I began with a little sermon on the project of definition, as we continue to puzzle out what poetry is in relation to its friends and rivals among the arts. I identified a few basic definitional projects: essentialism (all poems are poems because they share a common essence), family resemblance (poems participate in an overlapping network of shared characteristics), pragmatism (poetry is what we say it is—the word “poem” takes its meaning from how we use it), historicism (we must look to the particulars of use at the moment, and in the place, that concerns us; a variant of pragmatism), subjectivism (poems are poems because of the special effect that they have on us, a variant or at least a cousin of essentialism). I want to keep thinking the relations we pursue this spring, the field of differences, in relation to these definitional possibilities. Also to hold open the question of how the project of defining poetry might be a model for some urgent projects of definition, including contemporary discussions of gender and race; is our basic project an intersectional one?

I then hustled through a summary of ideas we had considered about music, visual art, photography, and performance/drama. We ended up lingering over drama, because John raised some of the discomforts that come with paying attention to life as a performance. We thought about how art in general, and poetry in particular, might offer us shelter from such embarrassments, a free space for the sort of unlimited attention that would be withering if we applied it to another person. The poem is not ashamed under out gaze; therefore we need not be ashamed in gazing, nor interpreting. Which is not to say that a poem cannot be about such interpersonal discomfitures!—and there was an interesting analogy (from Cassy I think and others) to the ways in which drama can forward or occlude its own artifice, advertise its self-consciousness. Does such self-consciousness bring with it questions of shame and of care? What about when a poem owns its identity as a poem?

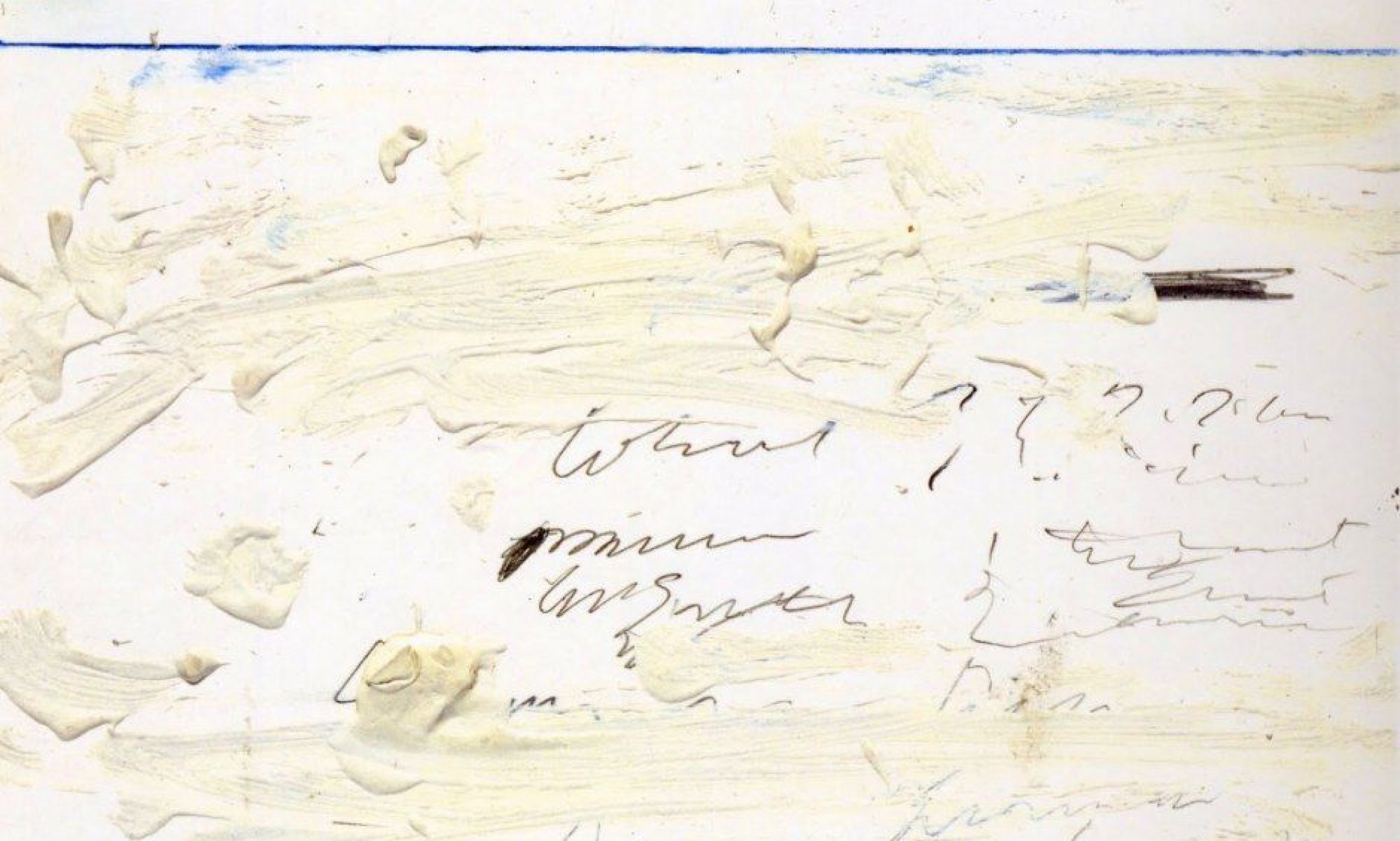

The discussion of Frye on lyric grew very interestingly out of these questions, I thought. Given the arc of the conversation, his account of the inwardness of poetry, between babble and doodle, seemed like a powerful but also vulnerable idealization. What happens when that private poem enters the public world—as it always does? Which poems deflect that publicity, that sociability? Which poems acknowledge it? This will be worth continuing to think about as we turn to dance.

Wednesday, we were on to narrative!—and I thought we did a great job with the three poems that John, Aisha, and Fizzah brought us to, Dickinson, Hong, and O’Hara respectively. It emerged that they were all poems about death, which I had not planned; but death would be, um, a big question for narrative, so it was just as well. Each was in its way evasive of the satisfying structures of succession and transformation that Todorov proposes. It wasn’t clear, as Dickinson moved toward the grave, whether she was passing the sun, or the sun passing her; Hong’s “Our Jim” was a story (as Aisha told it) in which things kept not happening; O’Hara’s day is a loose bag of details until something happens that makes it clear that the only time that matters is the time that stands still. We’ll get to keep thinking about this uneasy argument between lyric and narrative next time.