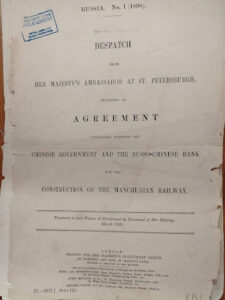

Russia. No. 1 (1898). Despatch from Her Majesty’s ambassador at St. Petersburgh, inclosing an agreement concluded between the Chinese government and the Russo-Chinese Bank for the construction of the Manchurian railway. (1898). Command Papers, 105. 19th Century House of Commons Sessional Papers. https://parlipapers-proquest-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/parlipapers/docview/t70.d75.1898-076577?accountid=13314

The Russo-Chinese Bank has been described as the “greatest Tsarist financial institution operating not merely in China, but in the whole Far East” (Quested, 1977, p. 1). Through the Russo-Chinese bank, Russia succeeded in securing a railway concession through China’s territory, connecting Chita with Vladivostok via Manchuria. This was not merely an infrastructure project, but led to northern Manchuria essentially becoming a Russian outpost, occupied by Russian personnel.

Sergei Witte has been credited with a number of landmark reforms in Russia during his time as Minister of Finance, including introducing the gold standard. His memoirs detail the establishment of the Russo-Chinese Bank and the Chinese Eastern Railway Company, as well as the Li-Lobanov treaty that made it possible. This paper focuses on the period following 1895. Russia had little capital and no banking ecosystem comparable to France, Germany and Belgium. At the same time, “the policies pursued by the Russian government in the nineties resembled closely those of the bank in Central Europe” (Gerschenkron, 1951, p. 20).

What was Russia’s purpose in creating the Russo-Chinese bank? How did Russia use banks as an agent of imperialist policy?

The prominence of the Russo-Chinese bank suggests that Russia was not hampered in achieving its economic goals despite lacking its own capital. Given the close connection of the Bank with the Chinese Eastern Railway Company, it also seems, at first glance, that the economic and political goals of Russia were inseparable.

My primary sources include Witte’s memoirs, which Witte finished in 1912 and were published in translation in 1921, and a British dispatch detailing the agreement between the Chinese government and the Russo-Chinese Bank, as well as a small number of news articles from the time. My secondary sources include Romanov’s “Russia in Manchuria” (1952), Quested’s “The Russo-Chinese Bank: A Multinational Financial Base of Tsarism in China” (1977), Crisp’s “The Russo-Chinese Bank: An Episode in Franco-Russian Relations” (1974), Lukoyanov’s “Русско-Китайский банк в 1895–1904 гг.” (2008) and Yago’s “The Russo-Chinese Bank (1896–1910): An International Bank in Russia and Asia” (2012).

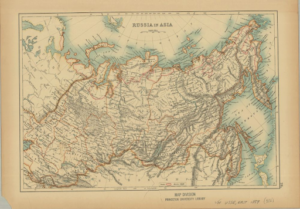

Bartholomew, J. (1889). Russia in Asia. Edinburgh: Published by A. & C. Black.

The Russo-Chinese Bank

Following the Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895, with China having lost the Sino-Japanese war, Witte details in his memoirs how he orchestrated for China to pay Japan indemnity, rather than for Japan to annex parts of southern China. It was in “Russia’s best interests”, Witte writes, “[…] that no power be allowed to increase its territorial possessions at China’s expense” (Witte, 1921, p. 83). The Foreign Minister, Prince Lobanov, arranged for the support of France and Germany, which has since been called the Triple Intervention. Witte argues that Lobanov “knew no more about the Far East than the average school boy” (p. 82). In doing so, Witte attempts to establish his authority in matters relating to the Far East, calling himself the only Russian statesman who “was familiar with the economic and political situation in that region” (p. 82). The Liaodong peninsula, which Japan had occupied, was thus returned to China. Witte therefore prevented another power from expanding their territory in the Far East.

In order to help China pay the indemnity, a French-Russian loan syndicate was organised. Romanov (1952, p. 65) describes that the indemnity involved paying around 280 million roubles to Japan over the course of seven years, therefore necessitating a loan to China. Crisp (1974) details how the loan syndication was not Witte’s idea and St Petersburg was not involved in the initial negotiations between the French, German and English banks (Romanov, 1952, p. 65). In fact, it was the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas who invited Witte to be part of the international loan syndicate for the issue of a loan to China (Crisp, 1974, p. 197), believing it would interest Russia “from the political angle” (Romanov, 1952, p. 65). Russia would participate in the “administration of Chinese debt” but the loan consisted fully of French capital. Although Witte, from his own account, was crucial in arranging the indemnity, Russia was not a key player in the initial idea for the loan. This is interesting given the later railway concessions that were effectively granted to Russia. By inviting Russia, France gave Russia the needed foothold in the Far East, especially with the provision of French capital.

Subsequently, Witte details how the Russo-Chinese bank was established by himself to help French financiers in their activities in China, given that they had helped Witte with providing capital for the loan to China (Witte, 1921, p. 85). Romanov offers an account from a different angle: on the day the loan to China was signed, Witte proposed the establishment of a bank whose purpose was “to operate, in the broadest terms, in the lands of eastern Asia” (Romanov, 1952, p. 68). Crisp notes that Witte saw the additional task of the bank as “strengthen[ing] Russian economic influence in China as a counter-weight [to Britain]” (p. 198). It was incorporated on 10 December 1895 (Crisp, 1974). The bank was afforded various rights: “trade, transport of commodities, conduct of any operational services for the Chinese treasury […]” and most importantly, the right to undertake “acquisition of concessions to build railways anywhere within the confines of China” (Romanov, 1952, p. 68). The enshrinement of acquiring railway concessions in the Bank’s initial rights makes Witte’s assertion that the Bank’s purpose was to support French activities all the more questionable.

The capital was sourced mainly from French and Belgian banks, who provided five eights of the initial six million roubles (Quested, 1977, p. 3). The rest was sourced from German-Jewish banks. Gradually, however, French control over the bank declined.

On Witte’s insistence, the board of the directors of the bank was composed of five Russians and three Frenchmen. Additionally, Prince Ukhtomski was the President, having been nominated by the Russian government, but he was merely a “figurehead” (Quested, 1977, p. 6). The first managing director was A. Yu. Rothstein (Quested, 1977, p. 6), who was another German in the service of the Russians. The French directors included Noetzlin and Hottinguer. Yago (2012) notes how the French position was further weakened given the separation of finance and government on the French side – the French bankers were not fully aligned with the interests of the French government. This misalignment did not exist with Russia, who had no independent, powerful banks. Despite this initial imbalance, Crisp (1974) details how the French believed that they would play a leading role in the bank, given it was formed mainly through French capital.

Once concerns were raised regarding the composition of the board of the directors and the name of the bank (“the Russo-Chinese bank”) which excluded French interest, it was too late (Crisp, 1974). In 1897, the Russian Ministry of Finance bought an additional 6,000 shares from the French investors (Quested, 1977, p. 6). In 1898, an agreement was reached for the Russo-Chinese bank to collaborate with the Bank of Indo-China (Crisp, 1974, p. 207), which was a French bank whose purpose was to finance French development of Asian colonies. This was another reactionary response on behalf of the French government to regain control over the activities of the bank. Shortly after, the Russo-Chinese bank issued 12,000 new shares, all of which were acquired by the State Bank of Russia, therefore giving Russia a majority.

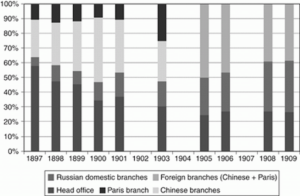

Yago (2012) concludes: “At least from 1898 on, the governance of the Russo-Chinese Bank was dominated by the Russian interests, and the Bank came to be a Russian international bank instead of a French one.” Russia therefore succeeded in reducing French control of the bank, despite the fact that it was comprised mostly of French capital. This, combined with the fact that Russia had no independent banking sector, effectively placed the bank into the hands of the Russian Empire, despite having little capital of its own. The reduction in French control can be seen by the shift in capital away from being held in the Paris branch. Over the 1897-1909 period, the bank decreased its assets held in the Paris branch (see Figure 1). Not only did the location of capital shift, but the bank also grew. In 1901, the bank had 31 branches and 10 agencies (Quested, 1977, p. 33). Between 1901-1904, 13 new branches were added, bringing the total to 45 (Lukoyanov, 2008, p. 179).

However, Crisp (1974) argues the clash that the Russo-Chinese bank embodied was in fact not that of Russian and French interests, but rather between the French government, who desired to have active control over the policy of the Bank, and the French financiers, who were happier with reaping profits from their business activities in China. This misalignment did not exist in Russia, who, as Witte recognises, had no developed banking ecosystem. On the one hand, while this forced Russia to rely on foreign capital for financing, it also meant that it had its in arsenal financial means to further the imperial agenda. Regarding the implementation of the vodka monopoly in Russia in 1893, an inspector of the French financial department noted presciently that “only an absolute monarch of an unusually firm character could carry out such a measure in France” (Witte, 1921, p. 57). Witte agrees, because in France “it would be detrimental to the interests of too many moneyed people” (p. 57). Just as with the vodka trade, Russia had no separation between finance and government. This aided it in assuming control of the Russo-Chinese bank by pushing out French interests. Therefore, counterintuitively, it was to France’s political detriment that its banking ecosystem was developed and could act independently of the French government.

Lukoyanov notes that by 1897 “банк становился в политическом смысле инструментом для защиты исключительно российских интересов.” (Lukoyanov, 2008 p. 172).

Bartholomew, J. (1889). Russia in Asia. Edinburgh: Published by A. & C. Black.

The Chinese Eastern Railway Company

“The idea that the laying of the Siberian railway through Chinese territory beyond Baikal was one of Russia’s urgent needs arose in 1895 out of the Sino-Japanese war situation, quite empirically.” (Romanov, 1952, p. 62)

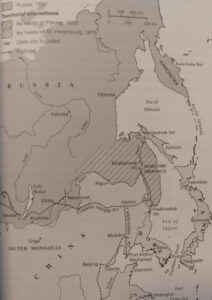

The following details the formation of the Chinese Eastern Railway Company, whose purpose was to build a connecting railroad in Manchuria for the Trans-Siberian railway. This is what Romanov calls the period of “peaceful” penetration into Manchuria (Romanov, 1952, p. 62).

In March 1898, Britain’s ambassador to Russia sent a dispatch to London detailing the contents of the agreement between the Chinese Government and the Russo-Chinese bank (Figure 2). It describes the formation of the Chinese Eastern Railway company, whose purpose is the “construction and working of a railway within the confines of China”. It notes that the Company has been given rights to “exploit other enterprises in China”, including “mining, industrial and commercial.” It gives the Company ownership of the railway for eighty years. In the event of a “difference of opinion” arising between the Siberian Railway and the Chinese Eastern Railway, the Russian Minister of Finance will have the final say – that is, at the time, Sergei Witte.

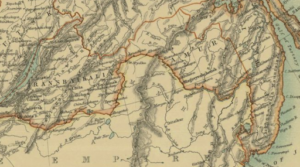

The geographical necessity of building through China can be seen starkly when examining a map of the region (Figure 3). Witte takes credit for the idea of “building the road straight across Chinese territory” (Witte, 1921, p. 86). He refers to the economic reasons for this – it would considerably shorten the line. “The Manchurian route would save 514 versts” (548 kilometres) (Witte, 1921, p. 86). He wanted to “gain China’s permission for this plan, by peaceful means based on mutual commercial interests” (Witte, 1921, p. 86). He emphasises again that “under no circumstance was the Trans-Siberian to serve as a means for territorial expansion.” (p. 87).

If we are tempted to attribute our distrust to post-facto knowledge of what followed, one of Witte’s contemporaries raised an immediate objection. Witte was not in fact the only Russian statesman familiar with the Far East. The Director of the Asiatic Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Count Kapnist, wrote of the “enormous political risk” that Witte’s plan involved (Romanov, 1952, p. 73) and argued that it would be “impossible without military occupation”. He was a proponent of the shorter line to Blagoveshchensk, instead of cutting across horizontally to Vladivostok. Both lines were approved.

While the placing of the railway through Chinese territory made economic sense, the need for a railway in the first place is not as immediately obvious. In his memoirs, Witte describes how “the idea of connecting European Russia with Vladivostok by rail was one of the most cherished dreams of Alexander III” (Witte, 1921, p. 52). The railway could be viewed as both a symbol of unity, bridging the Asian and European characters of Russia, and also an expression of civilisation, imposing modern engineering on the wilderness of the east. However, Witte’s romantic presentation of the railway masks political and military goals behind its expansion eastward. Witte repeats again that “it must be borne in mind that the great originator of the Trans-Siberian had no political or military designs in connection with the road. It was an enterprise of a purely economic nature” (Witte, 1921, p. 85). In fact, Witte complained that the Ministry of War was often his enemy, attempting to place railroads in such a way as to aid military endeavours, only to find them useless two or three years later (Witte, 1921, p. 75). By juxtapositioning himself as the rational economist attempting to improve Russian productivity against war-inclined ministers, he furthers the idea that he had no political or military reasons for the railroad. He explicitly rejects the notion that the railroad, and therefore the Russo-Chinese Bank that funded it, was a tool of imperialist expansion. Witte also takes great pains to impress that the railroad was fully supported by both Alexander III and his son, Nicholas II. To what extent the railroad expansion was indeed fully driven by the Tsar’s wishes is questionable, though Witte gives ample evidence in support of this.

The origins of the Chinese Eastern Railway Company must be examined to understand what role the Russo-Chinese Bank played in Russia’s interests in the Far East.

Following China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese war, the Chinese statesman Li Hung-chang arrived in St Petersburg in April 1896. Witte describes how Prince Ukhtomski met him at the Suez Canal and ensured he went straight to Odessa (Witte, 1921, p. 87) and then to St Petersburg, rather than visiting any other European countries. This was, it must be noted, in the context of negotiations taking place in Peking. Romanov details the various machinations of Americans, British and Russians in Peking to secure various concessions from the defeated Chinese, who were literally and symbolically in debt to Europe.

Witte employed several tactics to push his railroad agenda with Li Hung-chang. Firstly, he reminded Li Hung-chang of Russia’s assistance in creating a loan syndicate to help China pay indemnity to Japan (Witte, 1921, p. 89). Secondly, despite himself rejecting military reasons for railroad expansion, Witte employed military reasoning when attempting to strike a deal with China (Witte, 1921, p. 89). Witte details in his memoirs that he impressed upon Li Hung-chang that in order to assist China militarily against Japan, a railroad was necessary, so that troops could move quickly to China. Throughout, he reminds Li Hung Chang that Russia is adhering to the “principle of China’s territorial integrity” (Witte, 1921, p. 89). Romanov’s account paints a less sympathetic picture: specifically, the promise of a three million rouble bribe to Li Hung-chang, two million of which never materialised (Romanov, 1952, p. 85). It is likely that Witte’s portrayal of the negotiations lacks the intimidation and cajoling that actually took place. Similarly, Li Hung-chang would have been placed in a very awkward position had he not accepted Ukhtomski’s offer to go to Odessa with him, despite his probably pre-planned itinerary.

Romanov details how Witte first aimed to obtain the railway concession in the Russian government’s name directly (Romanov, 1952, p. 82), rather than through the Russo-Chinese bank. Li Hung-chang refused this proposal. Witte was successful in obtaining a concession in the name of the Russo-Chinese bank instead. It is probable that Witte was actually not successful in securing everything he wanted: Romanov (1952, p. 79) describes that the second demand the Chinese government anticipated from Russia was access to a warm water port, which did not materialise as a result of these negotiations.

In his memoirs, Witte details the three provisions of the agreement, the first being:

“The Chinese Empire grants us permission to build a railroad within its territory along a straight line between Chita and Vladivostok, but the road must be in the hands of a private corporation…” (Witte, 1921, p. 90, emphasis added)

The other two gave Russia the right to have its own police on the strip of land where the railroad was to be built and obliged Russia and China to defend each other in the case of a Japanese attack. Witte admits that the terms of the agreement were skewed towards Russia (p. 95), particularly given that China could buy the road only in thirty-six years but it would need to pay the Chinese Eastern Railway Company at least 700 million roubles. Otherwise, it would receive the road in eighty years. Romanov details how Witte wanted to ensure that China would not get the road in 36 years (Romanov, 1952, p. 89); hence the prohibitively high sum.

These concessions were part of secret Li-Lobanov Treaty. It has since been considered one of the series of unequal treaties which China was forced into signing following their defeat in the Sino-Japanese war.

However, the idea that the Russian government did not own the railroad was merely a “fiction” (Romanov, 1952, p. 85). The bank was not an autonomous financial institution but merely the tool of the empire. Romanov details how the concession became “virtually at the Russian government’s disposal” (Romanov, 1952, p. 86). Firstly, the Russo-Chinese bank bought all 1,000 of the Company’s shares, at a price of 5,000 roubles each. Secondly, those shares were transferred from the Russo-Chinese bank to the State Bank of Russia, through a loan without interest from the State Bank to the Russo-Chinese bank. There was a small possibility of placing some of these shares with French banks, but this did not materialise (Romanov, 1952, p. 87). Therefore, the State Bank of Russia became the sole owner of the Chinese Eastern Railway Company. However, the Company now had 5,000,000 roubles from the State Bank. Witte decided that the Company owed the State Bank for the surveys in Manchuria they had conducted before commencing construction. These surveys were authorised by the Chinese government while negotiations were taking place. The value of the surveys was put at 4,000,000 roubles and therefore 4,000,000 roubles reverted back to the Russian government (Romanov, 1952, p. 88). Therefore, the Russo-Chinese bank still had the concession with the Chinese government, but craftywas controlled by Russian interests despite being founded with French capital. The Chinese Eastern Railway Company which would construct and operate the railroad, while technically a private enterprise, was effectively owned by the Russian government. The right to the concession and the right to operate and construct both within the Russian government’s control. Significantly, the Chinese Eastern Railway Company had right to the “lands necessary for the construction, exploitation and protection of the line”, as well as “an absolute and exclusive administrative right” (Romanov, 1952, p. 91). During the Boxer uprising in 1900, when the Chinese Eastern Railway portion of the Trans-Siberian line was damaged, Russia was given the excuse to send troops in Manchuria.

Evtuhov, C., & Stites, R. (2004). A History of Russia. Cengage Learning.

Discussions regarding Romanov

Beloff reviewed the translation of Romanov’s book by the American Council of Learned Societies and noted that it was missing the original summary, which involved the key sentence: “It teaches the great lesson that the alliance between Finance and Government always jeopardises the peace of the world for the private gain of a few of the nationals of a Government enthralled by the International Capital.” Beloff himself was a Jewish-Russian emigre whose family left Russia in 1903. He also focuses on the Publisher’s Note, which criticises Romanov’s work for not including the “class struggle underlying tsarist Russia’s whole imperialistic policy”. Published in 1928, this inclusion of this note suggests that Romanov’s account of Russian banking did not suffer from Soviet historical revisionism, therefore necessitating a strong objection in the beginning from the publishers. However, Beloff argues Romanov was motivated by the need to “discredit” the overly-sympathetic portrayal of Witte’s Far East policies in his own memoirs. This suggests caution with interpreting Romanov’s account of Witte, especially with his highly critical portrayals.

A more favourable review of Romanov’s work appeared in the The American Slavic and East European Review. Whiting congratulates Romanov on a work of “scholarly objectivity”, though again noting the hostility to Witte. Whiting notes that what seems to be missing is an analysis of the motivation behind Russia’s penetration into North China and Korea.

Conclusion

It cannot be denied that Witte understood the importance of foreign capital. He calls out his detractors, who mistakenly thought that Russian infrastructure should be built with Russian money. “They overlooked the fact that the amount of available capital in Russia was very small.” (Witte, 1921, p. 74). Russia was under-developed compared to other European nations and had no comparable banks, as there was no little capital (Gerschenkron, 1951). Through this reasoning, Witte is attempting to make credible the “fiction” of the Russo-Chinese bank. It suggests that the Bank was the creation of an economist, rather than an imperial expansionist, in order to realise an economically-sound project. However, if the railroad was only an economic endeavour, as Witte portrays it, there would have been no need to reduce French control in the Russo-Chinese Bank or for the State Bank of Russia to buy all shares of the Chinese Eastern Railway Company.

It is clear, that in the period following 1896, the Russo-Chinese bank was a facade. It could be argued that perhaps the bank initially served the interests of French investors, who wanted to further their activities in China, and therefore somewhat fulfilled the raison d’etre of a bank (to be an intermediary between borrowers and lenders).

The fact that the Chinese Eastern Railway Company was created by the Russo-Chinese bank is a political gimmick. With regards to the portion of the Trans-Siberian Railway between Chita and Vladivostok, Russo-Chinese bank itself was a stand-in for the State Bank of Russia, arising out of negotiations by Li Hung-chang and Witte. Similarly, the fact that a private company built the railroad does not mean that it was a capitalist enterprise arising out of market need. Rather, it was state-directed.

The absence of capital and independent Russian banks in the 1890s allowed Witte to create such institutions to serve political purposes, rather than financial purposes that they served in France or Germany. Furthermore, under the guise of a private enterprise, the Russo-Chinese bank was able to enter into an agreement with the Chinese government to create the Chinese Eastern Railway Company, which extended the Trans-Siberian Railway into China’s Manchurian territory.

The Russo-Chinese Bank (1896–1910): An International Bank in Russia and Asia in The Origins of International Banking in Asia: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199646326.003.0007

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bartholomew, J. (1889). Russia in Asia. Edinburgh: Published by A. & C. Black.

Russia. No. 1 (1898). Despatch from Her Majesty’s ambassador at St. Petersburgh, inclosing an agreement concluded between the Chinese government and the Russo-Chinese Bank for the construction of the Manchurian railway. (1898). Command Papers, 105. 19th Century House of Commons Sessional Papers. https://parlipapers-proquest-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/parlipapers/docview/t70.d75.1898-076577?accountid=13314

THE REPORTED RUSSO-CHINESE TREATY: THE MANCHURIAN RAILWAY. (1896). Guardian News & Media Limited. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/historical-newspapers/reported-russo-chinese-treaty/docview/483541195/se-2?accountid=13314

Witte, S. (1921). The Memoirs of Count Witte (A. Yarmolinsky, Trans.). Doubleday, Page & Company. (Original work published 1921)

Secondary Sources

Beloff, M. (1954). Review of Russia in Manchuria (1892-1906). Pacific Affairs, 27(4), 386–386. https://doi.org/10.2307/2753085

Crisp, O. (1974). The Russo-Chinese Bank: An Episode in Franco-Russian Relations. The Slavonic and East European Review, 52(127), 197–212. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4206867

Evtuhov, C., & Stites, R. (2004). A History of Russia. Cengage Learning.

Gerschenkron, A. (1962). Economic Backwardness in historical perspective. Cambridge, Mass. The Belknap Pr. Of Harvard Univ. Pr.

Lukoyanov, I. V. (2008). Russo-Chinese Bank in 1895-1904. In “Keep up with the powers…” Russia in the Far East at the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries. https://histrf.ru/uploads/media/default/0001/09/45e4c8877870c2a0be8da582a7dc52d0fbf5dc2d.pdf

Quested, R. (1977). The Russo-Chinese Bank. Department of Russian Language & Literature University of Birmingham.

Romanov, B. A. (1952). Russia in Manchuria, 1892-1906, [Rossiya V Manchzhurii] by B. A. Romanov. Translated from the Russian by Susan Wilbur Jones. J. W. Edwards.

Whiting, A. (1954). Russia in Manchuria (1892-1906). The American Slavic and East European Review, 13(2), 280–280. https://doi.org/10.2307/2492074

Yago, K. (2012). The Russo-Chinese Bank (1896–1910): An International Bank in Russia and Asia. Oxford University Press EBooks, 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199646326.003.0007