In February of 1905, the inveterate animosity between Armenians and Azerbaijanis— then referred to as Tatars or Tartars— boiled over into an apocalyptic ethnic conflict now referred to as the Armenian-Tatar Massacres. Fillip Makharadze, a Georgian revolutionary and government official, describes it in Notes on the Revolutionary Movement in Transcaucasia: “The brutality knew no bounds. The streets were filled with the dead and wounded and with human blood. They did not distinguish between adults and children, women and men. They mercilessly killed everyone they met.” The violence between Armenians and Azerbaijanis more than a century ago has direct parallels to what we witness today. Over the past few decades, the two nations have battled fiercely over the Nagorno-Karabakh, culminating in the 2023 Azerbaijani offensive that resulted in a mass exodus of Armenians from the region. Allegations of ethnic cleansing and war crimes have been voiced as well. Though the exact circumstances and time period differ across the two, today’s conflict echoes the same themes of the 1905 Armenian-Tatar Massacres, one of the first major conflicts between the two ethnicities. As is the case with any modern conflict, understanding the history behind it is the first step toward achieving a lasting solution.

With regard to the causes, the violence of 1905 between Armenians and Azerbaijanis across the Caucasus was not only the result of the social and political atmosphere of the time, as will be explored, but also of the decades of enmity that preceded the outbreak. While both ethnicities evidently differ in language and religion, the source of the conflict extends further than cultural characteristics. The Swedish political scientist Svante Cornell, for example, notes in Small Nations and Great Powers that “in the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Baku oil boom led to a concentration of Armenians”’ who often held the managerial positions. In this way, he argues, they resembled the Jews in that both groups came “to dominate business life,” leading local populations to view them as “greedy, exploiting people.” Beyond the class and social-related causes, the Italian historian Luigi Villari, after visiting Baku in 1905, noted in his Fire and Sword in the Caucuses that “the Moslem community could not forget that the loss of their predominance was largely due to the Armenians” who welcomed Russian occupation and helped realize it, introducing a political reason for the tensions. In short, the Tatars viewed Armenians as culturally alien, invasive, and threatening, sentiments which ultimately led to the February massacres. In fact, the journalist James Dodd Henry makes this observation in his 1905 Baku: An Eventful History, writing that the Tatars justified their outbursts of fury as “their only weapon against being utterly destroyed by their competitors,” the Armenians.

On February 6, 1905, these tensions erupted into brutal massacres throughout the city, ending only with a clergy-brokered peace on February 9. After the February events in Baku, conflicts then spread throughout the region, reaching especially intense proportions in Shusha, a city approximately 230 miles west of Baku. Rumors of Armenian victories there proliferated in Baku, enraging and provoking the Tatar population to violence in late August and early September. As I will discuss, the starkest difference between the two waves of conflict lies in the government response. In February, as secondary literature has pointed out, the government responded to these four days of violence with marked inaction. Conversely, newspaper coverage of the August and September wave emphasizes “energetic” government action.

Among the secondary literature, there is discussion of government inaction in February. Makharadze, for instance, writes that the “the complete inaction of the authorities was confirmed by the government audit itself.” Cornell mirrors this, mentioning that the imperial authorities failed to intervene in the conflict. A third source, Dutch journalist Charles Van der Leeuw’s Storm Over the Caucuses, notes that “the Armenian bishop and the Azeri sheikh-ul-Islam, called on the people to calm down, and it was only then that Russian troops started patrolling the streets again.” That said, there is very little written about the government response in August and September and certainly no comparison of the approaches across both waves.

This gap in the scholarship of the Armenian-Tatar Massacres of 1905 in Baku begs the question: how does the government approach in February compare to that of the August- September massacres? And, if different, why is this the case? Herein, I will posit that there is a dramatic switch in approach observed in August and September, which is ultimately the result of two significant changes: 1) the higher degree of anti-Armenian sentiment among the governorship in February and 2) a self-serving desire to protect the oil industry in August-September. I will first begin by analyzing any observed differences between the government response using a variety of primary sources, eventually continuing to provide potential reasons behind the responses as suggested by newspapers.

Primary source material provides sufficient evidence to confirm the government’s inaction in February, especially Senator Alexander Kuzminsky’s report and Adjutant General Count Vorontsov-Dashkov’s 1907 The Most Humble Note on the Administration of the Caucasian Region. Kuzminsky, following his investigation, concludes that during one particularly instance of looting they “drove past without taking measures to disperse the crowd of Tatars” and, at other times, “crowds of armed Tatars, in the presence of many strangers, often police officials and Cossack patrols, destroyed and plundered.” He also announces that investigations found evidence that the Baku governor Prince Nakashidze, the police chiefs, and other officials had the opportunities and resources to both prevent and cease the massacres but instead allowed them to transpire. Meanwhile, Dashkov reflects, “Only by the totality of these hostile sentiments against Armenians is it possible to explain what happened in February, 1905, in the mountains. In Baku, for several days, Armenians and Tatars were massacred with almost complete inaction of local authorities, only partly justified by confusion due to the unexpectedness of the events.” In essence, it is evident that government officials did very little to prevent or resolve the conflict even though there was both opportunity and ability.

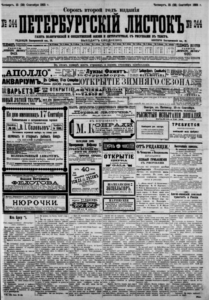

Newspapers, furthermore, verify the accusation of inaction. The Russkie Vedomosti, for example, reported the following under the “Telegrams” section on February 10: “Government and private institutions are closed in light of the Armenian-Tatar massacres. Murder and robbery are committed openly. Corpses lie uncollected.” Likewise, the Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii reported on February 14 that “murders and robberies by Tatars were committed openly throughout the whole city.” These two telegrams indicate that the massacres were widespread and openly committed, suggesting that police and military enforcement was severely lacking. In a more detailed account of the February massacres, the Peterburgskii Listok reprinted an article on February 16 from the Peterburgskie Vedomosti, which read:

It seemed there was no one to ask for protection. The police were literally absent; although after lunch, here and there on the streets, Cossack horse patrols appeared on the streets, and in the evening, even military soldiers. They were completely indifferent agents, not even trying to disarm the brutal criminals who hunted people like wild animals and killed them by the hundreds.

The article continues to describe how Tatars made use of their impunity to massacre and rob Armenians, containing more definitive proof of government inaction during the February massacres. In essence, the police were “absent” and the military units “indifferent,” simply allowing the grim events to unfold.

Secondary sources also imply that the government may have incited these attacks, but such claims are often left unsubstantiated. Makharadze, for example, points out the tensions between Armenians and Tatars before noting that the “authorities successfully took advantage of these differences between these two nationalities for their own purposes.” In Death and Exile, demographer Justin McCarthy writes that “by fostering (or at least doing nothing about) the antagonism between Armenians and Muslims, the Tsar ensured that they fought each other rather than united against his government.” In addition, Cornell writes that the government inaction “led to speculation that the authorities either provoked the violence or at least saw no reason to stop it, as it would distract both groups from their respective pursuit of freedom.” Hratch Dasnabedian, in History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaktsutiun 1890/1924 takes a stronger approach, accusing Nakashidze and other government officials of “inciting the Azeri mobs.” These sources and others seem to agree on the claim that the Russian government incited or at least encouraged the massacres, but they remain uncorroborated.

Primary sources, however, can resolve this issue of unverified accusations. As previously mentioned, the Russkie Vedomosti, Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii, and Peterburgskie Vedomosti all confirm that the government was almost entirely inactive during the conflict. They did not even attempt to pacify the angry, murderous mobs, suggesting that they were at least complacent. Beyond the newspapers, though, contemporaneous accounts of the events corroborate the claim that the government incited the mobs. Villari is one such source (an eyewitness, in fact). He recalls, “Excitement in the oil city and the hatred of the two races increased, and the Governor did nothing to reconcile them. On the contrary, he was perpetually talking of an Armeno-Tatar pogrom as imminent; he openly encouraged the Tartars, and treated the Armenians with marked coldness.” This testimony accuses the governor, Nakashidze, of encouraging the Tartars in their hate of Armenians while simultaneously referencing an inevitable pogrom. If true, this would undoubtedly constitute complicity. He continues, “The authorities were perpetually telling the Tartars that the Armenians were meditating a massacre of Mussulmans, and that they should be on the qui vive.” Here, once more, Villari postulates that the authorities told Tartars that Armenians were planning mass violence against them, thereby instilling a fear and hatred of Armenians and perhaps sowing the seeds for a proactive counter-massacre.

Another primary source, James’s above-referenced Baku: An Eventful History, which contains a journalistic investigation of the massacres in 1905, reports, “First of all the Tartars said they were attacked by Armenians, but, when the massacres were over, and the best and most influential of their class met the representatives of the Armenians, they declared that they were incited to use their revolvers and kinjals [sic.] by the authorities, who supplied many of them with rifles.” This fragment further supports the claim that the authorities provoked the Tatars, sparking the massacres in February. He also cites the Armenian claim that the police organized the procession of Tatars who carried the corpse of Babayev, a wealthy Tatar who was killed by Armenians, throughout Baku, which created much indignation among Tatar populations and eventually led to the outburst of violence in February. Villari concurs, stating that Nakashidze had reason to believe the procession would result in ethnic violence and could easily have prevented it. This proposes that the government’s complicity extended to enablement.

Their involvement, though, does not stop after the success of the incitement but continues during the massacres, as Kuzminsky establishes in his report. Therein, he contends that the Baku police often “entered into conversations with the armed Tatars, expressed sympathy for them, and showed some solidarity with them.” The effect of expressing sympathy and solidarity would have been, without a doubt, encouragement. A few pages later, Kuzminsky describes Nakashidze as “merciful and attentive with the Tatars,” continuing to say that “armed Tatars walked freely with him through the streets and often with weapons in their hands.” Not only did he walk amiably with the active Tatar participants in the massacre, but he also enabled them: “In some cases, the governor ordered the Cossacks to return confiscated weapons to some Tatars, with which they walked around the streets.” In short, Kuzminsky’s report corroborates Villari’s eyewitness description and Henry’s journalistic account of the government’s complicity in the massacres, furthering it with reports of encouragement and enablement.

Newspaper coverage in August and September, on the contrary, highlights a reactive and rather forceful government approach. At this point, critics may point out certain newspaper telegrams that indicate a lacking response to the violence. They may point to the Peterburgskii Listok’s August 28 edition, in which a telegram reads, “Local authorities, due to insufficient troops, are powerless to carry out the orders of the governor general.” Similarly, the Russkie Vedomosti reported on August 26 that, during the previous day, “It was reported from Baku that the troops in Balakhany and Bibi-Eibat are not able to protect the population.” On August 27, they reported under the telegraph news section that the February events were being repeated, including “the inaction of the administration.” Coverage along these lines would seem to suggest that the government was also inactive in the August reemergence, but in reality, they merely reference a powerlessness to respond as a result of an overwhelming resurgence in violence. Notice, also, that these reports are isolated to the beginning of the outbreak, before additional troops arrive later in August. Thus, the initial inaction differs from that of February because it was not intentional.

In fact, once reinforcements arrive from Tiflis, namely rifle and artillery battalions, they are immediately deployed to quell the riots, which three separate newspapers confirm. First, the Peterburgskii Listok reports on August 29 that, since the previous day, “energetic measures are being taken to suppress unrest.” Then, on September 12, they published a telegram from the previous day that notes, “Representatives reported to Count Vorontsov-Dashkov about the agreement and expressed deep gratitude to the count, who, with his charm and humanity, achieved successful results in establishing peace in the city.” After this, a story titled “Tatar and Armenian Meetings” started with the following: “Robberies and murders have subsided in the unfortunate, blood-soaked Baku. Thanks to strict, although also belated measures, relative peace was successfully restored.”

Second, the Russkie Vedomosti reported that troops intervened after a short firefight on August 29 with Tatar mobs. Then, they reported on August 26 that “all measures were taken by the military governor general for the cessation of riots.” The next day, they released another telegram from August 24, which read, “There is a fierce firefight with soldiers, among whom there are casualties.” The August 29 edition contained an excerpt from the Sankt-Peterburgskie Vedomosti, which briefly mentioned that “the Armenians are disarmed by the police” and a telegraph from General Shirinkin stating that “energetic measures are being taken for the suppression of unrest.” The adjective “energetic” repeats again on September 1, where the Russkie Vedomosti releases a similar telegram: “The governor general is taking energetic measures against those resorting to weapons.” Then, on September 2, another dispatch of troops was reported, this time the 3rd Caucasian Rifle Battalion. Even after the end of the Baku massacres, the government was still taking action, establishing preventative measures in the event of future ethnic violence. As an example of this, the September 11 edition describes a meeting with the governor general and senior war officials, summarizing, “It was decided to increase the number of troops, and to organize a military court for the judgment of crimes against life and property.” Then, on September 10, “60 intellectuals and workers were detained by police for an illegal gathering.”

Third, the August 28 edition of the Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii contained a telegram from Tiflis, which reads, “Artillery is being sent from here as well as from the Northern Caucasus.” A telegraph in the next day’s edition describes in detail the events of the conflict up until August 25. Among other bleak things, Christian workers had been surrounded by Tatar mobs and “measures are being taken by the governor general to defend them in Baku.” In short, surrounding areas sent military reinforcements, both rifle battalions and artillery, to Baku with the goal of ending the conflict. As the Peterburgskii Listok, Russkie Vedomosti, and Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii elucidate, these forces, under the direction of the governor general and other senior officials, took an active role in suppressing the violence during the August-September wave.

Up until this point, the discussion of the Armenian-Tatar Massacres of 1905 in Baku has been limited to the role of the government. In brief, I have reviewed the secondary literature on its role in the February outbreak, which accuses officials of idly observing and perhaps even inciting the massacres. This left two gaps, namely whether the accusations of idleness and incitement are factually founded and how said government action compares to their response during the August and September violence. I answered both, using eyewitness and journalistic accounts for this former and newspaper coverage from three different publications for the latter. I clarified that, in February, all evidence suggests government officials both failed to respond despite available opportunities and resources and also incited as well as actively encouraged the Tatar mobs. In the August-September wave, however, the government reacted strongly to the riots, using freshly arrived military units to “energetically” extinguish the conflict. Thus, the only outstanding information is the underlying reasons for the different approaches.

Firstly, during the February riots, there was far more pernicious anti-Armenian sentiment among government officials and local law enforcement. Prince Golitsyn, the Governor-General of the Caucasus until 1903, was one such government official who had a strong distaste for Armenians. As Villari characterizes him, “he was destined to be the arch-enemy of the Armenian people.” He closed down Armenian schools, forced Armenians out of the public service, intensified censorship of the Armenian press, and applauded the 1903 seizure of the Armenian Church’s property. Villari suggests that he was, in part, motivated by a desire to “Russify” the Armenians, leading to his “peculiar personal antipathy against the Armenians.” Among all of the anti-Armenian actions during this era, the most effectual was M. von Plehve’s seizure of Church property, which effectively led to the popularization of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). In 1903, radicalized Armenians attempted to assassinate him, seriously wounding him yet amplifying his hatred to such an extent that he declared, “In a short time there will be no Armenians left in the Caucasus, save a few specimens for the museum.” Though he left in 1904, Villari notes that he left Prince Nakashidze, the governor of Baku, behind “to continue his Armeno-phobe policy; its natural outcome was the Baku outbreak in February, 1905.” Henry, furthermore, assents that Golitsyn, “remembering the attempt on his life and anxious for revenge, pressed on Prince Michael Nakashidze, the Governor of Baku, the necessity for the adoption of strong measures.” The anti-Armenian sentiment, though, pervaded all levels of government, extending beyond Nakashidze to minor officials and the police, who Villari names “Golitsyn’s creatures.” In essence, in February there existed strong anti-Armenian sentiment that could be traced from minor officials all the way to the governorship, fueling hatred and motivating the massacres.

Secondly, given the ongoing First Russian Revolution, Russian authorities feared the perdition of the empire at the hands of revolutionaries like the ARF. Therefore, it was in the interest of the government, as several other scholars also note, to allow the Caucuses to become so embroiled in their ethnic conflicts that they, at least for the moment, abandoned their aspirations of national sovereignty. Why specifically a conflict targeting the Armenians? As Makharadze illuminates, the Armenians had “generally much more revolutionary elements among the Armenians than among the Turks.” In summary, the increased radicalization of Armenians caused by attempts to “Russify” them in conjunction with the government’s ongoing battle against a strengthening revolution incentivized the Russian authorities to observe and perhaps instigate the ethnic conflict between the two nationalities.

Though there were certainly traces of anti-Armenian sentiment in August and September, an ARF member assassinated Prince Nakashidze, removing one of the most anti-Armenian officials in the Caucuses from power. More importantly, however, the August-September massacres presented a new challenge which overshadowed whatever perceived incentives there may have otherwise been. This challenge was the annihilation of the oil industry. While the February massacres were primarily located within Baku, those in August-September were most intense on the outskirts of Baku, particularly near the oil fields of Bibi-Eibat and Balakhany. In a series of articles written by a Peterburgskii Listok correspondent, he describes Baku as the city of “burning oil” and “soaked in blood.” He contrasts the relative indifference of those in Moscow and Saint Petersburg to the conflict with the fervor of the oil industrialists, who telegraphed frequently and begged refugees from Baku for any information. The correspondent describes what he witnesses as he approaches Baku by train. He sees a “column of black smoke,” the “burning of industries,” flames flashing on the horizon, and a total “rage of fire and blood.” Balakhany is burning and Bibi-Eibat’s fate: the same. The Peterburgskii Listok continued to report equally bleak news regarding the destruction of the oil industry. On August 27, a telegram states, “Arson and theft in the fields continues,” the next day bore news that “workers from the burned fields are leaving Baku by the masses,” and as of the September 10, “according to the mining supervision, 1,176 towers were burned, and according to industrialists, 2,000 out of 3,500 were.” Similar themes of burning oil fields and the mass exodus of workers appear in the Russkie Vedomosti. The August 26 edition contains much of this information, noting that on August 24th, oil industrialists received word that all of the Balakhany, Sabunchi, Romantsickaya, and Bibi-Eibat fields were burning. Telegrams also conveyed that the “losses of the oil industrialists are colossal,” amounting to an estimated “hundreds of millions of losses” in the Balakhany fields alone. Overall, according to Henry’s account, output of the five major oil fields in the Baku region was reduced from 735,036 tons to 296,218, and out of 1,609 wells, 1,026 had been destroyed. As the news under the “By Telephone” section of the August 28 edition states:

The repositories of all industrial life have died out; all employees and workers are in a state of panicked fear, leaving the fields to the mercy of fate, and are gripped by the horror of these terrible events which have led to the complete destruction of the multimillion-dollar property and equipment of the entire Baku oil industry, which generates over 100 million rubles in annual income and also supplies, fuel, and light for almost all of Russia.

This excerpt displays the significance of the Baku oil industry, describing it as a major center of oil production and income generation for the Russian Empire, while also illuminating the gravity of the events taking place in Baku. It is therefore evident that, since the oil industry was now being targeted during the August-September outbreaks, there was immense incentive to swiftly put an end to Armenian-Tatar conflicts, hence the strong government response.

To summarize, secondary sources note remarkable government inaction during the February outbreak in Baku of the Armenian-Tatar Massacres, making unsubstantiated claims that the government provoked the Tatars to violence. A review of primary sources, including accounts from Villari and Henry, newspapers, and Senator Kuzminsky’s official report, indicates that the government was not only inactive but also likely encouraged and incited the massacres. Analysis of newspapers during the second wave in August and September, however, depicts a much different government response, one involving artillery fire and “energetic” action on the part of military authorities. In particular, the Peterburgskii Listok, Russkie Vedomosti, and Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii report that government officials were very involved in suppressing the crimes of murderous, arsonist mobs. Not only do they elucidate notable differences in government responses, but they also provide a glimpse into the reasoning underlying the reversed approach. While the government had motivation (i.e. anti-Armenian sentiment, distracting revolutionaries with ethnic conflict) to encourage the February riots, the targeting and colossal destruction of the Baku oil industry in August and September had the opposite effect, demonstrating that ethnic violence can be leveraged as a political tool but often spreads like an uncontrollable wildfire.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Henry, James Dodd. Baku: An Eventful History. London: Archibald Constable & Co., 1905. https://archive.org/details/cu31924028739088.

Kuzminsky, Alexander Mikhailovich. Всеподданнейший отчет о произведенной в 1905 году, по высочайшему повелению, сенатором Кузминским ревизии города Баку и Бакинской губернии [The most humble report on the audit of the city of Baku and the Baku province carried out in 1905, by the highest order, by Senator Kuzminsky]. Saint Petersburg, circa 1905. http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/65967-kuzminskiy-a-m-vsepoddanneyshiy-otchet-o-proizvedennoy-v-1905-godu-po-vysochayshemu-poveleniyu-senatorom-kuzminskim-revizii-goroda-baku-i-bakinskoy-gubernii-spb-190.

Villari, Luigi. Fire and Sword in the Caucuses. London: T. Fisher Unwin Adelphi Terraci, 1906.

Vorontsov-Dashkov, Illarion. Всеподданнейшая записка по управлению Кавказским краем генерал-адъютанта графа Воронцова-Дашкова [The most humble note on the management of the Caucasus region by Adjutant General Count Vorontsov-Dashkov]. Saint Petersburg: государство, 1907. http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/36390-vorontsov-dashkov-i-i-vsepoddanneyshaya-zapiska-po-upravleniyu-kavkazskim-kraem-general-adyutanta-grafa-vorontsova-dashkova-spb-1907.

Вестник Маньчжурских армий [Vestnik Manchzhurskii Armii (Herald of the Manchurian Armies)]. Yeoman/Liaoyang, 1904-1906. http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/86742.

Петербургский листок [Peterburgskii Listok (Petersburg Leaflet)]. Saint Petersburg, 1877-1918. https://gpa.eastview.com/crl/irn/newspapers/leaf.

Русские ведомости [Russkie Vedomosti (Russian Gazette)]. Moscow, 1863-1917. http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/18938-russkie-vedomosti-moskva-1863-1917-ezhedn.

Secondary Sources:

Cornell, Svante. Small Nations and Great Powers: A study of ethnopolitical conflict in the Caucuses. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

Dasnabedian, Hratch. History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaktsutiun 1890/1924. Milan: Grafiche Editoriali Ambrosiane, 1990.

Makharadze, Filipp. Очерки революционного движения в закавказьи [Essays on the Revolutionary Movement in Transcaucasia]. Georgia: Госиздат грузии, 1927.

McCarthy, Justin. Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims 1821-1922. Princeton: The Darwin Press, 1995.

Van der Leeuw, Charles. Storm Over the Caucuses: In The Wake of Independence. U.K.: Curzon Caucasus World, 1999.