As written in Politico, there is an exception to the 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery: involuntary servitude can still be used as punishment for crime, creating the foundation for our modern prison labor system (Schultheis 2024). In California, Proposition 6, which sought to end forced labor as punishment, failed by a narrow 5% margin. This raises critical questions: What went wrong, and where do we go from here?

This essay will illuminate systemic injustices within prisons, highlighting how they profit from forced labor. I will use the framework of disaster studies to understand how marginalized and oppressed populations experience exacerbated outcomes that maintain disaster status because of a lack of adequate supportive infrastructures and institutional negligence. Then, I will explore the barriers that led to the failure of Proposition 6. Finally, I will propose pathways forward through resistance and disruption, advocating for a future that dismantles contemporary systems of oppression.

Systemic Injustices Create Social Disasters

Contemporary Slavery in Prisons

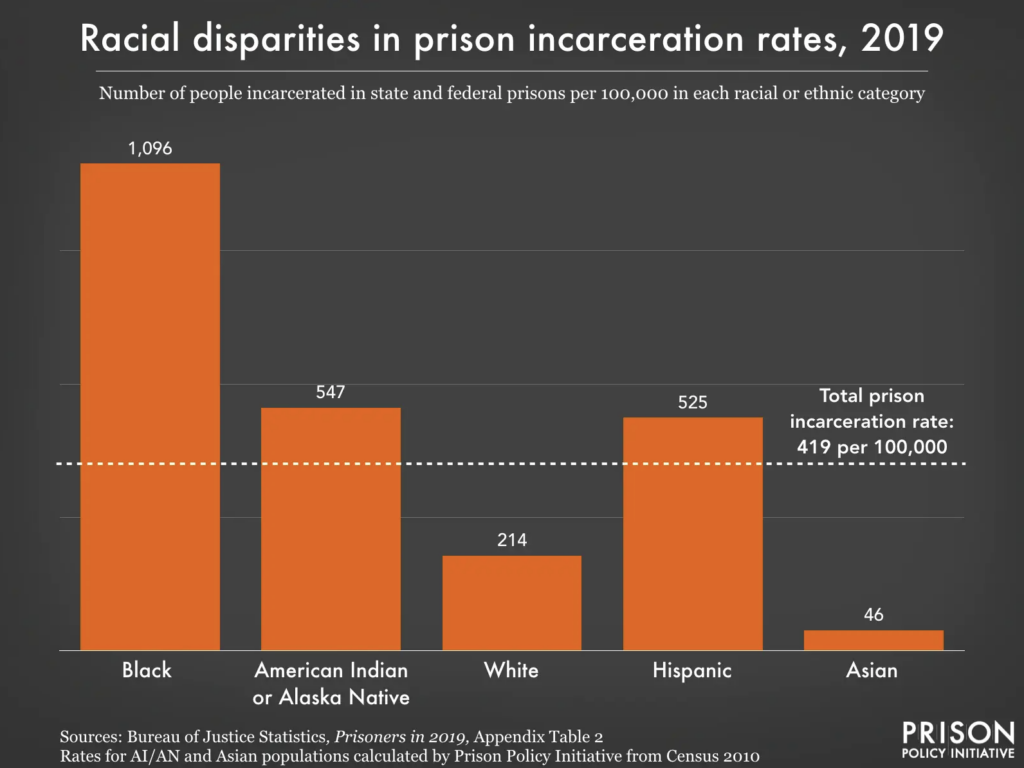

In critically analyzing prisons, we must recognize the centuries of success these institutions have had in oppressing marginalized populations. The Jim Crow era exemplifies how racial identity has historically been criminalized. Michelle Alexander articulates this clearly in The New Jim Crow, explaining how incarceration perpetuates contemporary forms of enslavement for BIPOC people (Alexander 2020). Today, we see this cycle continue with undeniable racial targeting by police, unfair trials, and disproportionate prison sentencing (Wiley 2022). See Figure 1.

In the 1980s, at the start of mass incarceration, as we see it today, privatization and corporate growth boomed under Ronald Reagan, with corporations contracting labor from prisons at extraordinarily low rates. This exemplifies disaster capitalism, as theorized by anthropologist Dr. Yarimar Bonilla (Bonilla 2020). Disaster capitalism explains how the history of colonialism, racism, and empires has created and sustained structural inequality, making people vulnerable to exploitation. Empires perpetuate these systems by parentifying marginalized communities, creating a narrative of salvation while profiting from systemic interventions. Forced labor within mass incarceration exemplifies this dynamic, as corporations exploit populations continuously made vulnerable and neglected.

The use of forced labor in prisons remains one of the most egregious aspects of this system. Punishment takes precedence over care, reinforcing the societal obsession with retribution. If we consider how the colonial history of America has constructed minority populations as threats, then President-elect Trump’s plans for mass deportation should be alarming. He capitalized on the perceived threat of minority populations to justify their subjugation. Furthermore, there is the risk of labor insecurities, but the U.S. has historically replaced exploited populations with other groups as sociopolitical circumstances have shifted, as seen with Japanese internment and the Mexican Braceros Program (Loza 2017). What is to stop the government from employing imprisoned populations to replace deported workers?

Privatization, Profit, and Forced Labor

Forced labor within prisons does not rehabilitate but rather perpetuates systemic harm. Private companies profit from these labor practices, creating incentives for mass incarceration. While opportunities are often advertised as “skill-building,” the wages are negligible, and incarcerated individuals often have no choice but to work. This directly ties into the prison’s capital gains while failing to provide genuine opportunities for rehabilitation (Sawyer 2017). These exploitative practices regress into modern-day slavery and require immediate scrutiny.

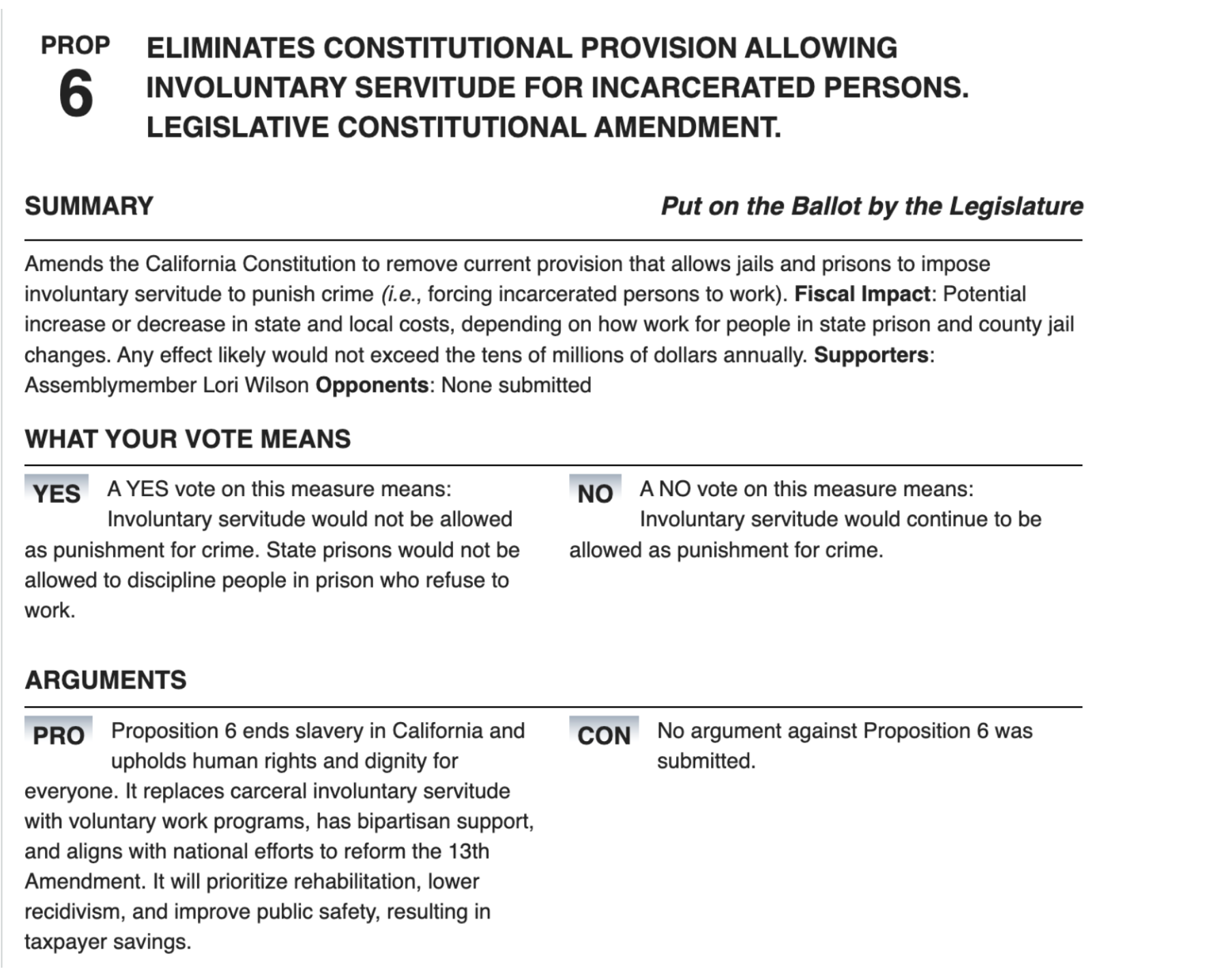

In advocating for Proposition 6 and similar legal amendments in other states, formerly and currently incarcerated people have been the greatest advocates for this change by testifying to the hindrance of their rehabilitation because of their forced labor. Steve Brooks is an award-winning journalist incarcerated at San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. After the election, Brooks wrote an article for Time magazine: I’m Incarcerated in California. Here’s What Prop 6 Not Passing means for People Like Me (Brooks 2024). He shares that he thinks Proposition 6 largely failed because of the message it sent voters; “many voters believed its focus was about incarcerated people choosing not to work altogether–rather than having the right to choose where and how we worked,” (Brooks 2024). Additionally, the complex language of Proposition 6 likely alienated voters with lower literacy levels or fewer educational resources, creating an accessibility barrier. Studies have shown that many propositions are written above the average reading level of voters, complicating their ability to understand critical policy changes. See figure 2 for ballot language.

Notes: Proposition 6, as seen on voter guide materials and as included on the ballot. Notice that the opposition to propisition did not include an argument against Proposition 6.

ABC 10, a local California news station, also reported on the failure of the proposition in comparison to Nevada’s successful initiative. Esteban Nuñez with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition reports that Nevada’s largest difference was the inclusion of “slavery” in the ballot title summary, instead of California’s “forced labor.” The following testimony captures other sentiments brought on by forced labor advocates who are currently incarcerated:

“We are saving [the prisons] millions of dollars and getting paid pennies in return or an extra piece of meat. All the jobs we are doing in prison are not really benefiting us; it is more benefitting the prison system. I work a job making $450 for a whole year. If they were to pay a civilian for the same job, that would be his pay for just one week.” – Latashia Millender, incarcerated at Centralia Correctional Center, IL; Quote excerpted from the ACLU’s report on captive labor (Turner 2022).

Incarcerated people do not have basic labor protections because courts have decided incarcerated people are “wards”, thus not qualifying for employee benefits (Turner 2022:58). Other reporting on prison labor in recent years has brought attention to the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) incarcerated people are given for their protection when working with dangerous or hazardous materials. The COVID pandemic also brought a wave of such exploitation of incarcerated people by having them fill in undesirable jobs or non-essential labor that could still be done under loosened safety restrictions. For example, several people tested positive for COVID after working on a farm in Arizona, and others were working with bodies in mobile morgues or biohazardous materials (Anderson 2020; Turner 2022). See Figures 3 and 4.

Moving Forward: Resistance and Disruption

Advocating for Change with Hopeful Pessimism

Dr. Yarimar Bonilla’s concept of hopeful pessimism provides a framework for addressing systemic issues like mass incarceration and forced labor. Hopeful pessimism acknowledges the pervasive nature of inequality and systemic harm while encouraging the pursuit of transformative change. Bonilla’s work highlights how communities must resist abandonment by oppressive systems and confront the habitual disillusionment caused by structural inequality (Bonilla 2020). Instead of relying on government intervention, individuals and communities must reckon with their complicity and actively engage in dismantling these systems of oppression.

In a time when a family is one misfortune from living on the streets and becoming subjected to further scrutiny and punishment instead of aid, we must question why we continue to subject ourselves to this system. By remaining ignorant of the status of the world beyond our immediate surroundings, we lose sight of the end goals. Ending mass incarceration and improving the rights of incarcerated people while working toward abolition are essential goals that need immediate attention.

Reimagining a Just Future

Ultimately, our goal must extend beyond passing legislation like Proposition 6. We must reimagine systems of justice that center rehabilitation, equity, and care. The exploitation of incarcerated individuals underlines a broader societal failure, and dismantling these systems requires both resistance and radical imagination.

In Brooks’ testimony of support for Proposition 6, he shares the sentiments he heard in his research, such as a “lack of faith in our criminal legal system,” but this lack of faith leads to people ignoring prevalent social issues if they are not directly impacted by them (Brooks 2024).

Looking toward our next election, advocates will continue to push for this proposition, according to ABC 10, and they provided a statement from the Attorney General’s office as to how they decide on the language on the ballot (Nguyen 2024). If we choose to continue the work of bureaucratically made changes, we should consider the pressure we place on people who have the greatest influence, such as the Attorney General. In the education of voters in general, it should be noted how influential our political representatives are, so we should also be aware of who we are voting into powerful positions such as the attorney general.

There should also continue to be a call for corporate accountability. Similar to disaster capitalism in Puerto Rico, the prison industrial complex allows corporations to exploit workers, receive large tax breaks, and subjugate incarcerated people (Pfaelzer 2023:331). People who are incarcerated are dehumanized and made disposable by corporations while using hostile tactics such as creating illusive benefits to work like early parole. However, there is no accountability for corporations and prisons to prove that people who work are compensated and have a safe, non-exploitative work environment.

CONCLUSION

The failure of Proposition 6 underscores the systemic barriers to addressing modern slavery in prisons. Incarceration disproportionately harms families and communities, perpetuating cycles of poverty and criminalization. While bureaucratic methods have limitations, we can harness this moment to build broader awareness and advocacy. By addressing accessibility, fostering community engagement, and embracing hopeful pessimism, we can envision a future free from the remnants of colonial exploitation.

REFERENCES

Pfaelzer, Jean. 2023. California, a Slave State. 1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sawyer, Wendy. 2017. “How Much Do Incarcerated People Earn in Each State?” Prison Policy Initiative.