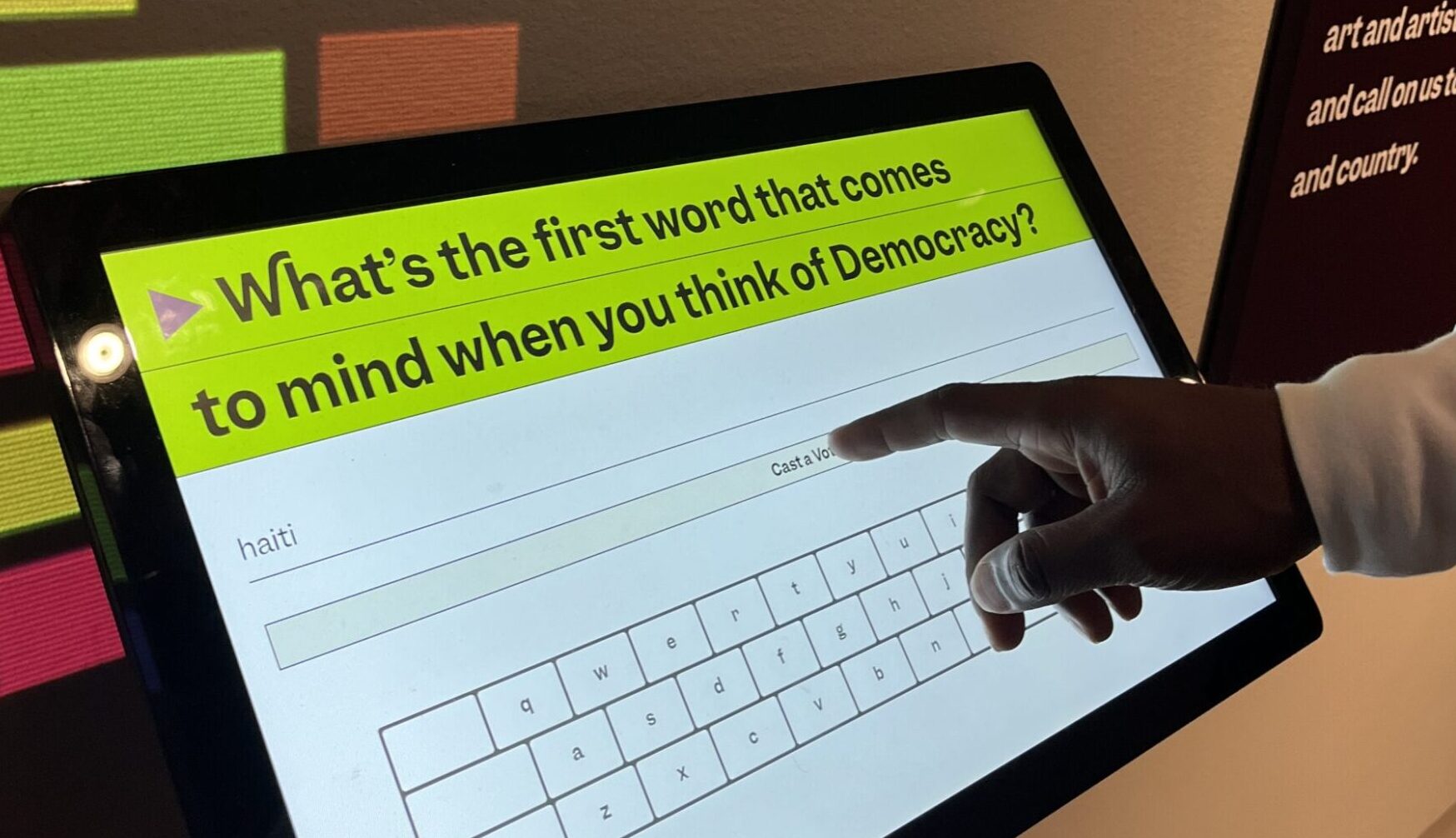

On a recent visit to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston my family and I found something a bit unsettling in the exhibit “Power of the People: Art and Democracy” : an interactive piece that created a mind map,collaging words visitors associated with “democracy.” Included in were words ranging from names of politicians and philosophers, to adjectives of both positive and negative connotations, to countries of origin. Naturally, we wanted to participate in the collective art-making so I typed “Haiti,” and despite several variations was met with the same response: “please try a different word.” Knowing the history of our country, it was unbelievable that it could be excluded from any conversation on “democracy.”

While this damper in our visit may seem inconsequential, it reflects a wider phenomenon of the social and political ‘othering’ of Haitians both in the country and in diaspora. Haiti has always been haunted by the way it’s represented through the Western gaze. Every time Haiti comes into the news or cultural purview abroad, it’s in light of the most recent disaster. Consider the 2010 earthquake, its longstanding title as the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere, gang activities, government corruption, and international intervention, borders to migration and social isolation: Haiti is always depicted as the locus of several disasters. Whether it’s environmental, economic, political or social disaster, all of these issues are crises that, because of colonially cemented power imbalances have been exacerbated, and because of the erasure of the underlying causes of these disasters, Haiti and its alterity are consistently sensationalized. Through this framework, I propose that the majority (or at least most visible) media and pop cultural portrayals of Haiti work to first conceive of Haiti as a disaster state and then to inscribe that disaster onto Haitians in Haiti and the diaspora.

Haiti and its ‘Disastropolitans’

To even begin to address the media disaster that has befallen Haiti and its people, one must first understand what constitutes a disaster. In the context of post–hurricane María Puerto Rico, political anthropologist Yarimar Bonilla writes about the coloniality of disaster emphasizing “the ‘slow violence’ of colonial and racial governance which sets the stage for the accelerated dispossession made evident in a state of emergency”(Bonilla 2). Here, disaster is not characterized by any sort of extraordinary, unforeseeable, or natural hazard or event, but is largely determined by the violent forces associated with colonialism and neo-colonial exploitation or other cultural violences with roots in those same atrocities. Though disaster is often associated with “natural disasters” like earthquakes and hurricanes, these are neither the root cause of disastrous circumstances nor are they the only types of disasters that follow Haitians (though the 2010 earthquake and its aftermath has significantly marked the way Haiti and Haitians are perceived). Haiti is construed as a locus of disasters, especially in the context of the Americas. This can be attributed to what one could call the original disaster of colonialism. When the violence of colonialism was inflicted on Haitians, they fought for and in 1804 gained their independence as the first independent Black nation in the world and in the same moment they became symbols of Black sovereignty and the event which “radically upend[ed] the basic premise of white supremacy…transform[ing] global conception of freedom” cemented the nation as “the physical manifestation of white people’s deepest fear” (Alexander 5). This has only been exacerbated by the recent events that constitute political disaster, and have led to large scale migration from Haiti.

Because of the compounding disasters in Haiti, the already large diaspora has grown with immigration mainly to the United States, the Dominican Republic, Chile and the Bahamas.

This reveals an important aspect of the Haitian condition: Haitians are as marked by disaster as Haiti. For example, Gina Ulysse in Why Haiti Needs New Narratives laments the “fragmentation” and “dehumanization” of Haitians, particularly in media portrayals that either use “subhumanity” to posit Haitians as “irrational-devil-worshippingprogress-resistant-uneducated-accursed-black-natives overpopulating this godforsaken land” or “superhuman[ity]” to describe Haitian resilience (10). Haitians are reduced to the positions disaster forces them into and stripped of their personhood because of it. However, in the media, this association of Haitians with disasters extends beyond any logical or direct connection to disaster. Haitians migrating to other places in the Americas have been criticized and dehumanized in a variety of contexts from the large-scale deportations announced and carried out by Dominican President Abinader to the U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s violent, baseless, yet continuous remarks against Haitians. However, the issue of negative representations of Haitians goes beyond the dehumanization that is weaponized against migrants everywhere. Haitians are so marked by otherness, that even in contexts where there’s no link to migration or political status Haiti and Haitians are simultaneously evoked as bad examples. Take a recent New York Times article with the headline “A Power Vacuum in Gaza Could Empower Warlords and Gangs” the only common thread between the subject of the article and Haiti is the broad idea of gangs which exist everywhere.

This perpetual attribution of violence and disaster onto not only Haiti but Haitians is reflective of “locating vulnerability within geographies, neighborhoods, social identities, or even bodies [thus] render[ing] those [same localities] as ‘weak’ or ‘risky’” (Marino and Faas). This reduces Haiti into a disaster state and turns all Haitians everywhere into what I call disastropolitans.

Current Imagery

Upon a simple Google search of Haiti there are copious images that either completely collapse the complexity of Haiti into the pornographic depiction of poverty and violence or trade it in for fetishized wallpaper-like images of nondescript beaches.

However, even in media portrayals the images that circulate most depict Haitians through desperation and or resilience. To illustrate this point, some of the photos of Haitian immigrants that received the most attention in the past few years are from 2021 with Haitians crossing the Rio Grande River under extremely dangerous conditions. While these images are incredibly important as they display the lived realities of Haitians, when these are the only types of images of Haitians on the cultural landscape, it reduces them to the position of disastropolitan which then takes away from other aspects of their lives and experiences.

(Post) Disaster Artists and Hopeful Pessimism

Now that we have established the issue of not simply a lack of representation of Haitians in the media and popular culture, but a reductive misrepresentation of them as nothing more than disastropolitans, the question becomes how can this be remedied?

One solution, considering this as an issue of vision and imagery, is to turn to the arts. The arts offer an avenue through which Haiti, Haitians, and their personhood, desires, interests, etc can be explored beyond the exploitative and often non-critical lens of disaster. What’s more interesting is that Haiti and Haitians themselves have already been generating new images to craft new narratives. Speaking from the contemporary art world, artists have been on the art scene both in Haiti and abroad from decades reimagining what Haiti and Haitians and their experiences can and does look like. As a painter and sculptor, Edouard Duval-Carrié uses his work to anticipate and materialize futurity for Haitians in which they are allowed to be more than “poor,” “desperate,” or “resilient” migrants. For example, in a series of paintings called Imagined Landscapes Duval-Carrié uses imagery that could simultaneously romanticize the landscape in a way that has been done in the colonial past, and re-envision what it should still and perhaps can again look like for Haitians. He also employs the images of spirit-like figures showing an ambiguity with who is inhabiting the land, drawing on spiritual and perhaps ancestral imagery to reckon with the ways colonialism and neocolonialism have battled with traditional aesthetics.

Another contemporary artist is Steven Baboun who uses photography and his co-founded creative studio to not only actively create new images for Haitian immigrants and diasporans, but to work with others to co-create these narratives. Baboun has photographed other Haitian artists and creatives but also families managing to capture them in new and more dignified lights.

This is not even to mention the rich art scene in Haiti, that continues to thrive even in the midst of disaster. It seems that if nothing else, perhaps even the only one, the “disaster state” of Haiti hasn’t experienced a creative disaster.

Beyond the poetics of representation there are real impacts for the socio-political trajectory of the country. Dr. Bonilla’s framework of hopeful pessimism, that is, an acute awareness of “the hard tasks required to transform the here and now” which can motivate efforts to “build politically in the face of ruin and the promise of further decay” seems helpful here (157). It’s useful in re-examining the role of pop cultural representations of Haiti and Haitians because fully responding to Haiti’s disasters will take time (the disaster state isn’t rebuilt in a day). However, this doesn’t mean nothing can be done to improve the reality of Haitians today, and any positive attention and alternative narration brings Haitians closer to more wholly legible personhood beyond the disastropolitans they are made to be.

Works Cited

Alexander, Leslie M. Fear of a Black Republic : Haiti and the Birth of Black Internationalism In the United States. First edition. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Bonilla, Yarimar (2020) “The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA” Political Geography Vol 78

Marino, Elizabeth K., and A.j. Faas. 2020. “Is Vulnerability an Outdated Concept? After Subjects and Spaces.” Annals of Anthropological Practice 44 (1): 33–46.

Taub, Amanda. “A Power Vacuum in Gaza Could Empower Warlords and Gangs.” The New York Times, 1 December 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/01/world/middleeast/a-power-vacuum-in-gaza-could-empower-warlords-and-gangs.html?searchResultPosition=1. Accessed 14 December 2024.

Ulysse, Gina Athena. Why Haiti Needs New Narratives : A Post-Quake Chronicle, Wesleyan University Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/princeton/detail.action?docID=1844186.