Where two memorials for the civilian victims of the Second World War begin and end.

By Vivien Wong

In the late 1960s, when sculptor Stelios Triantis was commissioned by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture to design a memorial for the Distomo Mausoleum, he found inspiration in the metopes—rectangular slabs between triglyphs on a Doric frieze—of ancient Greek temples. The most famous incorporation of this architectural element appears at the Parthenon: almost a hundred metopes adorn the four sides of the temple, each sculpted with a scene from a mythical Greek battle.

Triantis crafted a total of seven metopes for the Distomo Mausoleum. Together, they narrate the German occupation troops’ massacre of over 200 inhabitants of the village of Distomo on June 10, 1944. In these panels, violence conveys tragedy rather than triumph: the forced march of six faceless figures, three men slumped on the ground, three women weeping. A stiff German soldier aims his machine gun at a family huddled around a square table; the father, weaponless, stands and leans over the table toward the soldier.

Normally, metopes sit atop the vertical columns of a temple. Triantis’s panels, however, span a horizontal column—marble—a few feet off the ground. Perpendicular to this lies another column, engraved with the names and ages of the massacre victims. The two axes converge at the mausoleum’s cubic ossuary. Each year, on the anniversary of the massacre, relatives may enter and light candles inside. Otherwise, the room is closed to the public.

A slatted window allows visitors like myself a partial, obstructed glimpse of the victims’ remains inside, displayed in a wall of shelves to the right. The skulls are of varying condition: some cracked, others missing a mandible. Counted together, they still number fewer than the names engraved outside.

*

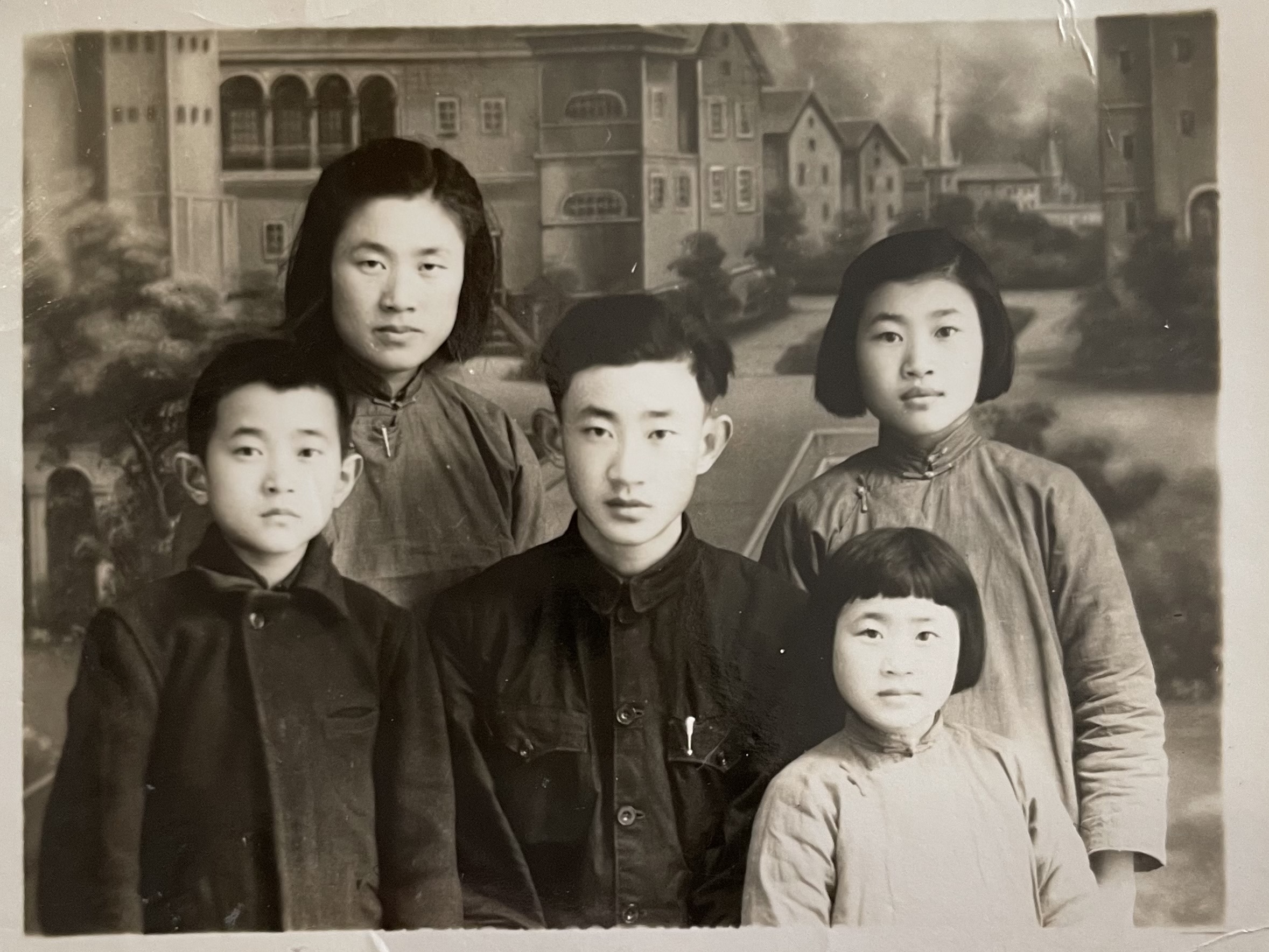

When my grandfather, whom I call Ankong, was seven, the Japanese invaded his hometown of Linyi, in China’s eastern province of Shandong. By the time he’d turned twelve, his father had been tortured, executed, and beheaded. He had been a high school principal, and as the rumor goes, one of his students had accused him of being part of the Japanese opposition movement.

The Japanese occupied Linyi for seven years, until the end of the Second World War. After his father’s death, Ankong’s mother disappeared with his baby brother. His younger siblings sent off to an orphanage, Ankong fled south—the first leg of an exodus that eventually took him to the Philippines. There, in a village on Negros, he met my grandmother, my Amma, whose father, brothers, and uncles had once lined up before the Japanese machine guns and lived.

There’s a picture of Ankong, then sixty-eight, during his final trip to Linyi. He’s kneeling in the dirt of the Cemetery of the Revolutionary Martyrs of East China, which honors those who were killed for resisting the Japanese. Behind him crouch my mother and my aunt. Both are smiling; he is not. A bouquet of flowers sits in the center.

My mother used to tell me Ankong’s father was buried in that cemetery. Recently, she returned with a correction from Ankong’s sister, who said their father was buried in a different cemetery in Linyi. Only Ankong knows—or once knew—the location. Years ago, he had tried to visit his father’s grave there and found the area razed for construction. “All the tombs and tombstones were gone,” my great-aunt told me, “and turned into flat land.”

My mother once said that she’d seen my great-grandfather’s name on a plaque when she visited the Cemetery of the Revolutionary Martyrs of East China. Now she’s not certain. “I might’ve made that detail up,” she said when I called her in July. “I don’t know his father’s name was even there.” When they were in the cemetery, my mother remembers hearing Ankong say he was happy that his father was finally being commemorated. “But I think he just wanted to have a place to go to remember,” my mother later told me.

*

Proposals to build a memorial for the victims of the Distomo massacre began in 1944, though the mausoleum was not completed until 1976. According to Amalia Papaioannou, the historian who curates Distomo’s Museum of the Victims of Nazism, one survivor’s son had “never experienced a caress or a sign of tenderness from his own father,” whose brothers and fathers were killed in the Distomo massacre, until the day the bones of his father’s family were transferred to the mausoleum. “That was the first day that he showed affection to his son,” she said.

Papaioannou is herself a third-generation descendant of Distomo massacre survivors. Growing up, she told me, “we didn’t hear any other story, any other fairy tale from our grandmothers and grandfathers, except the story of the victims of the massacre. Again and again and again.”

“The memory is a debt,” Papaioannou explained. “The debt has become a way of life.” The biggest concern in Distomo, she added, “is that this memory will die together with the last survivors.”

*

Since leaving China, Ankong has stopped talking about his father. He prefers to think of his mother and youngest brother as long buried. But some inexplicable force compels his daughters and grandchildren, I among them, to continue exhuming their bodies, as if knowing exactly how they were killed or what they were wearing when it happened can make murder less bloody.

Each Christmas, we gather—in Ankong’s living room, or else over Zoom—to hear about the day the Japanese invaded. The debt is paid: again and again and again. ♦