It was delightful to talk about those cyanotypes, and a few useful distinctions emerged, especially between images that offered pictorial representations of the subject matter (when does a poem ask you to see what it sees?) and those that offered visual metaphors for the poem’s concepts. There was Nicole’s answer back to Stevens, filling up his empty room; John’s choice to figure the same poem’s careless, descriptively indifferent counting (“two or three hills”) with perceptual unclarity (those hazy hills at the bottom of his image). Cammie picked up Komunyakaa’s word “skein” and re-heard it as “skin,” making a surface of matted filigree that transformed the poem’s ideas of ornament. Many other wonderful examples.

We also approached the idea of vantage: interesting to ask, of each of those images, where it stands to look at what it looks at. And of course, what does that term of art, for image, become when we ask it of a poem? Where does a poem stand to look at what it looks at? Give that some thought as you read the Crane assigned for Monday and of course as you make your exercises. Keep in mind, too, that Barthes distinction between stadium and punctum.

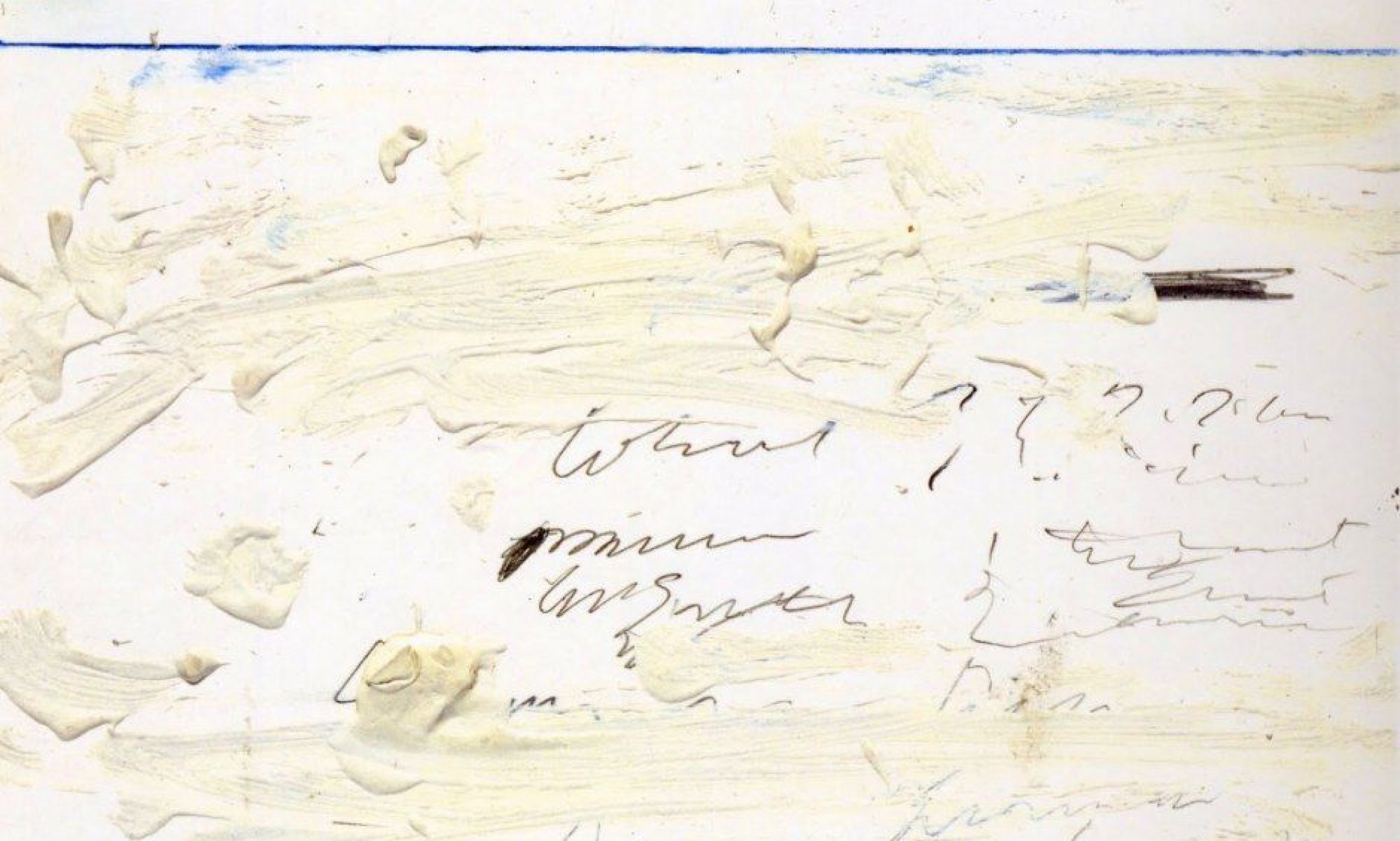

It was a real revelation to me to read Lerner’s “The Voice” together; Selena got us started with questions about the analogy between poem and photograph. On the one hand, the (prose) poem’s relation to time seemed to be so various (Biblical time, the lifespans of generations, the timescales of injustice and of intimacy), the opposite of a snapshot. But those sayings—do they have something of the immediate, world-capturing power of a picture? I thought the line of discussion about the trustworthiness of image and of aphorism was really interesting. The poem really began to open for me, though, when Aveneque brought up that midrash on the lower left margin of the last page: “The ancient rabbis believed lice arose from dust, which is why you can kill them on the sabbath.” Suddenly the long history of the exceptions cultures have made to permit the killing of particular creatures, or people, was in play, the Ukrainian Jews or George Floyd; and connected to those uncanny photographs, by Barbara Bloom—the caterpillar out of place, on the screen door, on the lip of the glass. We could have worked our way even further into the poem’s strange tangle of sympathy and disgust, laws and sayings, history and fakery, tradition and violence…

…but it was good to spend at least a few minutes with Ferry, as he looked at Thomas Eakins’ photograph. Something strange was going on with the poem’s insistence on the photograph’s failure to understand its subject, and the subject’s failure to understand himself. Does the poem understand these failures? Is that all there is to understand? We ended, thanks to John’s question, with a problem of vantage. Is this a poem that inhabits what we have seen of a kind of Platonic skepticism about images, always three removes from the truth? Or is it a poem that dramatizes, that acts out that prejudice, and in so doing affords us an alternative vantage—letting the reader see something of the rivalry of word and image played out in front of us? (Which is to say, the poem may want to establish a vantage for the reader different from the vantage of the poem itself…?)