In a recent journal publication, sociologist Yarimar Bonilla argues for local or personal resilience as a method of combating colonial exploitation that has led to issues like inadequate infrastructure. Supporting a revolutionary idea to drop the old method of life–which looked to the state for support–and adopt a new lifestyle which seeks to unionize communities to become self-dependent and wait no longer for government intervention. This is seen when activists are seen creating demonstrations within their own communities to inspire local mobilization instead of voicing their demands at government agencies. Or, in the context of the energy crisis, citizens create their own forms of solutions through the sourcing of back-up generators, solar energy, etc.

All the while, another scholar on the topic, Roberto Barrios, argues that this kind of resilience can have a polarizing effect which leads to further abandonment and continued disaster capitalism. He rather promotes the idea that resilience is built and maintained by the government. In this view, the same autocratic powers that force communities to become resilient must be the ones relieving this burden as they have the power to “reverse” decisions. In effect, removing stigmas that have created false narratives of a resilient Puerto Rican who can overcome any disaster because at some point natural disasters can become too strong for the most resilient, making it a social disaster instead. However, this cannot be accomplished without state attention to local affairs or grassroot movements which highlight the struggles and areas of improvement, thus enabling the government to make an informed decision.

In order to put an end to this type of exploiting, the energy transition in Puerto Rico requires the removal of economic and political backing in decision making. The problem in Puerto Rico is not energy generation, it is the centralization or privatization that doesn’t allow the island to recover and distribute energy accordingly after a disaster; hence the need for reliable microgrids that run on renewable energy. One which is developed without political or capitalist support but rather focused on uplifting, not maintaining, the socio-economic status of Puerto Rico. One which is based on heavy civic engagement rather than top down approaches to the energy crises. And finally, a grid which is researched and backed by science to take advantage of the recent advances in renewable energy technologies.(Energy Policies in Puerto Rico…, O’Neill-Carillo)

For example, groups like Queremos Sol Coalition and the Interstate Renewable Energy Council are currently working to implement microgrids.(Puerto will not go… , Bonilla) Microgrids allow for communities to generate solar energy in the day and store it for the night based on the community’s own demand.(A former Marine’s… , Ennis) A solution backed by science as solar panels take advantage of the plentiful insolation (light energy per unit area) that Puerto Rico receives.(Energy Policies in Puerto Rico…, O’Neill-Carillo) Overall, microgrids shape resilience to disaster as the energy sector is diversified and customized through this patchwork technique.

It is these types of solutions and civic engagement that the commonwealth should be involved in if it seeks to begin the road to whole country resilience and autogestion in all sectors, not just energy. As the country continues to deal with the lack of paved roads and reliable transportation systems, issues with accessible drinking water or food sovereignty, collapsing homes and schools, and many more social disasters which are only exacerbated in the presence of a hurricane; solutions that begin on the ground but are ultimately led and powered by the government, will become pertinent to creating sustainable infrastructure in Puerto Rico. Solutions which are socially, ecologically, and economically sustainable. Successfully, reversing the chain of decisions that were once fueled by profit, but are now fueled by the well being of the people, especially during times of crises and uncertainty. Which in turn removes the burden of reliance and auto-gestion that was previously forced upon individuals but is now backed by a whole country and its government.

- Acevedo, N. (2024, June 14). Puerto Ricans struggle to grasp economic impact of recurrent power outages. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-power-outages-economic-impact-rcna157094

- Acevedo, N., & Reuters. (2018, July 11). U.S. plans to remove backup power generators in Puerto Rico. officials worry it’s hurricane season. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/puerto-rico-crisis/u-s-plans-remove-backup-power-generators-puerto-rico-officials-n890526

- Advancing Clean Energy in Puerto Rico. Earthjustice. (2023, May 1). https://earthjustice.org/case/advancing-clean-energy-in-puerto-rico

- Antonetty, A. D. R. (2023). Historicizing puerto rico’s energy present: A political ecology and environmental justice approach to energy production in puerto rico. Centro Journal, 35(1), 57-80. Retrieved from https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/historicizing-puerto-ricos-energy-present/docview/2826827359/se-2

- Barriors, R.E. (2016), Resilience: A commentary from the vantage point of anthropology. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 40: 28-38. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12085

- Bonilla Y, The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA, Political Geography, Volume 78, 2020, 102181, ISSN 0962-6298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102181.

- Bonilla, Y. (2024, June 23). Puerto Rico will not go quietly into the dark. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/23/opinion/puerto-rico-luma-blackout.html

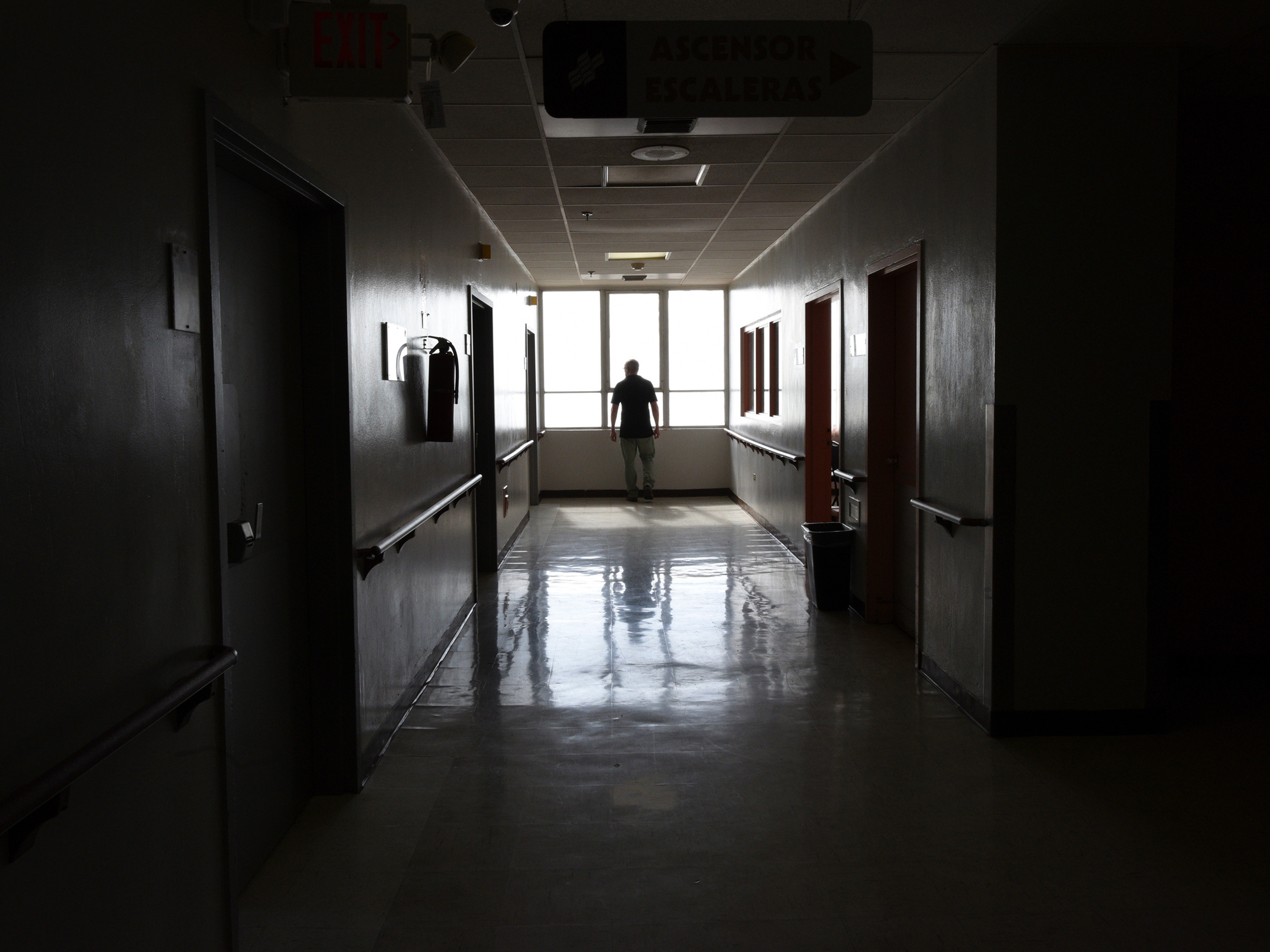

- Burnett, J. (2017, October 5). 112 degrees with no water: Puerto Rican hospitals battle life and death daily. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/10/05/555796327/following-disaster-teams-in-puerto-rico

- Declet-Barreto, J., Middleton, Z., Ekwurzel, B., & Cleetus, R. (2023, August 24). Puerto Rico deserves full benefits of Biden’s justice40. The Equation. https://blog.ucsusa.org/juan-declet-barreto/puerto-rico-deserves-full-benefits-of-bidens-justice40/

- Ennis, B. (2023, August 14). A former Marine’s crusade to bring renewable energy to Puerto Rican communities ” Yale climate connections. Yale Climate Connections. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/08/a-former-marines-crusade-to-bring-renewable-energy-to-puerto-rican communities/#:~:text=Forty%2Dthree%20percent%20of%20Puerto,%2C%20which%20is%20about%203%25

- O’Neill-Carrillo, E., & Rivera-Quiñones, M.,A. (2018). Energy Policies in Puerto Rico and their Impact on the Likelihood of a Resilient and Sustainable Electric Power Infrastructure. Centro Journal, 30(3), 147-171. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/energy-policies-puerto-rico-their-impact-on/docview/2196367165/se-2

- U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – independent statistics and analysis. EIA. (2024, February 15). https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=RQ

- Yaffe-bellany, D., & Pérez, L. N. (2024, August 13). The unraveling of a crypto dream. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/13/technology/brock-pierce-crypto-puerto-rico.html?ogrp=dpl&unlocked_article_code=1.TE4.InjY.XMxKjdlS12Lt&smid=url-share