“Dirty”, “underground”, and a “triggering factor for criminal acts”, were among the various descriptions assigned to one of the most popular genres of Latin music today: reggaeton (nacla.org/reggaeton-nation). Historically, the genre found itself entangled in a constant battle with Puerto Rican political figures, who perceived reggaeton negatively due to its explicit lyrics and provocative dance (perreo). Beyond these criticisms, reggaeton has been condemned for promoting machismo , claiming it to “promote rape culture, male domination and contribute to dehumanizing women” a (Barberà Romero 41). For years, its biggest stars perpetuated these narratives, offering little space for feminist discourse or diverse representations of gender.

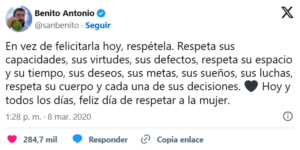

However, Bad Bunny has emerged as a powerful exception to this trend. Initially gaining fame for his trap music embodying reggaeton’s aggressive masculinity, Bad Bunny has undergone a significant transformation as an artist and advocate. Over time, she has become a vocal supporter of gender equality, challenging the genre’s machismo. Through his platform, he has challenged reggaeton’s misogyny, offering an alternative form of masculinity, one in which women are respected.

Bad Bunny’s collaborations with feminist artists, critiques of violence against women, and support for women autonomy demonstrates a new direction for reggaeton, reimagining its potential as a tool for social change. By analyzing his evolving discography, this exploration highlights Bad Bunny’s commitment to fostering empowerment. While feminist critiques demonstrate areas for growth, his transformative progress illustrates the genre’s potential as a platform for cultural dialogue and social change. Ultimately, Bad Bunny’s evolution as an artist reflects a broader shift in reggaeton, redefining its machista roots and navigating the complexities of feminist advocacy with authenticity and ambition .

Context

Reggaeton, a genre deeply rooted in Puerto Rican urban culture, has faced persistent criticism for its hypersexualized portrayal of women and emphasis on traditional machista ideals. Themes of male dominance, female objectification, and perreo has sparked disapproval. Many early reggaeton artists noted the resistance they faced, remembering how “Many people tried to stop us” from making more music (nacla.org/reggaeton-nation). Early reggaeton , including Bad Bunny’s intital work, was often explicit and sexual, demonstrating a noticeable shift with his recent work.

This evolution is particularly significant when contextualized within the broader framework of machismo in Latin America, where domestic violence and gender-based oppression persist. Alarming statistics illustrate how “In 2022…4,050 women were victims of femicide…26 countries and territories of Latin America and the Caribbean” (www.cepal.org). Additionally, “In the Caribbean, 46 women were victims of…gender violence” (www.cepal.org). These numbers demonstrate how cultural norms surrounding masculinity contribute to violence against women, further emphasizing the need for societal change.

By addressing these issues through his music, Bad Bunny is transforming the reggaeton industry into a platform for social advocacy. His work challenges the genre’s historical misrepresentation of women and introduces feminist ideals into a space largely dominated by men.

Recognizing Bad Bunny’s Early Adoption of Machista Tropes

Early in his career, Bad Bunny’s music aligned with traditional reggaeton machismo, reinforcing patriarchal narratives.

Reduction of Identity to Appearance:

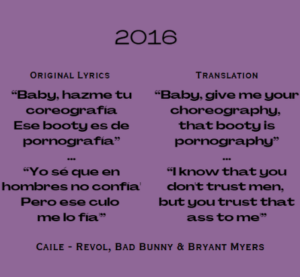

In many reggaeton songs, women are overlooked and reduced to physical features, lacking names or personalities. In “Caile” (2016), Bad Bunny’s lyrics (referenced above), demonstrates this reduction, emphasizing the “assignment of their identity to their asses” (Díez-Gutiérrez 140). The bodies described conform to beauty standards found in sexual fantasies shaped by traditional machismo. This portrayal transmits a problematic message: only women who fit these narrow stereotypes are deemed worthy of male attention. Ultimately, such narratives imply that a woman’s value is tied to her body, reinforcing societal pressures and limiting diverse representations of beauty and identity.

Macho Culture:

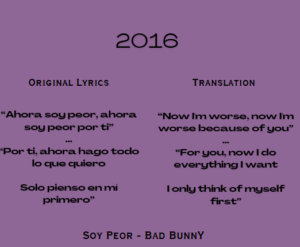

Another recurring theme in reggaeton is the reinforcement of traditional machista ideals, portraying men as the dominant partner that exerts “control and possession”, while expressing “misogyny by portraying women as bad…or liars” (Díez-Gutiérrez 141). In “Soy Peor” (2016), the lyrics (referenced above), portray Bad Bunny as a victim, placing blame onto the woman for his negative transformation. This refusal to take accountability, combined with framing himself as the victim, demonstrates a common machista tactic. Additionally, the emphasis on putting himself above all else in the aftermath of a breakup reinforces a stereotype of men suppressing emotions to maintain dominance. This rejection of emotional vulnerability aligns with the genre’s historic portrayal of traditional masculinity in which strength or superiority is equated with emotional detachment.

Ultimately, Bad Bunny’s reflect the genre’s deep ties to machismo, reinforcing ideas of male dominance and superiority. These tracks provide a baseline for understanding his evolution, marking a starting point in his shift from upholding traditional masculinity to becoming a platform for progressive social change.

Bad Bunny’s Evolving Feminist Advocacy: Imperfect but Pioneering

In his later work, Bad Bunny begins to challenge traditional gender roles. However, his efforts have been critiqued for purple washing–where feminist ideologies are used to cover up the misogynistic elements in reggaeton (Hoban 2). Despite his progressive intentions, his work continues to perpetuate problematic stereotypes, raising questions about the depth and authenticity of his feminist advocacy.

First Example:

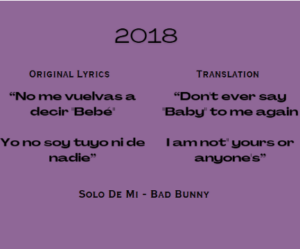

Women have critiqued Bad Bunny’s attempts to position himself as an ally, highlighting moments where his actions has inadvertently perpetuated the silencing and erasure of women in the genre. For instance, in “Solo de Mí” (2018), the lyrics (referenced above) adopt a male perspective, evident in the use of “tuyo” instead of “tuya“. While the song addresses themes of empowerment and autonomy, its impact could’ve been enhanced by featuring a female artist to vocalize the experience from a woman’s perspective. Including a woman’s voice wouldn’t have solely strengthened the song’s message, but also provided a platform for female representations within an industry where their voices are often marginalized.

Addressing the Critics:

The accompanying music video, (released a day after the song) adds a new layer to the narrative and addresses some of the critics’ concerns. At the start, a young woman nervously lip-syncs the song in front of a microphone, and her face gradually becomes battered, visually confronting the issue of gender violence against women. Towards the end of the video, the tempo switches into something more upbeat, symbolizing the woman’s transformation into a survivor who finds strength to leave the broken relationship. This is especially powerful as she lip-syncs, “Y no me vuelvas a decir “Bebé””, showcasing a direct rejection of her abuser. Additionally, the visual lyrics in the video change from “tuyo” to “tuya”, signaling the perspective shift to a woman’s voice.

These visuals portray “women…as assertive subjects”, reclaiming control over their lives (Barberà Romero 43). The protagonist’s ultimate act of dancing and celebrating alongside Bad Bunny reinforces his stance against the mistreatment of women. While featuring an actual female vocalist could have enhanced the song’s authenticity, this video marks a significant departure from reggaetón’s traditional themes.

Second Example:

Bad Bunny then released “Yo Perreo Sola” (2020), a track celebrated for its feminist message but critiqued for its visuals. His exaggerated features in the music video, such as large breasts and a tight, red latex outfit, was criticized for perpetuating stereotypes of the exotic, hypersexualized Latina. Critics argue that his portrayal reflects “social constructs developed within a culture of systemic inequality”, with his moving/dancing reflecting the traditionally sexualized performances of women in reggaeton videos (Álvarez Trigo 5). This undermines his attempt to critique hypersexualization, instead reproducing the fetishization of Latina bodies.

Despite this imperfections, his inclusion of Nesi’s female voice represents progress, as it asserts a woman’s desire to dance independently, without needing a man. However, Nesi’s lack of credit in the song reveals another layer of erasure, highlighting Bad Bunny’s continue struggle to fully represent the female narrative instead of continuing to have them “invisible” in the industry (Álvarez Trigo 4).

Addressing the Critics:

Despite its imperfections, the track deserves recognition as groundbreaking. At the time of its release, few, if any, reggaeton artists had shown the capacity to foster understanding and bring narratives of empowerment within Latinidad. This song reimagines perreo as a symbol of autonomy for women, offering “a new reading of this performative act “, one in which women take “control of these movements for her own pleasure” (Barberà Romero 42). The lyric, “Te llama si te necesita, Pero por ahora está solita”, emphasizes a woman’s independence, reinforcing that women should not be criticized for their self-sufficiency.

The accompanying music video provides significant visual reinforcement of this message. For example, the sign “Ni Una Menos” references the Latin American movement against gender-based violence, showing Bad Bunny’s stance on sexual violence (Álvarez Trigo 6). Additionally, in the same green clip, we see the sign “Las Mujeres Mandan” (Women are in charge), directly challenging reggaeton’s traditional submissive portrayal of women. Lastly, the video concludes with a black screen displaying the words “Si no quiere bailar contigo, respeta. Ella perrea sola” (If she doesn’t want to dance with you, respect her. She twerks alone), explicitly advocating for respect and autonomy.

By opposing machismo and promoting empowerment, Bad Bunny challenges traditional norms within Latinidad. This shift highlights how perreo can be reclaimed as “a way of liberating the body” for women who want to solely dance for their own enjoyment (Barberà Romero 42).

While not perfect, Bad Bunny’s work represents a pivotal shift within reggaeton, highlighting how “hegemonic roles traditional conceptions of gender have imposed are changing” (Álvarez Trigo 6). Aside from empowering women to be strong and independent whether it’s in regards to a relationship or perreo, Bad Bunny has also paved the way for reimagining reggaeton as a genre capable of confronting social and political issues.

Recent Advocacy: Stronger Stance on Gender Issues

In his most recent work, Bad Bunny takes an even stronger stance on gender equality, giving women more agency in his music. These improvements suggest he has listened to critiques and evolved as an artist.

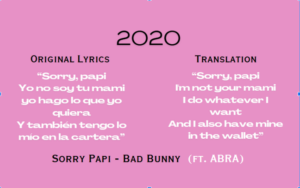

In his song, “Sorry Papi” (2020), released exactly 8 months after “Yo Perreo Sola”, Bad Bunny expands on similar themes of empowerment and autonomy, this time incorporating a female voice to emphasize the message. Featuring ABRA, the song takes the form of a “conversation” between male and female protagonists, she asserts her independence and sexual agency. ABRA’s lyrics reject societal expectations that women must accept men’s advances, explicitly stating her financial independence and lack of reliance on him.

Furthermore, ABRA challenges traditional gender roles, presenting a narrative where women openly express their freedom and refuse to conform to submissive stereotypes. By pairing ABRA’s confident voice with a reggaeton beat, and giving her proper credit as a featured artist, Bad Bunny, provides a platform for female empowerment. This collaboration marks a significant shift in the genre, emphasizing women’s agency in romantic and sexual dynamics.

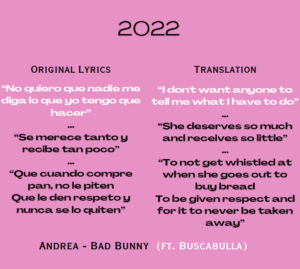

Bad Bunny once again addresses the enduring issue of domestic violence against women in his song “Andrea” (2022). This track highlights a female perspective through the voice of Buscabulla’s female singer, giving her proper credit and a platform to enhance the message. In the context of rising femicide rates, “Andrea” becomes a powerful call for cultural change, advocating for respect for women’s bodily autonomy and agency.

The character of Andrea, portrayed by the female voice, represents women everywhere “with the desire to grow, be free, dream, be respected and understood”, according to Bad Bunny himself (peopleenespanol.com). The lyrics sung by Buscabulla emphasize a woman’s desire for independence and rejection of control, while Bad Bunny’s verses criticize societal norms that perpetuate disrespect towards women. His lines highlight daily struggles like catcalling and the lack of appreciation women endure. Overall, he “continues to be a champion for female empowerment and…to advocate against gender-based violence” by advocating for women and their rights (peopleenespanol.com).

Music like this serves as a powerful tool for advocacy, showcasing how a “reggaeton song can help denounce sexist behaviors that occur within this same genre” effectively (Barberà Romero 44). Ultimately, it illustrates the potential for reggaeton to evolve as a space for progressive change.

The Future of Reggaeton: Can Bad Bunny’s Feminist Vision Transform the Genre?

These positive social media reactions from women further emphasizes Bad Bunny’s significance and impact in the music industry. Women worldwide are expressing their appreciations confirming the empowerment and sense of recognition they feel from his music. Such reactions don’t solely validate Bad Bunny’s message but also demonstrates the broader cultural and emotional connection his advocacy has within the community.

Bad Bunny’s cultural and political impact extends beyond the traditionality of reggaeton, positioning him as a transformative figure in the music industry. By challenging machismo, deconstructing gender norms, and addressing social issues such as domestic violence and femicides, his work serves not solely as artistic expression but also as a form of activism. While his earlier works may have contributed to the misogyny present in the genre, his evolution demonstrates a shift towards creating a more inclusive and socially conscious space. This analysis highlights how Bad Bunny’s music encourages critical conversations regarding gender, power, and representation, blending artistic identity with advocacy.

This progression showcases reggaeton’s potential to evolve into a platform for meaningful activism. Through his efforts, Bad Bunny invites listeners to question how deeply ingrained social norms are reflected in the media and encourages artists to continue challenging these principles. His efforts remind us that change often begins with bold actions in unexpected spaces, attracting attention and inspiring others to follow in their own creative manners. Bad Bunny’s commitment to making reggaeton more inclusive and socially aware motivates ongoing dialogue–whether it’s in support or critique–to collectively dismantle systems of inequality.

Works Cited

Álvarez Trigo, L. (2020). Bad Bunny Perrea Sola: The Gender Issue in Reggaeton. PopMeC

Research Blog, https://drive.google.com

Anonymous. (2023). In 2022, At Least 4,050 Women Were Victims of Femicide in Latin

America and the Caribbean: ECLAC. United Nations. https://www.cepal.org

Bad Bunny. (2016). Caile [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2qTgFv6XlM

Bad Bunny. (2016). Soy Peor [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ws00k_lIQ9U

Bad Bunny. (2018). SOLO DE MÍ [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rbprAR_Reg

Bad Bunny (2020). SORRY PAPI [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyAl7Oo9zVs

Bad Bunny (2020). YO PERREO SOLA [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtSRKwDCaZM

Bad Bunny (2022). Andrea [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjvTQTGogUM

Barberà Romero, S. (2023). Feminist Takes on Reggaeton. Cromohs, 5(1), 40–49.

Díez-Gutiérrez, E. J., Palomo-Cermeño, E., & Mallo-Rodríguez, B. (2023). Education and the

reggaetón genre: does reggaetón socialize in traditional masculine stereotypes? Music

Education Research, 25(2), 136–146. https://www.tandfonline.com

Hoban, D. (2021). Bad Bunny’s Purplewashing as Gender Violence in Reggaeton: A Feminist

Analysis of SOLO DE MI and YO PERREO SOLA. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

https://login.ezproxy.prhttps://www.proquest.com

Montalván, K. (2022). Bad Bunny Spills the Deets on the True Meaning Behind His Song

“Andrea”. People, https://peopleenespanol.com

Negrón-Muntaner F., & Rivera, R. (2007). Reggaeton Nation. NACLA Report on the Americas,

40(6), 35-39. https://nacla.org/news