I began by laying out a few big ideas that may guide us going forward. First, Walter Pater’s claim of the Anders-streben, or other-striving, of the arts, how at their limits they seek the resources of their neighbors. Second, two basic attitudes toward the question: one, a drive toward purity (or medium specificity, as Clement Greenberg put it), the idea that each art most fully realizes its nature when it pursues what only it can do; two, the belief that hybridity and or interdisciplinarity spurs artistic discovery, and that the arts renew themselves in contact with other arts (or discourses, disciplines, etc.). And third, the important role that metaphor will play in these negotiations, specifically how terms that are literal in one art become figurative in another (e.g. foreground and background, literal in painting, figurative in poetry—and then one asks, figurative for what?)

I also launched us on the question of definition more generally. If poetry has long been defined by attempts to defend it (Sidney and Shelley both wrote essays entitled “A Defense of Poetry,” and many more might bear the name), our project is one of affinities and differences. Encounters with the other arts may tempt us with the idea that we have discovered poetry’s essence (e.g. Horace’s ut pictura poesis, as painting, poetry). But we will bear in mind Nietzsche’s reminder that “nothing with a history can be defined,” and though he won’t arrest our definitional curiosities, he will remind us that workable definitions may shift, from occasion to occasion and relation to relation. Poems may have their own implicit accounts of what makes them poems.

Next, after some class business, we tool a random walk through a few samples of poetry, with the question, what is it about this text, image, etc., that makes it poetical? Everything that came up is fair game as we go forward: even the most basic questions like, why are so many poems short? We will have the privilege, in this class, of exploring them from from a variety of perspectives, e.g., short compared to a novel, or to a song; or to a painting (is a painting “short” compared to a novel? or is it instantaneous? what governs its temporality, anyhow, and how does it related to the time a poem represents and/or takes?). Just a few of the questions that came up:

- Line and stanza. We’ll want to think about line, especially, how it is and isn’t like a visual line. How do lines interact with sentences?

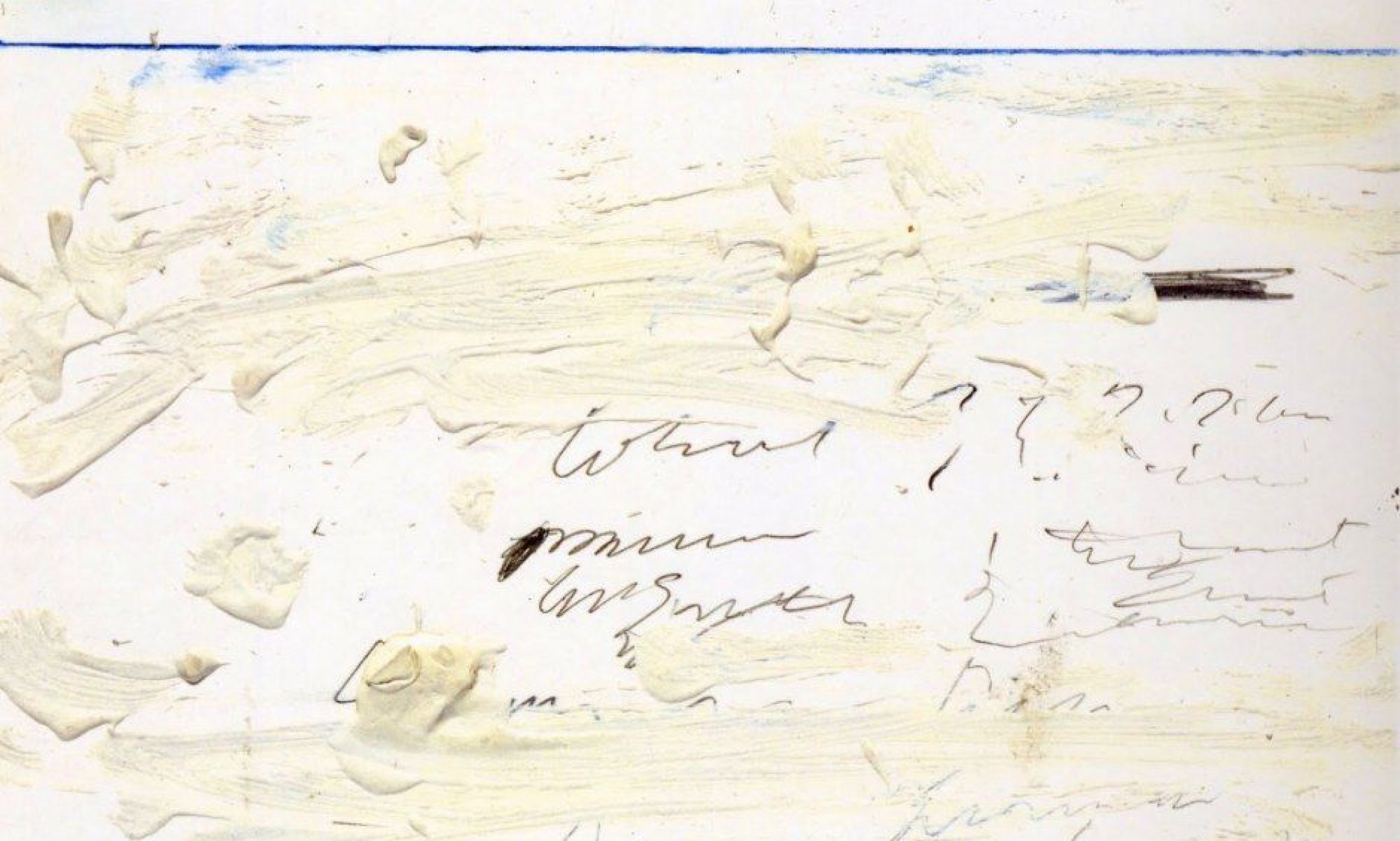

- Shape: a ragged right-hand margin is a giveaway, but other shapes (like the step-structure of Schwitter’s Ursonate) also point us toward the hypothesis that a text is to be read as a poem.

- Rhythm: a poem may have a special organization of rhythm; how does this interact with the complex term voice (as the medium of most poetic performance, and also as a word for the distinctive sound of a poet, even on the page)?

- Imagery and metaphor. To identify an image in a poem is to translate ourselves into a visual language: what does the term mean, when it is used of words? Is it the same as metaphor, or how are they related? (What is metaphor, anyway, and how do you recognize it?)

- How is it that a certain speculative or (as Cammie put it) philosophical quality might incline us to read a text as a poem? What kinds of conceptual challenges or difficulties or adventures are native to poetry? And what do they have to do with difficulty, and the call for interpretation?

- We thought about the deliberateness of a poem, the sense that it is uncommonly determined, chosen; that no word can be altered without making a new poem (a familiar definition of poetry: as opposed to prose, much more amenable to paraphrase). How to square that with the sense that poetry can also give us language that is unusually mobile, candid about its process or even in the middle of it?

- And a high degree of rhetorical patterning, e.g. Whitman’s anaphora (“You shall…you shall” etc.). Does this call us to poetic reading? If so, how differently than (for example) public oratory?

As I have phrased some of these observations, perhaps the question is, what has to happen in a given text not so much for it to be a poem, as for us to read it as one—what does language have to do to solicit such attention from us? And what is poetic attention, anyhow?