SEMINAR 1: We Begin!

[Class write-ups — DGB first]

Great to get started!

Our initial gathering, on a drop-dead-gorgeous early-autumn Wednesday, had no real reason to extend for the fullness of the two-hour-and-fifty-minute session. But it basically did. We just got going, and the conversation rolled along…

After introductions (great to have folks from so many different departments!), we turned first-and-foremost to the unusual wager of our class: a final collaborative project, the nature of which we know not – as yet. Because we are committed to the idea that it will emerge, in the course of our work together – and we are committed to honoring the process that gives rise to something we will do as a group (exactly how Christy and I will participate is TBD, but I have been willing to do my part in past years – and have generally contributed symmetrically with the students).

We talked a bit about some of the past projects that have come out of the course: the Keywords book, for instance (also a website); and there was the annotation exercise that was realized in a deck of cards (finalized in 2023, but it was the 2022 class that did the work). And other things too – some that took formal shape, and some not. We also discussed the way the projects have emerged, in the past, and spent some time on the “structure” that any such project has to honor (that there are components to be achieved individually, even as the whole wants to be greater than the sum of the proverbial parts). There are off-ramps, if we cannot get it all to work. But let’s shoot for the stars – and hope for the best.

🙂

We also spent some time on the structure of our sessions (with our initial hour together as a group, followed by the time with our weekly visitor), and reviewed the way we will use the “discussion thread” for a series of class “write-ups” aimed at documenting our work together over the semester.

The class’s special relationship with the IHUM program got some air-time, as did the nature of the IHUM program itself (though it was only after the break that we dug in on the “inside story” of IHUM’s origins – as a kind of consolation prize to the humanities after the creation of the Lewis Center pulled the arts out from under the “Humanities Council”).

That parenthetical above actually signals some of the substance that we got into AFTER that short break. Because it was post-break that we rolled up our sleeves and began to talk about what the class is actually “about.” And I hazarded that it has generally operated on two “tracks” in its pursuit of deeper understanding of the nature of the “disciplines” (and the various ways of scumbling, crossing, and defying them): on the one hand, we aim to follow a kind of “high road” of historical epistemology aimed at investigating the underlying conceptual rationale/geneaology of the modern university’s parsing of the domains of learning; on the other hand, however, we also try to stay mindful of the “low road” analysis of similar terrain, namely the “follow-the-money” project of understanding how universities actually work (which turns out to have considerable implications for what fields are available for study in what ways).

And what about our title words? “Interdisciplinariy?” “Antidisciplinarity?”

We have more work to do here. But we did circle the central fact that what organizes disciplinary endeavor in the modern university is the “production of knowledge.” That is what we are all here to do. That is what original research in a “discipline” amounts to – and each of you will need to achieve this in order to be “certified” with the Ph.D. That degree will designate you as a person who has created original knowledge in your field – as attested by a set of acknowledged scholars in that discipline.

Why take the time to scrutinize all of this in the critical/creative way that characterizes HUM 583 (if it works!)? Well, the answer to that lies, in good measure, in the way that the humanistic side of this “knowledge producing” enterprise seems to be in relatively serious straits – indeed, may even be coming to an end in its recognizable forms. And that means it is seemingly necessary to think hard about where we are (and how we got here) so that we can move to someplace else!

And in many ways THAT is the real program/ambition, I think, that churns at the heart of HUM 583. Let’s see what we can figure out!Very much looking forward to the semester together – and such a pleasure to have the chance to co-teach with Christy!

-DGB

[CNW here below…]

Am very eager to spend the semester with you all and to see what our unique combination of interests, talents, personalities, and knowledge sets will yield in the coming weeks. Was especially excited to meet students from so many different disciplines – Music, Classics, Architecture, English, French, Anthropology, History (of Science) – and to finally teach with Graham, which has been in the works for a while.

This is my first seminar co-teaching experience, so I’d never really thought about the extent to which one’s own professorial style takes on new meanings when put next to someone else’s professorial style. It is a rather intriguing feeling, and I see great potential in this new situation. There will be chances for speaking or being silent, playing devil’s advocate, making jokes, brainstorming, trying out wild experiments, arguing, agreeing, etc. etc.

Most of my pedagogical training has been in language teaching, and in past courses, I’ve borrowed language-centric techniques and applied them to literature, philosophy, culture, film, whatever I happened to be teaching. One certainly could bring in some of those principles into an experimental course like this one – particular ways of thinking about the time allotted to students vs. profs for speaking, the accumulation of more intricate tasks throughout the session, toggling between different skill sets (vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, etc.), which in our case might involve shifting from discussion of theory, to the anecdotal mode, to the possibilitarian mode (Möglichkeitsmensch or possibilitarian, a term from Robert Musil’s Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften [The Man without Qualities]), to a project-oriented or makerly headspace. Our guest speakers will surely bring their most natural pedagogical modes with them as well.

A tip, if I may offer one: As a grad student, you may not receive much pedagogical training, but I encourage you to watch each of our visitors and see if you can discern anything that one might describe as a pedagogy. Accumulate as early as you can a list of ways you’ve seen others impart knowledge and add them to your own storehouse for your potential future as a teacher.

Re: our first session, I very much enjoyed its rather strange order, which established itself seemingly organically. The collaborative project was the first order of business (wasn’t it? or it was at least alluded to) – DGB described it several times as EMERGENT, which I intuit may be one of his best-loved words – then lightning-fast introductions, some talk of class structure, then some chalk diagrams of everything from enrollment numbers to general education requirements to the arcane truths of program funding. Taking a page from the thespian arts, DGB did an impression of a wealthy donor who loves ethics, throws money at the university, then hobbles out the door. The IHUM program was explained. Only at the end of the session did the beginning happen: We addressed the question: What is HUM 583 about??????

Our session got me thinking about how much one’s perspective of the university changes from each vantage point. The ways that undergrads, profs, lecturers, grad students, staff, administrators, parents, donors, alums, etc. experience the place, make judgments about it, and move through it are quite incomparable. I hope that in the coming weeks, we will keep in mind that it is quite difficult to say anything definitive about this particular institution because it changes so tremendously depending on the subjectivity through which it is filtered.

Regarding the General Education Requirements that undergrads have to meet in order to graduate, DGB brought up the specific impact of the HA requirement (Historical Analysis) on the numbers in Kevin Kruse’s 20th-Century American History course and other classes in the history department. Here are the other requirement categories, which, you’ll see, certainly have a disciplinary (and sometimes thematic) understanding of undergrad education:

- Culture and Difference (CD)

- Epistemology and Cognition (EC)

- Ethical Thought and Moral Values (EM)

- Historical Analysis (HA)

- Literature and the Arts (LA)

- Quantitative and Computational Reasoning (QCR)

- Science and Engineering (SEL/SEN)

- Social Analysis (SA)

I would be quite interested to hear what you make of such requirements. Also, does your particular program require specific courses or specific families of courses? What is the rationale for this course distribution?

In other university cultures – I have Europe in mind in particular – students begin to specialize early, making important choices about their disciplinary direction much earlier than Americans, sometimes even in high school. Perhaps we could talk about the advantages and disadvantages of such early specialization, about the idea of a “well-rounded education” or the goals of the liberal arts college (versus places like community colleges, trade schools, big public universities, research universities, etc.)

A final surreal note: I printed out the pages for the Week 2 readings and when I got to the Foucault pages, I found a surprise. On the screen the page looked normal:

But on the printed page, the letter “O” had gone on sabbatical:

Surely an OCR issue? A printer issue? In this format, Foucault’s text seems less like a scholarly contribution and more like a code to be cracked.

Excited for our first guest, the unparalleled Jeff Dolven, who will likely give us other enigmas to solve.

-CNW

SEMINAR 2: With Jeff Dolven

The first third of class, we were among ourselves. CB placed the Reunions button with its divestment QR code on the table, summoning up the past (last year’s protests), the present (Beshara Doumani’s recent talk in NES), and the future (talk of a future Palestinian Studies unit on campus). I was quite sad that we weren’t able to get LJ’s object on the table by the end of class but really hope we’ll be able to see it first thing next week. Raymond Queneau’s Cent mille milliards de poèmes (A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems) got passed around the room, its versed strips bending into new configurations in each student’s hands.

Jumping into the knowledge reader, wide-ranging observations came in quick succession. We talked about the styles and themes of the readings by Wittgenstein, Vico, Ryle, Foucault, Haraway, Harvey, Moten, and Hegel. Many of the articles were about typologies and finding ways to name and categorize various types of knowledge. SW pointed out the humanities-centric nature of the reader. The poles of constraint (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle) and freedom (Surrealism) were played with. SS offered interesting observations about the music program, which separates the musicology, composition, and performance tracks in substantial ways, causing potential tensions between them. This made us dwell on the problem of interpretation: How to describe the similarities and differences between the task of literary interpretation (the act of the critic) and musical interpretation (in the performance sense)? Which is valued more in contemporary academia? The interestingness of our discussion caused time to accelerate markedly.

During JD’s visit, we moved into a specific discipline – literature – but what quickly came through in the discussion is that poetry (not poems) transcends the category of literature. We spent a lot of time on the commonplace and tried to figure out how specific commonplaces from Grossman’s text did their work and what a commonplace is and can do more generally. I threw in the problem with commonplaces – I described them as pithy dispatches of truth – and their tendency to provide what I guess you could call situational truths. Commonplaces offer one meme for this situation (“Absence makes the heart grow fonder”), an opposite meme for another (“Out of sight, out of mind”). The example I offered is the variants of “Clothes don’t make the man” (near synonyms in English being “Don’t judge a book by its cover” and “All that glitters is not gold” and funny equivalents in other languages, including the very Catholic commonplaces from French (“L’habit de fait pas le moine” [the habit doesn’t make the monk]), Italian (“L’abito non fa il monaco”) and Spanish (“El hábito no hace al monje”). German provides an opposite commonplace: “Kleider machen Leute” [Clothes DO make the man.] Grossman’s primer offered a catalogue of poetry-related commonplaces that sometimes contradicted each other, sometimes mutually reinforced each other, and sometimes stood as outliers, having less the feel of a commonplace (accessible to, legible by, and maybe even producible by all) and a one-off poetic reflection written in aphoristic style. A favorite line from the intro that we didn’t discuss: “An aphorism is a proposition with a horizon.”

The word speculative caught and held my attention most tightly. About 10-15 years ago, there was a trend especially strong in European and American philosophy of pinning “speculative” to a lot of other terms: speculative realism, speculative materialism, speculative justice, the speculative turn, etc. (The philosophers Quentin Meillassoux and Graham Harman are probably the most well-known people attached to it). The language of a “radical shift in philosophy” was omnipresent then, but if you are not a philosopher, you probably took no notice. (I wrote a critique of speculative journalism some years ago, in a completely different vein from the above-mentioned philosophical exercises.)

What does Grossman mean by “speculative poetics”? We speculated about what he might mean but didn’t settle on an answer. Or rather, we offered multiple potential answers. I was disappointed that we didn’t get to JD’s wonderful * A New English Grammar, which is a poetic experiment of the richest kind. My favorite sentence: “A complication arises with verbs like die” (22).

Wanted to flag the discrepancy between the first half of class and the second half, which piqued my curiosity. In the second half, some people spoke much more than others. Was it because some were familiar with the lexicon of poetics and others weren’t? Was it too abstract for some, comfortably so for others? Did it have to do with shyness in the presence of a guest? Will there always be a vibe change between part one and part two? Almost certainly. Just wondering about its causes. This has broader implications – I think – for many of our future discussions on pedagogy, the classroom, types of learning environments, classroom dynamics, etc.

-CNW

[DGB here below…]

Walking back across campus after our seminar today (the late afternoon light already autumnal, the quad quite embarrassingly beautiful – most lively and contemplative, in a very start-of-the-semester way), I found myself feeling genuine waves of very deep gratitude. What an immense privilege (and pleasure!) to be able to spend two hours and fifty minutes doing that! And with all of you!

I suppose it is really a little cheesy, all that: a middle-aged professor getting tingly about the joy of seminar. Good heavens.

But it’s true. I can’t deny it. I experienced, across that last eighty minutes or so a genuinely exquisite, even exhilarating, sense – the sense that we were actually doing a thing that I love very much; that we had, together, with Jeff’s deft leadership, successfully made a set of genuinely profound questions vibrate.

Is that the right way to put it?

It is obviously a metaphor. It captures something, though. Because we didn’t exactly “answer a question” – or not in any obvious way, I don’t think. Nor did we “produce knowledge,” did we? Certainly not in any way that would be recognized through the social technology of peer review.

What did we do, then?

We read. We thought. We talked.

And in the course of those activities, I began to feel a certain vibration in the room. Was this an illusion?

If it was a “vibration,” what was vibrating?

I am reminded of Jeff’s touching valediction – that part where he drew the distinction between an interdisciplinarity of hyper-specializations (imagine two disciplinary “trees” whose most extended ramifications can rub together… and produce an article) as against the “interdisciplinarity of the fundaments” (the going down into chthonic foundations).

Do you remember this? Did it make sense? I think we will come back to this idea, but for now I want to invoke Jeff’s parting words. As I heard him, he left us on a note that harmonized encouragement and warning: that second kind of interdisciplinarity, the one that involves going toward the fundamental (basic?) stuff, is, he seemed to be suggesting, where the best of the good stuff lies; however, going there demands that we be a little fearless, because there is no place to hide, really – no sophistication or referentiality that will protect us from the taint of shame/embarrassment. “Take heart,” Jeff seemed to be telling us, “you have to risk seeming a little silly if you hope to enjoy the riches and satisfactions that are to be had down there where the most basic questions get asked.”

I suppose I am thinking of that moment because, reading back over what I have written above, about “vibrations” and all that, I am struck by how goofy it can easily sound, how pre-stressed for sardonics (“oh really? you guys had a seminar? and you felt, Graham, that you were all…really vibing?”).

But I guess I mean it. And I want to stick with it, despite feeling bit of that shame that Dolven invoked. Vibration. It’s the best word I can come up with. It felt to me like we made some very large and very old and very deep questions vibrate. That we did that together.

Vibrations, of course, are the stuff of sound – indeed, of music. And so it might be more poetic (though not for that false) to say that we made those deep, old problems sing.

Yeah. Well. Hmmm.

What does Grossman say at one point? “While I am doing this, you are doing something else.”

So true. So true. And it applies RIGHT NOW! I am trying to explain what it felt like to me. You are reading what I wrote. (Something of this problem will be in the first-hour reading set for next week, on the problem of “experience”…)

And, as far as “what it was like for me,” I’m not sure my writing is especially helpful, as I look back on it. Oh well. As Grossman asked us to acknowledge, this is rather the central problem we circle, we who care so much about humanistic objects (“texts,” “works”) and their situations.

As for “vibration,” there is, as it happens, some nice peer-reviewed literature out there. I know a little bit. Has it informed my metaphor? I can’t say. Does it actually help? I’m not sure. But here it is, for what it’s worth: Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World.

Oh, and vis-à-vis the whole business about the embarrassment of fundamentality”: I use the word “fundament” above advisedly – it does, of course, in English, mean, somewhat dismayingly (or should I say delightfully?), both “the foundation” and “the buttocks” (the artist Matthew Barney, in his endlessly queasy way, helpfully taught us to keep both meanings in view…).

Onward!

-DGB

In thinking back our conversations over the assigned texts on truth/knowledge and in the time shared with our guest, JD of English, three themes stick out to me as particularly prominent (and fascinating!). None of these ideas reached resolution or closure – perhaps/hopefully none have one. And each overlaps and intertwines substantially. I’m looking forward to continuing to pull at these and others over the semester.

[I’ll also acknowledge, in partial response to CW’s posted note, that my descriptions lean slightly more heavily on the first half of class than the second, and that I likely missed some key points on account of being disciplinarily/theoretically out-of-depth!]

(1) What is knowledge, and what are our obligations as knowledge-producers?

[CB] got us started with a powerful object, drawing us in to recent discussions on campus, and around the nation, about the importance of Palestinian (different from Palestine) Studies as a discipline, and potentially department. We thought about the legitimization of disciplines, the powers (high-road and low-road, re: Session 1) shaping the development of this sort of department, and the need for the thinking and knowledge-production/doing that a department like this would foster.

A good bit of our first-hour conversation dealt with questions of knowledge-production, and the ways the University/Academia differentially values knowledge and modes of production. The language used for roles within that spectrum arose in multiple ways, including [CM]’s example, and [CW]’s additions, on the differences between French’s chercheur and English’s academic, intellectual, researcher, etc. The Ryle excerpt called us to consider tensions between thinking and doing, those who design the product and those who carry it out, the clock-maker and the clock. [SS] named the ways in which this is explicitly played out in the musical world, with musicologists and not compositionists holding tenure, and those who perform compositions unrecognized for their contributions in the economics of university degrees.

Continuing in this tension, JD opened by naming that interdisciplinary work often most-comfortably takes theoretical forms, and that he intentionally confronted that tendency by assigning readings on doing, on craft. The foundations of the Grossman piece, as a set of commonplaces that aren’t theory, but instead points of outlook, forced us to sit in the practical, even within knowledge-production. We discussed the moves that Grossman made in the structure of the Summa Lyrica, decontextualizing things that are familiar, and in doing so emphasizing their striking nature, producing the commonplace as something we know but must also learn. (I might add here a connection to Hegel’s discussion on the knowability of the familiar in the reading).

(2) Communication, distancing, and representation: is there ever proximity?

Much of our discussion with JD centered on ideas of communication and proximity. [AK] began this with commonplace 16.7, on ideas of hearing vs. overhearing. We discussed multiple forms of art that pull at this tension in different ways, including the power in art of representing subjects in states of absorption with objects invisible to the viewer, and the oppositions between absorption and theatricality. [MM] drew us to Said’s work on eavesdropping, and [CM] to Baudelaire’s contrary direct address of the reader. We held in tension these directions of intention with ideas of the production of poetry itself as necessarily in-community (Moten).

Hand-in-hand, [MA] pointed us to commonplace 2.3, grounding us in the practicalities of conversations to determine-the-relationship. We discussed Grossman’s fascination with identifying/exposing the hidden, and with the aesthetics of distance and participation (later in the conversation, re: commonplace 32s) as intertwined and contingent. [DGB] and others contextualized Grossman’s work to the moment wherein communication theory was burgeoning. This allowed us to wrestle briefly with the mismatches always between what is said, what is heard, and what is inner/unrepresented, and particularly with Grossman’s proposition that you can never fully Say No (2.3, p.215).

JD closed us on commonplace 30s, drawing urgency to our tasks as knowledge-producers with the claim of the “banishing” that is done in interpretation. We touched on the perhaps-inevitable impossibilities of interpretation, our tendencies to get at what we want a text to mean (or, Haraway, perhaps our incapability of doing anything else) and our pursuits to get at what we think the author means.

(3) Is there a way to theorize and make-knowledge free of this “factory” (Moten & Harney), this “disciplining” [MM] and “constraint” [CW]?

[SW] noted the theory- and humanities-heavy nature of our readings in the first half, wondering how truth and knowledge are defined in more empirical realms. This led to a brief discussion of the ways in which the humanities’ traditions have been formed from, and are constantly in the position of proving themselves to, the traditions and empirical values of sciences.

Interlinked, [MM] brought up the disciplining power of the academy – seeing us, students/academics, as the clock/seal/worker, and not the thinker/producer – and posed the question of freedom. This led to multiple board-discussions, including [CW]’s on the range from freedom to constraint, creative work produced at both extremes (e.g., Cent mille milliards de poèmes, Queneau). [MM] challenged this line, pushing instead for a new model:

Freedom ——————————— Freedom

with one being AAS’s ‘emancipation,’ or freedom only to be workers within capitalism, which isn’t really freedom at all, and the other being some True freedom, which might be undefinable by definition. [CB] added the example of Mark Walliger’s il/legal+unpunished recreation of Brian Haw’s il/legal+punished protest art (https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/mark-wallinger-state-britain).

Our time with JD ended with a discussion of one seeming-response, if not to this question, then perhaps to one parallel. In looking at the Summa Lyrica’s Commonplace #30s, on the “crisis of interpretation,” “the community can be healed when the members turn away from the text and toward one another” (p.285). We discussed the challenge these claims bring to our work, as interpreters, the importance of form and structure because of the ways they bring us together, and the potential for hope in “looking up and allowing the text to be present.”

Does this sort of abandonment/letting-be get at a freedom, as [MM] articulated? Is this so radically different from the “disciplining” and “constraining” of our factory as to provide hope?

-GS

Wow, thank you to GS for that synthesis! My discussion post will be a bit more about my personal takeaways and questions related to the first half of our session; specifically, the first question GS posited: “What are our obligations as knowledge-producers?”

I imagine many of you have also spent time this year puzzling over what education is “for.” As CW and GS mentioned above, we began class focused on CB’s button from the 2024 Reunions Divestment protest, which reminded me of the flurry of student activism on college campuses nationwide this past academic year.

(As an aside: encampments themselves were denigrated by the media and university officials, even criminalized. However, some schools have “acceptable” traditions of encampments: for example, Duke has a long tradition of months-long encampments for basketball tickets. Basketball tickets! Hundreds of people camp outside in a school-sanctioned endurance marathon that, in my eyes, makes the argument that ‘encampments are disruptive’ moot.)

CB’s discussion of Beshara Doumani’s talk on the academization of the field(s) of Palestine/Palestinian Studies led to a conversation about the recursive relationship between activists and the (uppercase A?) Academy. As an undergraduate, I majored in the Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality (WGS), which was, unlike a department, an interdisciplinary program that did not have a single devoted faculty member until my last year of college. It baffled me as a student that despite high enrollment numbers, most WGS classes were taught by visiting assistant professors and adjunct lecturers.

I was thus intrigued when SS mentioned that the Music department’s two tracks, composition (creative) and musicology (analytic), are treated differently. The fact that composition faculty are not tensioned thus led us to ponder: What type of knowledge is valued—or holds “economic value”—for the university? The University’s decision to create different “tracks” even within departments signals how it values “knowledge producers” differently and sees each of us as investments of different economic value.

We concluded the discussion of Christian’s object with three questions: what is education for? Is it to make “good citizens,” and if so, is good citizenship what students should aspire to?

The question reminded me, once again, of universities’ (or the university-industrial complex’s) inability to reconcile students’ dual identities as consumers and citizens.

This past May, I volunteered at my alma mater’s commencement, where all three of the school-sanctioned student speeches deplored the decision not to allow several of the students involved in demonstrations for Palestine to graduate. The faculty voted to allow students to graduate, yet the university’s corporate board overturned the faculty vote. This decision signaled that the ultimate decision-makers for the university were not its producers of knowledge but its shareholders (producers of capital). This begged me to ask: what is (or should be) the “product” of the university as a corporation? Is it tuition, the degrees, or its revenue-generating investments for the endowment? Who ultimately benefits from this perversion of value? Finally, if tuition-paying students are the “consumers” or “customers” of the university, are those who attended with full or partial financial aid considered secondary or even noncitizens?

This last question relates to the issue of the position of class in academia, both within the student body and as a professional category. The question about what education is for leads me to wonder who different versions of education are for and how we signal our investment in them accordingly.

Last week, I talked with two friends about whether humanistic studies (from Latin to Shakespeare to cursive script) will be taught to future generations. One of them, a poet turned venture capitalist, wagered that the question required us to ask what K-12 education should be for: should federal education policy intend to create workers or managers?

As a product of public schools, I was quite jealous of my peers who came to college laden with the knowledge needed to follow (and dominate) humanities classes and spaces. In addition to other class differences, one that I saw was their comfort in thinking out loud and their much wider understanding of canonical references.

Though I took many “AP” classes, these classes were geared toward acing multiple-choice questions and writing essays formulaically. Searching “AP Lang” on YouTube provides us with an insight into the “essay formula,” as videos with hundreds of thousands of views help students “Get a PERFECT SCORE on the SAQ (APUSH, AP Euro, AP World)” and teach them “The ONLY AP LIT THESIS Template You’ll EVER Need!”. It is an unfortunate reality that many of the undergrads who come to Princeton received similar instruction from their teachers at schools where getting 5’s on AP exams influenced both school funding and students’ college applications. At the same time, many of our students will come from private institutions where teachers hold doctorate degrees, grades are not given, and coursework is designed to improve students’ reasoning, not memorization, skills.

I wager that critical reading and thinking should be skills that a democracy should value. If so, students of all ages should be encouraged to learn the many ways of knowing, not just memorization. Thus, should we not aspire to create a truly “educated” citizenry, where each of our citizens has been given years of training in critical thinking?

As (re)searchers (As Claire introduced, ‘chercher’), we have what Foucault calls “noted, political responsibilities” peculiar to our specific class position as “intellectuals” (a category I aspire to but also find… a bit distasteful? Classist? Performative? Dare I say, cringe? Or as Gen Alpha says, ‘Ohio’). Harvey and Moten pointed out that my anxieties about the cringiness of the “intellectual” profession stem from my complicity in it as someone who made conscious decisions to seek and accept opportunities in the Ivory Tower. Woof!

Many of our seminar members and JD had insights about the Summa Lyrica that I never would have thought of. My mind was truly blown that the Summa was a reference to Aquinas’s Summa Theologica (again, an instance of the type of reference that may be lost on future generations if robust humanistic studies do not continue). Had I known this before, many of my questions about Grossman’s form and writing style would have been answered! At the most basic level, I did not realize that ‘commonplace’ was the term used to reference each numbered paragraph of the text.

Thus, as I left our time with JD, one of my questions was: how do other people read??? That is, how do others approach a text for the first time? What do you do while reading—do you scribble in margins, underline, or look up words you don’t understand? Do you bulldoze through and then re-read (as I generally do)? And what do you do when you read and re-read but still don’t know what is happening?

-SY

SEMINAR 3: With Brooke Holmes

[DGB writeup starts here]

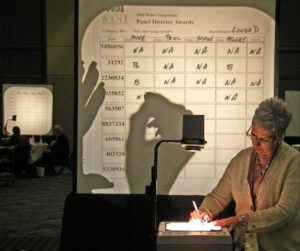

I am writing this within 45 minutes of the end of our seminar. And that means I still feel, quite strongly, a kind of tracer or afterglow of our time together. We covered quite a lot of ground (as the photographs of the blackboard indicate), but the dominant intellectual “mood” that holds me in the wake of our seminar is something like “dissatisfaction.” Not my own (I am afraid I again found the session almost too pleasurable to bear!), but rather the compelling, fully inhabited, and well-nigh heroic dissatisfaction that our extraordinary guest, Brooke Holmes, seemed, somehow, to radiate, relentlessly, in relation to the work of… well, doing whatever it is we do.

I can hardly think of a more charismatic manifestation of a critical sensibility. I really found myself mesmerized by the fluency with which Professor Holmes brought us in not only to the fundamental/profound thematics of her current book project (on nature itself — or, the emergence of a concept of nature that can “orchestrate relations”), but also to the actual quality or character of her thought itself. This, too, she shared with us, I felt, and did so with an uncanny generosity.

This is a hard thing to talk about well. It intersects with ideas, but is not coextensive with, or entirely composed from concepts. It is not a matter of mere affect, though affect is relevant. To suggest that the issue is one of “psychology” or (heavens!) “personality” would be quite unsatisfactory — and yet perhaps not entirely wrong. Brooke Holmes showed us the way she again and again thinks the thought, and then thinks the conditions of possibility of the thought (which thereby condition the thought), and then thinks the limits of the thought in its contingency, and thereby the alternatives and the adjacencies of the thought which confound and/or exceed it, and then thinks the conditions of possibility of THOSE thoughts, and so on. The word I keep reaching for is the one I have already used: relentless. Coupled with another, which I have also already used: critical. I felt I was experiencing a very pure and very precious manifestation of relentless criticality at its very best— its most brilliant, its most faithful, its most richly equipped.

There was a moment in all of this (I wish I had it recorded, so I could get it exactly right…) in which, as I recall, Professor Holmes seemed to throw up her hands, only partially in jest, and to call out what could suddenly seem, in the glorious churn, like an impossible problem: how to get it all down! Putting it into some kind of “narrative” (this was the term that got used several times across our conversation) could exactly feel (I felt it myself!) like nothing other than a static betrayal of the exquisite and continuously clarifying/destabilizing other-thinking moves by which the actual thinking itself did its work.

I am not, myself, that kind of thinker. But my admiration for that enterprise/sensibility is enormous. To have the opportunity to sit so close to such a powerful display of this project genuinely felt like a privilege.

So I guess I was “vibing.”

🙂

There’s that term again. We shall probably need to dispense with it relatively soon. Although it was especially relevant this week given the centrality of “sympathy” to Professor Holmes’s analysis of nature and the body and “relationality.”

Although it is all so hard to understand. After all, I definitely felt that I was “sympathetically connected” to Professor Holmes’s account (of the challenge of holding genealogy together with historicism, of the challenge of coordinating ethics and physics within the framework of secular modernity, of the challenge of dislodging the givenness of this or that naturalism while refusing to naturalize such dislodging, of the challenge of holding space for aesthetics without embracing the mystification of a “mythos”), but I actually don’t really “agree” at all, on some level. Which is to say, I feel as if I was understanding what she was saying in an enormously gratifying and clarificatory way, even as my own positions are, in the end, I believe, quite different from her own.

I think that puzzle (if it is a puzzle) — that understanding “not” (or whatever we want to call it) — came up directly in the course of our conversation. Or, at least, I think it did. I am referring to our effort to reckon with the Joan Scott, as occasioned by MM’s probing the “non-vibing” of difference.

Do I have this right?

This stuff gets too hard to do well this way (in a short and effectively personal/informal reflection). And it may be too hard to do any way at all. But one senses a kind of trembling parallel between the understanding-of-that-which-is-outside-of-one’s-understanding and the classic philosophical problem of attention-to-something-that-is-not-present (see Jonardon Ganeri’s fascinating essay, “Attention to Absence and Imagination” in this book I helped put together recently).

I won’t try to do much with this hard problem. Although perhaps I can conclude with a brief reflection on “history” and “genealogy,” which can be understood to play their own parts in this drama.

Historicism, in its commitment to pinning everything to its place on the timeline of chronos, can be understood to be a perpetual mechanism of distantiation: everything is in its moment and it is held there by time itself; things don’t move around, and every time is its own.

Genealogy, by contrast, is all about tendrils of connectivity. It is exactly the project of threading lines of continuity between then and now. By these lights, historicism lines up with the endlessly differentiating and specifying activities associated with particularizing and difference-making/seeing. Genealogy, by contrast, lines up with those “rightfully suspect” (?) programs of transhistoricity and universalization.

But such a simple-minded chalktalk hardly does justice to the complexity of the whole thing. After all, as soon as we have filled in all that monadic specificity on the timeline, we have in fact achieved a continuum, a plenum or manifold linking everything to everything else. Something like this is what I was getting at as I sort of feebly enquired as to the ways that difference continuously reconfigures itself in patterns of coherence and coordination. But I am susceptible to the allure of such jumping together….

Anyway, this stuff gets complex beyond my kenning. But I felt we had those problems alive in the room on Wednesday. Not sure more can be hoped for?

Oh, and then there was this ^^^^. To think on…

-DGB

[CW starts here]

LJ brought us wooden blocks of her own amazing design – I especially liked the permission she offered not to be shy about their loud clacking against the table – which brought the concept of play into our discussion. (Barthes’ famous essay on toys from Mythologies came to mind… He argues that the role in France of toys is to indoctrinate children, preparing them for their future social roles.) There was a quick collective brainstorm re: toys (their social meanings, materials, experiential/educational possibilities; LJ and SY – I think? – also mentioned the term “modularity” and various ways that play, gaming, experimentation, etc. might be used for the final project.)

Experience was the word of the day: What does it mean to have an experience? How does one accumulate experience(s)? Where does experience come from? How does age relate to experience (we didn’t really talk about this aspect, but some of the readings gestured toward it)? Who has permission to narrate one’s own experience or the experience of others? Under which conditions? How can one experience art, writing, music, cinema, a traumatic event, a particular state of mind? In what form(s) can it be transmitted to others?

Like AK, I found the Dewey reading especially fruitful. Without using the word Erlebnis, he dwells quite a bit on that type of experience – the kind that lets you say after the fact that you’ve had AN EXPERIENCE. He writes, “[…] we have an experience when the material experienced runs its course to fulfillment. Then and then only is it integrated within and demarcated in the general stream of experience from other experiences. […] Such an experience is a whole and carries with it its own individualizing quality and self-sufficiency” (35). Such experiences exist as discrete units in time, something finished that might still exert influence on the person who had it. The other kind of experience – Erfahrung – is cumulative and involves an increase in one’s abilities: “I have experience with/in …” It can have professional connotations – CVs are filled with lists of this kind of experience.

I was particularly struck by SW’s remark about modernism and the way it tested out so many different modes of representation in order to capture new kinds of experience (or its loss, as Benjamin alluded to) caused by a situation of total war, technological acceleration, social upheaval. The Woolf passage from Mrs. Dalloway I mentioned happens after a car backfires on the street and the shell-shocked Septimus descends into his own combat-worn consciousness:

Septimus looked. Boys on bicycles sprang off. Traffic accumulated. And there the motor car stood, with drawn blinds, and upon them a curious pattern like a tree, Septimus thought, and this gradual drawing together of everything to one centre before his eyes, as if some horror had come almost to the surface and was about to burst into flames, terrified him. The world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames. It is I who am blocking the way, he thought. Was he not being looked at and pointed at; was he not weighted there, rooted to the pavement, for a purpose? But for what purpose? (15)

We got to talking about the fact that knowledge isn’t necessarily what Princeton markets to undergrads but rather EXPERIENCE. Out of curiosity, I tried out the keyword search “Princeton Experience” in my browser. Lots of stuff like this came up. Everyone in the group seemed to acknowledge pretty quickly that grad students are “marketed to” in a very different way. More emphasis is placed on academics and less on extracurriculars. Perhaps because undergrads are paying to go to Princeton and PhDs are being paid? Hope we will pursue this further in our discussions.

BH’s presence brought me lots of joy, if for no other reason than the chance to witness the vastness of her knowledge and the thoughtfulness with which she approaches every problem, all with great humility. I appreciated her exasperation with a genealogical model that traces everything back to the Greeks. We are all doing our work at an American university whose administrative structure, architecture, course structure and content, etc. are mostly modeled after European universities, which turn constantly toward Greece (and Rome, to a lesser extent) as the root, cradle, foundation [pick a metaphor] of the modern university. [Loved the Foucault interview subheading: “Why the ancient world was not a golden age, but what we can learn from it anyway”] (256). What to do with these default settings? I suspect that in coming weeks, we’ll begin discussing the “unnaturalness” (to use a term from one of the readings [not sure which… maybe more than one?]) of these settings, to brainstorm about new settings, ones more suited to the current political, social, and technological realities in which we find ourselves.

Too many thoughts on the Foucault interview and BH’s wonderful book chapter to sum up here, but these pieces added a lot of new terms to our course lexicon: biopower, history, storytelling, the “modern subject,” nature (phusis) and law (nomos), etc.

[SD & CMP starts here]

While reflecting on this past Wednesday and our meetings together so far, I was struck how we keep imagining or creating couplets. One part of the couplet is more scientific. The other is more amorphous, or “vibes-y.”

Last week (9/11) we put ACADEMIC vs. INTELLECTUAL up on the board. Though one can be an intellectual and an academic, the two are not synonyms. We posited that “academic” implies something productive, professional. “Intellectual” is more nebulous. One could be an intellectual and spend their life thinking without channeling said thought productively. “Intellectuals” are often ridiculed as the folly and recalcitrant individuals who refuse to conform with the norms of a corporate society.

This week brought several new couplets.

[LJ]’s wooden Blocks set the stage for a conversation about the relationship between the material world and text/thought—and play as a way of connecting to the places we call home. [DGB] latched onto PLAY as concept we might take up as a counterpoint to the university and its insistence on disciplinarity/professionalization (self-seriousness?).

With play as a seemingly lighter, but no less rich alternative in mind, many further couplets emerged through our discussion.

First, a thought. Are we entering the Mind-Body debate once again?

“Where has it all gone? Who still meets people who really know how to tell a story? Where do you still hear words from the dying that last, and that pass from one generation to the next like a precious ring? […] Wasn’t it noticed at the time how many people returned from the front of silence? Not richer but poorer in communicable experience?”

(W. Benjamin, “Experience and Poverty”, p. 731)

As we read selections from Walter Benjamin’s “Experience and Poverty,” [CW] proposed that the German words “Erfahrung” and “Erlebnis” reflect two discrete meanings of EXPERIENCE. As previously with ACADEMIC and INTELLECTUAL, eRFAHRUNG and eRLEBNIS fall into two distinct, broad categories. “Erfahrung” connotes something more fixed, vocational, concrete linear: a set of experiences (work, competences, etc.) that one would list on their CV; practical knowledge accumulated over one’s lifetime. “Erlebnis,” meanwhile, suggests something that happens to you, that you might tell a story about, the forms part of your life, something extra-linguistic and not immediately transferable as a SKILL.

We also immediately questioned the notion of a “communicable experience”. What does it mean to talk about an experience that exceeds the two dimensional space of the words? That exceeds even feelings and understanding? [Is this a third category?]

Round-table discussion: what about your field? This part of our class resists categorization. And yet it too aligns with our couplet schema.

There is an ongoing debate in the field of history. [HH] asks, in intellectual history, is an “idea” an experience? [SD] wonders, is something “real” in history if it is not recorded, legible, part of the archive?

The position of the scholar. In the field, more and more people question the position of the scholar related to the history they are trying to tell. In other words, where can we find legitimacy in the narrative? Should scholars try to focus on their stories only? Or: should they be part of the story to access it?

And what does it mean to be part of a story? To EXPERIENCE it?

Once again, the “communicable experience” emerges in a two-dimensional space: the bodily experience of the element and/or the moment (EXPERIENCE), and the linguistic experience of the scholar telling (KNOWLEDGE).

- Literature and Realism: do the writers really want to show reality? Or to recreate it? As a scholar, what is your position: should you try to reach the experience of the reader? of the writer? of the character..?

- Exhibitions exhibiting: most of the museum nerds would have experienced it, museums are now becoming immersive. But what about the other experiences? Who should experience what in a museum?

[SY] discusses the Family of Man exhibition at the MoMA. Can people have different experiences that lead them to the same idea? [AK] brings in empathy theory.

[CMP] asks, [SS] discusses—Have you heard this musician playing? They clearly have no experience of this piece.. No emotion, no feelings.. Sounds mechanical.

BH arrives. We take a break. We’ll get back to couplets in just a second.

Story-telling with BH – why, what, when

Maybe you could start by presenting yourself?

[BH]Well, I chose Foucault and then my text and then I thought: ‘What am I doing?”. But I thought that you would help me with that.

Foucault chose to present a history of concerts, and Brooke started with two of them: nature, and sympathy, from the Greek SYMPATHEIA (transfer of affects between bodies).

- Isn’t it logical, given these concerns, that you should be writing a genealogy of bio-power?

M.F. I have no time for that now, but it could be done. In fact, I have to do it.

(On The Genealogy of Ethics – AN OVERVIEW OF WORK IN PROGRESS)

Foucault actually never had the time to properly work on these questions because he already knew that he was dying at that time. Instead, he just hint at this concept, the “bio-power”, thought as a mix between physics and ethics.

Couplets come back! And do they relate to disciplines? Are some humanities disciplines more scientific? Others more vibes-y? Or are there maybe more than two things?

Here, too, came the idea that disciplines could be sorted into one of our two categories. [BH] briefly mentioned the idea that Classics is a very “bounded” field—with each professional classicist expected to be fluent a set and contained canon [a note—there is an irony here in BH “disciplining herself” from the wider field of Comparative Literature while invoking Classics to explore modern bioethics]. History contains a set of methodological expectations, yet unlike the set classical cannon, one can feel overwhelmed by the “infinity of the archive.” [BH] insisted on the fact that, inspired by Foucault, she wanted to do an “oblique methodology” and a theory of reception, between ancient (Greek) and modern.

[BH] said “Oftentime, I think: ‘Oh no.. not the Greeks again!!’”

[DGB] said “Should we get back to the opposition between historicism and genealogy?”

Three terms emerged (three concepts? A triplet?) for [BH]: the question of GENEALOGY (Foucault’s method), the question of the MYTH (classicism and naturalism at the same time), and the question of the AESTHETICS (experience and existence of the everyday).

[BH] questioned the relation between history and storytelling in this context: How could we study the Greeks without the storytelling and the myths? [BH] mentioned a talk where the Odyssea was studied through the motif of the “sea”, instead of providing the usual long contextualisation.

Couplets strike back, again. Seemingly organically.

[BH] introduced us to the notion of CHRONOS vs KAIROS, or chronological vs. kairological time. “Chronos” falls on the same side of the divide as “erfahrung” and “academic.” Chronological time is necessarily linear, metronomic, plodding, mechanized, operating, scientifically, in the background of our experiences. Kairos, meanwhile, embraces a warmer and more qualitative vision of time, as a composite of moments we reflect on as being full and consequential. “Kairos” seems more accepting of the idea of time as a circular, ruptural, or fractured thing.

Reflecting this division were a few additional couplets [BH] mentioned: ONTOLOGY vs COSMOLOGY, where ontology carried with it a more “fixed” understanding of “being,” and “cosmology” something with more porous, blurry boundaries; genealogy vs. historicism, where genealogy invoked myth to trace the particular, monolinear origins of a present-moment thing, and “historicism” sought to embody the present as it was, employing narrative, individuals, “Kairos.” [BH] also pointed out the difficult reconciliation between the “Chronos” and the “Kairos”, since the Chronos is most of the time used as an instrument of domination. She offered to use the idea of “liquid Antiquity”, in opposition to the “iconic Classicism”.

I’ve been thinking about whether the class itself divides, in a way, into these two broad categories. Our first hour feels, to me, more in the realm of Kairos. It has tended to be more participatory and open-ended; time moves quickly; disciplinary boundaries are breached. The second half of our class is, by design, more “disciplinary.”

Our guest speaker, having not participated in our previous forum, brings his or her own visions and imaginings. Whether or not our first conversation has a natural ending point, we must begin our second, more bounded one.

[An aside on this also—can we ascribe meaning to the fact that our first set of readings has consisted, for the past two weeks, of a series of excerpts?

Our experience of engaging with texts, like that of the class, has involved an enforced stopping point that may or may not be a natural one. This is a thought I had, in fact, in the middle of our class “break”—something that itself might be worth further probing.]

What can we do in Academia when departments are structured through these times and themes?

Should the scholarship obey the Western dichotomy Kairos vs Chronos when in most of the non-Western cultures, time is conceived differently? Could we think about a Sufi experience of time in the scholarship?

[BH] What about Descola? And his four-section division of the relation to the self?

A half of the couplet dismembers itself. On to vibes.

A Bodily Experience in the class: the “vibes are good” or the “vibes are off”

We talked about SET and SCIENTIFIC vs AMORPHOUS and VIBESY.

Amidst speaking [BH] looked around the room and noted the “vibes were off.”

[CW] observed in her last summary a “vibes shift” between the first and second half of the class.

[MM] apologized in a comment tying [BH]’s comments in with our excerpts on experience for “bringing the vibe down” in addressing difference—as in Joan Scott’s “experience” excerpt.

Could these “vibes” and the “vibes” characterizing the umbrella under which “intellectual,” “erlebnis,” “kairos,” and “cosmology” fall be in anyway related? [DGB] mentioned some other fields where “vibes” ARE a THING. What about their EXPERIENCE in the class?

Should we feel good about vibing, or bad about vibing? Is the disciplinarity in the class supposed to make us vibe, or vibe differently? Sometimes in a class like that I feel that actually I should vibe, but oftentimes I also just vibe differently. Is vibing a question of intensity, preparation, knowledge, or understanding? Going with the flow is usually not one of the official definitions of academia. But if I am honest with you, it is one of its most common expressions.

Vibing questions the vibe: going with the vibe, on the vibe, over the vibe. Thinking?

In crafting this summary itself I feel I am indulging the impulse to grant terms more logic than they necessarily have—to conform with certain standards of what is Academic and what it takes to be a Professional Intellectual. I can see the form breaking down the further along I go in this. Historians write, almost exclusively, in the past tense.

Is that appropriate here?

–SD&CMP

SEMINAR 4: with Jeff Whetstone

[DGB starts here]

Just a few reflections on our session today — which both reviewed some territory across which we have moved in these first weeks, and also brought new views.

Some of the early conversation circled the semantic field of the word “protocol.” I won’t try to résumé this, but only underline how interesting I find the protocol as “form” (and we did a turn here into the idea of the “score” or the “action poem,” such as it found manifestation in the work of Fluxus artists, etc.). Protocol can also be a verb, it turns out — both transitive and intransitive. And the term certainly has something to do with norms and framing conventions. Discipline too? Surely. Also administralia and the world of diplomacy. Things to think about in all of this.

We did a loop out into questions of measurement, too. And the recursive/reflexive, as well as constitutive role of mensuration. This can be a metaphor, but also a highly material problem, too. And I mentioned Ken Alder’s The Measure of All Things, as a history of science and technology book I admire on these questions. Quantification and metrics have been a very important line of research in my own field, and the volume The Values of Precision was a field-shaping collection when I was just starting out as a junior scholar.

If there was an image I would like to hang onto from the first half of the session, it would be the little glyph on the board, above—which is meant to depict a table on the table. It reflects our meditation on the very notion of putting something “on the table,” a phrase to which we recur when hoping or intending to share, propose, wager, invite…well, what? Engagement? Consideration? Reflection? Something of all that. We dedided, I think, that we wanted to put putting things on the table…on the table. This felt like a potentially promising conceit/frame/query — perhaps even something that might prove thematically valuable as we continue to work our way toward collaborative final projects. What more could we do with this? Are there theorists who come to mind who have worked this question or its adjacencies? I am thinking. I am recalling a set of post-colonial theorists (folks like Paul Carter) who were interested in the inherent if sublated “violence” of the table — since it was on tables that the maps of empire were unrolled and marked up for possession and expropriation.

We should perhaps recall that to “table” a motion means (in parliamentary formalism) to place an issue aside for further discussion later. So “table” ends up having an oddly auto-antonymic register, as it is entangled with two very divergent meanings: to present to conversation, and to propose some deferral of that conversation. Odd!

Our conversation about the AAUP statement and the Butler rejoinder was compressed, but that created, for me anyway, a pleasing sense of pressure. I came away with a sense that the very idea of “criticality” with which Butler pushes back against the (not-perfectly-examined) positivism of the AAUP statement may not be entirely sufficient to the problem — or our moment. Criticality, too, can be bent to pragmatic effect. Defending the humanities in terms of “critical thinking” can feel like its own kind of instrumentalization. But that may just be me. We lofted the notion of “play” at this moment. And fretted as to whether it could ever feel like anything other than a dereliction of duty — a failure of seriousness. When the times are (always) serious.

Into that suspended question came Jeff Whetstone. And he offered a robust account of the essential significance of play. He showed us his…toy.

And took us into the incredible underworlds where he has been making his images. What did he say about the place of the artist in the university? Super interesting things. A few moments and phrases appear here:

Lots to say on all this, but for now, I will leave it with this amazing image—which depicts the actual costs of “making visible.”

Early atomist theories of vision mooted the notion that objects might throw off a kind of “skin” of themselves continuously, which the eye took in like a mouth, swallowing down the visibility of things. By these lights, opticality would gradually consume what came repeatedly into view. How uncanny, then, to see a kind of inversion of this in the work of the scanning electron microscope: that which is subjected to this gaze is literally “burned down” by that which is permitting it to be seen…

-DGB

[CW starts here.]

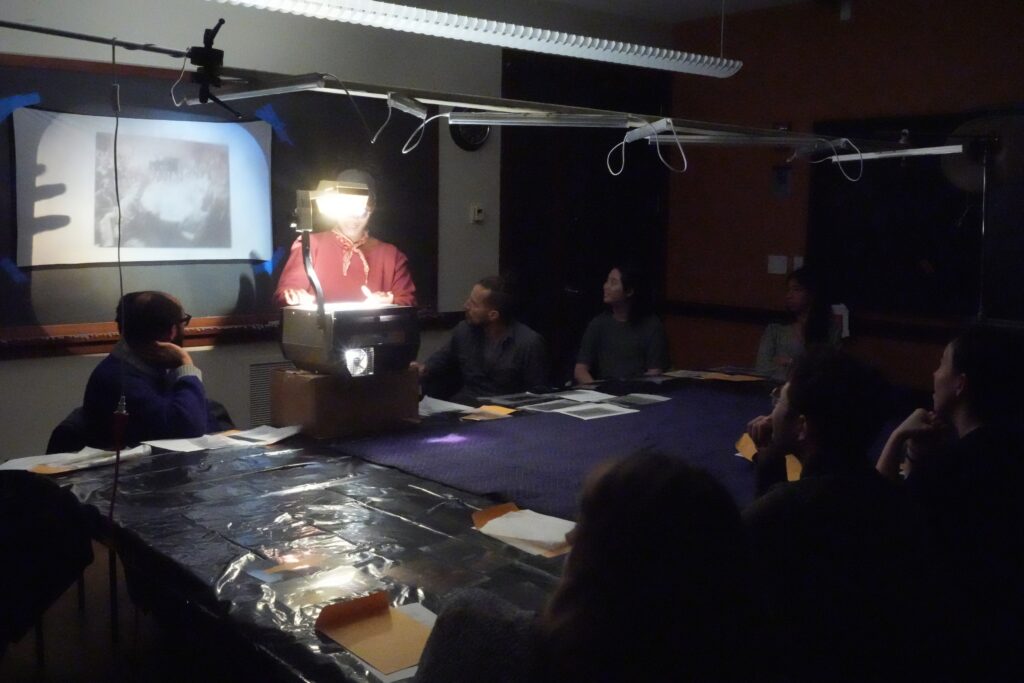

Working backward from JW’s visit, a few of us stayed around to see how the world looks through his 19th-century-looking camera – what I think might be called a tailboard camera, with bellows? It lends the world an eeriness more likely to be found in dreams than in waking life. That JW projected up the ablation sequences with the haunting soundtrack as a way to initiate the second part of class in the dark and that we spent some time with him in various cave systems certainly put us in a more ghostly headspace. In some ways, it generated a mood similar to that of JC and DX’s IHUM salon from last year, whose setting was a dimly lit space populated with self-animating objects and voices from the past.

That landscape is relative – that a microscopic object has its topology – was a wonderful direction for our thoughts to pursue. As JW showed beautifully, a landscape is never neutral. To make one, a photographer or painter has many choices to make, each of which is probably shaped by an explicit social or political position or by an unconscious one.

I wrote a thing last year about cave art and was so happy JW’s assigned reading and cave pictures let me revisit the Paleolithic underground. I liked DGB’s observation about the weirdness of Guthrie’s book as a scholarly object. While there are many books that straddle the university press/trade press divide, this one had a particularly hypothetical spirit and pretty wild form to it. I was curious about the author and found that he apparently invited friends to his home in 1984 “to eat stew crafted from a once-in-a-lifetime delicacy: the neck meat of an ancient, recently-discovered bison nicknamed Blue Babe.”

It seems like the table might end up having some presence in the final project. In the dark, I was thinking of Ouija boards, séances, and other practices of summoning that seem to require a table. Was thinking of the slippages there in a few different languages of the spirit/esprit/Geist/spirito/espíritu as mind but also as specter. Our bodies and the minds they contain are conjuring up thoughts together around the table. What might this have to do with other gatherings at other tables with other minds/souls/psyches/spirits working in unison?

Was also thinking about the continuity implied by ritual. That something might exist over time – a seminar that is repeated with its various protocols (or might we call them traditions?), a department, all of the university’s rituals – that preexisted and will continue to exist as various participants come and go, altering it sometimes in perceptible ways, other times leaving it fairly intact in its earlier shape. This is, of course, a thought partly set off by our own class. How does it change with each year with a new configuration of people? How is it different now that I am at DGB’s side? How was it when JD and DGB were team teaching? DGB solo? What about the combination of guests and the order in which they visited? The stuff they handed us to read, its relation to the world and contemporary circumstances? There is something fascinating to me about how all this happenstance can alter a thing – HUM 583 – that nonetheless remains itself from iteration to iteration.

Re: MM’s evocation of protocols, I was thinking how rarely I hear the word in a daily context except maybe in governmental or business settings? Maybe in relation to university admin but not in day-to-day life on campus. I dug around to see which synonyms might be more common and found a few that might be interesting for our continuing discussions (etiquette, conventions, formalities, customs, rules of conduct, procedure, ritual, code of behavior, accepted behavior, conventionalities, propriety, decorum, manners, courtesies, civilities, good form) and a few sort of weird funny ones (one’s Ps and Qs, the done thing, the thing to do, punctilio, politesse). In a statecraft setting, some synonyms include agreement, treaty, entente, concord, concordat, convention, deal, pact, contract, compact, settlement, arrangement, armistice, truce. Interesting how each of these has so much of its own baggage. One of the many simultaneous word clouds forming in the seminar.

A thing I wanted to throw on the table: The US News & World Report just released its annual rankings and Princeton is #1 again of all national universities, I think for the 14th consecutive year? What do you make of it? Just more food for thought at our plentiful buffet.

P.S. Thanks to AK for finding that Butler’s etymology of method (tracing back to the Methodists) was not quite right… Apparently, in English, it appeared in the medical field first. I thought that was a bit too perfect to be true.

-CW

[AT starts here]

Alright, it looks like it’s my time to bring my contribution to the table. This week’s seminar was an enriching one. The discussion of protocols felt fruitful. We spent some time thinking about what protocols do and why they’re important: they tend toward constraint and someone (I think MM, but I could be mistaken?) mentioned that one might be able to understand the structure of protocol as conditions of possibility for improvisation. In establishing a set of protocols, one enables the conditions of certain kinds of constraints. CW mentioned another word that has some resonances with protocol that I particularly liked—ritual. When a reoccurring event or a performance has protocols that we respect—for example, a seminar—it becomes ritualized. I started to wonder if thinking about protocols and rituals might encourage us to think a little more deeply on the importance of rituals and protocols in our disciplines. At a very basic level, I’m thinking of the protocols of academic writing when I say this: for instance, how do you work with a citation? (A question we raised at the beginning of the semester.)

JW came in and talked about his work, and the parallels between landscape painting and the photography he does was stimulating. As someone who knows very little about art history, and especially American art history, I liked his discussion of landscape painting from Breugel to Cy Twombly. It was exciting to get to understand the art he enjoys, his artistic trajectory, and how he got to the landscapes that he took photos of—fascinating and very exciting stuff! I especially appreciated the mention that the sample that he put under the microscope was something that “had to come from his own body,” and noticed my own gut reaction to it (cool and maybe a little gross). I liked hearing him talk about his process, and his remarks about art as a form of play resonated with me. I was struck by how frequently he called his camera and equipment “toys,” and we talked about this somewhat. If I remember correctly, his decision to call cameras toys was to highlight how he thought about the tools of his medium as being part of a poetical method as opposed to an analytical one. It complemented our prior discussion of constraints as a condition of possibility for improvisation nicely. “Generation” is a word that immediately comes to mind here; whereas I got the impression we were talking more about protocols in the university space before JW came, during his discussion we were broaching how the art object comes into being. Hearing him talk about artistic production as cultural and intellectual production only served to reinforce the theme of creation that felt so prevalent throughout the seminar. I also came away from the seminar thinking about how it felt important to meditate on the relationship between art objects and critique (which is what many of us produce) a bit more, and how we conceive of the relationship to primary sources and the archive, to which we refer so often, but it reminded me that it might be useful to spend some time really thinking through the circumstances of their production and how they relate to my own academic practice.

I’m going to start by talking about the end rather than the beginning, but what I found especially salient in JW’s talk was a word on which we more or less concluded: friction. I believe DGB mentioned it and I left our session wondering about how we handle friction as academics and, ultimately, makers of objects (textual, visual, musical, etc…), and found it a worthwhile question. I’m not going to venture a proper response, but will try to think about the various levels at which the question of friction is germane. I see it being relevant at the bounds that lie between one discipline and another; within a discipline, it can occur between competing, sometimes equally valid interpretations of an object; and even in terms of the media we use in the classroom. (The conversation started because of an offhand remark about how whiteboards don’t have the same sort of resistance as chalkboards do—I think JW said they weren’t as cool, which I agree with.) I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these conversations emerged as we talked about art as play, notably play as being only “a hair’s breadth from irresponsibility” (DGB). How do we make space for art and play in the university, especially when it can sometimes be dangerous or “irresponsible”? Does art introduce a kind of friction into the humanities that we need to learn how to live with? Where does that friction come from? I’m coming from a mostly literary background, where I work with various texts across a few languages, and have begun thinking about translation somewhat regularly as an area where friction arises. While I don’t think of myself as a translator in a professional sense, I’ve done occasional translation work, mostly but not exclusively from French to English, and one of the things I’ve realized in translating is that it is occasionally very difficult to find a word or phrase that captures all of the nuances of the original, and so something that I’d call friction emerges. How we tolerate discomfort—whether that be sensory/aesthetic discomfort or the unknown, more generally—seems to be a central question of art, and one lens through which we can think about what art is and can do. So, the question becomes for me: how do we, in the university, simultaneously hold space for discomfort and “mess” (I’ve been rewatching that Marie Kondo special that was popular when I was in college, and I like this word a lot) responsibly? I reflected on how space has become an important concern of mine during our seminars. For instance, I’ve been thinking of “the university” as “the university space,” very simply. I started to think about how spatial questions emerged for me when looking at the cave art that JW showed us: how do we mark our environment, and how does our environment bear traces of us? The cave art was insightful because it got me to start thinking about how we decorate spaces and what sort of significance that holds—there’s a whole cultural memory being created in the caves with the art painted inside of them. JW got me thinking about the identity of a place, in short. We could probably relate that more broadly to disciplines and disciplinarity and the space we occupy as academics in the university—what sorts of places do we want to occupy, and how do we see our role in them? How do they mark us as well, in a sense?

As you can tell, JW’s presentation raised a lot of questions for me, which is evidence of how exciting it was. What I came away wondering about was how practices of play can help us within our disciplines and potentially support us in pursuing work that extends beyond the reach of those disciplines. I don’t have answers at the moment, but I think the questions of play and how to tolerate discomfort/friction in the world are ones that come up for me. It was a great class and I’m looking forward to the next one.

-AT

[HH starts here]

We began with a discussion about “protocol”—from the unspoken expectations that structure the presentation of the weekly objects to the broader landscape of rules, regulations, norms, prescriptions, and disciplinary standards that organize and constrain our lives.

We spent some time discussing how we might go about defining “protocol” and many of us learned for the first time that it could be used as a verb. In this sense, “protocoling” seemed like another way to say “disciplining.”

Boundary drawing and positionality emerged naturally as complementary concepts, and from that—the question of whether measurement had anything to do with protocol. Insofar as protocols “call into being” our orientation to other people/things/institutions in the world, I think this jump to measurement made a lot of sense. “Measures” (n.) could conceivably be used in place of “protocols” to describe administrative procedures or processes, but it also brings to mind this idea of orientation, positionality, and perspective. With every observance of protocol we are submitting to our place in an administrative structure, abiding by a contract we didn’t know we signed but probably did? When we accepted our offer of admission at Princeton was there a clause about what constitutes “acceptable” speech or protest? I actually don’t know! Which also leads me to wonder whether, with every violation of protocol we are still—in acknowledging the transgression at all—submitting to our position in this structure.

There is also a spatial element to all of this—one “puts in place” measures or protocols. “Put on the table the ‘putting on the table’” came up a number of times. What gets said and what is considered worthy of a response? What gets put on board (and then immortalized on the website), what is permitted to just hang in the air, and what ends up floating above all of our heads?

At this point I thought back to Grossman’s Summa Lyrica and the idea of a “commonplace.” Are commonplaces protocols? They are, in some sense, rules or norms that structure our behaviors, conversations, and our general experience of being in the world. But there is, I think, an anonymity of authorship in the commonplaces that is not always present in protocol. University protocols might not have a name attached to them either, but there is not much ambiguity regarding their provenance or the institutional apparatus that produced them.

DGB also raised the example of Yoko Ono’s text Grapefruit and the collection of instructions (protocols?) it contains. One particularly silly piece I remember from her exhibit at the Tate Modern was “Carry a bag of peas. Leave a pea wherever you go.”

Some are more surreal: “Send the smell of the moon.”

And some more methodical:

Bandage any part of your body.

If people ask about it, make a story

and tell.

If people do not ask about it, draw

their attention to it and tell.

If people forget about it, remind

them of it and keep telling.

Do not talk about anything else.

(1962 Summer)

Are these protocols? Perhaps they are the opposite: surreal, illogical, intended to shift or disrupt your perspective—to undiscipline?

…

With the final 15 minutes of the first half of class, we briefly touched on the AAUP and Judith Butler pieces. The AAUP seemed to define (acceptable) knowledge in terms of its utility or pragmatic application, and above all of its generation under the strict observance of methods—or in other words: its adherence to protocol. To put it crudely, one should believe scientists—or more generally, “experts”—because they abide by a widely accepted and rigorously tested set of methods (protocols).

In a response to the AAUP, Butler asks what happens when method is broken? And what would it mean if this very act of breaking method were defined as a goal of education:

“What brings a discipline or field alive is precisely the moment when the metal on the instrument is wrecked and reformed by virtue of the obstinate character of its object, of what cannot be thought inside the prevailing frame. At such points, method is ruined, and critical thinking begins.”

The AAUP’s exaltation of “truth” ends up privileging a particular view of knowledge that suits some spheres of scientific inquiry but neglects the messier work of textual interpretation. Which is not to say that literary studies is without method. But perhaps it is the exercise of breaking and remaking method that is, as Butler suggests, the heart of critical thinking. Butler rejects the AAUP’s view of pedagogy as a simple transfer of Knowledge—“as a delivery vehicle to those seeking to gain expertise.” And here protocol returns when Butler asks, “Is pedagogy as delivery vehicle or transfer protocol really a fair and valuable way to think about what happens in the classroom…?”

I found myself ultimately sympathizing with Butler’s critique, though I know many of us saw good intentions in the AAUP piece. Perhaps the situation we find ourselves in is not, as Butler outlines it, a choice between critical thinking or the direct transfer of knowledge, but instead a much more dire question of whether these hypothetical humanities students will continue to exist? What will these internal debates about “truth” and criticality do to fill classrooms?

Part 2: JW’s visit

JW’s presentation brought some welcome texture and color to the room, and I wish I had more space to discuss it.

Without having heard our discussion about protocol, JW began with two points that I thought tied in rather nicely with our earlier conversation. Rather than “art practice,” JW preferred “play.” And instead of “apparatus,” “toy” would be the word of choice. Where practice, and to a greater extent apparatus, evoke the cold bureaucratic touch of “protocols,” play and toy feel just a tad more approachable (although we also discussed how toys often have their own protocols of play).