Scientists, Degenerates, Martyrs:

The Images of the Woman Nihilist in Russia and the West

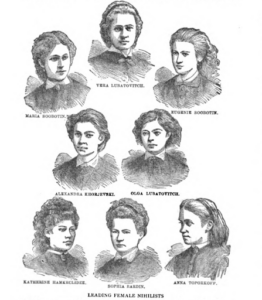

An engraving from J.W. Buels’. Russian nihilism and exile life in Siberia. A graphic and chronological history of Russiaś bloody Nemesis, and a description of exile life in all its true but horrifying phases, being the results of a tour through Russia and Siberia: p. 177.

In the Russian Empire of the 1860s, a revolutionary and social reform movement often referred to as the “Nihilist movement” came to prominence, composed mostly of disillusioned university students and young elites skeptical of the Russian monarchy and the imposed social and political norms. However, despite the failure of the Nihilist movement to inspire an overthrow of regime, the Nihilist movement helped characterize the latter half of nineteenth century Imperial Russia as a time of upheaval, with the birth of socialist and reformist ideas that will create the foundations for later, more successful revolutions. This Nihilist upheaval manifested in more radical actions: political terror and violence—the various attempted and successful political assassinations—but also in changing understandings of government, “the West” and as this paper will notably explore—gender.

Women were well documented participants in the Nihilist movement, from Vera Zasulich to Sophie Perovskaya, however, recordings and documentation of these women by both Russian and “Western” authors and reporters impose the image of the female Nihilist with their own political motivations, with the female nihilist becoming a romantic archetype in the West, while anti-nihilist Russian literature often criticized and caricaturized the political role of women in the 60s and 70s. I am interested in questioning how different sources create a character or archetype of the female nihilist, and what these perspectives reveal about interpretations of Russian nihilism and the role of women and gender.

Thus, in this paper, I will examine the varying depictions of female nihilists in the Western press reacting to the nihilist movement in the 1880s, as well as American journalist J.W. Buel’s travel account Russian nihilism and exile life in Siberia, alongside Fyodor Dostoevsky’s condemnation of the nihilists—the novel Demons, contemplating how these depictions form an understanding of the role of gender in political movements and in the media throughout and across the borders of the Russian Empire. First, I will attempt to clarify a definition of the Russian nihilist movement, before moving to the interpretation of female nihilists by Russian and foreign sources.

Some misconceptions link Russian nihilists solely to anarchists, political extremists, and assassins, however the actual practices and political ideologies of the young nihilists varied greatly, and did not exist as a great organized movement with universally solidified goals. In establishing a clear-cut definition and delineation of the Russian nihilist movement, I look to Richard Stites’ examination of Russian nihilism in his work The Women’s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilsm, and Bolshevism, 1860-1930. Here, Stites writes that “nihilism was not so much a corpus of formal beliefs and programs (like populism, liberalism, Marxism) as it was a cluster of attitudes and social values and a set of behavioral affects—manners, dress, friendship patterns. In short, it was an ethos.” In this way, Russian Nihilism, rather than in a Nietzschean sense or as a political ideology, can be understood as a social movement among young elites and university students, acting as a response and a form of rebellion to issues that were relevant in Imperial Russian society of the 1860s—the impoverishment of peasants, the instability and oppression of the monarchy, and shifting considerations of class and gender, with the hope of greater democratization and liberalization is society.

The female nihilist, the nigilistka, was thus an observable social archetype—the upper class woman who has rejected the traditional role of the elegant, gowned aristocratic woman who serves as a wife, mother and a polite member of tsarist society. Instead, “the archetypical girl of the nihilist persuasion in the 1860’s wore a plain dark woolen dress, which fell straight and loose from the waist with white cuffs and collar as the only embellishments. The hair was cut short and worn straight, and the wearer frequently assumed dark glasses.” This social change was framed by changing educational opportunities for upper class women—the chance to peruse academia, the sciences and higher education rather than a more traditional path. During the early 1860s, universities across Russia, including the St. Petersburg Medical-Surgical university allowed women to attend lectures, with some even bestowing degrees to their female students. However, after social unrest following Alexander II’s Emancipation of serfdom, the monarchy turned to more conservative public policy, accumulating in the ending of many university programs for women in 1865. After these limitations, many Russian women pursued educational opportunities abroad in Switzerland and other European countries, where they became some of the first women to receive doctoral degrees in “medicine, chemistry, mathematics and biology.” To this, Ann Hibner Koblitz observes:

“Many of the nihilist women were full of idealism about the West and about the level of democracy and equality they assumed Western Europe to have achieved. They felt inferior, coming as they did from “backward” Russia, and they confidently expected to be joining the ranks of numerous European women already engaged in serious study. To the Russian women’s astonishment, they discovered that their ideas and attitudes, their eagerness for education, and their determination to succeed in spite of obstacles in some respects put them in the forefront of the European women’s movement”

In this way, the Russian women in European academia represented notable feminist achievements towards greater opportunities for women beyond traditional sectors, and, like the young Russian men also studying outside of Russia, the women who chose to return to Russia afterwards brought with them new knowledge of both their field, and of European styles of government and philosophy that advocated for social reforms and more democratic styles of government.

Furthermore, many intended to use their education and specialties for sociopolitical goals and change: “Sofya Kovalevskaya had at first intended to become a doctor for political exiles in Siberia and had planned to study her beloved mathematics only in her spare time. The revolutionary Vera Figner wrote that she and her comrades had learned medicine and the sciences in Zurich ‘in order to have in our hands weapons for social activism.’” However, this combination of a foreign education and reformist hopes for Russian social change inspired greater protest and criticism from the monarchist government and press.

In 1866, the Manchester Guardian published a translated article, which was originally published in the St. Petersburg Northern Post, described as the “official organ of the Russian Ministry of Internal affairs.” This article was a response to the attempted assassination of Tsar Alexander II by Dimitri Karakozov, in which the St. Petersburg newspaper writes:

“During [Karakozov’s] stay in Moscow he became a member of a secret society, chiefly composed of students and young men attending the lectures of the agricultural and other institutions of that capital… with the aim to spread socialistic doctrines, to destroy the principles of public morality, shake religious belief and ultimately overthrow the state by revolutionary means…Many of the young men travelling abroad to complete their education entered into relations with the agents of revolutionary societies, and returned, infected with socialist principles, communicated the poison to our youth.”

Thus, we can see the changing values of the young Russian elites who were educated outside of the country, as well as the Government’s fear and criticism that this phenomenon would “poison” society and cause violent “overthrow.” Though Karakozov and the young people “travelling abroad to complete their education” described in the article are now often referred to as Nihilists, the characterization of the social movement among young, educated aristocrats as Nihilists did not emerge until the years after Ivan Turgenev popularized the term for the generational divide and differing social values in the younger population as “nihilism” in his 1862 novel Fathers and Children [Otcy i deti].

Russian authors in the 1860s and 70s also responded to the wave of nihilism among the younger populations in their works, often with criticism, as reflected by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolai Leskov, Ivan Goncharov and as we will examine in this paper, Fyodor Dostoevsky, showing the reach of the sociocultural movement within Russia. Dostoevsky’s Demons (sometimes also titled The Possessed in English) paints a grim perspective on young nihilists, telling the story of a group of student revolutionaries, led by a young aristocrat, who imagine themselves to be a cell in a massive structure of groups, organizing a conspiracy to overthrow the oppressive monarchy. In reality however, the political groups are fractured, and there is no unity or organization of ideology that would allow for group action, and their plans descend to chaos and baseless violence, ending in the cold blooded murder of one of the members, a plotline inspired by the murder of a student by the revolutionary group of Sergey Nechayev in 1869, which was widely covered by the media, and shocked and horrified its audiences.

Dostoevsky characterizes the nihilist through scenes of mental and moral degradation, offering a criticism of the misguided and violent political motivations of the young people, who mindlessly follow others and use cruelty and chaos to achieve social change rather than compassion. But we can also look to Dostoevsky’s Demons for an image of female nihilists (nigilistki) at the time. Dostoevsky, like many of his contemporary anti-nihilist authors, was critical of the progressive view of femininity that the younger generation presented, as well as their rejection of traditional religious and cultural roles. Thus, in Demons, Dostoevsky creates a caricature of the female nihilist that highlights a sense of sexual immorality, shameless and crude rejection of convention, and general frivolousness. The character, Madame Virginsky, holds meetings for the other young nihilists in her home, where they discuss political and social matters. Dostoevsky describes her in the following manner:

Madame Virginsky was a midwife by profession—and by that very fact was on the lowest rung of the social ladder, lower even than the priest’s wife in spite of her husband’s rank as an officer. But she was conspicuously lacking in the humility befitting her position. And after her very stupid and unpardonably open liaison on principle with Captain Lebyadkin, a notorious rogue, even the most indulgent of our ladies turned away from her with marked contempt…But though she was a nihilist, Madame Virginsky did not, when occasion arose, disdain social or even old-fashioned superstitions and customs if they could be of any advantage to herself.

Madame Virginsky, though a prominent member of the nihilist revolutionary group in the novel, receives “contempt” from regular society because of her sexual relationships, rude personality and self-serving nature—a biting representation of the female nihilist which condemns her on moral grounds. In this way, Russian literature of the late 19th century, represented and criticized nihilist women for being corrupted by progressive ideals and lifestyles.

To this idea, Goncharov, speaking on the corruption of young women, wrote “isn’t it a fact that women disregarded their loved ones, were seduced away from respectable life, society, and family by the crude heroes of the ‘new force,’ the ‘new course’ and by the idea of some sort of ‘great future’?” He thus blames the male nihilists, the “crude heroes” and the external forces and Western ideologies for influencing the female population and drawing them away from a proper and “respectable” path. This of course, is not to say that these authors did not also create female characters who were intelligent, respected and capable—they most certainty did—however, they did not view nihilist women in this same positive light, extending to them the same moral criticism of their nihilist identity that they extended to their male counterparts.

However, on the other hand, the Western press became enamored with the vision of the female nihilist as a political martyr and a virtuous and persecuted rebel to Russian authoritarianism. Ironically, while Russian media coverage represented the nigilistki as being morally corrupted or deficient, the Western media heaped praise upon the idea of the Nihilist woman as almost saint-like in morality and values. This fascination was sparked primarily by the assassination of Alexander II in 1881, as waves of commentary and speculation swept through Europe about Russia’s sociopolitical state of present and future, and interest in those involved in political resistance against the tsar rose.

From this media coverage emerged an archetype of the Russian Nihilist woman as a romanticized parallel to the despotism of the tsar—a woman who is beautiful, and pure and passionately fights against the injustice of the antiquated and backward Russian government. These depictions of nigilistki provide insight into standards of femininity and womanhood within Western Europe as well, as Sandra Pujals writes, that from this Western European perspective: “Women’s nature and the best characteristics that identified her sex – passion, virtue, and selfless surrender – also defined the female Russian revolutionary, except that in the case of the nihilist, intense emotions were saved for the cause and not for a husband.”

The coverage of Nihilist women in European media included many melodramatic literary elements—depictions of suffering and martyrdom at the hands of the government, melodramatic descriptions of the bravery and danger of the women, and subtle erotic undertones towards the passionate and foreign women. We see this phenomenon in a 1879 article by the Chicago Daily Tribune, which provides a sensationalized praise of nigilistki:

The feminine police spy was usually an abject, abandoned adventuress, ready to employ her personal charms to lure men into traps where the police could pounce down upon them; but the woman who belong to the Nihilists, so far as they have been discovered, have proved to be pure, virtuous, devoted, and self-sacrificing…ready to share all the dangers of the new war upon absolutism, and contributing to the cause by their keen intuition, and delicate intentions, and personal bravery as much as men.

The article emphasizes the contributions of women to their political movement, but also, rather than describing the feats of specific women, creates a sweeping and generalized portrayal of the women of the movement. Furthermore, this work demonstrates the European perception that incorrectly equates Russian nihilism as an organized, unified and planned movement against the monarchy, which it notably was not.

Alongside depictions of nihilist women, Western press was also fascinated with portrayals of Russian Siberia, and at times, of the women who were sentenced or chose to selflessly follow their husbands to prisons and labor camps there. In the essay “‘A Nihilist Kurort’: Siberian Exile in the Victorian Imagination, c.1830–1890” Ben Phillips examines the foundations of the European stereotype of Siberia as a vast and snowy wasteland, full of suffering, horror and prison camps. Phillips notes that these images arise from tendencies towards Orientalist depictions of Russia, “showing how the construction of these geographical ‘others’ as backward despotisms underpinned the image of an enlightened or democratic West.”

Furthermore, the individuals in Western accounts of Siberia reflect a dramatized trend of the martyrdom of Russian political rebel, where the hero “becomes not only emblematic of the revolutionary struggle against tsarism, but a projection of the modern Western self.” And the Russian heroine arguably functions in the same way, but in a more eroticized manner. The Nigilistka portrayed in Western media represents all of the romanticized “Western” values—the conflict against tyranny, agency, and self-determinism, but with the exterior of a beautiful and desirable woman.

In this vein, in 1883, the American travel writer and journalist J.W. Buel published an account of his journey through Russian Siberia, and the people, customs and traditions that he witnessed there. In his chronicle, titled Russian nihilism and exile life in Siberia. A graphic and chronological history of Russiaś bloody Nemesis, and a description of exile life in all its true but horrifying phases, being the results of a tour through Russia and Siberia, Buel describes his goals for the project as the following:

They have focused the interest of the world, until to-day the Czar’s dominions have become a country so alien in all its aspects of civilization, and rent internally by such horrible atrocities, that its current history is a story replete with exciting situations and horrifying culminations. To obtain a true conception of Russia’s policy, of her insubordinate elements, of the Nihilistic demonstrations, of her administration in dealing with the revolutionists, and lastly, of the exile life led by so many thousand persons in Siberia, I personally visited that country under auspices peculiarly favorable for the acquisition of information I specially desired.

His descriptions of Russia as an “alien” country solidifies our understanding of Buel’s Western biases and perspective towards Russia, which he uses to write a sensationalist and orientalist journalistic account of Siberia, not as an academic study of the region, but as a sort of adventure tale that will appeal to his American audience.

In Chapter IX Buel writes about “female heroism” and “leading female nihilists,” focusing on the various women that he meets in Siberia. Writing of prisoners, sentenced to time a prison he visited, Buel recounts:

The Soobotin and Lubatovitch sisters were ladies of many accomplishments and noted also for their beauty and purity, yet they stimulated their male collaborers by many acts of cunning and recklessness. The two former acted as spies, and actually secured from a leading officer all the immediate plans of Gen. Ignatieff for overcoming Nihilism.

Including an engraved image of the sisters and other Nihilist women at the beginning of the chapter, the physical appearance of the women, and the way in which they can be seductive and appealing to a male audience is Buel’s primary motivation in his portrayal of the sisters. However, an important characteristic of the women is their persecution—they are imprisoned and thus martyred for their actions by the monarchy in the eyes of their Western audience. Once again, Buel shows the Western tendency to equate Nihilism with a sort of planned revolution against the Tsar that the women have gathered together to conquer, creating an oppositional narrative of Nihilism versus the Tsar.

Thus we have found three differing depictions of the nigilistka: the first being the young aristocratic woman who rejects prior social conventions to pursue more progressive opportunities for women—often a Western higher education, with the goal of a career in medicine or the sciences. A second image emerges from anti-nihilist literature of the 1860s and 70s, which offers a moral criticism of nihilism at large as a misguided and ineffectively reformist, and the woman who have been led astray by the sociocultural changes of the younger generation. The Western media creates a third image of the heroine martyr woman, a figure of symbolic opposition to the backwards Russian monarchy. Ultimately, due to the expansiveness of Russian nihilism in the 1860s, ranging from individual political revolutionary groups, to youth interest in Western philosophy and education, to merely new trends in how women dress and represent themselves in society, we see that the female nihilist can have many facets, becoming varying social archetypes that emerge out of the media sources that remember and represent them, and observing these archetypes can inform perceptions of gender and female empowerment in Russia and the broader West.

Bibliography

Primary sources:

Buel, James W. 1883. Russian nihilism and exile life in Siberia. A graphic and chronological history of Russiaś bloody Nemesis, and a description of exile life in all its true but horrifying phases, being the results of a tour through Russia and Siberia. Chicago, Ill: A.G. Nettleton & Co. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89054373055

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. Demons. Translated by Constance Garnett. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc, 2017.

“A RUSSIAN CONSPIRACY.” The Manchester Guardian (1828-1900), Aug 24, 1866. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/russian-conspiracy/docview/474562431/se-2.

“THE WOMEN NIHILISTS.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922), Apr 27, 1879. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/women-nihilists/docview/172024905/se-2.

Secondary sources:

Howe, Irving. “Dostoevsky: The Politics of Salvation.” The Kenyon Review 17, no. 1 (1955): 42–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4333540.

Koblitz, Ann Hibner. “Science, Women, and the Russian Intelligentsia: The Generation of the 1860s.” Isis 79, no. 2 (1988): 208–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/233605.

McNeal, Robert H. “Women in the Russian Radical Movement.” Journal of Social History 5, no. 2 (1971): 143–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3786408.

Phillips, Ben. “‘A Nihilist Kurort’: Siberian Exile in the Victorian Imagination, c.1830–1890.” The Slavonic and East European Review 97, no. 3 (2019): 471–500. https://doi.org/10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.97.3.0471.

Pozefsky, Peter C. “Reviewed Work: The Odd Man Karakozov: Imperial Russia, Modernity, and the Birth of Terrorism by Claudia Verhoeven”. The Journal of Modern History 83, no. 4 (2011): 968–70. https://doi.org/10.1086/662354.

Pujals, Sandra. “Too Ugly To Be a Harlot: Bourgeois Ideals of Gender and Nation, and the Construction of Russian Nihilism in Spain’s Fin de Siècle.” Canadian-American Slavic studies = Revue canadienne-américaine d’études slaves. 46, no. 3 (2012): 289–310.

Sizemskaya, Irina N. (2018) Russian Nihilism in Ivan S. Turgenev’s Literary and Philosophical Investigations,Russian Studies in Philosophy, 56:5, 394-404, DOI: 10.1080/10611967.2018.1506011

Stites, Richard, The Women’s Liberation Movement In Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860-1930. New ed. with afterword. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991.