Each Friday by noon, two members of the class will send 300-500 word responses to the most recent seminar to CNW and KN, who will post these here. As our final project develops, specific assignments toward that work will appear below as well.

September 2:

Response #1 (CW)

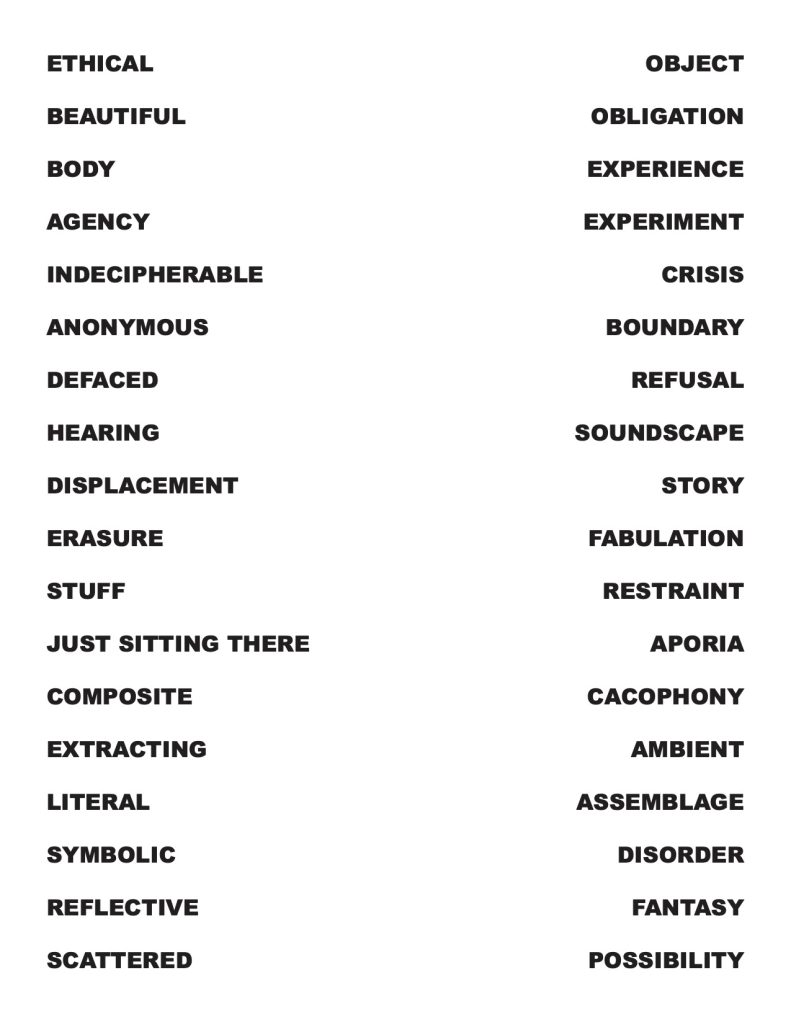

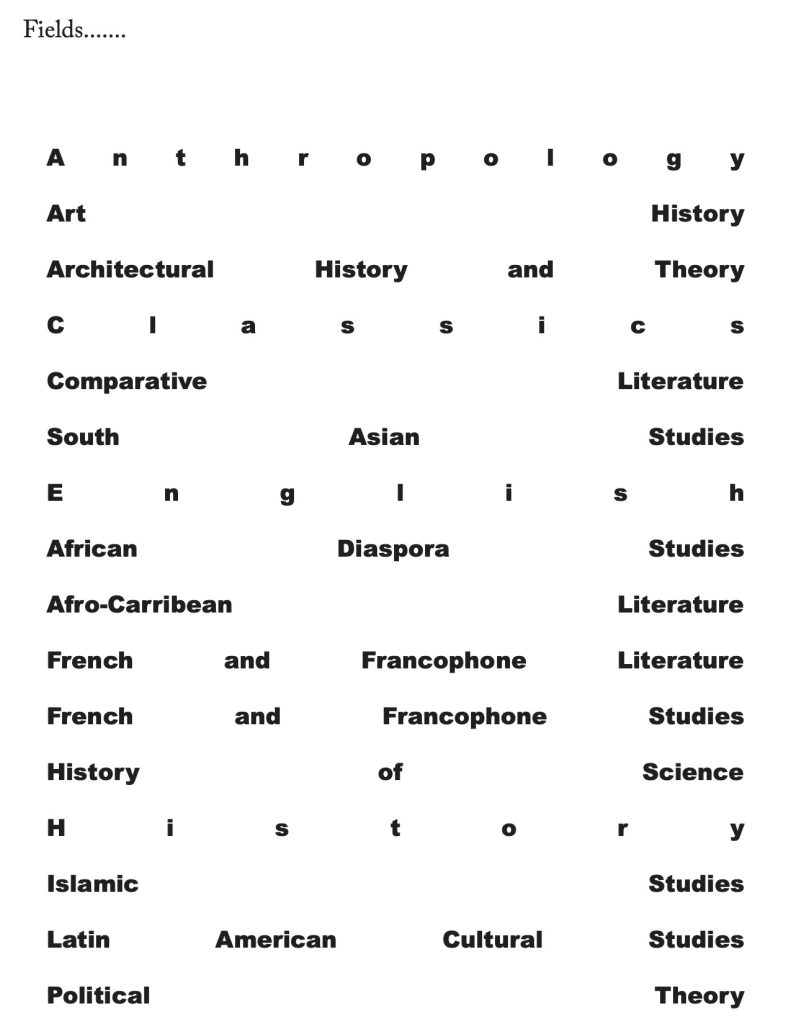

What an exciting start to the seminar. The room was full, the oxygen in somewhat short supply. We began with introductions. Departments of great variety are represented in this year’s group: English, French, Classics, Music, Art and Archaeology, Comparative Literature, Anthropology, Spanish and Portuguese, Architecture, History, East Asian Studies, Politics, Religion. The group is a particularly creative one, with talents in bookmaking, dance, theater, gardening, DJing, vinyl pressing, poetry, fiction, speculative writing, creative nonfiction, social media, design, photography, fiber arts, painting, and probably a few that I’m forgetting.

We went through some of the course logistics and spent a good amount of time talking about potential directions for the final collaborative project. The self-coalescing syllabus, the general structure of each session, and the exciting lineup of guests were presented. KN and CNW tried to convey a general sense of the mission of HUM 583 and outline possible topics of discussion for the course: How do universities work? What are their visible and hidden mechanisms? Who powers the university (financially, administratively, pedagogically)? Why do disciplines exist as they do? Why are they called what they’re called? What are their histories and potential futures? What is the relationship between a department and a discipline? How can one’s research materials be repurposed creatively? What is public humanities? What is interdisciplinarity? A particularly thorny question: What in the world is anti-disciplinarity, a key word in the seminar’s title? How should we think about our roles as teachers, researchers, advisers, mentors, administrators, and community members? These are just a few of the topics we’ll tackle throughout the semester.

CNW showed examples from last year’s iteration of HUM 583, when we converted our classroom into a kind of walk-in camera. The table was covered with a cloth that had been treated with light-sensitive chemicals. We suspended UV lights above the table and set up an old-fashioned transparency projector. Then, we followed this protocol:

ON THE TABLE

On December 4, willing participants in HUM 583 will gather for a seminar session aimed at the collaborative activation of a final project for “Interdisciplinarity and Antidisciplinarity” in 2024. What follows is the “Protocol” for the 60-minute session that will center that last meeting of the course. This session will focus on the table itself as a locus of exchange and encounter (with particular focus on humanistic/disciplinary/university life), and on “tabling” as a charged/ambiguous/ambivalent activity.

IN ADVANCE:

- The seminar table will be prepared with a photosensitive layer, and the room lit in such a way as that the table surface will, to some extent, “document” tabletop activities in a photogram form.

- A transparent receptacle will be placed at the center of this table (and some other materials will also be made available, as below).

- Arrangements will be made for:

- Each participant to SCREENSHOT three excerpts from the reading for this class (including, as relevant, any marginal annotations, etc.); AND two images of tables (such as feel interesting/expressive – one of which needs to have some relationship to the DISCIPLINE from which each participant comes.)

- All of these materials will be transferred to TRANSPARENCIES, in advance of the final session, cut to size (ideally, each image and text excerpt not to exceed 8.5 x 5.5).

- Everyone is also invited to bring to the final seminar any additional paper/notes they wish — particularly materials they might consider folding or cutting. (Various textual interventions/operations to be discussed in advance.)

IN THE FIRST HOUR OF THE SEMINAR:

- Each participant will have 2.5 minutes to PROJECT (on an overhead projector) the transparencies of their screenshots of texts/images — reading and/or showing as they wish.

- After that “share,” all of the images and texts will be laid out on the table — “tiled,” as it were, and fixed there with tape or pins. This is the “Starting Position” for the PROTOCOL (below).

PROTOCOL FOR THE HOUR OF ACTIVATION/DOCUMENTATION:

- Photogram-registering light is illuminated, to begin exposure of the table and its assembled texts.

- 20 minutes: ANNOTATION PHASE – in silence, and without disturbing the location of the texts and images on the table, participants are invited to make a series of annotations (in sharpie, on clear transparency cards); these are laid on or near what they address. These may be questions, comments, replies to questions, etc.

- 20 minutes: “TABLEWORK” PHASE – in silence, and going around the table by turn (one may always “pass”), each participant makes an intervention on the table. This might be a “move” (stacking two texts, rearranging a text or annotation), or an “operation” (folding or covering a text, etc.). Everything is to be left “on the table.”

- 20 minutes (or until no further move is possible): “TABLING” PHASE – in silence, and going around the table by turn (one may always “pass”), each participant removes something from the table, and may keep it, or place it in the clear box at the center.

FIN

Response #2 (KN)

I.

Curtains raised on the new school year.

Twenty-four players around the table, with some needing to sit behind others to fit everyone in the space.

Between preliminaries and introductions, this felt like a rehearsal—in particular, that moment when the cast first assembles in a space to begin the process of collaboration. Having sat through such rehearsals at another point in my life, I remember how the room hums with a certain of kind of energy. It might be anticipation, or excitement, but it could just as well be anxiety or stage fright (when it comes time for you to speak up). The hum has different frequencies, but it’s there. It registers a collective feeling out—again, a rehearsal (which has its own protocols of stagey-ness) of the work we’ve committed to do together.

Twenty-four introductions around the table: a familiar ritual, though naming it explicitly helps me appreciate its periperformative (Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick) qualities.

II.

Something about CNW’s sharing of her object—her demonstration of what we expect from this exercise—must have made me think of curtains. I did not have curtains on my mind when I walked into class. And it did not come immediately to me when CNW shared her object: a pattern from a sewing kit, produced with instructions in French and English, dated the 1990s. The pattern was not for curtains, though I suppose the way CNW unfurled the thin paper from the packet and set it on the table reminded me of a wispy curtain pushed by a gentle summer breeze.

Several students had mentioned interests in theater, music, song, sound: performance in the broad sense of the word. In retrospect, this thread may have interlaced with CNW’s mention of textiles and texts. I could see—or, better, sense—a pattern that disclosed the connections between the material and the figurative, practice and thought.

III.

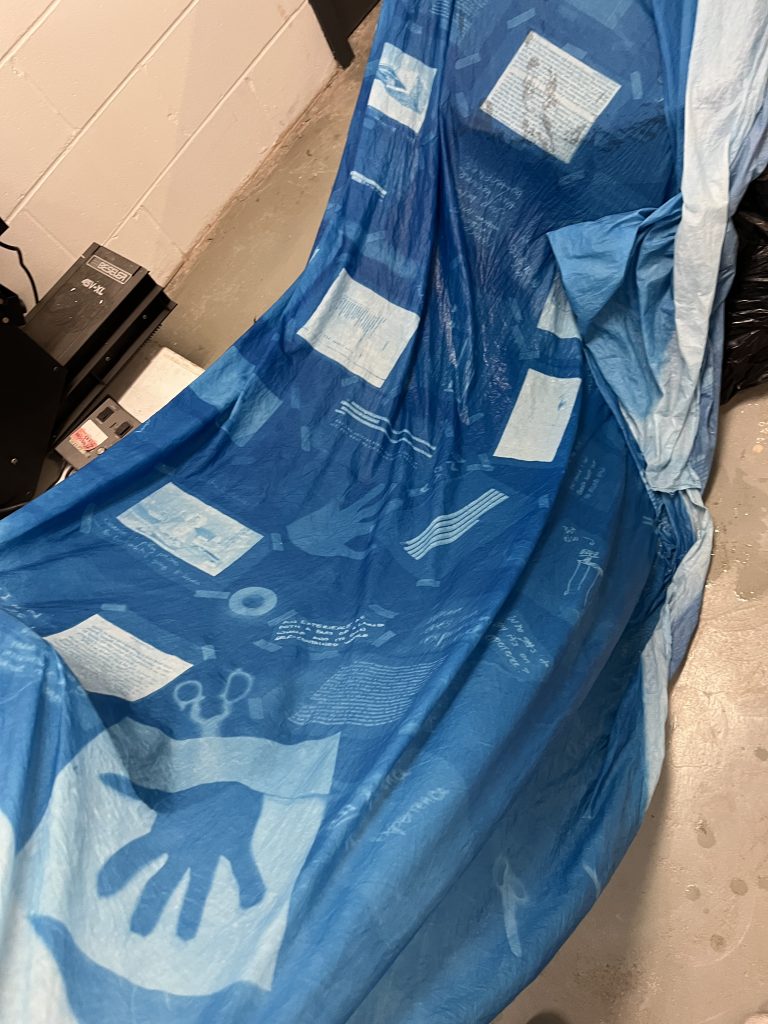

CNW had shared with me last year’s seminar’s final project prior to class. I had seen her unbox the large cyanotype sheets and wrangle with their unwieldy dimensions. (You know what it’s like to manipulate a sheet by yourself: splayed arms, tucked chin, etc.) I admit I could not appreciate the project in the (relatively) cramped space of a professor’s office. But I also wondered exactly what the group might have been going for in this experiment. (Intent, such as it is, was clearer with previous seminars’ publications, including the card game.) The cyanotype series did not seem to carry the same weight as the other projects.

My skepticism was amplified when the two of us—CNW and me—spread the sheets on the table during our class break and put the transparent box of ephemera? supplies? on its proper place on the tableau. I tried to move the box to the side of the design, not knowing that it had to go above its shadow, as CNW explained it to me. I saw it for the first time in its full display along with you in the meeting.

My thoughts on the project changed completely when CNW presented the process of creating the work. Beginning with a summary of the seminar’s playing on the material-metaphorical implications of tables and tabling, she walked us through the project’s planning and production stages, with an emphasis on their day of executing the project. CNW’s presentation revealed how that execution involved creating a performance space out of the very room we were sitting in. The table, I realized, was an essential part of the performance, with students moving around each other as they shared their objects and media and placed them on the sheets. (This data was captured by CNW’s camera, which she had set up in the far corner of the room.) By reconstructing their process, CNW gave me, and us, a way of appreciating the cyanotype series as a happening, a series of moves or gestures—acts of sharing—whose evidence of enactment could only be captured in shadow. The seminar’s project, then, was a performance piece, not necessarily the cyanotypes themselves. That was my takeaway.

And what more appropriate way to end a (theatrical) performance than with the curtains coming down? The seminar’s dash to develop the sheets so that they could share their work at the IHUM Open House was the perfect way to end the show. A debut, curtains raised: sopping and dripping, the sheets could be seen in their heraldic glory (an effect sealed by the Oxfordian milieu of the Chancellor Green Rotunda). But what I saw, through a retrospective account of the full performance, was a grand finale: a theatrical conclusion to the seminar’s collaborative process.

Curtains, of course, can symbolize both: an opening and a closing. And, like tables, they signify in registers that lie well beyond the theater. (“It’s curtains for you,” one can imagine a villain from Dick Tracy saying.) So, as CNW’s presentation came to an end, we were left with an indelible image of last year’s seminar’s work: one that announced itself to the world and folded itself up in the same gesture.

September 9:

Response #1

- Beginning at the end of our discussion,

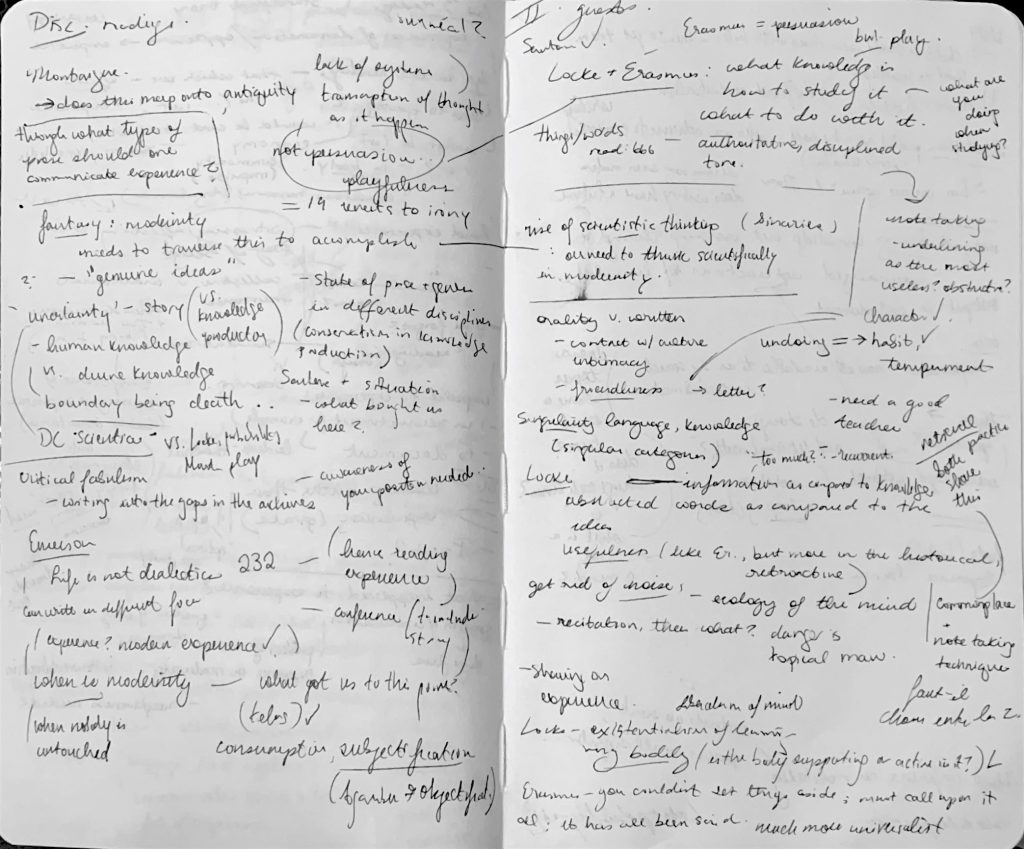

I will reveal a bit of my process in writing this discussion post. I’ve brought myself to write with my notebook from Tuesday’s seminar placed beside me, an artifact of that conversation which I put together with an increasing degree of self-awareness. Our seminar started off as a conversation about the etymology of the word “Experience”.

ex (“out”) + peritus (“expert”), peritus being the present past participle of periri (“to go through”), which borrows from the Proto-Indo-European root –per: to go through, to carry forth, to try or risk.

We ended with a similar gesture to that of reaching back to linguistic origins when our guests JD and FF led us to Locke and Erasmus as potential ‘roots’ for our understanding of study and notetaking methodology. Like in the ways our use of the word “experience” today does not reflect a progression of the word’s meaning from one definition to a more modern one – being instead a constellation of meanings and derivatives that have compiled over time – so too did we come to articulate as a group how our methods of collecting, engaging with, and demonstrating our knowledge of study has not been a linear progression ‘from Quintilian to Erasmus to Locke.’ JD’s comment “Here we are again!” became a refrain of the discussion – or, at least, it appears as one in the notes I recorded throughout.

Why self-awareness? What I sit with now, in the moment of writing, is a series of pages in a style of notetaking that features circled terms and lines drawn across the page, arrows indicating the progression of ideas as they were raised in discussion, questions I ask in the margins between copied quotes pulled from conversation, and a designated place in the top right corner for connections to my own research, a place where I collect the questions that I will pursue when I am alone with my notebook again. It is a record of what FF referred to as the “internalized interaction of knowledge,” which we came to characterize more as a “loop” of internalizing and externalizing our engagement with an object of study. Evidence of this loop is clear on the pages I consult now. Any sense of linear temporality maybe implied by my practice of drawing arrows between ideas is undone by new connections layered on top in the space of our three hours together, new questions woven into earlier ones (or, which is always exciting, answers are added into the space I left for them, just in case).

I feel okay to elaborate on this here because this is where our conversation ended. I knew I would need to refer to these notes when I volunteered to write this week, and so became increasingly aware of my practice as I was careful to represent the full range of the conversation and prepared to translate them into prose. This movement from note to prose is not an unfamiliar experience to me, although the output is always a bit of a risk – particularly a risk of taking up too much space, I tend to go on… So, to carry forth:

- Going back, before break: brainstorming and indexing

I noted above a brief record of the etymology of “experience” as we use it in English. We also discussed other languages that are represented in our readings and our class:

-French expérience (noun) / expérimenter (verb)

-German erfahrung / erlebnis (this is commented on in the footnotes of our translation of Benjamin). Erfahrung from fahren, to travel or drive, and erlebnis from leben, to live.

-Dravidian languages feature a reduplication that indicates grammatical perfection (an action having been completed), and this syllable is called the same thing as the word for experience, a term which means something closer to ‘to be habituated’.

-The two Korean words for ‘experience’ have distinct uses: one to refer to passing through time, the other described as a more bodily experience, maybe understood as more intense or direct.

-Spanish and Portuguese use the term ‘baggage’ without the negative connotation of this in English. A respected professor bringing a lot of knowledge to a conversation could have a lot of “baggage”.

-Japanese term includes a sense of ‘verticality’ along with experience (progression?).

One also uses possession to describe an experience one has had.

We also elaborated on uses of experience in English:

-Experience economy

-The impulse to experience things: Renaissance fairs, reenactments

-The impulse to document (often as taking a photo) – moment becomes theatrical for the camera

-Gaining ‘XP’

-How do we quantify experience (what if we forget?) – Comment parler des livres que l’on n’a pas lus?

-In what ways is witnessing different from directly experiencing? Observing?

-Collective v. individual memories – Lieu de mémoire

Turning more directly to our reading packet, we began to question ‘what happened to experience,’ particularly the “problem of experience in modernity.” ME raised the question of why Montaigne wasn’t included in the experience packet we were assigned, despite being referenced (at least by Agamben) as the epitome of being fully invested in experience in his approach to the essai (‘attempt’). We spoke of the playfulness in Montagine’s approach, pursuing something closer to the transcription of a course of thought rather than persuasion. The theme of persuasion came up again in the second half of class when we discussed the method of study endorsed by Erasmus.

Some final notes from this first half of class, which I hope to return to next week:

-Our ‘modern’ experience – reflecting on Emerson’s “life is not dialectics” (232) and the reading experience of this text. I think we can continue to question this in terms of Anzaldúa’s work.

-The relationship between ‘uncertainty’ and story/storytelling/narrative. Agamben on Montaigne notes that the only certainty is in death, a boundary that isn’t crossed (or experienced). In what ways do our attachments to certain genres in our various disciplines lend themselves more or less to communicating knowledge? In what ways may they perform certainty?

Response #2

“Experience” is a curated reading collection that seeks to tease readers with a question: What happened to experience? I admit the question baffled me. I found “experience” to be slippery and I prefer solid ground. What kind of experience (as in the ability to recount x after living or having been an oral recipient of y; knowledge or familiarity with a topic, procedure, feeling; individual subjectivity produced by social, cultural, and economic realities)? What language could be used to communicate across our own experiences (disciplinary and personal) to arrive at a discussion of experience that was more than a freeform, vague abstraction?

Then, KN posed the packet’s framing question again: What happened to experience after modernity? How do these writers theorize and respond to changes in individual and collective experience after “modernity” at the level of style/form? Despite inhabiting a room with individuals across disciplines and the difficulty in agreeing modernity’s “time” (from French Revolution versus the Age of Revolutions to the age of exploration or 1492), I was surprised by how the term “modernity” provided a common script to approach the texts. We readily set up the temporal teleology (pre-modern/modern), parsed the false binary opposition we’ve all encountered (traditional/modern), catalogued historical violence (ex: colonial land dispossession), disciplinary formations (separation of sciences), and technology (writing to AI) that have shaped the so-called modern world we recognize today. I can’t decide if the ability for the term to recall a familiar script suggests our education’s failings or successes. Probably both.

The approach to the packet’s question raised in class discussion that I wanted foreground for next week was memory. As discussed, memory probes the limits of conceiving experience as solely individual and raises questions about inheritance, transmission, age (from generational to milieus), forms of remembering (rememory), and the spaces or sites of memory (be it institutional spaces like archives or museums, the natural world [Toni Morrison Beloved’s Jamaica Kincaid’s Mr. Potter both offer poignant reflections on the ocean], or formal/informal memorials). To conclude, here is a link to a project: https://ktown92.com/. Lately, I have been thinking about the ’92 LA rebellion (has nothing to do with my research, simply thinking about my home as I watch my city under attack from a distance). I think of the project as a (digital) memorial and (digital) archive of an event that shaped my experience/my family’s experience. Hope you all get a chance to see.

September 16:

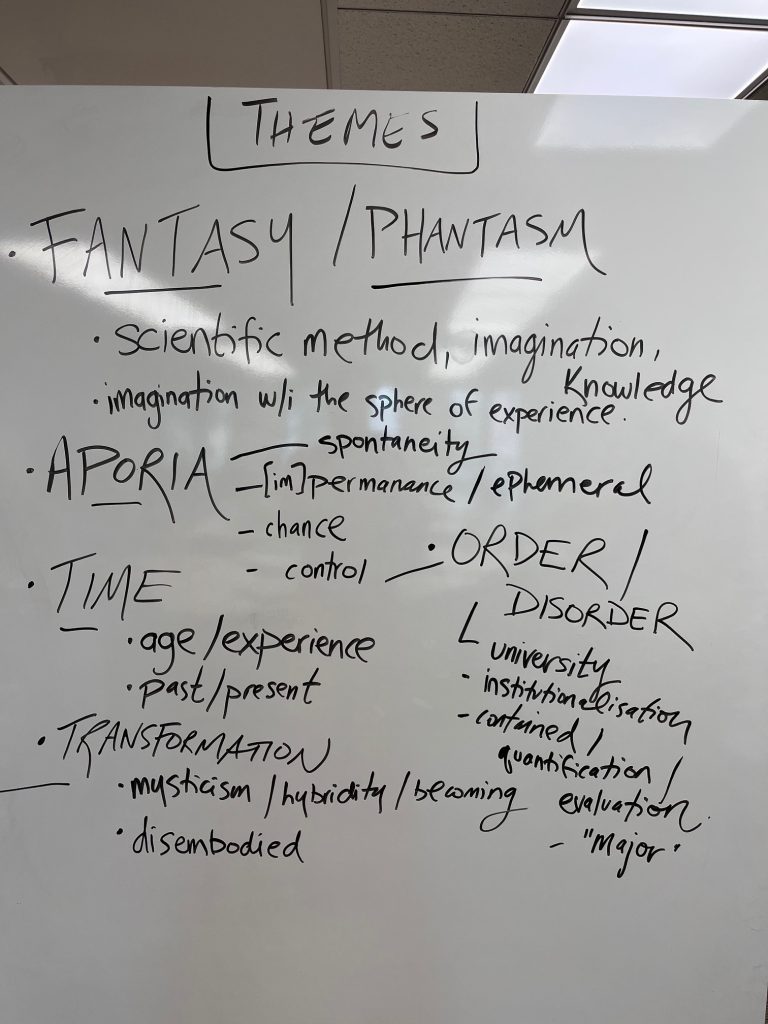

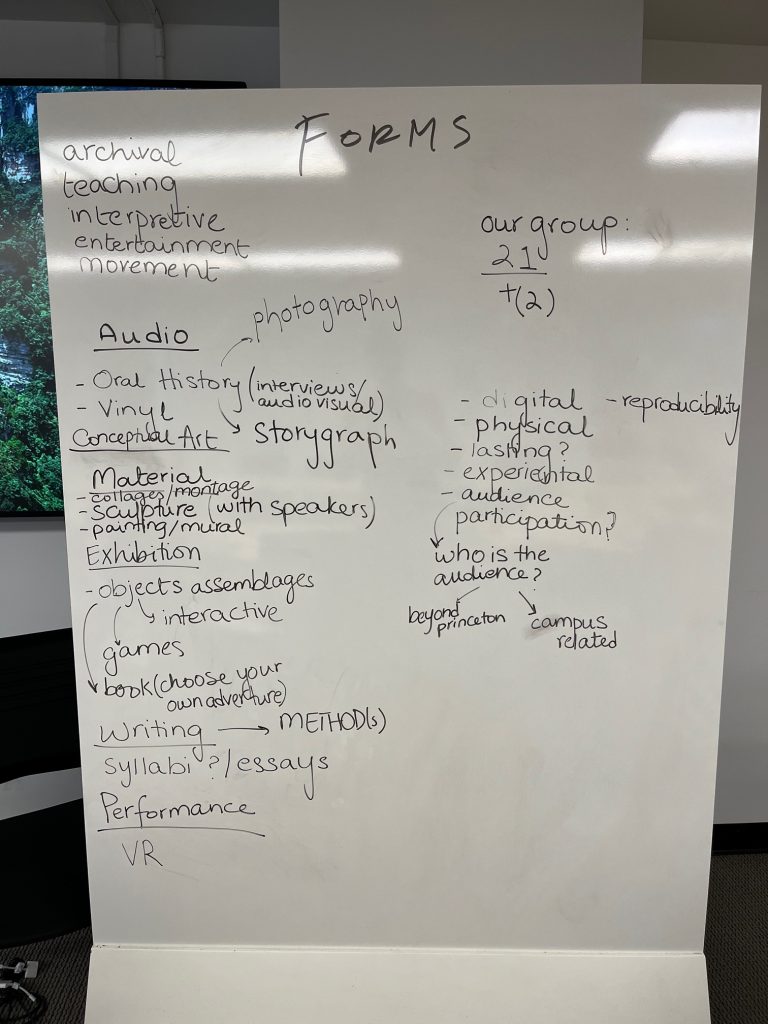

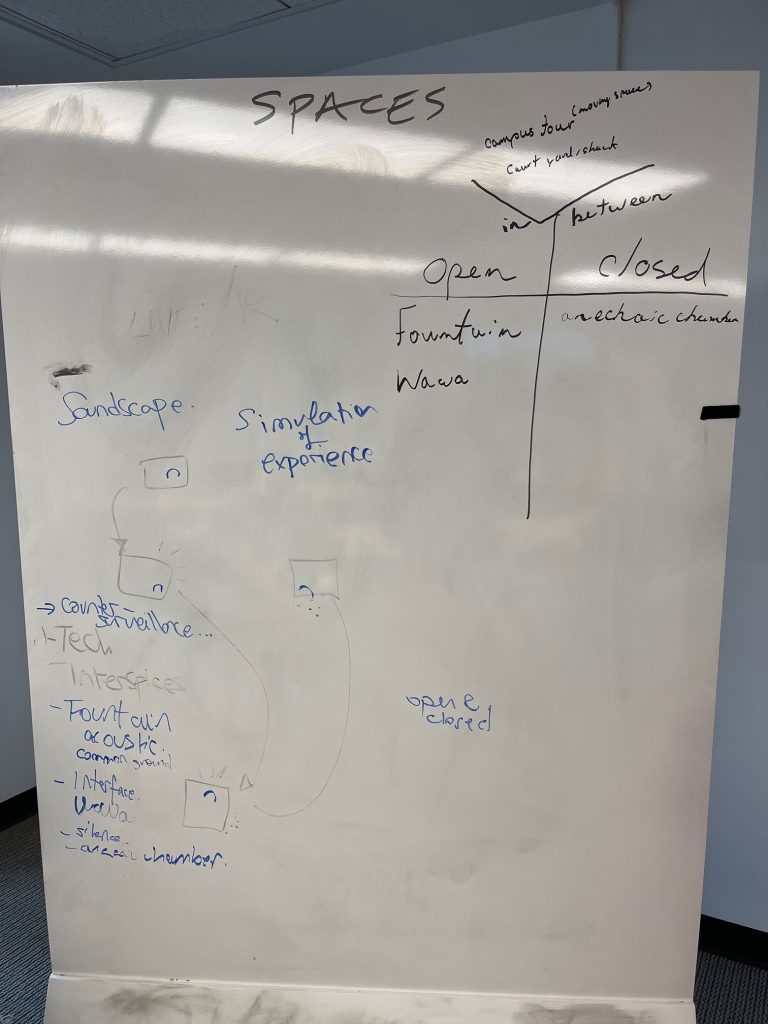

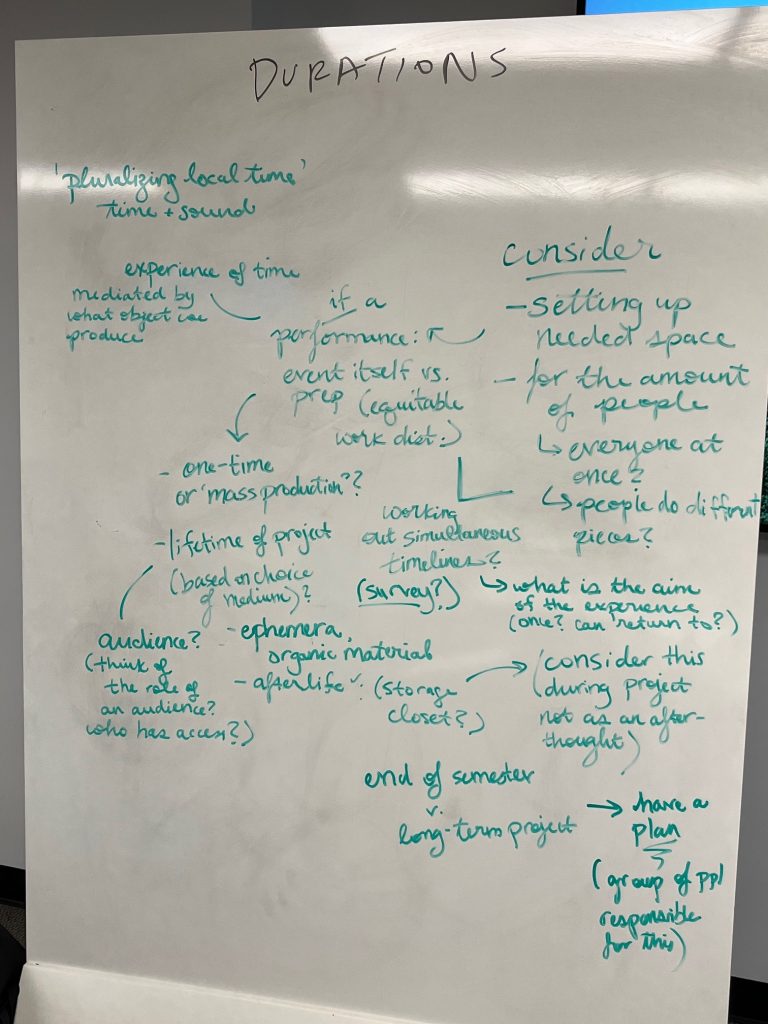

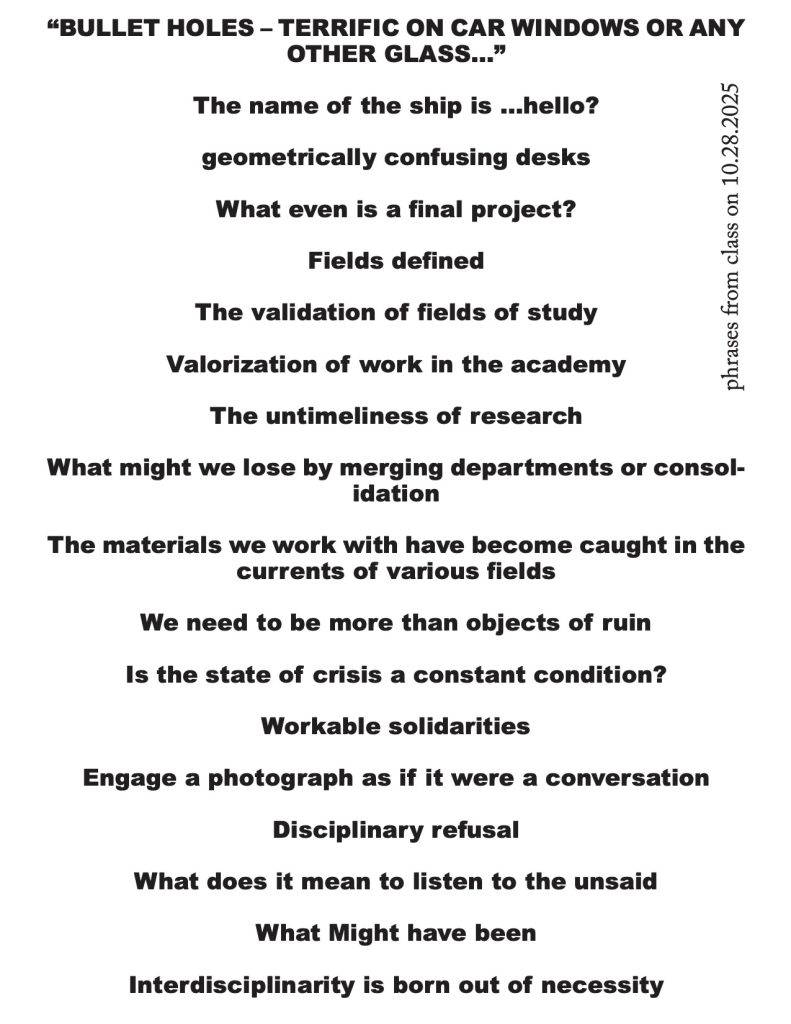

The white boards! The planning for the final collaborative project has begun. Many ideas swirled in our new, strange, netherspace classroom with its modular tables, just behind the ghost library:

Response #1

Though “aporia” factored into only a relatively small portion of this week’s discourse, I find it appropriate to begin with this term and its relationship to our wider themes of discussion. “Aporia” comes from the roots “a- ” meaning “not, without” and from “poros” or “passage” (Etymonline). The term “passage” generally indicates a straightforward movement from point A to point B, but, as we discovered in class, topics such as “knowledge” or “experience” often find us face-to-face with a closed door, or else turning in circles.

The main themes of our discussion this week were the nature of “experience” (a theme carried over from last week), and the question of what constitutes “knowledge,” both topics which brought us to aporia. We discussed the varying interpretations of “experience,” often delving into the mystical or astrological as we sought to make sense of what this word truly meant. We discussed the more concrete forms of experience, that is, the tangible, “real” variety (ex. living through a historical event, attending a talk/play/etc.) , and the type of experience that can be created in one’s own mind, as in the text by Gloria Anzaldúa, in which she creates a sensorial experience of her own through entering a trance-like state. How much credence we lend to each type of experience depends on our culture and also on our personal background, we found.

We discussed knowledge in this context as well, posing the question, “What constitutes knowledge?” and wondering if knowledge must come from experience. CNW drew the conclusion that knowledge + experience = wisdom, showing the link between these related themes. We also discussed how knowledge was once linked to astrology, with LS informing us about the fascinating history of the “knowledge” (the quotes feel odd, admittedly, but I can’t help it) of where venereal diseases came from. She mentioned that they were originally thought to be astrological in nature, having to do with the planets’ alignment. The fact that knowledge can change, and often based on experience, was an interesting edge to this discussion.

Finally, we discussed the transmission of both knowledge and experience, seeking to find an answer to questions like, “Can experience be transmitted to another person?” and “What is the best way to transmit knowledge to an audience?” The first question, we found, is the most relevant when we discuss topics like racism, sexism, and other painful lived experiences. Can a person who has never experienced something like racism or war or poverty truly be made to understand it, or is experience the only way to come by the intimate knowledge of these realities? If so, how can one best transmit the knowledge of these experiences to the audience so that the message is received to its fullest capacity? This is a theme I’m excited to discuss in more depth in our next class!

Response #2

It is the end of week 3 and it already feels our time together is too short. Each reading on experience begets a branching Linnaean tree of etymologies and connections; each idea fractally unfurling, each successive theme revealing new corners to explore.

Nowhere is this more clear than in our final project brainstorm, the focus of the second half of class. We split into four groups, each responsible for a different aspect of our class’ final collaborative project: Themes, Forms, Spaces, Durations. In self-assigned groups, we spent 25 minutes putting ideas on the table (it quickly becoming clear which discursive impulses inspired last year’s project), all the while getting used to our new classroom, with its rhomboid desks and ghost library entryway.

Projects are surprisingly modular. We learned that it’s possible to brainstorm the length and structure of a project without knowing anything about its actual form or subject matter. After the brainstorm was through, we shared our ideas, building a shared tapestry that slowly yielded an emerging consensus, the shape of a viable project.

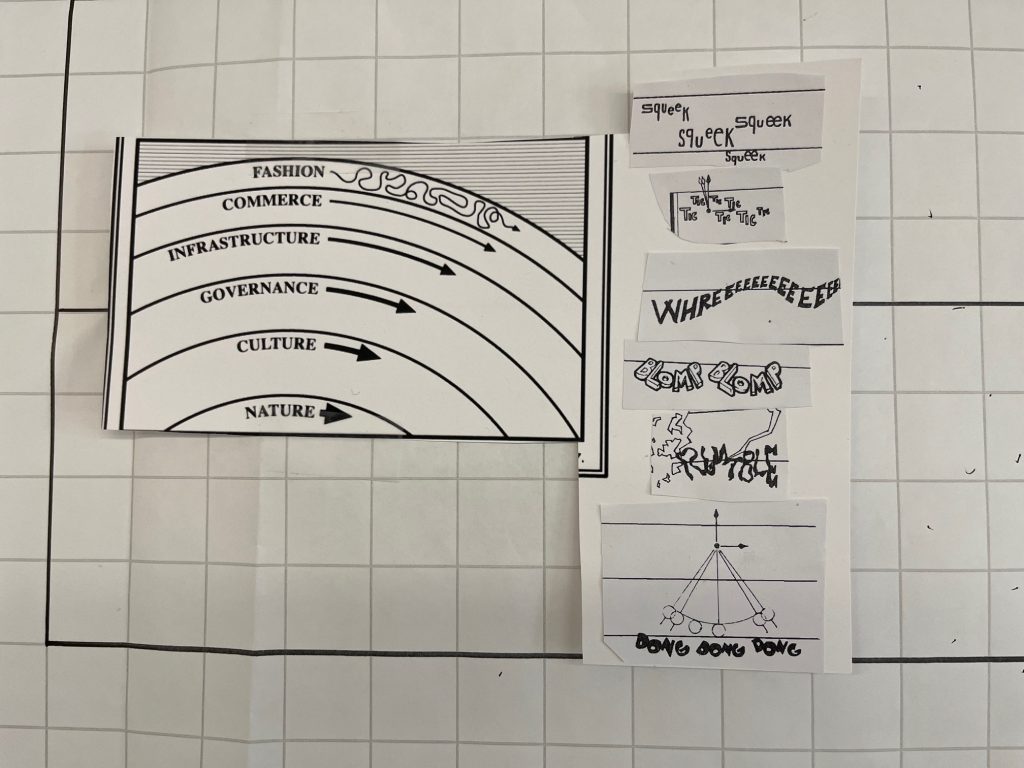

The themes reflected our discussion thus far: a focus on knowledge, experience, time, order/disorder, permanence/impermanence. The forms reflected our shared interests and creative pursuits, and also highlighted the potential importance of the number 21. Sound is a recurring medium of interest, and time was a recurring subject of concern. They both came up in our conversation about duration: different sound-capturing media (vinyl, CDs, cassette, Spotify) are a kind of time-keeper, each with their own distinctive qualities. Finally our discussion of spaces emphasized that our project ought to sit somewhere between fully open (Wawa) and fully closed (anechoic chamber).

What can we make of this cacophony? A few tangible takeaways remain. We want an audience beyond the classroom. We want to use public spaces and the broader Princeton campus. We need you to fill out this survey. We are interested in sound, time, and ephemerality.

I am interested to return to this post 8 weeks from now. Are we already en route to our finished product, or is our ultimate project buried in a footnote of today’s discussion, brushed aside, only to be brought back in a mad scramble in week 11? Only time can reveal.

September 23:

Response (co-written with permission of instructors)

Knowingly. As we arrive, our moving desks demonstrate the materiality and embodiment of knowledge. Knowledge is re-shaped and re-adapted at every class. We move. We make ways to our knowledge needs. New connections are made, and sometimes we can’t quite match the shapes. Throughout the class of September 23rd, knowledge makes a stand as collaborative and creative. Our guest, EHM, seems to point in this direction too.

As a class, we tergiversate at first, slowly approaching this new portal. The objects on the table are Silk almond milk and cataloguing cards from the Library of Congress. Extracting pieces of knowledge. It’s impossible not to think of post-structuralists, Barthes, the shift towards reading objects as texts. Our critical practice moves to everyday artifacts, an ability no one in the classroom can’t seem to turn off. But then. Milk, as defined by dictionary.com, is an “opaque white fluid.” And it hits. Knowledge. Glissant and his opacity.

For Glissant, knowledge involves embracing the “opacities of Being,” and “tremblings of knowledge”. Such opacity respects the complexity and irreducibility of identities and knowledge, opposing demands for transparency or total comprehension. CW uses the expression of the “unquiet brain” to name the critical impulse that refuses leaving things uninterpreted. Almost as if we were all struggling with opacity. As if we have to bring everything to light. Enlighten the world. Make others see. “Are academics more miserable in general?”, someone asks. Knowledge. After all, in the allegory of the cave, the prisoners end up killing the prisoner who’s seen the outside world. KH brings up the question: what does knowledge look like in the wake of experience?

The readings from previous weeks orbit the discussions: experience is mediated by modernity and industrial capitalism (Benjamin, Agamben, Williams); experience is also elusive and necessary for self-reliance (Emerson). hooks and Anzaldúa especially reclaim marginalized (and autochthonous) experiences as sources of knowledge and resistance. Knowledge. Our objects this week are text-heavy, underlining the most widely accepted forms of knowledge-making in modernity. Foucault will remind us that knowledge is produced through power relations and is inseparable from power structures. Truth is politics. Politics is action.

Knowledge: who mediates it? Some members of HUM 583 are instructors; all of us will have to be at some point. Rancière describes the “explicator”, defending the importance of intellectual emancipation, where all share an equal capacity for knowledge. Explicators control the process of understanding by deciding when and how knowledge is explained. Students become, thus, “recipients of knowledge.” But is such a hierarchy sustainable? Knowledge. Explicators sustain an education system that only exists to maintain learning spaces — a sort of bookish pyramid scheme, if we will.

What’s the difference between a teacher, a mentor, a coach – or even a curator? We reach knowledge as emancipation. Instead of the pyramid, knowledge takes the shape of the rhizome for Deleuze and Guattari. Of course, this echoes some Hartman – also Rancière, Glissant, Weil. But let’s stick to Hartman. For Hartman, the knowledge of girls like Esther Brown is part of a network of affect, embodiment, and resistance, all of which are epistemic. A construction of knowledge that the author herself is part of in her act of critical fabulation. Rancière arcs to Hartman in learning as collaborative. As a class, we do not make it to Lorde’s text, but this feels like the next connection in our rhizome.

Knowledge is better built through the horizontal collective. The first question our guest, EHM, gets is “how do you get 15 academics to agree on anything?”. Twitter wars aside, she reveals that what brought a group of head-clashing, musical humans together was sitting down and making things. Literally. From an initial disagreement rose the beginnings of a cross-cultural, collaboratively produced research framework. Before people started working together, the workshop was a disaster, with screaming, crying, and – worst of all – theorizing. EHM urged a shift from abstraction to practice, from theorizing knowledge to doing: performing, writing, and experimenting across disciplinary boundaries. EHM points to the plasticity of music – from music cognition to ethnomusicology – as a field, a generative site resisting containment within a single method.

In May 2025, EHM was awarded a Graduate Mentoring Award, to which she self-deprecatingly blamed “luck”, but also an ability to listen to students. Good mentorship is not as prescribing or explicating, which would echo Rancière. It is a matter of flexibility, attentiveness, and responsiveness — listening carefully to what students (and colleagues) need and helping them succeed in multiple possible futures. IH brought up Haraway’s “situated knowledges” and the need to see from many angles, wondering if this role of the mentor could be transferred from Haraway’s visual metaphor to the aural realm. Towards a multiplicitous hearing that, much like Hartman’s chorus of riotous girls, pivots not on learning to see differently, but rather on learning to listen differently; in short, as EHM remarks, “figuring out where someone is coming from”.

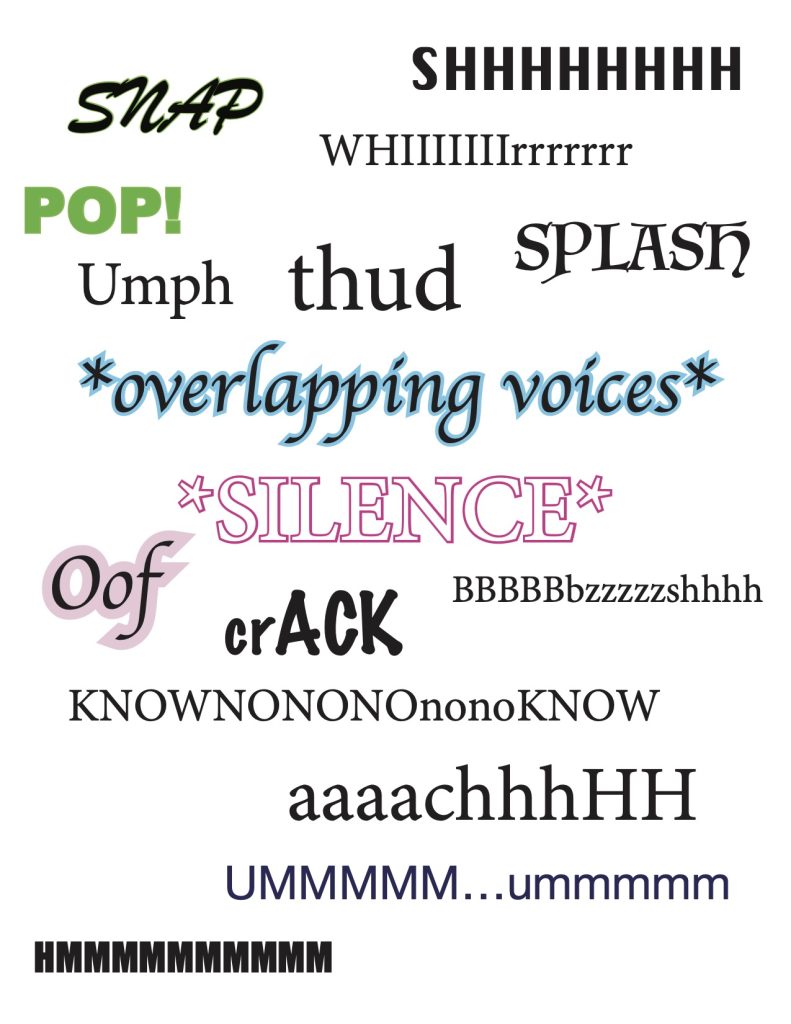

A lot of EHM’s praxis matched many of the ideas we’d discussed, of horizontal and collaborative knowledge. Not only that, however, EHM encouraged us to attempt, to be productively wrong, to cross bridges. Maybe knowledge doesn’t have to be exclusively text-heavy. IH and LDVG decide, then, to try (essayer) something of their own. Instead of simply writing, we make a soundscape, reflective of some of the “knowledge” and “experience” gained so far.

The soundscape can be accessed here:

Soundscape acknowledgements:

Ambient Crescendo 001B by nlux — https://freesound.org/s/620790/ — License: Attribution 4.0

no_child_slow.wav by xpoki — https://freesound.org/s/436749/ — License: Attribution 3.0

Baby Laughs, VariousS PE144601 by gumballworld — https://freesound.org/s/398549/ — License: Attribution NonCommercial 4.0

The Office by qubodup — https://freesound.org/s/211945/ — License: Attribution 4.0

drunks fighting.aif by tigersound — https://freesound.org/s/15559/ — License: Attribution NonCommercial 4.0

acoustic guitar melody #011 by GuitarStringTheory — https://freesound.org/s/735192/ — License: Attribution 4.0

SweepInMMV1_3.wav Blur1.wav by MikeOscarFoxtrot — https://freesound.org/s/484402/ — License: Attribution 4.0

September 30:

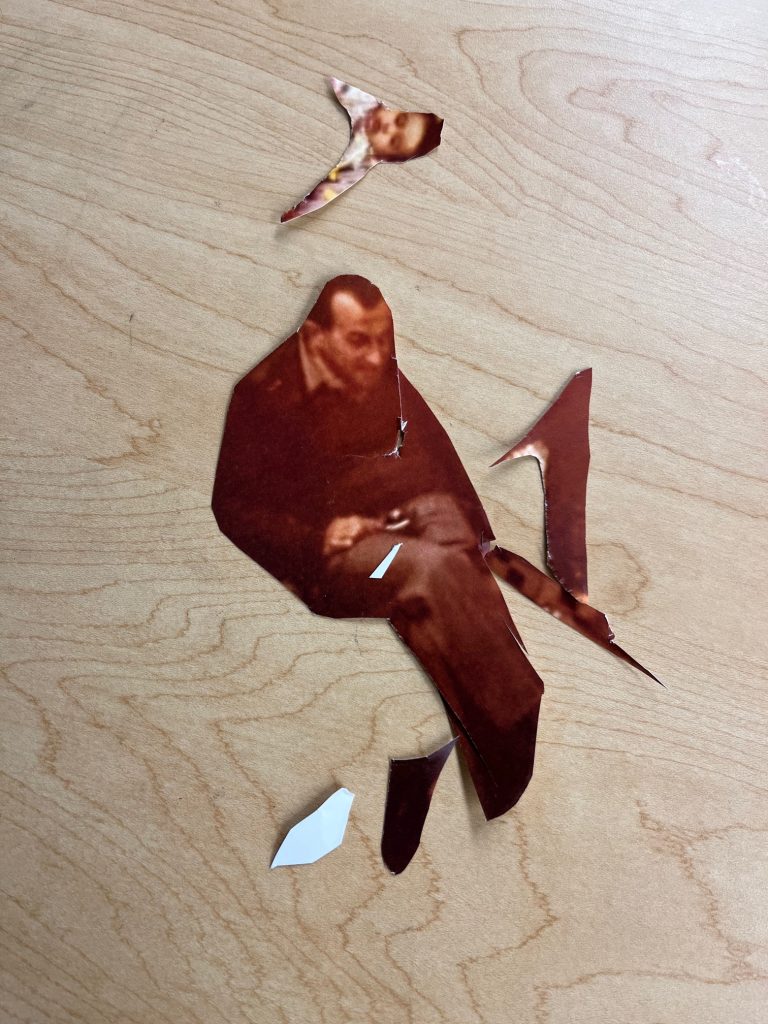

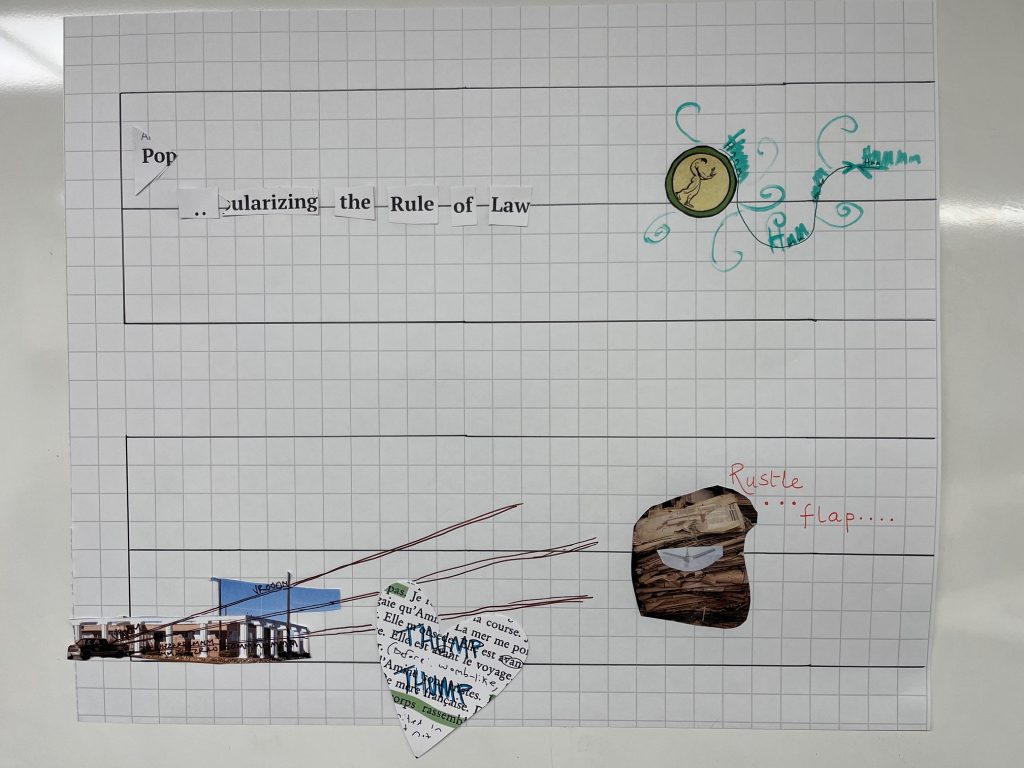

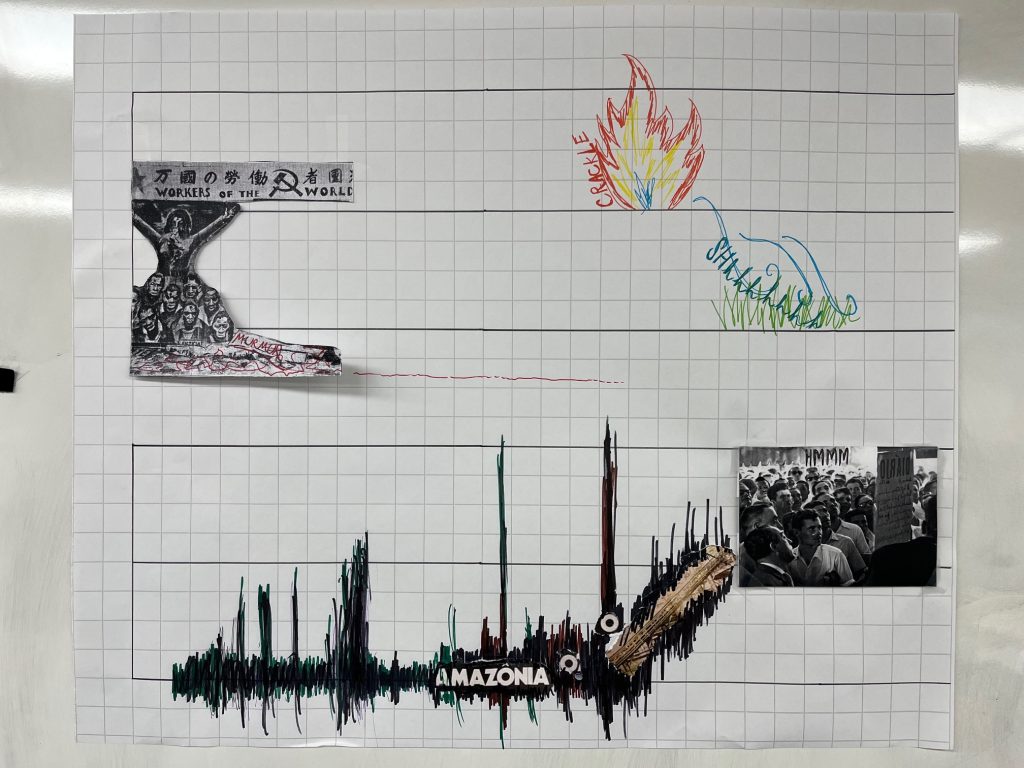

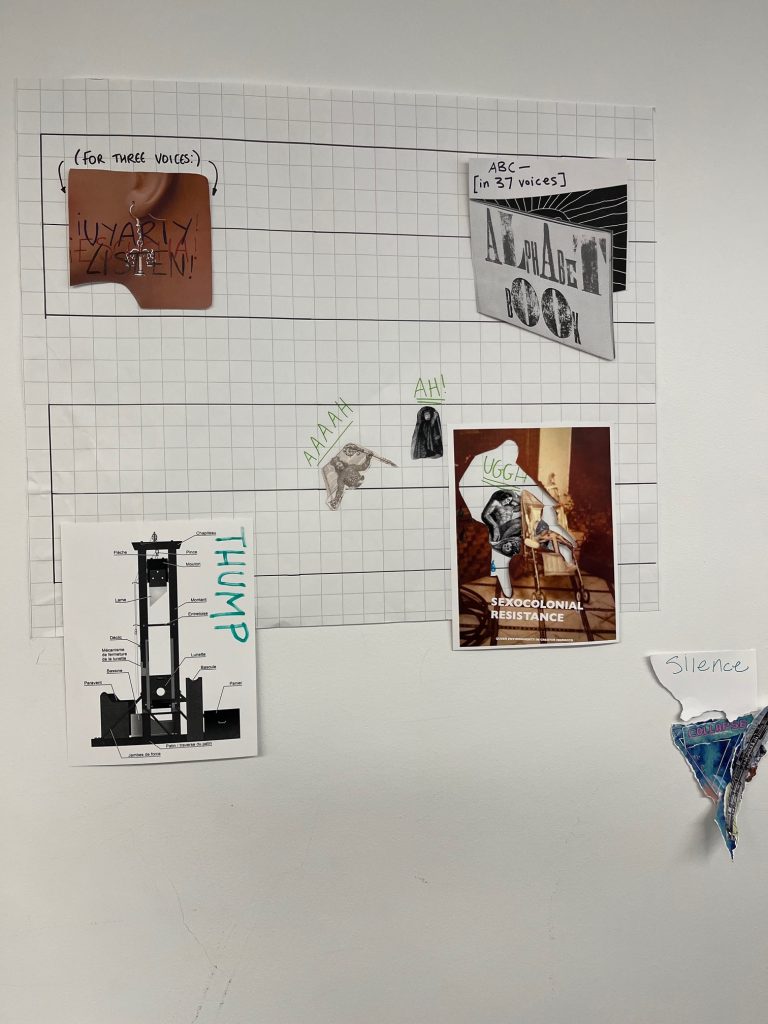

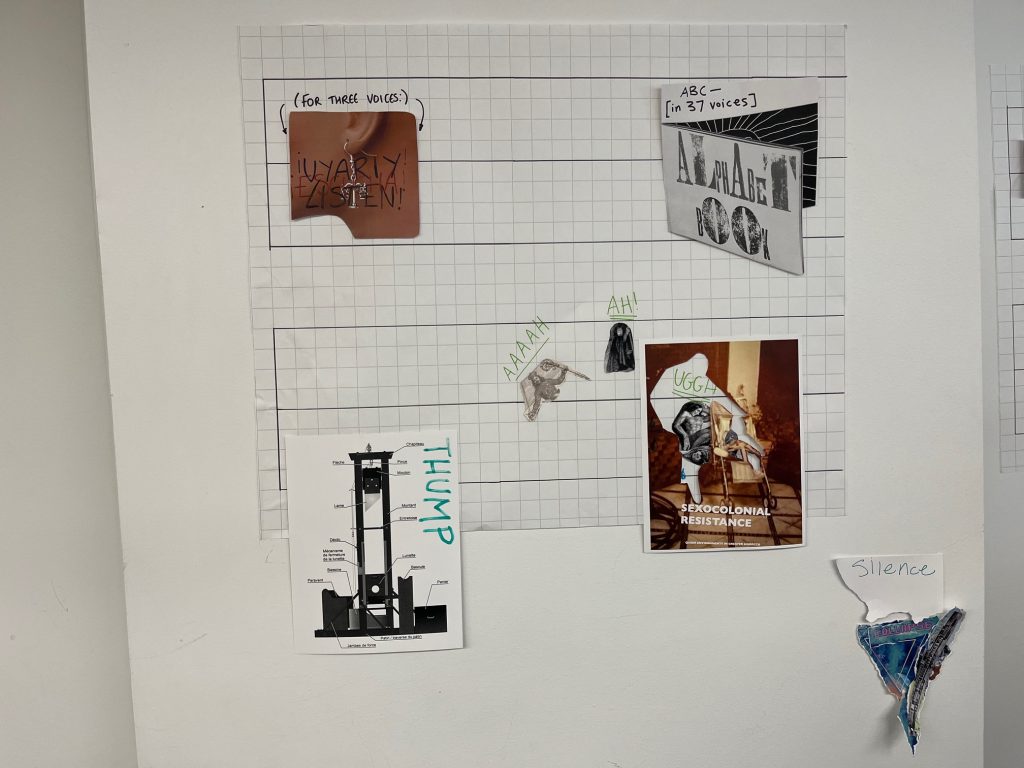

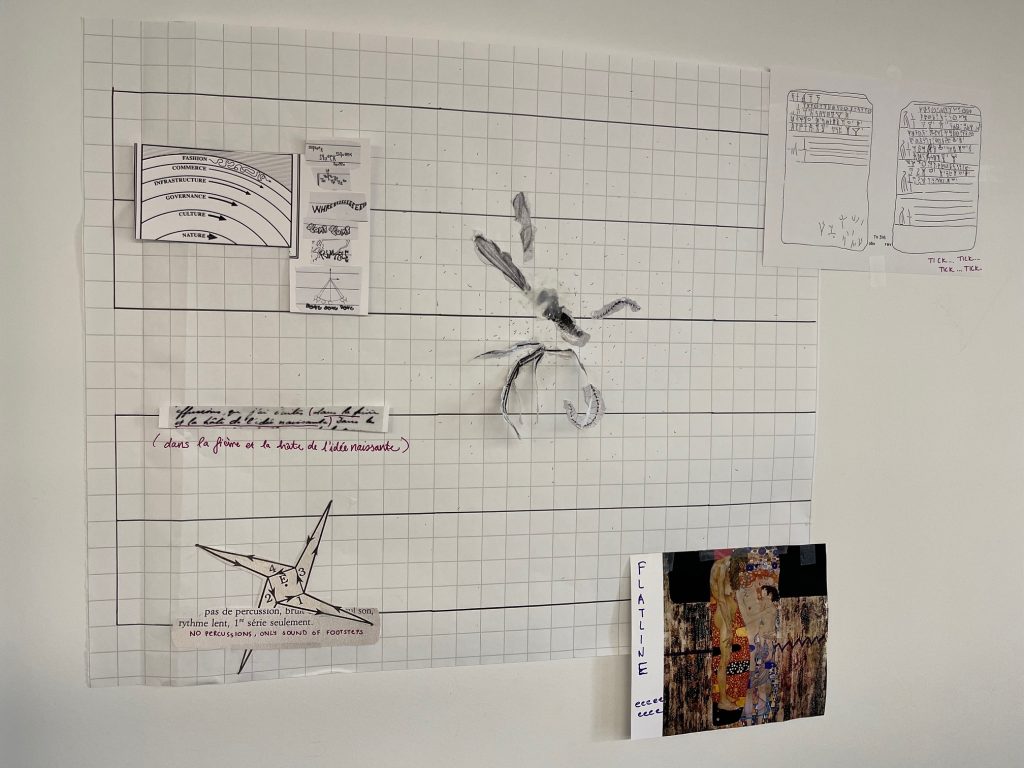

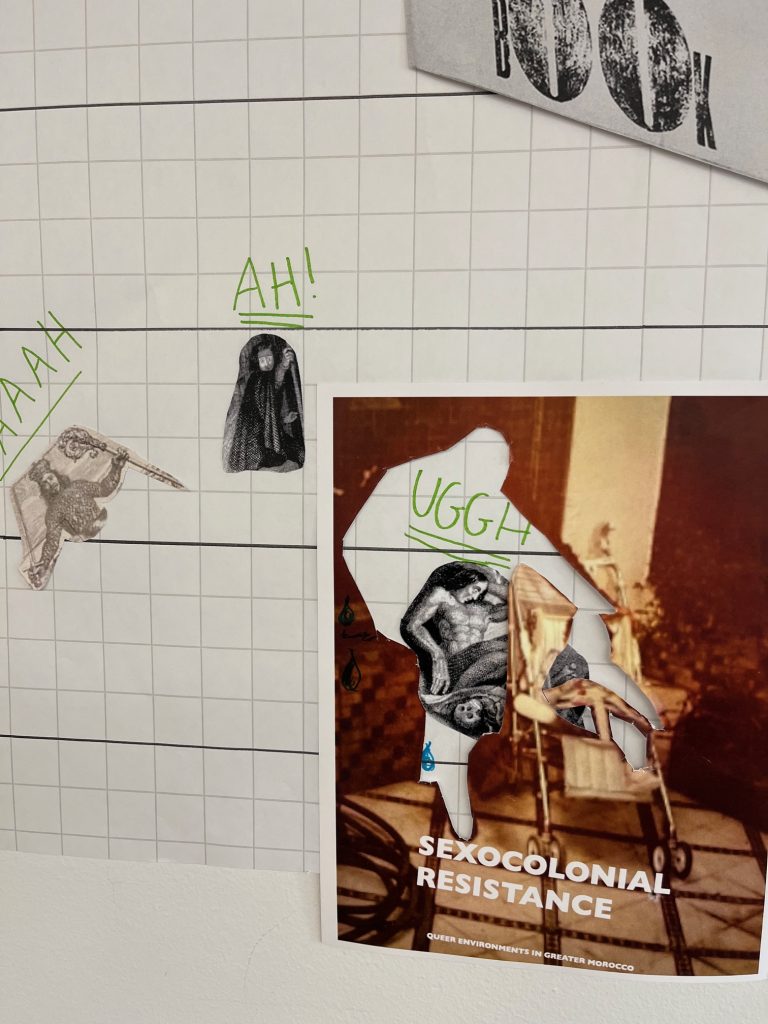

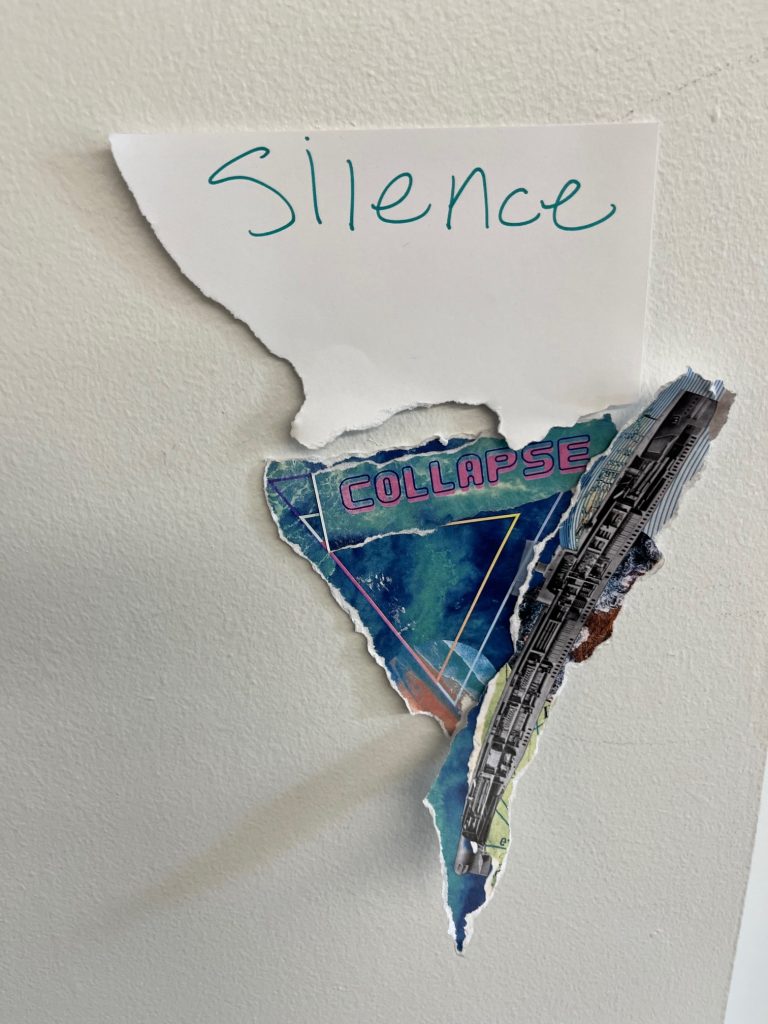

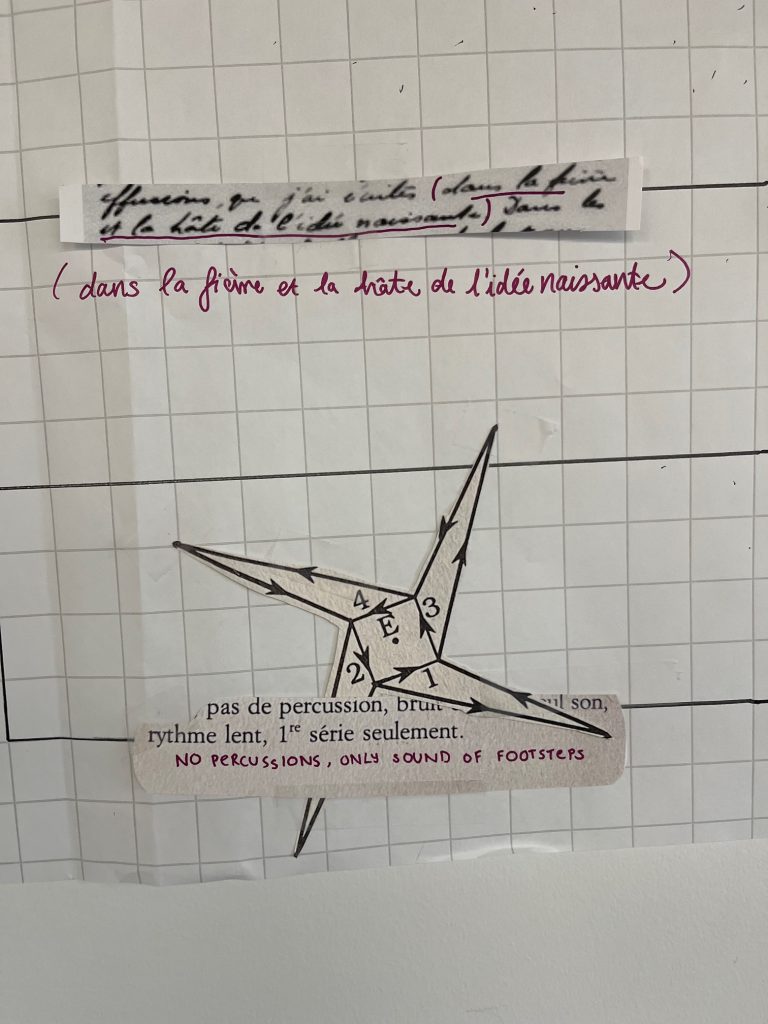

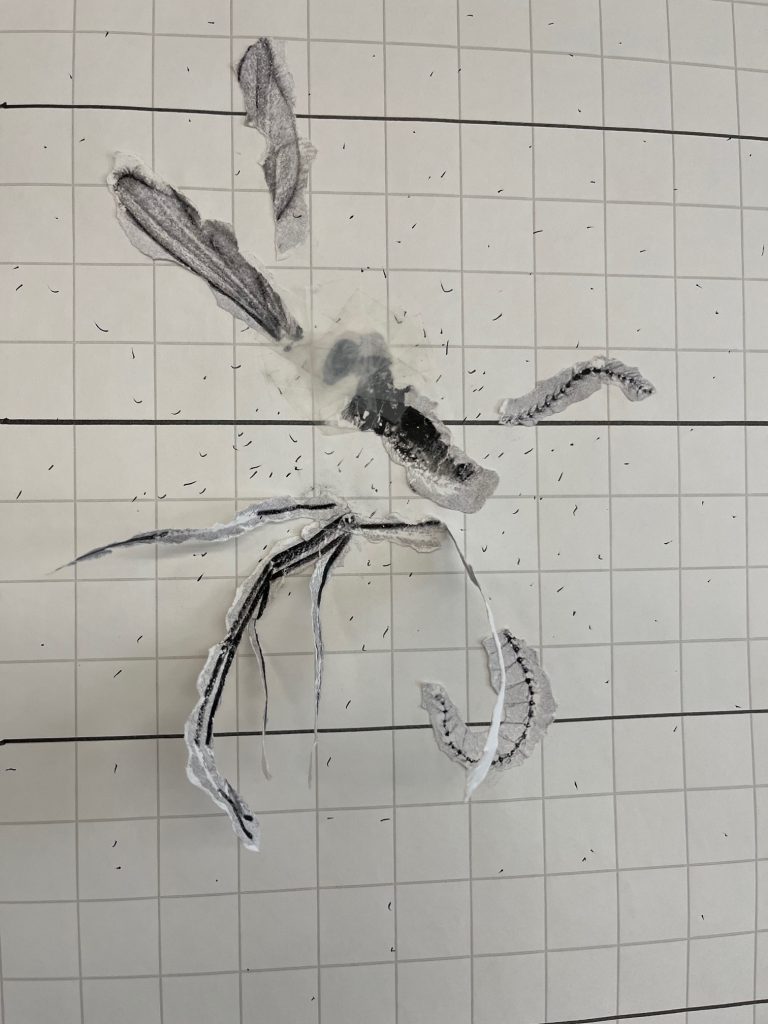

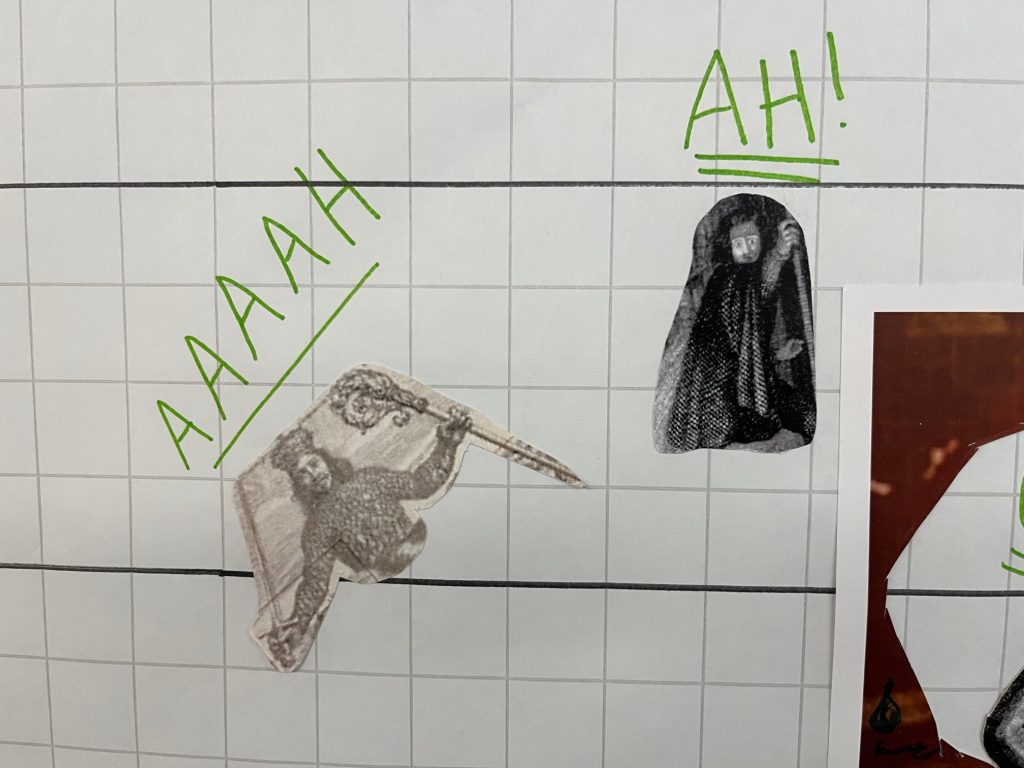

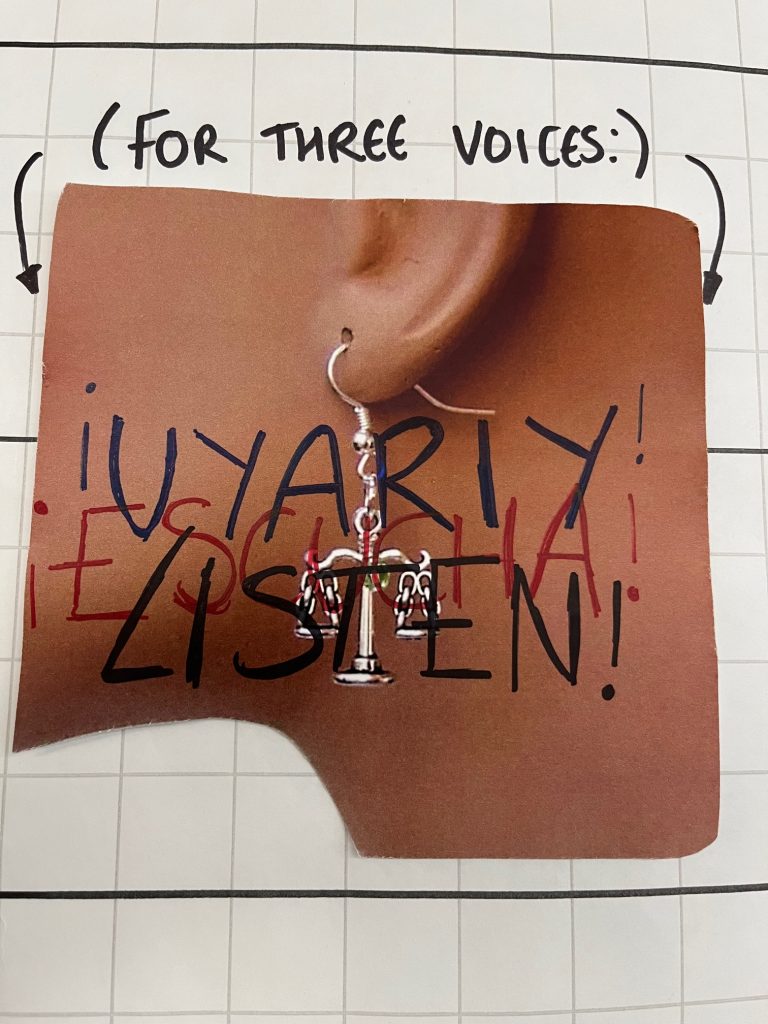

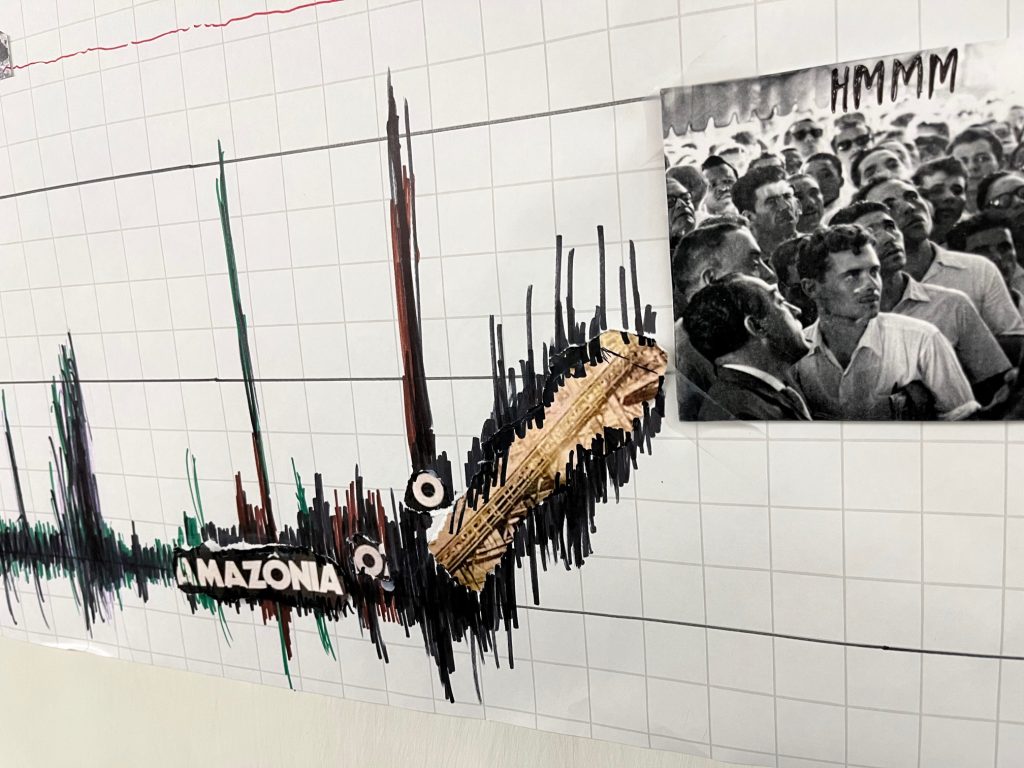

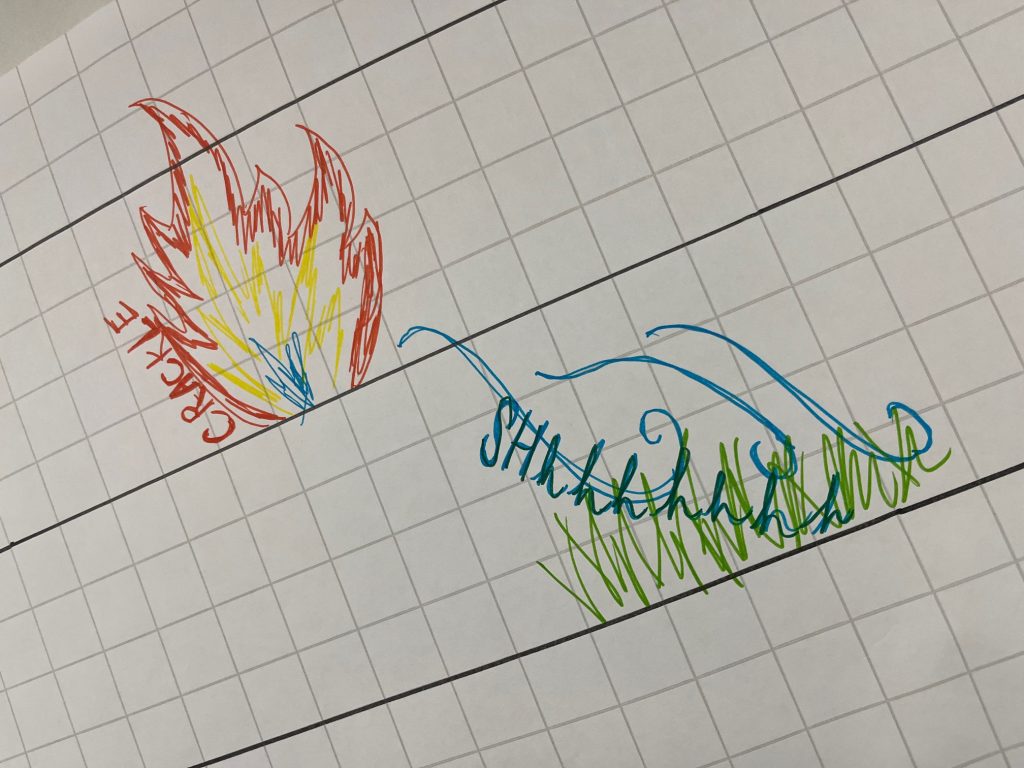

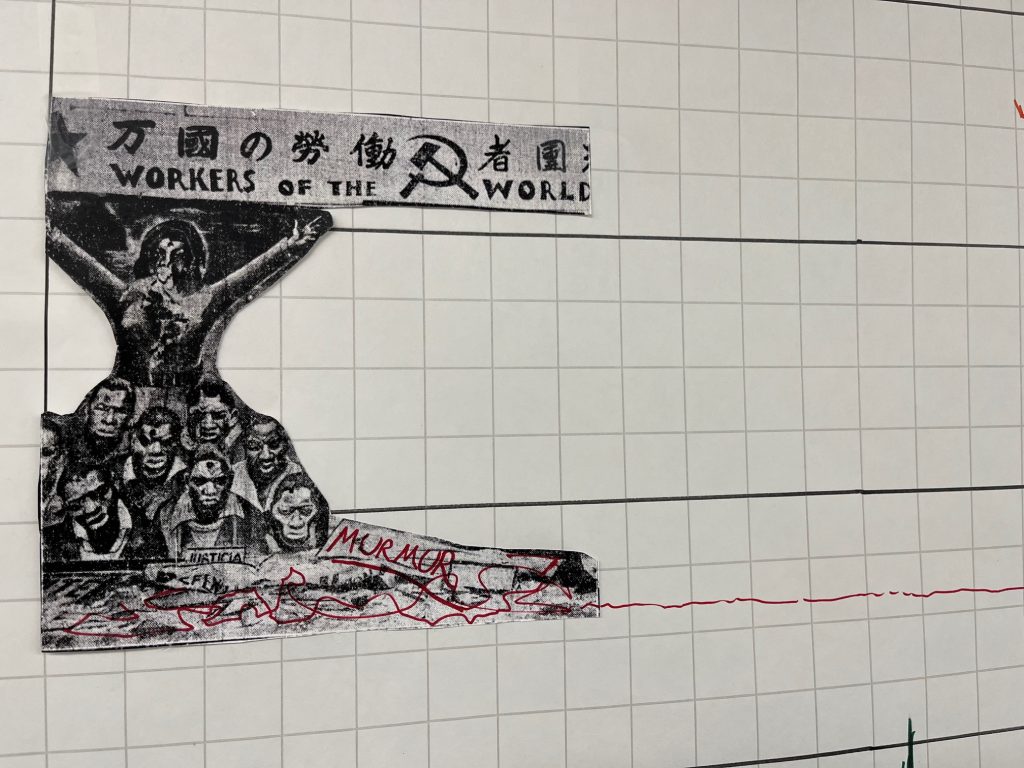

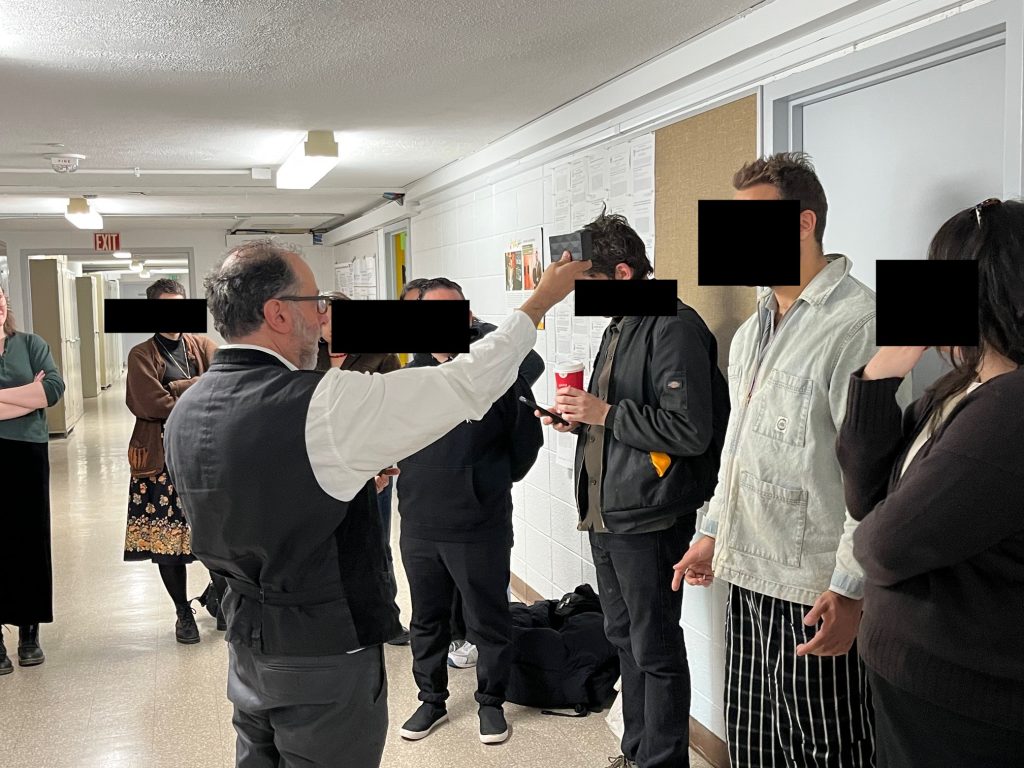

Before our guest’s arrival, KN orchestrated an activity based on Cathy Berberian’s Stripsody (1966), which converted components of comic strips into a musical score. We did something similar with images related to our research. Scenes from our activity:

Then our guest JW shared haunting background stories from his project The Batture Ritual (2018).

Response #1

“You’re all listening to each other, whether you know it or not.” This is what KN remarked after folks shared graphics they deemed representative (in one way or another) of their research.

A common feature of graduate school, and of academia more generally: we are frequently asked to describe our research, and we often do so—in fact, we are expected to do so—in the most individual terms. Our pronouns are singular. Our agendas, ideally, one of a kind. The fiction: our work is entirely self-generated.

Over the course of a month, and in the inter- and anti-disciplinary environment of our class, KN posits, we have changed the script. We have shaped each other’s methodologies and concerns. And we have, at least for the time being, begun to shed the fiction of isolated research.

…

In an act of extended listening, which is also, necessarily, seeing—given the graphic nature of our presentations of our renewed research agendas—I have experimented, admittedly inexpertly, with the medium of JG’s graphic: the collage. In my case, I have created six digital collages intended to place together related themes from the disparate graphics individuals presented. These collages are unskilled (made on PowerPoint—indicative of the limited extent of my technological expertise), a little silly at times, and, most importantly, inexhaustive. Nevertheless, it is my hope that these imperfect collages serve as a kind of subjective, incomplete synthesis of emerging themes and connections. The collage—in the most general sense—struck me as a fitting medium, because it is, by definition, a grouping of things, which, though different (and maybe even discordant), can nevertheless be placed together. The collages are meant to maintain the heterogeneity of our projects and interests, while, nevertheless, attending to the ways in which they intersect, and the ways in which, in this environment, we have begun to listen to each other.

…

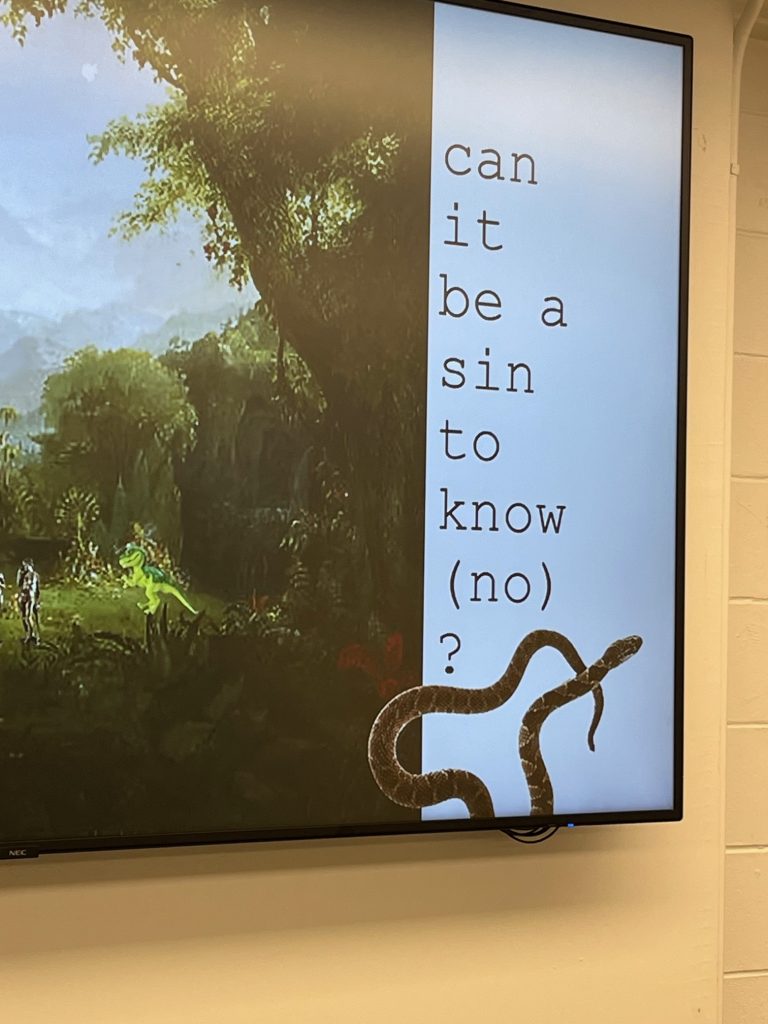

Collage 1: can it be a sin to know (no)?

In Thomas Cole’s “The Garden of Eden,” we find what we might expect: Adam and Eve and forbidden fruit. But we also find a dinosaur figurine, the same proportions as the first man and woman. And the fruits appear to be apples, which are historically inaccurate. Even more out of place: the Apple logo lurking in the sky like a capitalist cloud. This collage references the objects presented at the beginning of class: LE’s lucky dinosaur figurine, purchased at an art supply store that catered to art students and figurine enthusiasts, and ME’s freshly picked apple with a bite missing. The dinosaur was dwarfed by the apple; it looked like he may have had to nibble for days to make a dent in its flesh. Those familiar with the scriptural account of Genesis will know that the tempting serpent originally had legs, and that his divine punishment for his involvement in what later became known as “original sin” was to slither on the ground instead of walking on legs. The title of the collage is a modification of Satan’s question in Milton’s Paradise Lost; it references the aural play on words central to LDVG and IH’s soundscape, the phonic negation (no) contained in knowing. And it also anticipates Satan’s answer to his question: Can it be a sin to know? No.

Collage 2: archive / document / duty / listen

Many of our projects require at least methodological engagement with the archive (in both narrow and general senses). DA described her early experiences with book history by presenting a picture of an alphabet book that enabled her to explore the intersection of education and colonialism, and prompted her to think about children as knowledge producers; HF presented a photo of countless archival documents maintained in precarious conditions; NP shared a photo of an archival letter intertextually describing Renée Vivien’s approach to writing poetry; and, by offering a reading of a tablet written in Linear B that frequently references human sacrifice, AR articulated the ethical demand of the past. Others discussed published materials such as magazines (EB and LDVG), newspapers (NI), and books (CW and ME), as well as works of art (SD) and juridical proceedings (IH), which are often archived. The collated images are intended to portray the archival impulse as a form of listening to the past—but an interested one, one which is tied up with and inextricable from power (ahem, Foucault). The etching of the Library of Alexandria intimates the impermanence of the archive—its inevitable destruction—anticipating the Derridian allusion in collage 5.

This collage is also self-reflexive: what is the purpose of the archive of our class? Where does the impulse to archive come from? How is our archive flawed? The floating Apple logo is intended to gesture towards the words I type on my computer, anticipating their inclusion in our class’s archive.

Collage 3: sovereignty / colony / colonnade

The background image is inspired by the architectural aesthetics of the legal brothel in Nevada that inspired LE’s research. This collage draws on numerous participants’ references to colonialism—both its practices, but also its aesthetics (DA, LDVG, SPT, IH, and CW)—as well as spectacles of sovereignty more generally (CW and ME). The images on the right side of the collage intimate the ways in which practices of collection and expansion can, themselves, be colonial. The catfish and the bottle fly, featured in JW’s artwork (EC also presented an image of an insect), allude to hierarchies among human beings and species (the “great chain of being”), as well as the parasitic nature of power. The fly, in particular, anticipates the scenes of decay in collage 5.

Collage 4: fragmentary / incomplete / silent / violent

This collage brings to the fore the exclusions and violences of the archive, already intimated in the previous collages. A number of participants presented graphics that represent their research on historical violence and archival exclusions, including but not limited to the spectacular violence of the guillotine (CW), the Brazilian celebration of the domination of the Amazon (LDVG), state-sponsored violence (NI: police violence), and imperfect juridical efforts to account for this violence (IH). CW translated a passage from Nina Bouraoui’s Tomboy, conveying the author’s sentiment: “We don’t exist. People don’t look at us.” CW identified Tomboy and texts like it, depicting hybrid human existences, as “calling out to be studied,” just like the Linear B tablet, which AR described as a “last plea to history to keep” its subjects “alive.”

Collage 5: decay

As already discussed, HF described the precarity of the archives; more generally, others referenced human mortality (NP, CW, AR) and climate change, which has already wrought, and will continue to bring, devastation, including the destruction of archives (LDVG). This collage depicts the burning of the Library of Alexandria, juxtaposed with a forest fire caused by climate change. LDVG alluded to ecofeminist resistance to such destruction, which requires the recognition of the interconnectivity of injustices, including speciesism, racism, colonialism, and misogyny.

Collage 6: womb / tomb

Almond milk: SD’s recurring symbol for the mother-child connection, and its negation. This collage grapples with the maternal metaphors many male artists employ to describe their work (see Nietzsche and Joyce on giving birth to their writings), juxtaposed with the systemic denial of women’s corporeal, political, and creative agency. The womb’s creative and negating capacities are alluded to with Frankenstein’s ghastly effort to create life without a womb; the ancient pregnant sculptures that are now missing heads, bringing to mind the recurring motif of the guillotine; and Mary’s loss of her son (reminiscent of AR’s discussion of human sacrifice in the ancient context).

…

With our disparate images and themes, we composed a series of sounds in the style of Cathy Berberian, an endeavor which endows us with another way to listen to each other. I hope that the collages I have made contribute to that objective: of admittedly imperfect listening.

Response#2

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1656): peasants rest on the harvested field. To the right, in front of the field of uncut wheat, another man reaps the fields with a scythe at hand. The eye travels along this painting, indiscriminate: horse-drawn carts in the distance, a church, the harbor in the distance. We can see this ‘primary economy’ weaved (and weaving) into the foreground, as the eye travels and curves through the depth of the landscape, to the harbor, hinting at a broader, global economic system. It is this scene depicting the cycle of 16th century Dutch agrarian economy that artist JW, today’s IHUM visitor, reveals as one of his primary sources of inspiration for his ‘Batture Ritual’, his film of the batture in New Orleans. ‘Batture’ is a creole term designating the land between the shore of the Mississippi and the levee––an ‘interstitial’ (a term JW himself uses), unpoliced space, characterised by its impermanence, contingency, its liability and danger––as well being as the fastest land mass disappearance in the world due to climate change. JW explains that the people in the film are primarily grey market catfish sellers, set against the backdrop of the world economy in the river delta: large cargo ships pass by in the distance, diesel engines roaring. The batture is a prominent part of New Orleans’ history, and yet it is difficult to access, and even see—somehow, it is this invisible space that JW renders visible.

LDVG’s and IH’s soundscape (see previous post)––relating know to its homophonic no––set the tone for JW’s introduction. He claims that his modes of research are flipped around, with the desire to ‘empty [him]self of everything [he] know[s] about photography and Louisiana’. In this manner, the ‘no’, becomes generative, in its resistance to epistemic preconceptions: you enter in a stance of not-knowing, which, interestingly, leads to a state of reacting––you can apply the intellect later, JW claims. I was struck by JW’s contrasting use of reacting to knowing. I wonder to what extent you can divorce yourself from previously acquired knowledge, especially in art—is there not a component that is akin to muscle memory? If that is the case, how can we listen to our gut; how can we let ourselves be more moved by beauty? Should we have to divorce the emotional from the intellect? (maybe it would be interesting to think about with e.g. Kant, Hume, Nietzsche…)

In the ‘Batture Ritual’, the tree is at the center of the frame, container ships visible from afar and audible, people slipping into the scene, wading in the waters. This tree becomes a formal device that can divide the frame, and subvert the foreground-middle ground-background distinction. What also caught my attention was although JW described the creation of a formalrelationship with the tree, what first drew JW to photograph it was how he was ‘moved’––the beauty of the scene.

I also noticed how JW described his photography in such a theatrical manner—the picture of the fish carcass was ‘orchestrated’; the tree became a ‘stage’. Moreover, JW said that because of the vantage point’s ‘neutrality’ (an effect created by the height, the batture being 16-17 feet above the river) you come out of it with a ‘certain knowledge’. This knowledge is, of course, constructed, choreographed, and composed—how can we square the initial, intangible instinct that draws one to create with the staging of objectivity as a form of knowledge?

Moving forward: JW spoke about his use of sound, and how important sound was in his film. He, in fact, sectioned the soundscape into parts, and separated it from the visual, also editing sounds through ‘spectral analysis’.

October 7:

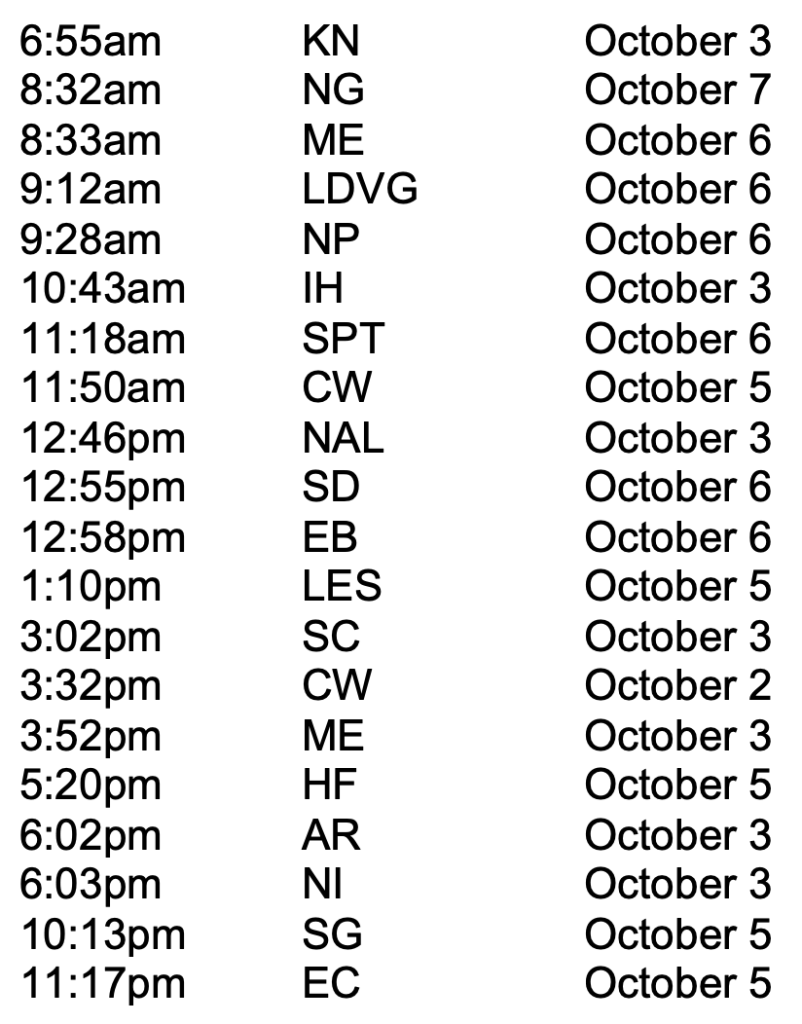

First order of business: the unveiling of our audio experiment PLAZA. The constraints were these:

Unbeknownst to the students, we then ordered these according to the time of day which they were recorded, which simulated the sounds of the plaza from morning to night. It sounded like this:

We celebrated LS’s passing of generals and sent SPT off to his in great style:

And ME’s collage came alive, the snake reaching from the world of the image into real life.

SC+JG made a few magical artifacts. A newspaper – The Disciplinary Enquirer – that reports breathlessly on the breaking news of our seminar:

And a podcast summing up the first half of our semester:

October 14: FALL BREAK

October 21:

Response #1 (HF): “Fields, Fears, and Forests”

We returned from break, welcoming fall foliage, sweater weather, and tales of rollercoaster rides and visits to family. As per tradition, we started by discussing the objects brought to class. Representative of geographies, movement, and itineraries of travel, the zines and Paddington by NI and IH invited us to think about community and the process of care giving. KN brought another “university packet” to accompany our readings for this new unit—a collection of our peers’ assessments of their field and how that maps onto the graduate school structure at Princeton. What does it mean when your field is at odds with your department? Who are we in conversation with? What does belonging to an academic discipline/field/department/program look like?

CW noticed how our field notes revealed an anxious subject and the ways in which our uncertainties, emotion, and affect was at display in these write ups. KN reminded us that this exercise, like our stab at Cathy Berberian’s Stripsody (1966), is an opportunity to reintroduce ourselves to each other. The AWS outage resulted in two different prompts and submission methods for this activity which created interpretive differences amongst students and their invocation of the personal subject in their responses. After contemplating the generational differences in how people position themselves in their field, we turned to our reading for this week.

Thinking with Thomas Bender and Bill Readings, we talked about the rise of the American research university and how, during the Cold War years, the university became the site of a marriage between statecraft and knowledge production (KN). Despite the rise of new departments like ethnic studies, gender studies, or African American/Black studies, the university evaluates the intellectual output of its faculty through the “scientific model” of the Cold War era. Holding onto this thread of evaluation, KN and CW explained the tenure review process and AR noted how the need for letters of recommendation in tenure files produces a compounding penalty against underdeveloped fields in which a relatively small pool of people will be required to do this labour routinely. N-AL added how the university structure obfuscates the asymmetrical labour undertaken by graduate students, graduate workers, and graduate research assistants. Knowledge production in the academy involves a host of unaccounted forms and relations of labour. CW linked this to the ongoing push to make the university more administrative through the excessive use of emails and other forms of labour that are not teaching, writing, or doing research. AR urged us to view departments as more than intellectual environments. University departments are also material and historical artifacts that have an insurgent value due to the possibility of student-led protest and occupation of these spaces. This reminded me of Readings statement on institutional pragmatism. He writes, “Such a pragmatism, I shall argue, requires that we accept that the modern university is a ruined institution. Those ruins must not be the object of a romantic nostalgia for a lost wholeness but the site of an attempt to transvalue the fact that the university no longer inhabits a continuous history of progress, of the progressive revelation of a unifying Idea” (480).

We reconvened to talk with our guest RPH about Descartes, his Discourse on Method, and the use of forests (and walking in a straight line) as metaphor. After listening to SC and JG’s podcast and accompanying issue of The Disciplinary Enquirer, RPH commented on our rhizomatic table and the table as a metaphor for Arendt. In the Human Condition, Arendt writes, “To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time” (52). RPH viewed a creative retrieval of the past as the necessary condition for a future.

We discussed the etymology of the word method which refers to being on the way, travel, or choosing one path over the other. Descartes views the forest as a legacy of the past, it is a forest of confusion, a forest of history, or the forest of historicity. In RPH’s reading, Descartes laments the prehistory before the age of reason even as he is undoubtedly shaped by the very intellectual tradition he seeks to disassemble. RPH memorably called Descartes an architype of the antidisciplinarian. He is critical of the idea that the past is mere ignorance and superstition and therefore, requires repudiation. Through the story of Virgil’s Aeneid, we considered the ways in which Aeneas must journey into the underworld and reckon with the past before forging his future. Continuing this discourse on the importance of the past, RPH commented that students are in constant communion with the dead and that all futures are a product of knowledge transmission which implies an enduring connection to tradition and the past. The modern promise of education is the ability to adopt our intellectual ancestors. Through this process of retrieval, we not only craft genealogies of thought but also arrive at generative spaces of future possibility. This is what happened when Charles Baudelaire translated Edgar Allan Poe into French and inducted him in the tradition of French modernism. We concluded by talking about dollar bills, Virgil, eruptions of reality, ghosts, and the grammar of black futurity.

Response #2 (NI):

Boundaries, borders, limits, and related terms have become motifs of our course. This week, KN and CW’s survey prompted us to reflect on not only what delimits our disciplines, but also what we can say they are within those boundaries. Leafing back through our accumulated responses to the survey, it’s clear that it in some ways, it’s harder to pin down what a discipline is in ways other than saying what it is not.

Necessarily, and vitally, there was clear consensus that one thing the PhD is (or supposed to be) is job training – that our shared enterprise of study, while still tied to each our personal ideals, desires, and spirits, is inextricable from our calculations toward a future life. While some spaces still maintain an air of idealism about graduate studies (in the sense of “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life”), our class was not one, and KN and CW’s thorough descriptions of the tenure process were, despite being terrifying, also somewhat relieving int heir transparency.

KN emphasized the distinctions between discipline, department, and field, which are overlapping territories. A Field is more focused, often more malleable, and extending over the ramparts between Departments, which have a crucial role in reproducing normative expectations around what the Discipline is. Gravity is on the side of the department; it disciplines interdisciplinary projects, and it is a risk of such projects to give in to that pull. KN described a paradox:we are trained to present ourselves in terms of our fields, but at the end of the day hiring is highly informed by the older, staid criteria of the Cold War University. AR invoked our Martha Biondi reading, which highlights another pragmatic reality of departments: scholars in Black studies haven’t fought for departments because they represent a coherent project or method – they fight for it because it is the unit of legitimation, power, and stability within the University.

We also discussed alternatives to the Department model, particularly the “Project” basis found in European universities. Unlike departments, they are not conceived to be eternal – but since almost everyone’s jobs rely on the existence of the project, there’s an incentive to keep it going as long as possible. (I wonder what possibilities might be afforded by a project that accepts a set lifespan.)

Our guest RH brought our attention to the continuity between projected futures and past precedents. He said, “I believe in ghosts at a certain institutional level.” Recourse to tradition is often conservative (a maxim we owe in part to Descartes), but he also brought in the more revolutionary example of Walter Benjamin (specifically the text “The Destructive Character”), whose belief in “creative retrieval” of the past blasts a hole in what today reads in Descartes as presentism. We concluded with ruminations on tense (or moods?), with an exchange between RH and AR about the optative.

October 28:

Collaborative response by LES + SPT

November 4:

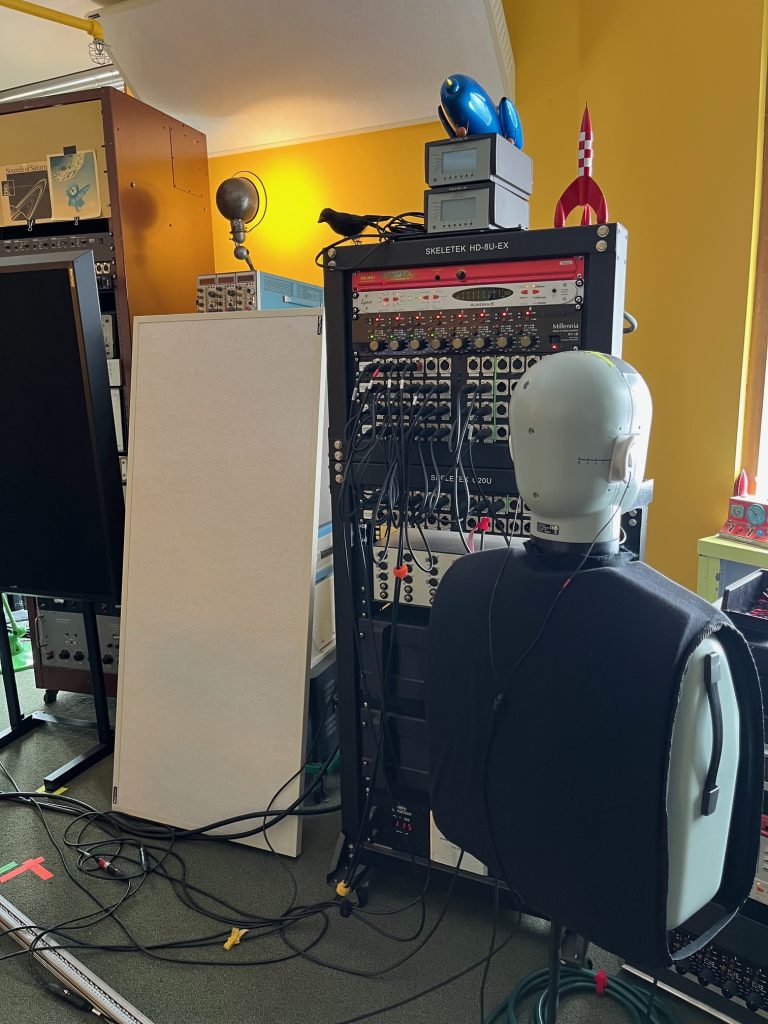

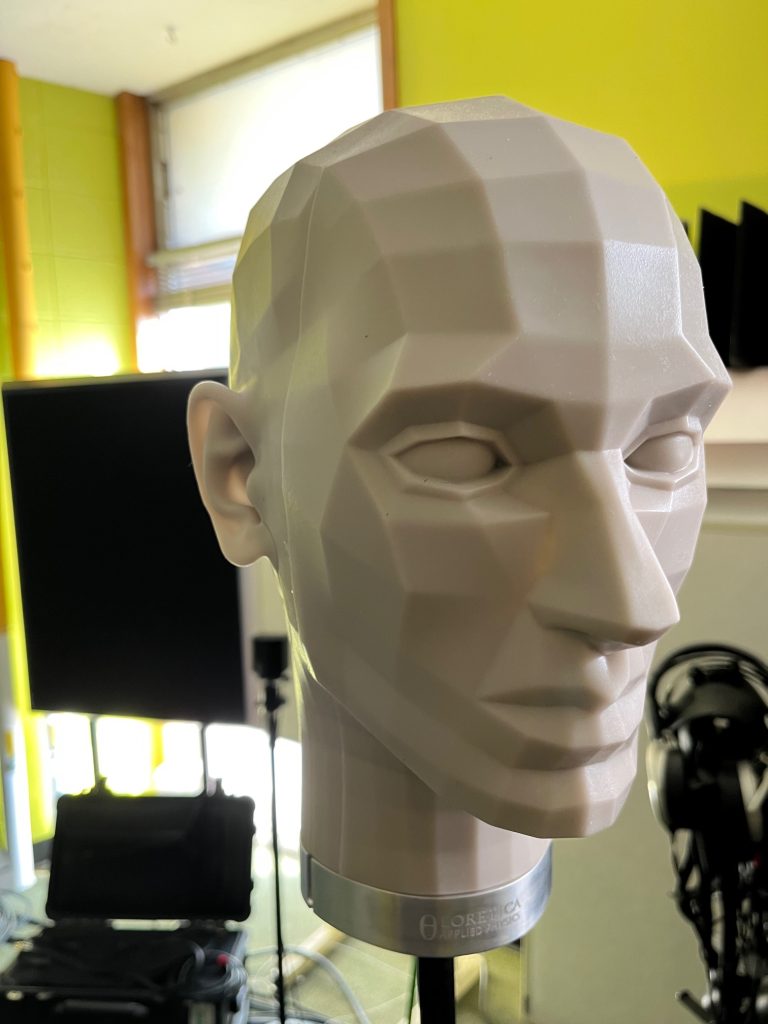

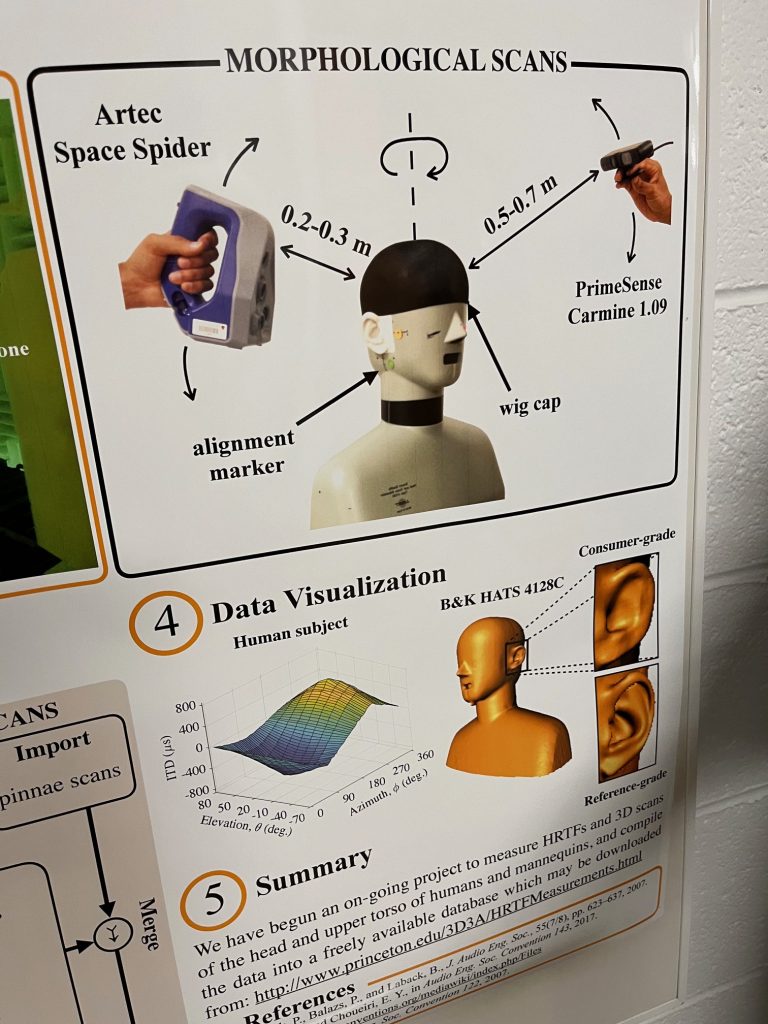

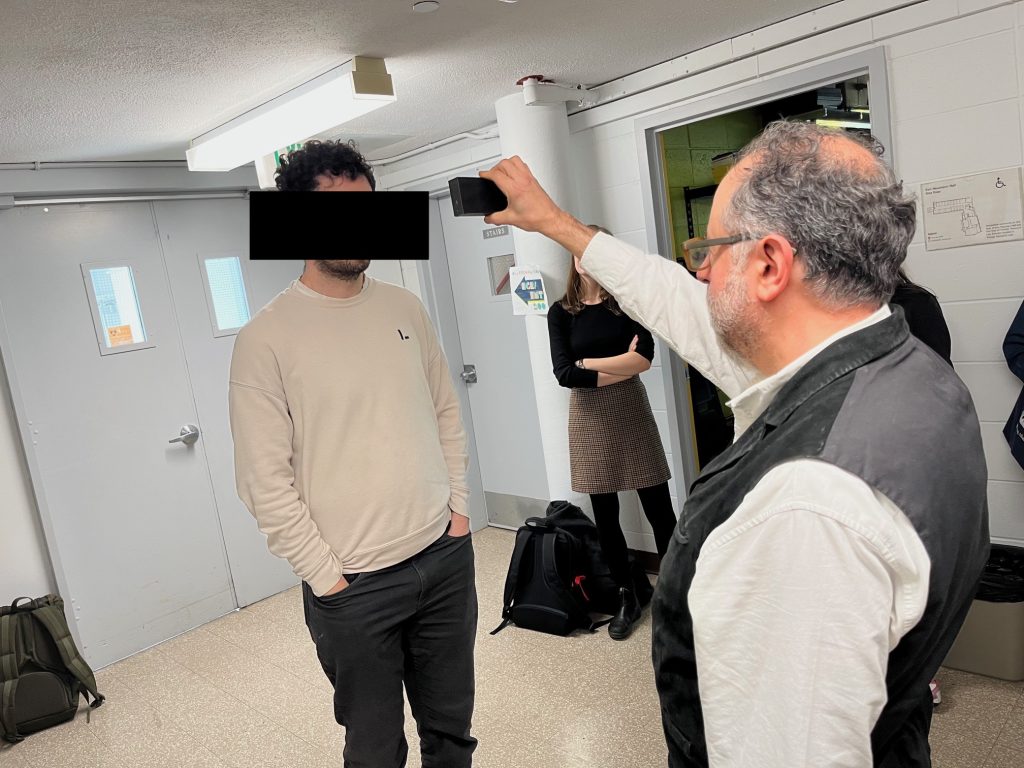

Our session began with a visit to EC’s 3D Audio and Applied Acoustics (3D3A) lab, where we learned about three-dimensional sound.

November 11:

Response #1 (EB):

This week, we gathered in a new place: a shrunken hallway far from our shifting, geometrically ‘open concept’ home of a classroom. It was the far-flung von Neumann Building, surrounded by piles of golden leaves and bordered by a confoundingly steep hill. Our gathering seemed to be one of the few signs of life in the building, with our gaggle of respectfully muted voices bouncing off of walls that seemed unused to the experience. But soon, our guide materialized: EC, manager of the 3D3A lab. Both he and it were our destination, and we readied ourselves for the wonders of the mysterious anechoic chamber.

But first, a demonstration! EC summoned a small, nondescript speaker into his hand. To our eyes, it looked at first to be a simple Bluetooth speaker; but it was so much more. Held before us was a speaker imbued with the mysterious power of BACCH (not the composer!) 3D sound. Some were skeptical; EC described the speaker as shockingly realistic, able to create a full soundscape that fully surrounded the listener when held directly in front of their face. Of course, all were eager to experience this for themselves, and the speaker was slowly passed around. We waited with bated breath as the first volunteer, MJ, held the speaker at eye level, and pressed the two buttons to activate the three dimensional wave.

Live audio on

MJ: “Oh that is SO messed up.”

‘Messed up’ is certainly one way to describe it: as the speaker made its way around the IHUM circle, EC programmed a variety of startling noises to envelop whomever was holding the speaker: a buzzing fly encircling one person’s head, the lighting of an invisible match causing eyes to twitch towards a nonexistent flame, The Beatles seemingly singing directly behind another participant. Each of our perceptions of our aural reality were, quite certainly, “messed up.”

As soon as each of our realities had been rattled, however, it was time to warp them even further by entrance into the anechoic chamber. Room was sparse: only five persons could enter the chamber at a time, and so we waited eagerly for our group to be called and to be ushered in.

“Anechoic, you see, as in the complete absence of echo,” EC quipped as my group entered the office space. We filed, one by one, into the sliver of floor available in the foam-covered chamber. The door remained open, and yet the effect was immediate: EC’s voice suddenly retreated back to hide within him, and the air felt heavy. In spite of the anechoic chamber’s affects being purely sonic, you could feel the lack of sound within the body somehow. It was eerie. It was “messed up.” It was magical.

After we had all taken a turn in the chamber void of echo, the hour had grown late, and we had to make great haste back to our homeworld of taller, freely echoing ceilings; a feature that I no longer took for granted upon returning to our classroom.

The second half of the afternoon seemed almost blurred by the abundance of sound, in contrast to the anechoic chamber’s compression. Two objects were procured, one spread across the room to be discovered and rediscovered at every angle and fold; the other gleamed silver from the center desk in the room. Amongst the words, sentences, and phrases bouncing around our non-insulated walls were

“Equal access to education… but it’s money”

“I like this coin”

“The end of history is illusory”

“It’s meant to be realized as you hold it”

“The Bicho (Critter) itself would have to break in order for us to truly understand it”

“An infinite origami that will never tear”

Suddenly, there was silence. A Vote was held, bringing us closer to the realization of our final project. Then, with the arrival of our guest, PK, the cacophony once again began with a distinct video game theme:

“Not sure if something new is to be found…”

“One thing I run into with game studies is if what is given to you makes something new, or if you just do the predictable path of finding A and B”

“By putting everything in a similar scale, you can make what is important unimportant”

“Every medium has this; the person who is interacting with the object disappears and the game becomes real. Both a joyful and horrific image.”

“Immersion without mimesis… you can completely immerse yourself in a game even if it doesn’t look like the thing”

“Digital twinning is almost like magical thinking”

“The machine is completely working and doing things, but the human is completely taken out of it… this is the environmental mode in games”

We spoke with PK of Galloway, of his bookGaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture(2006), as well as his own work within the emergent field of video game studies, what he called a study of “a canonical work with a very non-canonical method.” The echoes began once more:

“It’s not coincidental that he chose these people… ‘I’m like Deleuze but I’m not Deleuze…'”

“Galloway once gave a 20 minute talk in 70 minutes… he stretched it by going as he does here: concept by concept, word by word…”

“He is using all these other fields to legitimize his claims…”

“Galloway reads like a manifesto”

Then, in a final swell, PK told of his own practical realities of studying video games within academia; the pros and cons, the successes and failures. He remarked upon how “opaque” of a medium video games are to approach: unlike film or literature, the basic mechanics of video games — CODING, HACKING, and the like — often evade the scholars that write about them.

“You can’t read the object hiding behind the little man on the screen.”

Response #2 (SD):

The extremely anticipated visit to the Anechoic chamber was a surreal experience, or, as some colleagues would point out, it was messed up! The interior of the 3D3A lab was quite different from anything we, as students of humanities and social sciences, had ever seen. The presence of mannequins used to run trials, accompanied by a lot of sound-related equipment, made it all the more fascinating. The anechoic chamber, on the other hand, was a very tiny space dominated by green lights. Upon asking, ED responded that the color ostensibly emits positive energy because people can get stressed inside the chamber, so the green light, which has never been turned OFF since the chamber was built, is there to make them feel better.

The second part of the class started in the usual traditional setting, with two people presenting their objects, a coin from Ecuador and the Brazilian critter Bicho, which raised interesting points for conversation to the point that our guest lecturer, PK, observing closely, spilled Coca-Cola on the table!!!

PK started the discussion by asking a subtle question: Do these different combinations give you something new, or do you just combine A and B? He affirmed that they do indeed produce something different. From texts to material objects to sounds, we have moved across scales. SPT asked about the use of space in video games, noting that players constantly construct and navigate environments that act as archives of knowledge and experience. This led to a broader discussion on how video games transform 3D spaces into 2D representations and vice versa, similar to the moment in Poltergeist when the screen becomes a bridge between reality and fantasy. The class reflected on how different media, especially games, produce the aesthetic of losing oneself through feedback, collaboration, and realism, highlighting immersion as a central feature of the gaming experience.

The discussion then shifted to the texts we read. PK asked why Alexander R. Galloway quotes Deleuze and Derrida. CW noted that the author goes slowly, word by word, making the essay very definitional. He tries to come up independently and resists rejecting other media studies entirely. PK added that this is a rhetorical move, taking something from one thinker and applying it to another, like using Aristotle in an unexpected context, influenced by the author’s professional background.

PK also mentioned the conservatism of certain departments, like East Asian Studies, and how game studies, despite growing, still faces resistance, especially toward video games rather than older forms of play. CW suggested that bias might come from the newness of the field. PK agreed and explained that he navigated this by combining canonical and non-canonical projects to gain acceptance. He spoke about the problems of archiving games, as hardware decays and old systems become unusable, giving rise to media archaeology, and argued that art museums should have dedicated spaces for video games. Reflecting on his own experience, he said he couldn’t have done this as his first project and had to build credibility through traditional scholarship. CW commented on the risks, and PK agreed, noting that departments claim to value interdisciplinarity, but conservatism remains, and one still has to belong to the “tribe.” The discussion ended with a reflection on the fact that the author uses Deleuze because he conducted a similar study of cinema, connecting the analysis to broader cultural questions. He further mentioned that analyzing 16–17th century texts through the prism of video games allows canonical works to be studied in a “non-canonical” way. All of this makes PK wonder whether he really needs video games to make the points he would make anyway!

Later, the discussion focused on why Galloway calls them “operators,” and CW said it’s like Barthes calling the photographer the operator. PK remarked that the author borrows from others but focuses on digital games and the non-human mechanics of play, showing how players become part of the machine. CW added that if you remove anthropomorphic language, playing becomes just a series of operations. This is a post-human move, i.e., when you play, you lose your human side and become like a machine, an operator. LDVG asked if the author ever gets to the social component and PK said no, Galloway is text-focused, looking at how consumers interact and how operators can hack or break the game. ME said the “game” metaphor is central because people play actively instead of passively reading. PK added that interactivity comes from TV culture, like a couch potato. He concluded that video games remain a medium we do not fully understand or have access to.

November 18:

Response #1 (NG)

In the first half of last week’s class we spoke about the final project, still in the making and very much in deliberation. Over the semester we drifted away from the initial idea of translating our own disciplinary-bordered works and assembling them into some kind of larger inter/antidisciplinary “commons” (if that was ever really the goal). Instead, the project now seems to be reaching for something more general, or even meta, about inter- or interdisciplinarity itself. Following the advice we received earlier in the semester about how to make interdisciplinary work function: namely, to put people in a room and give them a concrete task, we decided to stage a performance at the newly reopened Princeton University Art Museum in which we use a computer program to “translate” images into sound and play these sounds alongside the artworks.

The unifying theme is still unclear (“university”?). But what strikes me is that mediating between different modes of representation has led us to a double deference. First, we defer to the computer program that converts images to sound on what is, for us, an arbitrary basis. Its internal logic belongs to the code writer, and the principles of translation are opaque to us. Second, we defer to our three (amazingly generous) music experts, who will take our reactions to the images and make further adjustments to the sound so that it aligns with the feelings we want the piece to convey.

Seen one way, this could look like a betrayal of Rancière’s pedagogical principles of equality, since we seem to give up our agency to technical processes and to “disciplinary” experts. But a more charitable reading is possible. The project may be suggesting that collective, and even individual, antidisciplinary work depends first on trust: trust in peers who speak different professional languages, and trust in readers or viewers who will approach the work charitably. This also raises the role of the viewer or reader in antidisciplinarity. Presenting the performance in a public setting, where at least some of the audience will be non-academic is perhaps meaningful. The decision or commitment to appeal to non-academic viewers may be a prudential principle for antidisciplinarity more generally: it pushes us to translate, to negotiate, and to work against the gravitational pull of our own fields, even if realistically the final work remains within the sphere of the university or reaches only slightly wider audiences, much like the Princeton museum, which is housed within the university yet open to the public.

Response #2 (DA)

Act II

(Enter JC stage left)

Following a brief intermission, we are joined by our guest speaker JC. A round of applause! We are in the presence of a Tony Award winner!

SD and EB present a recap of what we’ve been up to thus far in HUM 583 in the form of script, delivered table-read style, managing to squeeze in all our visitors, Walter Benjamin, the almond milk, etc. It is, as CW later remarks, something like an extended inside joke, but it is more than that too, weaving together the months-long threads of our classroom conversations. JC, amused, uses the script as her jumping off point, in the “yes-and” spirit of the theatre, to talk about her creative practice, and to get us thinking creatively. We consider the challenges presented to us by the text, and possible ways we might begin to bring light to this surreal skit. We dwell on the possibilities of interpretation. What translates personally and how might that be translated into non-verbal cues? We think about how language does or does not translate into experience. JC advises always coming into design meetings with questions. It is not good practice to come with answers early on; not a good move to bring a thesis to the table. A reminder to remain in curiosity, no matter what discipline(s) we’re working within.

A lot of what we’re thinking has to do with collaboration, which is at the heart of JC’s work. In the Sound and Color Symposium recording, JC questions why we lionize coming up with “the big new idea,” suggesting that “probably what we need in the world is people who are really good at taking other people’s really great ideas and manifesting them in a kind of thoughtful, collaborative, inclusive way.” She calls for flipping the hierarchy of cultural values when it comes to creative output: “People who can work in groups of people and make something together in a way that sort of includes all perspectives kind of seems like the thing we most need as a globe if we ‘re going to move forward.” This was the section of the video where I paused to take notes and in class, KD picks up on this thread too. In class, JC speaks about the necessity of adaptability; of a certain kind of openness not only to sharing one’s ideas but also to accept that those ideas, the golden ideas you maybe stayed up all night thinking about, may not always be taken up within the context of a collaborative project. Bold ideas, loosely held, she offers — a phrase to hold as we approach the next stages of our final project.

November 25:

NAL+AR’s response

Owing to the fact that it was our last formal convening of the class ahead of the debut of our final project, much of the session’s first half was dedicated to firming up, democratically, the principles, constraints, equipment, and assemblages of the installation. Still, the conversation was no less lively and stuffed full of all the learnings collected by us this past semester. EC and “the sound team” directed our attention towards the modes of knowledge communicated through certain sonic modalities (bluetooths and surrounds vs. individual headphones), and an interchange between NI and ME helped sure up the performative bounds of our undertaking with NI posing the generative question: what does it mean to “bring” sound to the object rather than work with the truth of the object’s existing sonic state? There were a set of agreements reached, which I offer in summation below:

I. THE PROJECT WILL BE AN INSTALLATION— There will be speakers stationed at the selected pieces and attendees will be guided towards them, sonically animated from the start

II. THE PROJECT’S FINAL TASKS WILL BE DIVIDED INTO THREE GROUPS, A ZINE TEAM, A PERFORMANCE TEAM, AND A SOUND TEAM; THESE TEAMS DO NOT OVERLAP, NECESSARILY, WITH THE FOUR GROUPS CURATED PIECES — The Zine Team will put together text in a printed pamphlet that will guide installation attendees through the thinking of each group’s selected work and its inchoate sounds; the Performance Team will stage the flow and footwork of the exhibit’s run and also plan any fêting that follows this block; and the Sound Team will use the descriptions, formal and aesthetic interpretations, and affective suggestions of each curational group to produce each piece’s sounds.

The Performance/Logistics group consists of ME, ME, SC, MJ, SD, HF, NG, KD, and CW. The Sound Engineers are EC, LG, and

IH. The Zine group includes NL, NI, ST, LS, DA, AR, SG, EB, and NP.

Though there were only, seemingly, seconds left to chat about anything else, KN offered a 2x speed sound bite on Sara E. Johnson’s Encyclopedie noire: The Making of Moreau de Saint-Mery’s Intellectual World and the genre and tradition of Black Feminist writing and the publishing industry’s relationship to these epistemes. KN also plugged the editorial and curational care of Minneapolis’ Graywolf Press and its attention to glossy pages (And I, AR, who am currently reading Graywolf’s 2022 If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga, will only echo their catalogue and all its gems.)

In the session’s send half, we met our final guest, Rhaisa Williams, faculty in the Lewis Center for the Arts, who unlike other LCA affiliates who have joined us this term, is not a practitioner but an academic. This divide, between practice and academic writing, was the thematic clothesline upon which the many conversational interludes of our discussion were strung up. RW’s research, which takes up Black motherhood and its treatment in theatre, among other forms of dramatic literature, cohered in its own presentation the major, and minor issues probed by our class: the limits of disciplinary knowledge, the radical traditions, especially the Black traditions, which undergird interdisciplinary acts, the privileging of human subjects as human subjects above all else.

In keeping with the discussion in the earlier half of class, we explored various touchpoints of what constitutes “performance studies,” drawing largely from RW’s personal experience in Performance Studies (a slippery field of study). RW spoke of performance in relation to embodiment, noting how performance

can encompass questions about what it means to literally put things into your body, engaging with stories, people, and worlds one may not be able to anticipate. Performance studies in this way can offer embodied analysis of historical moments. The field, as RW evinced, is inherently disciplinary, but as with many of our class discussions over this semester, the contours of what interdiscipinarity means are constantly up for negotiation.

SG discussed their experiences in anthropology and the challenges in trying to make oneself legible in multiple valences across departments. RW used the metaphor of gardening, planting seeds in various places and cultivating those seeds for future-oriented work. ME asked RW about performance studies as a discipline, to which RW responded that they are less concerned in claims about what performance is and more interested in their actual subjects.

NI asked about how disciplinary distinctions with regards to performance plays out in the classroom, and CW mentioned the word “genealogy.” Our class discussion ended here: with RW’s reminder that often departments bear genealogical traces of the individuals who shaped them structurally.

December 2: