GABRIELE MÜNTER PHOTOGRAPHER OF AMERICA 1898-1900

by Lionel Gossman (Department of French and Italian, Princeton University, emeritus). ©2017.

This essay has been altered slightly from the print edition for the web.

A Limited Reputation in the U.S.

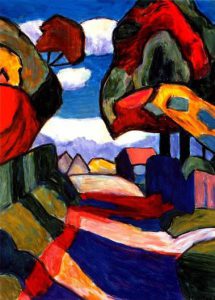

One of the founding members in 1911 of the much admired avant-garde artists’ group known as “Der Blaue Reiter” [The Blue Rider], Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) is much less well known in the U.S. or Great Britain than in her native Germany, where her work has been shown in private galleries since 1909 and well over 50 exhibitions have been devoted to it in major public galleries, the latest being scheduled to open at the Lenbachhaus in Munich on October 31, 2017 and to run for five months. The first showing of Münter’s work in the U.S., in contrast, did not take place until 1955, at the private Curt Valentin gallery in New York. Four other shows in private galleries in New York and Los Angeles followed in the 1960s. 1 It was 1980 before the first exhibition of Münter’s paintings and drawings in a public gallery — curated by the University of Massachusetts art historian Anne Mochon — opened at Harvard University’s Busch- Reisinger Museum. This exhibition was also seen at the Princeton University Art Museum the following year. In the late 1990s a retrospective exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum — this one curated by University of Chicago art historian Reinhold Heller– traveled to Columbus, Ohio, Richmond, Virginia, and the McNay Museum in San Antonio, Texas (1997-98), and in 2005 Shulamith Behr of the Courtauld Institute and Annegret Hoberg of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich curated an exhibition at the Courtauld Institute Gallery in London, about which the critic of the Independent on Sunday newspaper wrote: “This small jewel-like exhibition is in its quiet, unobtrusive way one of the best shows in London.”2

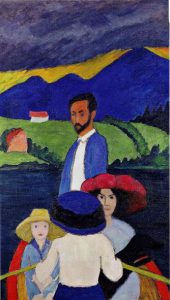

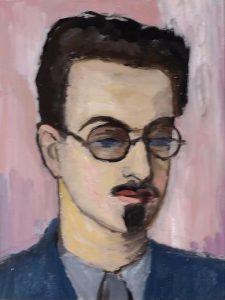

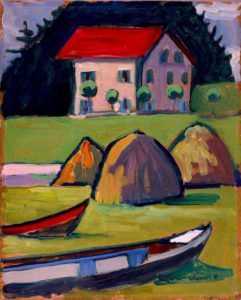

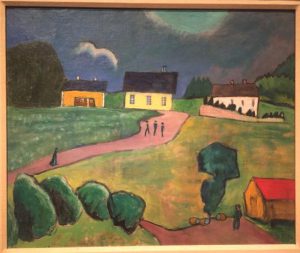

The impact of these relatively rare displays of Münter’s art seems to have been not very considerable. Münter is still far from widely known or appreciated in this country and a comment in the student Harvard Crimson at the time of the Busch-Reisinger show is still valid in large measure: “A worthy but obscure artist͘ […] Persuading friends to visit an exhibition of an artist as little-known as Gabriele Münter may be difficult, but it is well worth the trouble. Few are familiar with Münter’s work; that’s a shame.” 3 Other founding members of the Blue Rider have been similarly neglected in the U.S., notably August Macke (1887-1914), Alexei Jawlensky (1864-1941), and to a lesser degree Franz Marc (1880-1916) — all three outshone by the group’s groundbreaking initiator Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Münter’s teacher, collaborator, and lover for over a decade, from 1903 until World War I (figs. 1-6) when, as an enemy alien, he had to leave Germany and return to his native Russia. 4

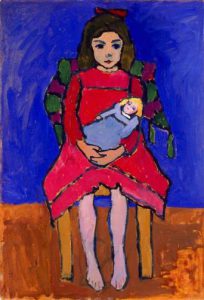

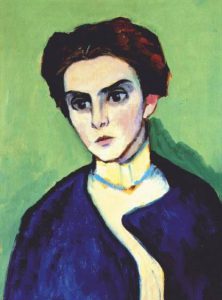

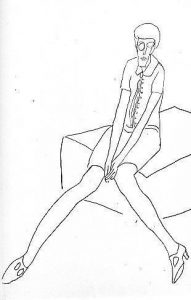

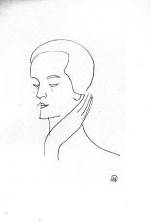

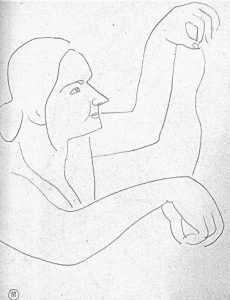

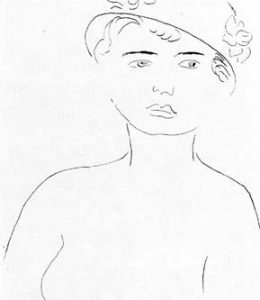

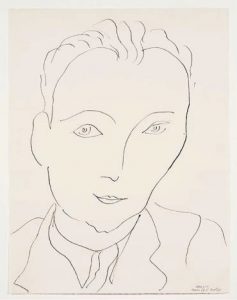

Albeit a gifted and productive painter in her own right, with a special talent for line drawing that has been compared to that of Matisse 5 (figs. 7-15), Münter was overshadowed during her lifetime — and inevitably still is, even in Germany, despite having finally won broad recognition there, especially since the late 1940s — by her extraordinarily gifted teacher and lover.

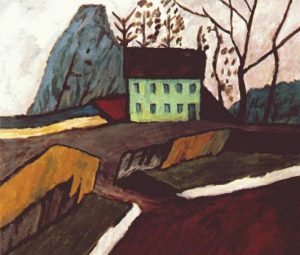

As she herself noted in her diary (October 27, 1926) with some bitterness, a decade after Kandinsky effectively broke off their relationship, “In the eyes of many, I was only an unnecessary side-dish to Kandinsky. It is all too easily forgotten that a woman can be a creative artist with a real, original talent of her own. A woman standing alone [. . .] can never gain recognition through her own efforts. Other ‘authorities’ have to stand up for her.”6 Given, in addition, the almost exclusive focus of British and American collectors on Paris, it is not surprising that there are few works by Münter in U.S. galleries and museums. Princeton’s Art Museum is unusual in having six of her paintings, all donated by the family of Frank E. Taplin (Princeton class of 1937). (Figs. 16-21)

Otherwise, with the notable exceptions of the Milwaukee Art Museum, which has fourteen works by Münter, and the San Diego Museum of Art, to which six of her paintings were donated in 2011 (figs. 22-28), only seven U.S. galleries (Art Institute, Chicago; Cleveland Museum; Guggenheim, MOMA, and Neue Galerie in New York; National Gallery and National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.), have even a single work by her. In all the public collections in Great Britain, there is one painting by Münter — at the New Walk Gallery and Museum in Leicester. The first Münter painting in any French museum was acquired by the Centre Pompidou in 2015!

It is hardly to be wondered at, therefore, that there is almost no awareness in the U.S. of Gabriele Münter’s American connection or, in particular, of the hundreds of photographs she took in Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas in 1898-1900. 7 These photographs — amounting to about 400, of which a generous selection was published in 2006-7, at the time of a major exhibition at the Lenbachhaus in Munich (September 2006 – January 2007) curated by the eminent scholars of modern German art Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel, then director of the Lenbachhaus 8 — are the focus of the present short study. 9 While it is hoped that they may also stimulate interest in Münter as a painter, they are primarily directed here toward students of American history and the history of photography. For this reason some comparable works by contemporaries of Münter’s, among them the still rather neglected Evelyn Cameron, a British woman who settled in Montana in 1889, have been included in the following image portfolios (figs. 119, 124-125, 132- 134). (see appendix). 10

![[Early version of] Kandinsky and Erma Bossi at the tea-table. c. 1910.](https://commons.princeton.edu/munter/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2018/02/figure19-300x211.jpg)

![Kahl [Barren landscape] 1947.](https://commons.princeton.edu/munter/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2018/02/figure21-300x263.jpg)