From Monica

In this week’s seminar, methodology was central to defining disciplines and interdisciplinarity, and addressing the “gaps” between disciplines. Erin Huang, working at the intersection or “gap” between East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature, talked about the experience of navigating different disciplinary expectations in her respective fields. Huang saw Comparative Literature as a type of European area studies that emerged as a utopian cosmopolitan project in Europe, whereas area studies, including East Asian Studies, emerged after WWII and is tied to U.S. military global surveillance projects. From these extremely different disciplinary histories, Huang situated herself as a crossroads in order to study the political theory of horror and its socio-political sentiments. What positioned her in the gap between these two disciplines was her need to redefine or expand definitions for existing concepts. The way she writes about “horror,” for example, falls outside of the traditional Euro-American genre that is recognized by Comparative Literature. Similarly, the way she talks about China, especially its connection to neoliberalism, falls outside of traditional modes of understanding China in East Asian Studies. She relied on a discipline outside of East Asian Studies to expand the definition of China and a discipline outside of Comparative Literature to expand the understanding of horror. In this sense, interdisciplinarity allows one to study what one wants without being confined to the boundaries of a discipline.

For Huang, this interdisciplinarity allowed her to create an entire genealogy that did not previously exist, such as that of neoliberalism in China. Neoliberalism, as she notes, commonly refers to American neoliberalism, which is an issue that perhaps has less to do with disciplinary boundaries and more to do with the imperialism of Euro-American academia more generally. Huang encourages us to really unpack terms like neoliberalism, which lack specificity and are used differently by different fields. We talked about the need to really articulate the gap between theory, text, and experience in negotiating the definitions for such terms and in negotiating the forms of power that control hegemonic definitions in the first place. Other examples Huang gave for these loosely defined terms in need of attention were: “cold war vs. post-cold war” (in order to question continuities and discontinuities in the language we use) and “colonialism vs. semi-colonialism” (to articulate the power of language in defining words like “colonialism” through colonial language).

Moreover, the question of language and expanding definitions for concepts like “neoliberalism” was brought up in relation to Classics as a discipline, and pre-modern, pre-capitalist studies more generally. Do these types of terms have a place in Classics? How do we use these terms without collapsing the gaps between fields? Huang noted this was a great example in terms of trying to articulate the gap, wherein pre-modern, pre-capitalist examples could bring new, exciting perspectives to existing languages and concepts. Furthermore, the tension between defining these concepts locally vs. globally is also important to keeping the concepts alive and meaningful in their usages. Considering the political pressures to stay inside the boundaries of a field, questioning disciplines based on their language and concepts seems like a daunting yet important “methodology” for interdisciplinary work and to expand the way we imagine modes of knowledge. At the end, Dolven left us with a related question: Can we consider method as fore-knowledge?

From Fedor

We began this week’s discussion by following up on Marshall Brown’s idea that urbanism can be called a “set of strongly held beliefs.” Ayluonne highlighted the tensions that exist between Brown’s formulation of urbanism and urbanism as a socio-historical paradigm, while Angelika pointed us to the tensions that lay distinctly around the borders between disciplines and the built/non-built environment. The class then moved to a broader discussion of Brown’s action-bias critique, and Brown’s distinct preference for framing projects as narratives rather than problems that require solutions.

Following the break, we were joined by professor Erin Y. Huang. Huang immediately pointed us towards her interest in methodology, especially as it intersects with her own disciplinary position in the university. Split between an East Asian Studies (75%) and a Comp Lit (25%) appointment, Huang narrated the ways in which these disciplines affect the methodological perspectives of her work. She addressed briefly the historical afterlives that disciplines hold — in relation to both Area Studies and Literary Studies — and how working between two disciplines with very different senses of historical perspective can open up certain theoretical “gaps” that she finds generative for her own scholarship.

Our discussion of productive disciplinary gaps continued to widen as we began a conversation about cross-cultural analysis. In discussing “neoliberalism” as a productive “Western” concept that, in Huang’s book, can be applied also to China, she fruitfully pointed us to the implicit tensions that arise between theory and geography. With a particularly productive question (“is Marx German?”) she was able to point us to the theoretical gaps that arise when theory is read from a global perspective or from a local one. She stressed the importance of not having to solve for either the local or the global: the tension between the theory and the source material can and should be productively explored in the interdisciplinary space, and it is the work of a responsible scholar to undertake that task.

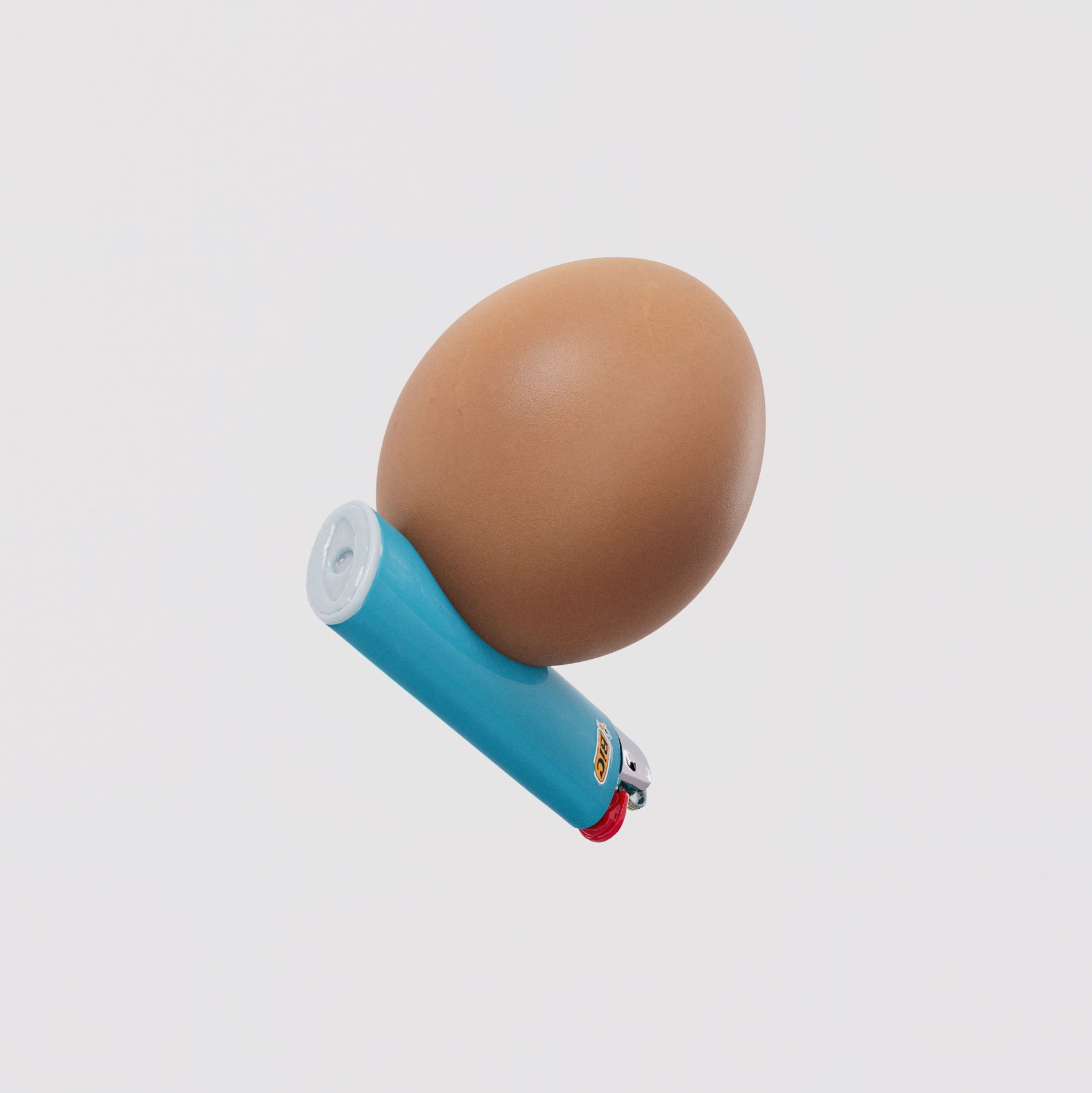

We finished the class with a discussion of the image, which Huang noted to be a particularly fraught topic in film studies. She concluded with a particular striking account of how her work always begins with the “technical materiality” of the image: a process that involves an unpacking of how the image was taken, how it circulated, what community it was from and who it was for — it is from this solid ground, Huang noted, that the the more theoretical work can begin.