece responded to the way it challenged the quality of our attention to the patterns of overtones, like standing inside a ringing bell, and how they made us alert to the space (abstracting from it? or perfectly concrete?). Also interesting, though we didn’t talk about it, is what happens to Lucier’s slight stutter, that trace of the recalcitrant body in his controlled language—is the stutter transcended? Effaced? The piece makes for a good way to start thinking about how a poem might engage particular spaces and space in general.

Bachelard let us think about the meanings of home, and the house, as a fundamental site of memory and an original site of safety. We paused to wonder about how this trope functions for anyone whose life did not begin in safety, or even in a home—but even if B. does not describe a universal experience, he may describe a universal fantasy. Quite interesting to think of the formal boundaries of a poem as figuring this basic experience of shelter. The verticality and the condensations of the house—how it stands up out of experience, organizes it, and also collocates meanings and memories—did sound a lot like accounts of what poetry is and does that we have encountered (see Deren and Jakobson on verticality, and Ezra Pound’s idea that poetry is distinguished from ordinary language by its density).

He also explores the analogy between the house and the body, which impressed us in reading Dickinson, another wonderfully oblique lyric that seemed to take the idea of the body as a house for the soul and disembody it—so that the “props” or scaffolding became the physical body, the house itself the soul affirmed. And yet, we wondered if the Christian language—the hints of sacrifice in the language of planks and nails—suggested that the soul’s forgetting of the body is a simple good, or an ingratitude. And then (or actually before, now I’m thinking about it) we thought about Stevens’ wonderful “Anecdote of the Jar,” and its exploration of the jar (is it a house? is it an urn, a poem?) as a kind of colonial architecture. Was it Sam who asked, what is going to happen to this jar/urn/poem—when it is placed in Tennessee, it subdues, even embarrasses the landscape; but what if the poem kept going? Wouldn’t the wilderness have its say, overtake the jar? In understanding the poem, it seems like this organic futurity, this indigenous resilience, is something that it is at pains not to know—but that is part of its meanings, precisely because those pains are taken.

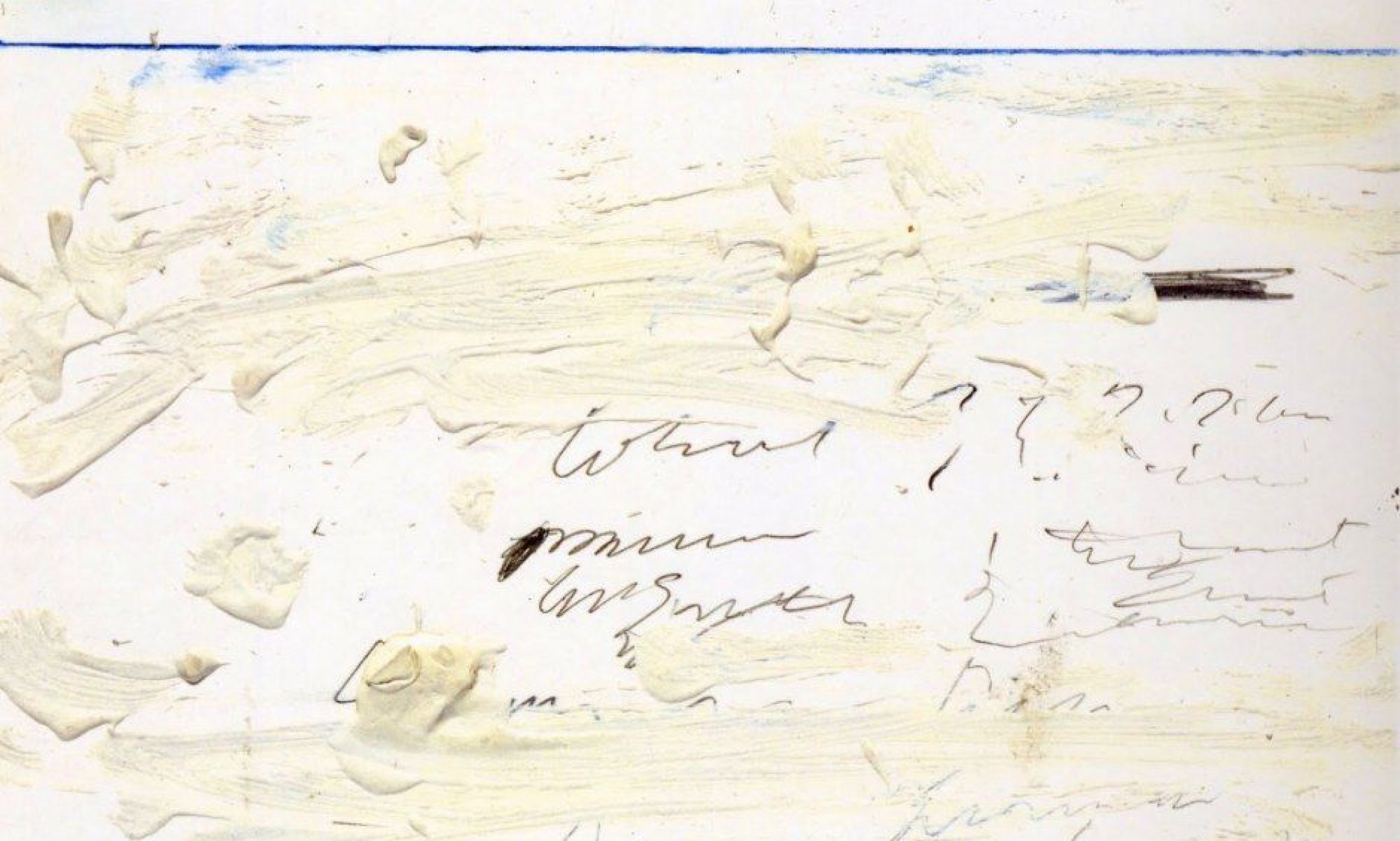

Then Wednesday, Mitch McEwan! I though the meditation on openness was really really provocative—its many meanings, and in particular, how it ought not to be simply identified with modernist transparency (of the glass house variety). Lorde’s poem is worth a re-read, to wrestle with her provocation that the compression, the density of coal is a kind of openness. The instruction to open up a sheet of paper was ingenious and I loved seeing the result. Isn’t a piece of paper already just about the most open thing there is? But no. So many ways to open it (holes, doors, explosions, etc.). Mitch is thinking of the openness of the theater she is working on in Camden, and you could see how Lorde is provoking her to construe that accessibility and invitation in terms other than lots of glass and light—for those modernist tropes now have histories of privilege and exclusion that make them much less easy to enter than they pretend to be. So, what about poems and accessibility? Is a poem that is easy to read the most open? Or is there a greater openness in some forms of difficulty—openness to a wider readership, one that has not been cared for by the forms of openness most widely practiced? I loved ending with a practical exercise like this—do send along your exercises; who knows but they might be built, a poetics of architecture.